Welcome the latest edition of the Property Imperative Weekly to 2nd June 2018, our digest of the latest finance and property news with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Watch the video, listen to the podcast, or read the transcript.

Watch the video, listen to the podcast, or read the transcript.

The average home value fell in May 0.1% and took the annual change down (-0.4%) and into negative territory for the first time since October 2012 according to the latest CoreLogic index. May marked the eighth consecutive month-on-month fall since the national market peaked in September last year, taking the cumulative fall in dwelling values to 1.1% through to the end of May 2018. This was caused by weaker conditions in Sydney and Melbourne, although some regional centres did move higher. But the sheer weight of numbers means the overall index is hit when Sydney and Melbourne fall, as around 60% of properties are in these two centres.

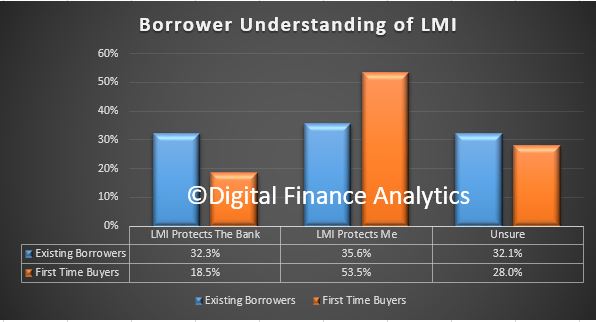

The root cause of the falls is simple; credit is harder to get. Our surveys show that up to 40% of applications for mortgages are now being turned down, compared with just 5% a year ago, as lenders apply more forensic analysis of applications received. For example, as we discussed yesterday, CBA is now looking at applications with a loan to income of 4.5 times and above, – see our post A Deeper Dive into Loan To Income Ratios. And I am getting more reports of households who are finding their available borrowing power is as much as 35% down on a year ago.

So unlike the small correction which occurred to the CoreLogic Index in 2015, as credit was harder to get briefly, and which reverted a few months later, we think it’s different this time.

As we discussed in our post What’s Happening to Bank Lending? the RBA released their credit aggregates to April 2018. Total mortgage lending rose $7.2 billion to $1.76 trillion, another record. Within that, owner occupied loans rose $6.4 billion up 0.55%, and investment loans rose just 0.14% up $800 million. Personal credit fell 0.3%, down $500 million and business lending rose $6.3 billion, up 0.69%. The annualised stats show owner occupied lending is still running at 8%, while business lending is around 4% annualised, investment lending down to 2.3% and personal credit down 0.3%. On this basis, household debt is still rising. But the Bank lending data from APRA showed that tighter lending standards are biting. In fact, Westpac apart, all the majors reduced their investor property lending in April. Owner occupied loans grew by 0.29% or $3.1 billion to $1.07 trillion while investment loans fell slightly, down 0.01% or $42 million. As a result, the relative share of investment loans fell to 34.14%.

Melbourne has taken over from Sydney as the weakest performing housing market over the past three months with a 0.5% fall in values over the month of May to be 1.2% lower, over the previous three months. This is the largest decline in Melbourne dwelling values over a three-month period since February 2012. We expected this, as Melbourne’s housing market was running ahead of Sydney, but recently auction clearance rates have been deteriorating, inventory levels are rising and transaction activity is tracking 12.9% lower than one year ago.

In Sydney home prices showed a month-on-month fall, down 0.2%, Perth was down -0.1%, Darwin down -0.2% and Canberra down -0.1%. Sydney was the only capital city other than Melbourne to record a decline in dwelling values over the past three months, with a 0.9% fall. Hobart’s impressive run of capital gains continued and is showing little signs of slowing down with dwelling values jumping 0.8% over the month to be 3.7% higher over the rolling quarter and 12.7% higher year-on-year. But of course it’s a small market.

