Wall Street speculators are zeroing in on the next U.S. credit crisis: the mall.

It’s no secret many mall complexes have been struggling for years as Americans do more of their shopping online. But now, they’re catching the eye of hedge-fund types who think some may soon buckle under their debts, much the way many homeowners did nearly a decade ago.

Like the run-up to the housing debacle, a small but growing group of firms are positioning to profit from a collapse that could spur a wave of defaults. Their target: securities backed not by subprime mortgages, but by loans taken out by beleaguered mall and shopping center operators. With bad news piling up for anchor chains like Macy’s and J.C. Penney, bearish bets against commercial mortgage-backed securities are growing.

In recent weeks, firms such as Alder Hill Management — an outfit started by protégés of hedge-fund billionaire David Tepper — have ramped up wagers against the bonds, which have held up far better than the shares of beaten-down retailers. By one measure, short positions on two of the riskiest slices of CMBS surged to $5.3 billion last month — a 50 percent jump from a year ago.

“Loss severities on mall loans have been meaningfully higher than other areas,” said Michael Yannell, the head of research at Gapstow Capital Partners, which invests in hedge funds that specialize in structured credit.

Nobody is suggesting there’s a bubble brewing in retail-backed mortgages that is anywhere as big as subprime home loans, or that the scope of the potential fallout is comparable. After all, the bearish bets are just a tiny fraction of the $365 billion CMBS market. And there’s also no guarantee the positions, which can be costly to maintain, will pay off any time soon. Many malls may continue to limp along, earning just enough from tenants to pay their loans.

But more and more, bears are convinced the inevitable death of retail will lead to big losses as defaults start piling up.

The trade itself is similar to those that Michael Burry and Steve Eisman made against the housing market before the financial crisis, made famous by the book and movie “The Big Short.” Often called credit protection, buyers of the contracts are paid for CMBS losses that occur when malls and shopping centers fall behind on their loans. In return, they pay monthly premiums to the seller (usually a bank) as long as they hold the position.

This year, traders bought a net $985 million contracts that target the two riskiest types of CMBS, according to the Depository Trust & Clearing Corp. That’s more than five times the purchases in the prior three months.

Dying Malls

Sold in 2012, the mortgage bonds have a higher concentration of loans to regional malls and shopping centers than similar securities issued since the financial crisis. And because of the way CMBS are structured, the BBB- and BB rated notes are the first to suffer losses when underlying loans go belly up.

“These malls are dying, and we see very limited prospect of a turnaround in performance,” according to a January report from Alder Hill, which began shorting the securities. “We expect 2017 to be a tipping point.”

Category: Financial Markets

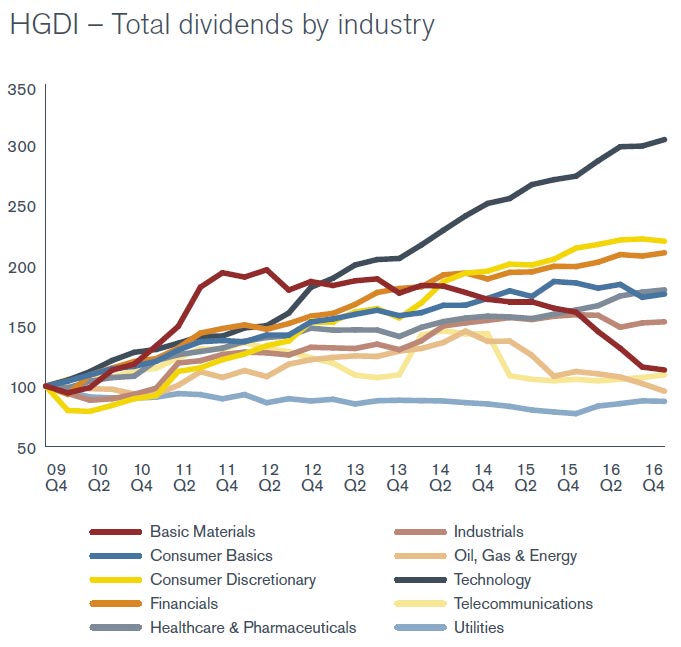

Banks Account for Half of the Australia’s Total Dividends

The Henderson Global Dividend Index found that total dividend payouts across all geographies rose a little – by 0.1 per cent – to reach US$1.154 trillion in 2016, reflecting flat profits. They are predicting a headline growth rate of 0.3 per cent in 2017 with global dividends forecast to reach US$1.158 trillion. The index covers the world’s largest 1,200 firms, representing 90% of global dividends paid.

