Economist John Adams is back in the studio with Analyst Martin North to look at the likely trajectory of home prices. Given all the talk about what may happen, we ask, what might keep them up?

This is not financial advice.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

Economist John Adams is back in the studio with Analyst Martin North to look at the likely trajectory of home prices. Given all the talk about what may happen, we ask, what might keep them up?

This is not financial advice.

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Bookmark our upcoming live event on May 2020 Mortgage Stress, Tuesday 2nd June 20:00

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Join Edwin and I for a special discussion on property. Ask a question live via the YouTube chat, or send in questions beforehand via the DFA Blog.

Why is the property industry facing a rocky future? What are the true market indicators saying?

Mark your diary, and spread the word. This will be quite something!

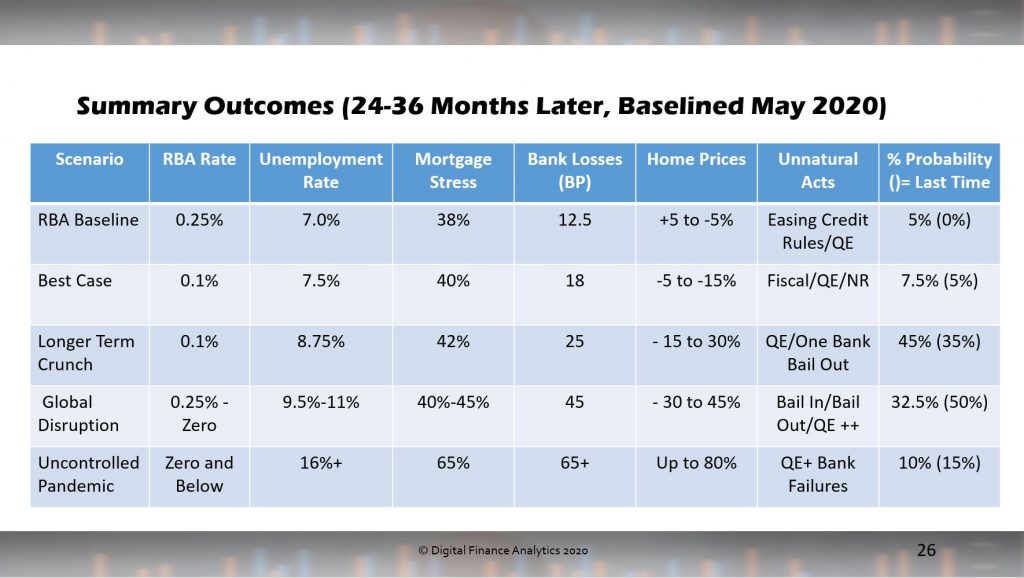

This is the edited show broadcast live on 19th May 2020. We discussed our latest finance and property scenarios, the latest news and also walked through our mortgage stress data for selected requested post codes.

There is a path to higher home prices due to lower rates in line with the RBA market model, however it ignores availability of credit. The “Tulip” model weirdly takes little account of the credit drivers.

Most likely though unemployment will remain higher, while incomes are squeezed and so we have a stronger weighting on FALLS in property values over the next couple of years. How far they fall, and where, will be determined by how much stimulus is thrown at the economy, the migration settings and bank’s willingness to lend in a weaker employment and income environment.

You can watch the edited show here:

Note in the show we were comparing the ratios to the total household population in each post code.

The unedited original stream, with live chat is also available here:

The latest edition of our finance and property news update – including puppies today – with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Journalist Tarric Brooker and I discuss the vexed question of home prices in the context of the current political and economic backcloth to the lock down. Tarric uses the handle @AvidCommentator on Twitter.

Tarric’s Article:

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Upcoming May 5th Live Q&A – remember to bookmark!