Again we are seeing the strongest falls at the top end of the market, as we discuss last week. In Sydney, the most expensive quarter of the market has seen dwelling values fall by 7.1% since peaking compared with a 1.4% fall across the least expensive quarter of the market and a 3.3% decline across the broad ‘middle’ of the market. Similarly, in Melbourne, the most expensive quarter of the market is down 3.3% since peaking, while the broader middle market saw dwelling values fall by 0.8%. The most affordable quarter of properties did not decline at all, remaining at record high values. Because of the price differential, units are performing a little better than houses.

It is also worth looking in more detail at the regional areas, as we see significant variations. CoreLogic says that across the regional markets, Geelong retained its position as the best performing area outside of the capital cities with dwelling values up 10.2% over the past twelve months. The top ten performing regional markets are a mix of satellite cities such as Geelong, Ballarat and Newcastle, as well as lifestyle markets such as the Sunshine Coast, Southern Highlands, Shoalhaven and Coffs Harbour. Regional housing trends are also now seeing less drag from the mining regions. Although the weakest performing areas are generally still linked to the mining and resources industry, the declining trend has eased or even levelled across many of these markets. Mackay in QLD was the worst performing area down 10.6% year on year.

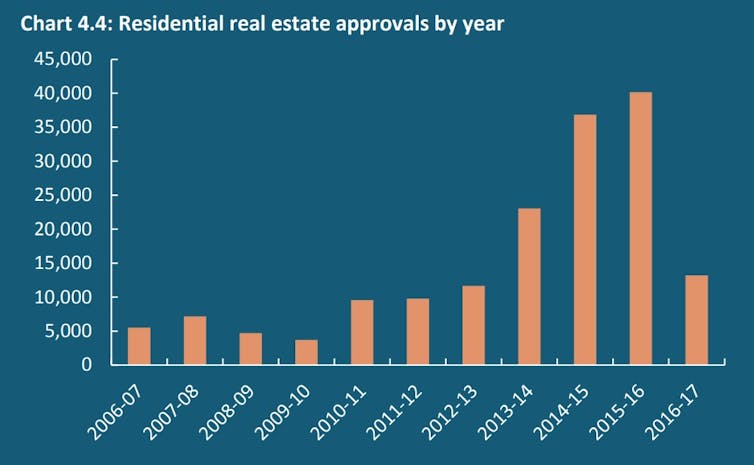

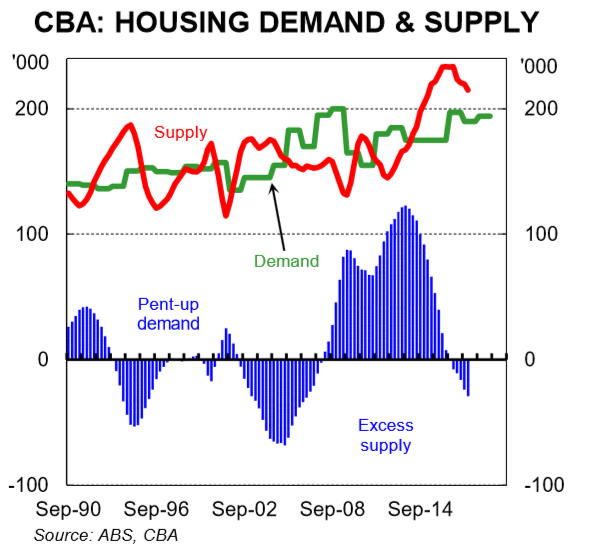

Credit availability apart, demand for property is falling, with investors still coy about buying, and some in fact looking to sell before prices fall further. And the latest data from the Foreign Investment Review Board shows that the number of foreign buyers have fallen. Whereas in the year 2015-16 saw 40,149 approvals granted, totalling A$72.4 billion, the figure for the following year was just 13,198 approvals, totalling A$25.2 billion. On these numbers, the foreign property investment boom looks to be over. By the way, the data is still only reported at a high-level, and so we do not have much insight below the top line numbers from the FIRB. This needs to be addressed.