Strongest sectors were utilities, healthcare and technology, weakest were energy and mining sectors. Finance contributed 23 per cent of the total paid.

In Australia total dividends were US$41.8 billion, down 10.1 per cent on 2015. They say Australian dividends are more reliant on the payouts from just a few large stocks than any other developed country and is the largest payer in Asia Pacific excluding Japan, making up almost two-fifths of the total.

In Australia total dividends were US$41.8 billion, down 10.1 per cent on 2015. They say Australian dividends are more reliant on the payouts from just a few large stocks than any other developed country and is the largest payer in Asia Pacific excluding Japan, making up almost two-fifths of the total.

The report says declines in the mining sector inflicted the most damage, with dividend payouts down US$4.5 billion year-on-year. After adjusting for a slightly stronger Australian dollar, the underlying fall from the total market was 12.2 per cent. This included big dividend cuts from Woolworths and Woodside Petroleum.

But their next comment is important:

Together the banks account for half of the country’s total dividends, while CBA alone is responsible for $1 in every $5 distributed.

CBA was the 12th largest dividend payer in the world, with HSBC in 6th place in the rankings. These are the two highest placed finance sector companies.

Think about the implications of this given the talk about corporate tax cuts. Much of the benefit will flow to a small number of larger companies, and many of these have high numbers of overseas investors. So the flow of “stimulation” into the local economy is likely to be very small.

The North American dividend payments of US$443.7 billion grew at 0.5 per cent because of a series of special dividends and index changes, though underlying growth was 3.9 per cent. The USA accounted for two-fifths of global payouts.

The possible impact of the Brexit on the financial landscape

Dr Andreas Dombret Member of the Executive Board of the Deutsche Bundesbank spoke about the potential impact of the Brexit on the financial sector.

Let’s start with the potential impact of the Brexit on the financial landscape. First and foremost, this means talking about market access. We should not forget that this is a two-way street, and so I will talk about market access in both directions. But the centre of attention is certainly on market access for UK based financial institutions to the EU, as this potentially has the largest impact for banks and other financial institutions. It affects all institutions, both from the UK and the rest of the world, which currently use London as a hub for their continental European business.

The debate on market access was transformed in mid-January. Prime Minister May made it clear that the UK is looking for a clean break from the EU’s single market. For the financial industry, this means that the current model of using London as a gateway to Europe is likely to end. Banks from third countries need a licensed entity inside the European Economic Area to gain access to the whole area, known as “passporting”. Shortly before the Prime Minister’s speech, CityUK already dropped demands for maintaining access through passports.

Instead, many are now hoping for an equivalence decision to fill the gap left by passporting rights. If the European Commission deems the regulatory and supervisory regime in the UK to be equivalent to that in the EU, market access would be partly retained. However, I am rather sceptical about whether equivalence decisions – may they be likely or not – offer a sound footing for long-term location decisions of banks. Equivalence is truly different from single market access.

There are three major drawbacks to equivalence decisions. First, they only cover the wholesale business of banks. Second, given the fact that banks need time to build up a new entity elsewhere, an equivalence decision would have to be taken quite soon to actually have a bearing on the location decisions of banks. Third, equivalence decisions are reversible, so banks would be forced to adjust to a new environment in the event that supervisory frameworks are no longer deemed equivalent. These drawbacks lead me to the overall conclusion that equivalence decisions are not a reliable substitute for passporting.

So it seems that the prospects for EU market access through the UK look rather dim. To ease the pressure on financial institutions, a transition period could help. It would reduce risks and increase planning security for banks, which would be economically beneficial. Furthermore, it could support a smooth relocation process by taking pressure off both supervisors and banks, for example by making

“first mover advantages”less important. This being said, transition periods would be a politically sensitive topic in the negotiations, and it is unclear how likely such an agreement might be.As mentioned earlier, we should not forget about the access of European banks to the UK, which is also an important issue. For German banks, for example, the UK is the second-most important foreign market, right after the US. It will be up to the UK Prudential Regulation Authority to decide under what circumstances European banks can retain access to the UK. Whether the UK would be prepared to unilaterally grant access for EU financial institutions in order to retain the attractiveness of London as a financial centre, remains an open question. And let me add that it is of course not regulation alone that plays a role when European banks decide on opening a branch or a subsidiary in the UK. It is also a question of what kind of entity their counterparties and clients want to do business with.