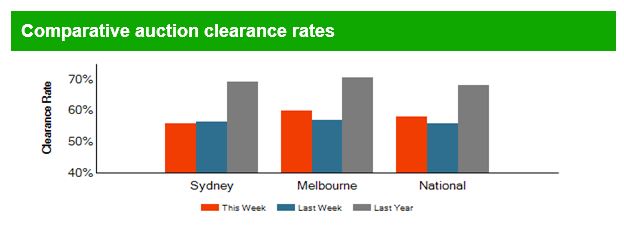

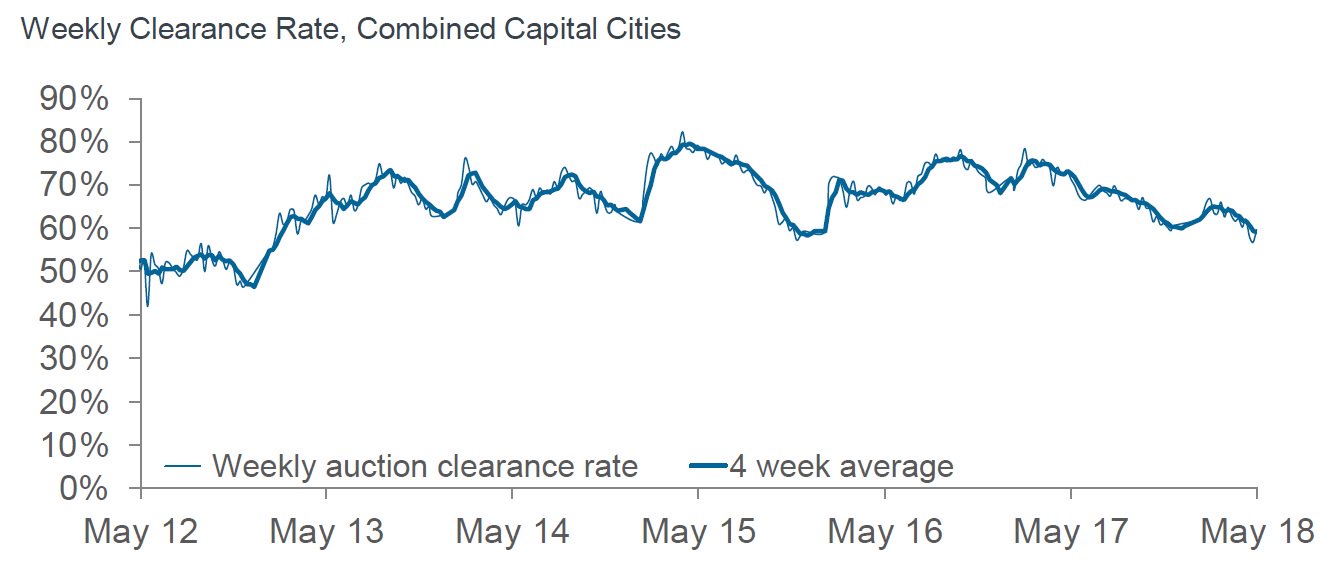

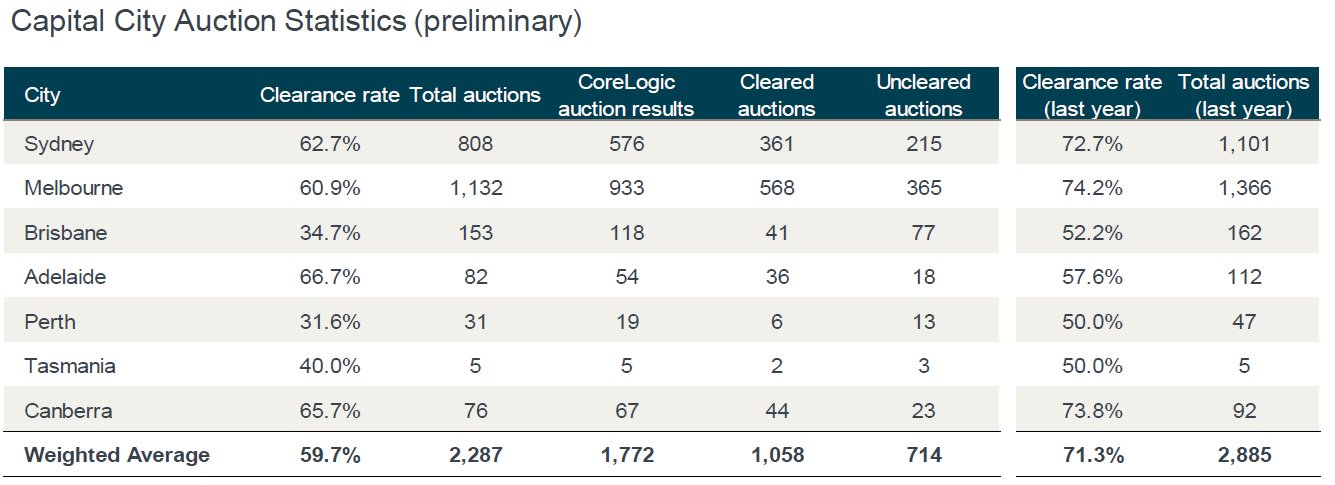

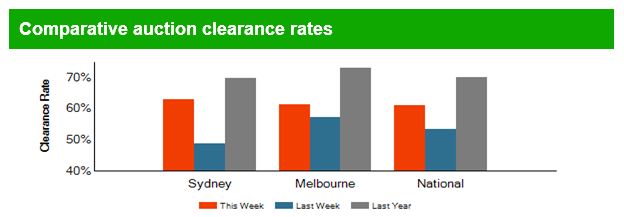

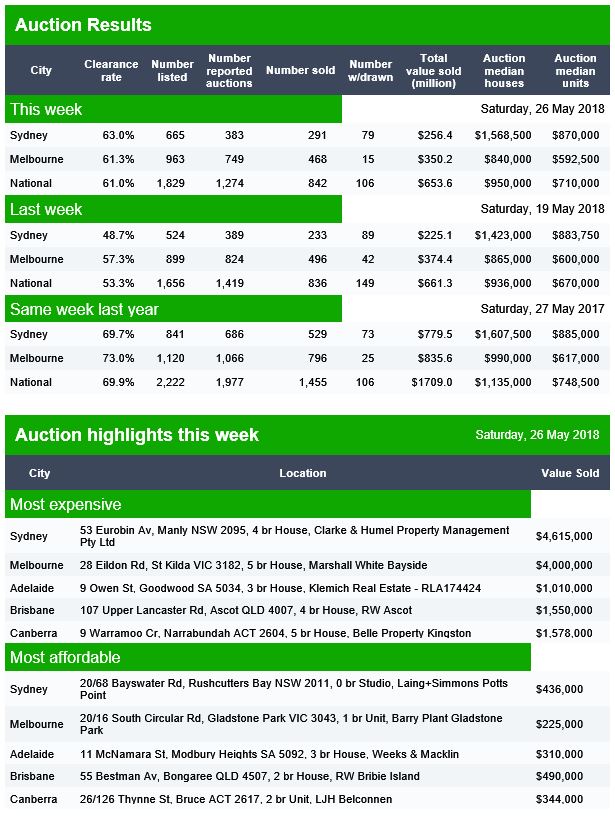

All this is reflected in the weaker auction clearance results. CoreLogic reported that the overall final auction clearance rate fell to 56.2 per cent last week; the third consecutive week where the weighted average has progressively declined. There were 2,297 homes taken to market which was only slightly higher than the week prior, when 56.8 per cent cleared. The last time clearance rates were tracking at a similar level was in early 2013 though then volumes were down thanks to the January lull.