Let me summarise the prospects for market access, at least from my point of view. Continued passporting rights are rather unlikely, and an equivalence decision would be a somewhat imperfect substitute. A transition period could ease some of the pressure, but it clearly is a sensitive issue.

Could a free trade agreement be the solution? According to their Brexit white paper, the UK government will strive for an ambitious free trade agreement with the EU as a long-term solution. But regardless of the fact that negotiating comprehensive free trade agreements is an arduous and time-consuming task, financial services are an especially tricky area. So far, the EU has never fully integrated finance in its free trade agreements with third countries.

Where does this lead us? So far, while acknowledging and accepting the divorce, policymakers are trying to find ways to hold the UK and EU economic areas and jurisdictions together. And they will continue trying so. The reason is that most of us are convinced that harmonised rules eliminate unnecessary frictions and act as a powerful catalyst for business across national borders – for the real economy as well as the financial sector. However, looking at the facts that I’ve just laid out we also have to acknowledge that it is at least questionable whether this undertaking will be easily achieved. Financial institutions should take into consideration that, in the end, there might well be two separate jurisdictions in which they operate, and that these jurisdictions might diverge over time – or instantly, once the divorce has gone through.

Global economy ‘on a knife edge’

In its First Half Outlook for 2017, fixed income research house BondAdviser said fiscal policy promises by US President Donald Trump have shifted deflationary market expectations back into “normal” territory.

Investors have regained confidence that inflation could finally be returning to global markets that appeared to be mired in deflation, said the report.

But the execution of fiscal stimulus policies by the new US president will be crucial to maintaining market confidence, said BondAdviser.

“Our analysis suggests the biggest issue for these policies will be choices the [US] Federal Reserve makes in regard to raising interest rates in the face of an arguably larger debt obligation,” said the report.

“As a general rule, central banks do not anticipate inflation (albeit market expectations are observed) but will wait until it actually emerges. Actual core inflation

(monthly) is only now in line with the Fed’s target average inflation rate of 2.00 per cent.”However, inflationary pressures will only persist if wage growth continues – something that is not guaranteed given the “structural headwinds” that technological advancements pose for the labour market.

“The global economy is poised on a knife-edge between inflation and deflation. The inflationary path could take hold, based on a combination of government spending (i.e. deficits) and low interest rates,” said BondAdviser.

“Conversely, the deflationary pressures could prevail, based on fundamental factors such as a strong US dollar, deleveraging, technology and Fed tightening.”

Trump to Order Dodd-Frank Review, Halt Obama Fiduciary Rule

President Donald Trump will order a sweeping review of the Dodd-Frank Act rules enacted in response to the 2008 financial crisis, a White House official said, signing an executive action Friday designed to significantly scale back the regulatory system put in place in 2010.

Trump also will halt another of former President Barack Obama’s regulations, hated by the financial industry, that requires advisers on retirement accounts to work in the best interests of their clients. Trump’s order will give the new administration time to review the change, known as the fiduciary rule.

Taken together, the actions are designed to lay down the Trump administration’s approach to financial markets, with an emphasis on removing regulatory burdens and opening up investor options, said the White House official, who briefed reporters on condition of anonymity.

The orders are the most aggressive steps yet by Trump to loosen regulations in the financial services industry and come after he has sought to stock his administration with veterans of the industry in key positions. His plans are sure to face fierce criticism by Democrats who charge that Trump is intent on undoing changes designed to protect everything from average investors to the global banking system.

He also could face a backlash from some of his own supporters, whose distrust of big banks and the financial industry helped fuel the populist anger that propelled Trump to the White House.

Banks ‘Shackled’

Trump is scheduled to issue the directives at a signing ceremony around noon following a meeting of more than a dozen top corporate executives led by Blackstone Group LP Chief Executive Officer Steve Schwarzman. Gary Cohn, director of Trump’s National Economic Council, is meeting with House Financial Services Committee members Friday morning, said two people familiar with his schedule.

Cohn said Friday on Fox Business that the executive orders are intended to relieve restrictions and scrutiny that post-crisis regulations have put on banks, and that firms have been forced to “hoard capital” rather than lend it out to their clients.

“All banks have been shackled,” Cohn said. “We need to get banks back in the lending business.”

On Monday, Trump promised to do “a big number” on the Dodd-Frank Act during a meeting with small business owners. He said the law had damaged the country’s “entrepreneurial spirit” and limited access to needed credit.

“Regulation has actually been horrible for big business, but it’s been worse for small business,” the president said. “Dodd-Frank is a disaster.”

What’s the problem with Dodd-Frank? — a Q&A explains

Trump’s Treasury secretary nominee, Steven Mnuchin, will meet with members of the Financial Stability Oversight Council and report back on what changes the administration should take to alter Dodd-Frank, the official said. Particular attention will be paid to the Volcker Rule limits on banks making speculative bets with their own funds, a restriction promoted by former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker.

Immediate Impact

The official wouldn’t say how long the Treasury Department would have to complete its review, but did say that the administration would be looking for ways to make an immediate impact, including through administrative changes and personnel decisions.

Trump’s directive also starts the process of stalling the so-called fiduciary rule — set to take effect in April — that the Obama administration said would protect millions of retirees from being steered into inappropriate high-cost or high-risk investments that generate bigger profits for brokers.

The review will include examining making personnel changes at financial regulators as a way of accomplishing the administration’s objectives, the official said. They declined to answer a question on whether Trump would try to fire Richard Cordray, the director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The official did say the administration believed that some of the rules created under Dodd-Frank may have been unconstitutional, including the creation of new agencies, an apparent

Asked Monday about whether Trump would retain Cordray in his position, White House press secretary Sean Spicer declined to answer. Mnuchin said during his congressional testimony that he believed the CFPB as a whole should be preserved but that Congress should take more direct control of its budget.

The Trump administration doesn’t believe Dodd-Frank measures, including the Volcker Rule, addressed real issues in the financial system, the official said. The president’s team also believes the Labor Department fiduciary rule was unnecessarily restricting investor choice without providing necessary consumer protection, the official said.

Republican lawmakers and some financial firms say the fiduciary rule is deeply flawed, arguing that it will restrict options for consumers and result in some savers being denied advice on their retirements. Trump will call for the Labor Department to stop and review the regulation in its entirety.

While the review will be undertaken independently by the Labor Department, the White House aide signaled that the president was expecting significant change.

Broader Overhaul

Delaying implementation of the Labor Department rule is the first step Republicans and the finance industry are eyeing as part of a broader overhaul of the measure. GOP Lawmakers have argued that the Securities and Exchange Commission, not the Labor Department, should oversee and regulate any changes related to financial firms.

Banks, asset managers and insurers have been fighting the fiduciary rule ever since the Labor Department approved it last year, saying the regulation could raise the costs of providing advice and make it harder to serve lower-income clients. Business groups including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and American Council of Life Insurers have sued to try to block it.

Still, representatives of some financial services companies said they planned to change practices to meet the regulation’s standard even if it is halted.

“We plan to go forward with the majority of the work we’ve done,” Bill Morrissey, managing director of business development at LPL Financial Holdings Inc., said in an interview before Trump’s order was disclosed. “What investors want is more transparency and lower fees.”

Morgan Stanley, one of the biggest U.S. brokerages, said on Jan. 26 it plans to move ahead with changes designed to comply with the rule, despite uncertainty over whether the regulation will be implemented. Insurers including American International Group Inc. and Principal Financial Group Inc. stressed after Trump’s victory that they would continue to forge ahead as though the rules would be carried out.

“My expectation is that a lot of firms are going to continue installing a best-interest standard, regardless,” said Brian Graff, chief executive officer of the American Retirement Association, a group that represents pension administrators and plan advisers.

Bank platforms ‘squeezing’ fund managers

Too much fund manager value is being “eaten up” by the high administration service fees of the major platforms, argues the ASX.

Speaking to InvestorDaily, ASX senior manager for investment products Andrew Campion said the investment management value chain should be more aligned with the people who actually generate wealth for investors – fund managers.

“We feel that presently too much value is eaten up by administration services. It’s not the actual person or firm that’s generating wealth for the end client,” Mr Campion said.

“If you squeeze the fund manager they just have less money to spend on research and less money to incentivise their staff,” he said.

This conviction is reflected in the relatively low fee ASX charges fund managers for inclusion on the mFund settlement service: 1.4 basis points (bps), or 0.014 per cent.

“If you look on a PDS for a fund manager and you see their expense ratio is 70 bps, 1 per cent or 1.2 per cent – they might be getting far less when they’re on a platform. Sometimes less than half as much,” Mr Campion said.

Sometimes a fund manager using larger platforms can be “squeezed” down to a fee of as low as 15 basis points “even though their direct retail fee structure is 70-80 bps or 1 per cent”.