In Melbourne the final clearance rate dropped below 60 per cent, with 59 per cent of auctions successful down on the 62 per cent the previous week. In Sydney, both auction volumes and the final clearance rate increased last week, with 814 auctions held returning a final auction clearance rate of 56.1 per cent, which was higher than the 54 per cent over the previous week. Adelaide, Canberra and Perth all saw a week-on-week improvement in clearance rates, while Brisbane and Tasmania’s clearance rate fell. Across the non-capital city regions, the highest clearance rate was recorded across the Hunter region, with 72.4 per cent of 54 auctions successful.

CoreLogic is tracking 2,121 capital city auctions this week, down slightly on last week’s 2,297, with weekly volumes remaining relatively steady over past month while the weighted average clearance rate has continued to weaken. Over the same period one year ago, there was a considerably higher 2,578 auctions held.

So, have no doubt, prices have further to fall – Gravity is winning, in markets where on a fundamental basis property is still over valued by up to 40%.

The lift in the minimum wage by 3.5% for more than 2 million Australian which was announced this week will lift wages to $719.20 a week a rise of an extra $24.30 for a 38-hour week, from July 1. Trade Unions wanted an increase of $50 a week, arguing it would help Australians grappling with the rising cost of living. The increase may add up to 0.5 per cent to the Wage Price Index, which has been bumping along at, or near, historic lows of 2 per cent growth annualised for almost three years. But as 80 per cent or so workers not on a minimum wage, we are not sure this will have any visible impact on home price moves.

The Big Banks had a further terrible week, as the ACCC confirming that criminal cartel charges are expected to be laid by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions against ANZ, Deutsche Bank and Citigroup, as its alleged the joint lead managers took up approximately 25.5 million shares of and ANZ share placement in 2015. This represented approximately 0.91% of total shares on issue at that time. This is a criminal case, rather than civil, and carries potentially much higher fines – at 10% of turnover as well as imprisonment. ANZ share price was down significantly, despite still been the darling among the big 4 for many analysts!

The ACCC also warned more cartel cases are in the works.

Separately, CBA said that an investigation was initiated after a concern raised about internal CBA emails being inadvertently sent to email addresses using the cba.com domain prior to April 2017 when the bank acquired ownership of the cba.com domain. CBA’s email domain is cba.com.au. CBA acting Group Executive Retail Banking Services Angus Sullivan said: “We want our customers to know that we are committed to being more transparent about data security and privacy matters. “Our investigation confirmed that no customer data has been compromised as a result of this issue. We acknowledge however that customers want to be informed about data security and privacy issues and we have begun contacting affected customers.” CBA’s chare price was down to a five year low, in reaction to the battery of bad news in recent times, as well as weaker home lending trends.

And at the Royal Commission more poor bank behaviour was revealed in the handling of small business customers, thanks to errors and more deliberate intent. As we discussed in our post The Problem with Small Business Lending, banks make a risk assessment of a business from the perspective of loss of a loan as a prudent banker, not the overall business performance. The commission is not recommending that any additional statutory obligations should be imposed for small business lending. But the banks, and ASIC have issues to answer, as outlined in the closing statements. I felt ASIC’s approach to regulation was shown up.

The royal commission also announced the new focus for the hearings that will commence on Monday, 25 June in Brisbane and end on Friday, 6 July in Darwin. Misconduct in regional financial services is one of the key issues that first ignited calls for a royal commission by advocates like Nationals Senator John Williams.

Turning to the broader financial market scene, the volatility index – the VIX, is still sitting around 13, somewhat elevated compared with a few months ago, but well off its highs. But markets were rocked by the return of tariff tantrums and geopolitical uncertainty in the Eurozone before shifting to US domestic issues as a bullish jobs report helped steady risk appetite. The unemployment rate fell again, though wages remained pretty flat. Private payrolls grew by 223,000 for the May, a sharp uptick from the 163,000 in April, which beat economists’ forecast of 189,000. That provided the impetus for U.S. stock to recoup some of their losses which followed fears that a global trade war beckons. U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminium imports from Canada, Mexico and European Union were triggered, drawing retaliatory measures from all three of the United States’ allies. U.S. markets were also disturbed by Italian political turmoil, which has since abated after Giuseppe Conte was sworn in as Italy’s new Prime Minister. The S&P 500 closed roughly flat for the week.

Crude oil prices adding to their 5% loss last week, with a 3% slump this week following an expansion in U.S. oil output and uncertainty on whether OPEC and its allies would ease limits on production. As the OPEC meeting slated for June 22 draws closer, traders remained wary of the oil-cartel easing production limits despite a Reuters report mid-week, citing a Gulf source, OPEC and its allies would stick to production curbs, which have helped slash the glut in global supplies. Fears that limits on the production-cut agreement could be eased overshadowed a weekly Energy Information Administration report showing U.S. crude supplies unexpectedly fell by 3.6 million barrels in the week ended May 25. Crude futures settled 1.8% lower on Friday as data showed U.S. oil rigs increased, pointing to signs of growing domestic output.

The US dollar scraped its third-straight weekly win after a strong jobs report Friday helped the greenback recover some of its early-week losses, paving the way for the Federal Reserve to hike rates in June and helping the greenback steady against its rivals. The greenback suffered heavy losses on Wednesday after uncertainties in Italy, but the last-ditch talks by Italy’s Five-Star Movement and League were successful as Giuseppe Conte was sworn in as Italy’s new Prime Minister on Friday. The dollar rose 0.24% to 94.18 against a basket of major currencies on Friday.

Gold prices were unable to add to their gains from last week, posting a weekly loss as the prospect of the further Fed rate hikes in the wake of the upbeat jobs report reduced demand. Analysts warned, however, that a single jobs report, albeit solid, was not enough to warrant a faster pace of rate hikes. “Average hourly earnings at 2.7% year-on-year is within the range it has trended since mid-2016 and not enough to warrant a faster pace of rate hikes,” analysts at CIBC said in a note.

Upward pressure on funding will come from higher US rates if the Fed does move in June as expected. The US 10 Year Treasury rose 0.25% on Friday, and if off its recent lows, on the expectation of rate hikes ahead.

Bitcoin saw lower lows this week but its test of $7,000 was met with a wave of buying, stoking hopes of a recovery in the popular crypto. Some analysts said earlier this week that the $7,000 region triggered some “very key” support for bitcoin, opening the door to a possible recovery. Yet, traders continued to adopt a cautious approach, appearing unwilling to make a meaningful return to the crypto space as data showed the crypto total market cap remained stagnant compared to last week. The total crypto market cap was roughly unchanged from a week ago at $329 billion. Over the past seven days, Bitcoin fell 0.09% on the Bitfinex exchange, Ethereum fell 2.69%, while Ripple XRP rose 0.79% on the Poloniex exchange.

So overall, we think the home price data will continue to deteriorate further against a backcloth of international financial uncertainly. In his opening statement to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee, Wayne Byres, APRA Chairman said that Australians can be reassured that the finance industry is financially sound, and that the financial system is stable. So that’s OK then!

Before I sign off, I wanted to highlight our planned live question and answer session which is scheduled for next Tuesday, at 8 PM Sydney Local Time. This will be streamed via YouTube, and I plan to take questions live via the built in YouTube Chat facility, as well as answer questions which I have yet to address in my posts from earlier conversations. The session will be posted as a normal post afterwards, so you can choose to send questions through over the next few days, join me live on Tuesday at 8 pm, or watch the session afterwards. I hope to see you there and remember to mark your diary. I have put it up as a scheduled event on YouTube.