“When we talk to managers, they’re staggered that they get to keep all of their fees,” Mr Campion said.

“We don’t feel like having a website that you can log into and have statements generated should cost 100 bps.”

There are now 170 products available on the mFund settlement service, with total funds under management (FUM) amounting to $250 million (up from $110 million 12 months earlier).

The ASX recently received approval from ASIC to include longer-form PDS products on mFund, in addition to shorter-form PDS products.

Longer-form PDS products, which include hedge funds, make up 20 per cent of the approximately $300 billion Australian retail fund management sector and are likely to be attractive to the mostly self-directed investors who use mFund, Mr Campion said.

“Although it’s only 20 per cent of the overall pie, we think as these funds come onto the platform it will be much more than 20 per cent of the mFund business,” he said.

Of the total $250 million in FUM on mFund, 40 per cent of it is self-directed and 60 per cent comes through advised channels, Mr Campion said.

Eighty per cent of the users of mFund are SMSFs, he added.

FED Holds Rate This Month

The FED held their benchmark rate today, whilst still leaving the door open for rises later.

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in December indicates that the labor market has continued to strengthen and that economic activity has continued to expand at a moderate pace. Job gains remained solid and the unemployment rate stayed near its recent low. Household spending has continued to rise moderately while business fixed investment has remained soft. Measures of consumer and business sentiment have improved of late. Inflation increased in recent quarters but is still below the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run objective. Market-based measures of inflation compensation remain low; most survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations are little changed, on balance.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. The Committee expects that, with gradual adjustments in the stance of monetary policy, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace, labor market conditions will strengthen somewhat further, and inflation will rise to 2 percent over the medium term. Near-term risks to the economic outlook appear roughly balanced. The Committee continues to closely monitor inflation indicators and global economic and financial developments.

In view of realized and expected labor market conditions and inflation, the Committee decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1/2 to 3/4 percent. The stance of monetary policy remains accommodative, thereby supporting some further strengthening in labor market conditions and a return to 2 percent inflation.

In determining the timing and size of future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will assess realized and expected economic conditions relative to its objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments. In light of the current shortfall of inflation from 2 percent, the Committee will carefully monitor actual and expected progress toward its inflation goal. The Committee expects that economic conditions will evolve in a manner that will warrant only gradual increases in the federal funds rate; the federal funds rate is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run. However, the actual path of the federal funds rate will depend on the economic outlook as informed by incoming data.

The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction, and it anticipates doing so until normalization of the level of the federal funds rate is well under way. This policy, by keeping the Committee’s holdings of longer-term securities at sizable levels, should help maintain accommodative financial conditions.

The Trump effect on bond markets and trade

The Australian bond market is likely to feel the effects of US President Donald Trump’s protectionist trade stance both directly and indirectly, writes Nikko Asset Management’s James Alexander.

The emergence of China is clearly of great importance to the economic fortunes of Australia, and as a result it may be tempting to downplay, or even overlook, President Trump’s agenda and its impact on Australia.

While our largest import and export partner is now China, Australia will still be impacted by US trade policy both directly and, perhaps more importantly, indirectly.

The difficulty for investors, however, is the general uncertainty around future US trade policy, and the impact the Trump administration will have on financial markets.

Uncertainty around trade

While most of President Trump’s comments so far have been directed at China and Mexico, we do know that he is not a fan of trade deals negotiated by others.

Trade deals he has criticised in which Australia has been involved include the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), from which the US has just withdrawn, and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

The essential message here is that these are bad deals for the US, as opposed to future Trump-negotiated deals, which will of course be good for the US.

It is likely to be some time before we can reasonably assess the impact of changes to US trade policy with Australia directly, given their larger trade relationships are most certainly ahead of us in the queue.

This brings us to the indirect but significant impact of the US’ future trade relations with our biggest trading partner, China.

A tit-for-tat trade war is likely to be harmful to both the US and China, with Australia most certainly suffering some collateral damage.

It is too early to tell how this relationship will unfold but the early signs are not great, with President Trump taking every opportunity to criticise China.

These two economic heavyweights have plenty of tools to ‘penalise’ each other on trade, which could potentially hurt Australian trade in the process.

Rising bond yields

The other broad area where the impact of a Trump presidency is likely to be felt is in financial markets – more specifically, bond yields and foreign exchange rates.

Australia’s bond yields have historically been strongly correlated with US Treasury yields and this is likely to continue.

If the Trump agenda of lower taxes, increased infrastructure spending and more protectionist trade policy prove to be inflationary as we expect, US interest rates and bond yields are likely to be headed higher.

Australian bond yields will surely follow, as Commonwealth bond yields must remain globally competitive to ensure international investors continue to support our borrowing needs.

Another widely discussed by-product of Trump’s agenda is a stronger US dollar.

While the Australian dollar has fallen by around 2.5 per cent against the American currency, it has actually risen slightly on a trade-weighted basis since the presidential election in November.

This divergence, should it continue, will be one to watch carefully.

While a weaker Australian dollar would indeed help to counter any negative impact from higher bond yields, weakness that is mainly isolated to the US dollar is not nearly as helpful as weakness on a trade-weighted basis.

James Alexander is the co-head of global fixed income and head of Australian fixed income at Nikko Asset Management.

Is Overvaluation Risk Real?

VIX Is Low, Overvaluation Risk Is Not

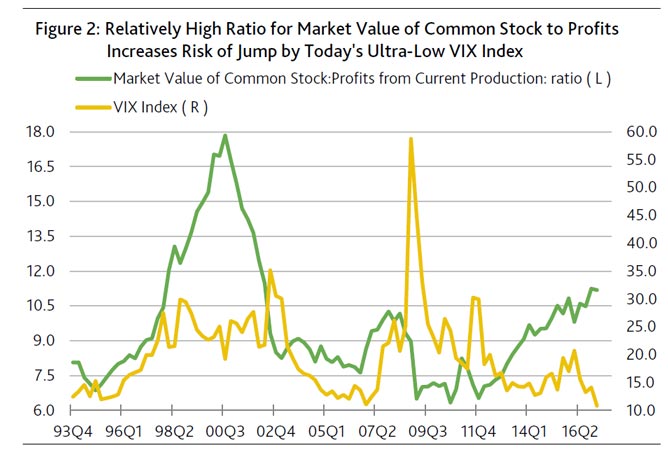

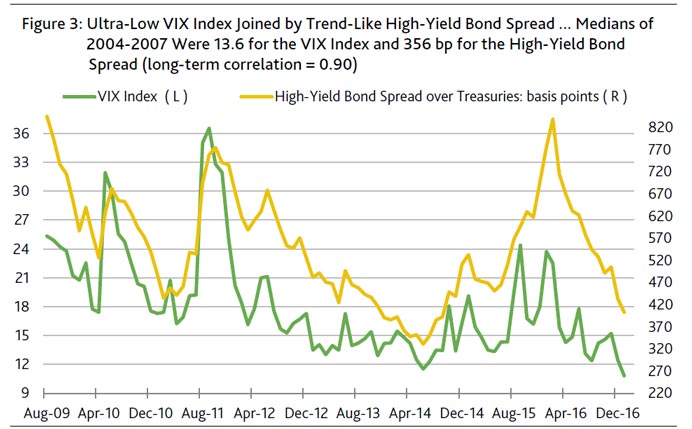

Overvaluation does not preclude an even higher market value of common stock relative to current and expected corporate earnings. Moreover, provided that the now extraordinarily low VIX index stays under 11.8, a further narrowing by corporate bond yield spreads is likely. However, an increasingly overvalued equity market favors a higher VIX index.

A convincing explanatory model for the high-yield bond spread employs measures of default risk and business activity, in addition to the VIX index. This model recently predicted a 411 bp midpoint for the high-yield spread, which eclipses its recent actual gap of 394 bp. By the way, the latter is the thinnest high-yield spread since September 2014.

What is now the lowest predicted midpoint since April 2015 owes much to an ultra-low VIX index. After removing the VIX index from the explanatory model, the predicted midpoint for the high-yield spread widens to 456 bp. (Figure 1.)

Record highs for stocks, not so for profits

For the first time ever, the blue-chip Dow Jones Industrial average broke above 20,000. Meanwhile, the market value of all US common stock as measured by the Wilshire Index set a new record high.

Nevertheless a popular measure of core profits, though improving, remains well under its apex. Since the moving yearlong estimate of pretax profits from current production peaked at the end of March 2015, the market value of US common stock has climbed higher by 10%. By contrast, the consensus estimates that for the year-ended March 2017, core pretax profits will still trail March 2015’s zenith by -5%. Moreover, the consensus does not expect yearlong profits to eclipse its record high until 2018’s second quarter.

As inferred from the different directions taken by share prices and profits since March 2015, the US equity market is richly priced, if not significantly overvalued. However, overvaluation does not promise impending doom for share prices.

For example, during 1998-2000’s stock market frenzy, though overvaluation first resembled today’s excesses in 1998’s second quarter, the market value of US common stock continued its ascent until March 2000 despite becoming increasingly overvalued. Amazingly, notwithstanding the accompanying -7% drop by yearlong profits from December 1997’s peak, the market value of US common stock managed to soar by a cumulative 49.5% from 1997’s final quarter through the first quarter of 2000.

Not surprisingly, March 2000’s unprecedented overvaluation of equities set the stage for a cumulative -43% plunge to October 2002’s bottom. Granted that today’s overvaluation falls considerably short of the excesses of late 1998 through early 2000, buying into an overvalued market necessarily entails above-average risk.

Based on the historical record, the current rally may not expire soon. Absent another extended bout of profits deflation, the US equity market is likely to set new records regardless of today’s overvaluation. For now, the consensus expects pretax operating profits to grow through 2018.

Interest rate risk now poses the biggest danger to stocks.Nevertheless, substantially higher interest rates could temporarily drive the market value of US common stock down by at least -5%. Sharply higher interest rates previously outweighed the positive effect of profits growth and temporarily sank share prices in 1994 and late 1987. In both instances, deep declines by interest rates allowed profits to re-assume its leading role as the primary driver of equity valuation.

Incredibly, 1987’s outsized 19% annual advance by core profits was not enough to prevent a stock market crash of frightening severity. In late 1987, the market value of US common stock plunged by as much as -27% from its then record high largely because of a lift-off by the 10-year Treasury yield from a January 1987 average of 7.08% to the 10.36% of October 17, 1987.

In fact, it was at the morning of October 19, 1987’s infamous -18% daily plummet by the market value of US common stock that the benchmark Treasury yield was last above 10%. Who would have thought back then that 30 years later markets would fret over the possibility of a 3% benchmark Treasury yield?

Regarding 1994’s far less dramatic episode, a climb by the 10-year Treasury yield’s month-long average from October 1993’s 5.3% to April 1994’s 7.0% helped to sink the market value of common stock by -5.3% from its then record high despite an accompanying 19% annual advance by profits.

Do not underestimate the power of sharply higher benchmark interest rates to pummel share prices. The equity market sell-offs of both 1994 and 1987 occurred despite significant narrowings by medium- and low-grade bond yield spreads. Nor did the declining trends of high-yield defaults offset the selling pressure arising from fast rising Treasury yields.

As inferred from what occurred in 1987 and 1994, the 10-year Treasury yield may need to approach 3% for there to be at least a 50% likelihood of a 5% drop by equities amid profits growth. However, the record also makes clear that an especially disruptive ascent by benchmark yields is likely to be reversed. In order to stabilize share prices, the 10-year Treasury yield’s month-long average fell to 8.21% by February 1988 and to 5.65% by January 1996.

VIX Index stays low despite risks surrounding overvalued equities

Overvaluation warns of a painful correction in the event market sentiment worsens considerably. In recognition of ample downside risk, the VIX index has tended to be greater in richly priced equity markets, where above-trend VIX indexes have typically been joined by above-average corporate bond yield spreads. (Figure 2.)

In the current market, however, the VIX index has broken from the norm and remained unexpectedly low amid elevated ratios of equity’s market value to core profits. The market value of US common stock recently approximated 11.2-times the yearlong estimate for pretax profits from current production for the highest such ratio since the 11.5:1 of 2002’s second quarter. It was in 1998’s first quarter that common equity’s market value last climbed up to 11.2-times core profits. At that time, the VIX index averaged 21.3, which was far above its recent 10.8. Similarly, when the ratio of common equity’s market value to profits rose to Q4-2007’s previous cycle high of 10.3:1, the VIX index averaged a well above-trend 22.1. Thus, the longer elevated price-to-earnings ratios persist, the more likely is a climb by the VIX index that ordinarily is accompanied by wider corporate yield spreads.

On January 24, 2007 the VIX index closed at a record low 9.89. Ten years later the VIX index closed at the 10.83 of January 25, 2017. The latter was its lowest finish since the 10.32 of July 3, 2014, or when the high-yield bond spread was an exceptionally thin 322 bp. However, even that gap was wider than the 276 bp of January 24, 2007. Do not be surprised if an ultra-low VIX continues to lead the high-yield bond spread lower.

According to the historical statistical relationship, by itself, the recent VIX index of 10.9 predicts a 326 bp midpoint for the high-yield bond spread, which is much thinner than the recent 394 bp. As shown in Figure 3, exceptionally low readings for the VIX index have tended to prompt narrowings by the high-yield spread throughout the current business cycle upturn. (Figure 3.)

Deutsche Warns Global Economy About To Roll Over, Says “Sell”

When Trump unexpectedly won the election, and futures staged one of their most dramatic rebounds in history, surging from limit down to solidly in the green, Wall Street promptly goalseeked their economic assumptions “chasing the price”, quickly going from bearish to bullish, and nobody did it faster or more conclusively than Deutsche Bank, which seemingly overnight flipped from one of the biggest bearers of gloom on the outlook for the US economy, to one of its biggest cheerleaders.

That however changed overnight, when DB’s European equity strategist Sebastian Raedler highlighted that, according to the latest flash PMIs, global growth momentum hit a six-year high in January.

And with global macro surprises close to their all-time high – much of which has been predicated on the relentless debt-creation by China which just got instruction to slow down dramatically in the current quarter – the DB strategist says they are likely to roll over from current elevated levels, resulting in a slowdown in global growth in the coming months.

From his full set of observations, first here are the good news:

Global growth momentum hits a six-year high: in mid-January, our indicator of global macro surprises rose to 45, the highest level since May 2010. This points to a further rise in global manufacturing PMI new orders from the December level of 53.7, implying they are now at a six-year high and consistent with 2017 global GDP growth of 3.5% at market FX terms (a sharp acceleration from the 2.6% realized growth over the past four quarters).

The rebound in growth momentum has been the main driver of the sharp moves in asset prices over the past six months:

- Global equities have continued to track global macro surprises over the past year (with an R2 of 70%), rebounding by 15% on the back of the 50 point rise in macro surprises since mid-2016;

- US 10-year bond yields have moved in line with global PMIs since the end of the financial crisis in 2009 (with an R2 of 75%): after the Brexit vote in June 2016, they had undershot this relationship (pricing in a sharply negative growth shock), but then rebounded by 100bps to re-couple with improving growth momentum (though, at 2.5%, they are still slightly below the fair-value level suggested by that relationship, at 2.8%, potentially because of the technical obstacle of extreme short positioning).

- European cyclicals versus defensives have rebounded by 25% since early July to reach a 10-year high, the sharpest cyclical rally since 2009, in line with rebounding macro surprises.

And now the bad:

We believe global macro momentum is likely to roll over from current elevated levels:

- Global macro surprises have only been higher 5% of the time since 2003 (when the data series starts), typically roll over from these elevated levels and have shown first signs of softening over the past week;

- Global PMIs are already consistent with global GDP growth 50bps above our economists’ 2017 growth forecasts of 3%, despite the fact that the latter incorporate aggressive assumptions for fiscal stimulus in the US;

- Chinese PMIs are already close to a six-year high, having rebounded by 7 points over the past 15 months. They point to quarterly annualized GDP growth of 8%+ (above the government’s target of 6.5%) and the credit impulse (a key driver of SoE fixed asset investment) is set to turn negative. This suggests the risk to Chinese growth momentum is now to the downside;

- Our model of global PMIs suggests global growth momentum has rebounded because of the easing in financial conditions due to tighter HY spreads and a reduced drag from USD strength as well as lower global uncertainty. However, it also implies that the rebound in growth momentum should start to fade, as the lagged benefit from falling commodity prices is wearing off.

Not surprisingly, it will all start with the world’s “marginal” growth economy China:

So if DB is right and the global economy is about to roll over, just as Trump begins his presidency, how should one trade it? Simple: by derisking, i.e. selling stocks.

Trade recommendations: Lower macro surprises would be consistent with a tactical pull-back for equities (especially against the backdrop of still-elevated readings on our market sentiment indicators) as well as a roll-over in cyclicals versus defensives.

DB’s conclusion: “the equity market looks stretched“, and furthermore the bank’s proprietary exuberance indicator has continued rising above a level of 70: “in 7 out of 8 instances over the past 10 years, the market has fallen over the following month (by up to 10%, but 2% on average).”

Finally, there is no more “cash on the sidelines” – cash holdings for US mutual funds are close to a 5-year low, suggesting that little money remains on the sideline waiting to come into the market.