Infrastructure in our cities – let’s call it the hardware – remains much the same as ever, but the software – the way we use it – is transforming rapidly. One piece of that software, Airbnb, is dramatically reshaping the world’s cities.

The digital platform allows citizens to find and rent short-term accommodation from other citizens. Airbnb has the potential to rupture the traditional spatial relationship between tourist and local, making our cities more vibrant and diverse places to live in and to visit.

The question is: what opportunities and dangers does the platform present? What are the implications of repurposing existing residential infrastructure for short-term accommodation? What happens when the global “sharing economy” meets a city’s suburbs?

Lessons from an early adopter

Melbourne was an early adopter of Airbnb. It is also one of the top 10 cities for global travellers on Airbnb. What insights can be gathered from its experience?

According to Airbnb, three-quarters of listings worldwide are outside major hotel districts. Airbnb has three types of property listings: entire homes, private rooms and shared rooms.

Concentration of Airbnb entire-house rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

Concentration of Airbnb entire-house rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

Entire homes make up over half the total number of Melbourne’s metropolitan listings. Data collected in January 2016 reveals that their distribution is relatively consistent with that of hotels and licensed accommodation, which exist in large concentrations in the CBD and inner city. Many hosts who list entire homes lease or sublet when they go away.

In Australia, tenants require permission from their landlord to sublet, so there is little risk for the landlord if they follow due process. But analysis by website Inside Airbnb indicates that about 75% of entire-house listings in Melbourne are available for over 90 days per year. Hosts with multiple properties manage about a third of all the entire-house listings in Melbourne. These operators hold an average of three properties, but some have dozens. Through Airbnb, these brokers are turning existing housing infrastructure into informal, distributed hotels while saving on capital costs, overheads and wages.

Globally, the Airbnb phenomenon has been blamed for driving up rents, accelerating gentrification and displacing local residents by reducing available housing stock. In Melbourne, the boom in high-density development in the CBD has resulted in an excess of homogeneous apartment dwellings. Bedrooms without natural light, as well as insufficient floor area, outdoor space and storage space, characterise many of these developments, rendering them effectively unlivable for long-term residents. But these properties are attractive to itinerant tenants seeking affordable inner city accommodation.

Concentration of Airbnb shared-room rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

Concentration of Airbnb shared-room rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

Shared rooms in Melbourne constitute only about 2% of all listings, but they are almost exclusively confined to the CBD. Box Hill (14 kilometres east of Melbourne), and Maidstone/ Braybrook (eight kilometres west of Melbourne) are secondary outlying hotspots. The majority of CBD listings are around new apartment towers near Southern Cross Station (at the western end of the CBD) and RMIT University.A number of already small two-bedroom apartments in the Neo200, Upper West Side and QV1 towers are operating as gendered dormitories. These often sleep eight, with four to a room. Overloading these apartments creates potential fire-safety and hygiene-compliance issues.

Short-term letting via sites like Airbnb allows investors to earn up to three times the amount they’d receive in rent (the average cost to rent an entire home is AU$189 per night). Travellers benefit from competitive accommodation rates, cooking facilities, convenient locations and access to private pools and gymnasiums intended for residents.

Airbnb acknowledges that professional hosts with multiple listings are exploiting the so-called sharing economy, but has not yet taken steps to regulate this. Governments would do well to implement the long-awaited and much-needed minimum design standards for apartments to curb the construction of developments in the city that fail to cater for residents or which are purpose-built for the Airbnb market (a few local examples are already emerging).

Beyond the obvious need to protect the amenity of citizens, protection of the liveliness and heterogeneity of the city is essential to maintain the kind of “authentic” experience that appeals to Airbnb users in the first place. Melbourne is beginning to follow the trajectory of international cities like London where the investor market, fuelled by capital gains tax exemptions, has pushed residents further and further out. Dispersing the concentration of entire-house and private-room rental is vital.

Concentration of Airbnb private room rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

Concentration of Airbnb private room rentals in Melbourne. Jacqui Alexander & Tom Morgan, Author provided

More promising is the dispersed pattern of private rooms in Melbourne. These represent around 45% of listings across the city. While private rooms are still concentrated in and around the CBD, diffuse listings across Melbourne’s middle-ring suburbs realise Airbnb’s ambition to enable access to the everyday spaces of cities. This pattern makes sense given the mismatch between Australian house sizes, which remain the largest in the world, and changing household structures – most significantly, the decline of the nuclear family. An increase in housing diversity in the middle-ring suburbs is likely to facilitate more entire-house listings in these areas in the future.

We are also seeing evidence of Airbnb driving housing diversity. Annexed and granny-flat configurations are commonly listed in suburbs close to the Melbourne CBD like Brunswick and Caulfield. Loose-fit arrangements like these provide more flexibility to cater to both residents and visitors, and the by-product is slow but genuine “bottom-up” densification.

Government incentives for this kind of small-scale development would help to make this a viable (and, for many, welcome) alternative to densification through high-rise apartment development.

In 2015, Tourism Victoria entered into an agreement with Airbnb Melbourne to promote buzzing inner-city suburbs Fitzroy and St Kilda as “sharing economy” hotspots. But the cost of renting in these suburbs is already exorbitant. Fitzroy was named the second-most-expensive suburb in Melbourne for apartment rental in 2015.

Instead, policymakers could encourage disruption in the suburbs that would benefit both sides.

What can be done to capture local benefits?

Airbnb claims that tourists who use the platform “stay longer and spend more”. Through taxation and additional revenue from the sharing economy, governments could fund more extensive and efficient transport networks to service both locals and visitors. Extending transport infrastructure would support the intensification of distributed neighbourhoods and maximise intermingling between tourists and locals.

Airbnb rentals in Perth. Jacqui Alexander, Author provided

Airbnb rentals in Perth. Jacqui Alexander, Author provided

Bottom-up densification could also be a way forward for Perth. The distribution of Airbnb accommodation towards Perth’s coastal suburbs highlights potential in this space: here, tourism-specific and local infrastructure can converge. This is an exciting prospect for a state that positions itself as a unique travel destination.

Airbnb emerges from the same cultural tendency as the pop-up shop and interim-use place activation. Built environment professionals must recognise it as an urban issue and lead with a framework for targeted, productive disruption.

Airbnb can increase the density of people within existing building stock, while dispersing the positive effects of the tourist economy. This requires more imagination from planners and designers, who first and foremost must consider the interests of individual citizens, whether they are renters or home owners.

Can Airbnb be a part of the solution of increasing urban infill without compromising a minimum standard of living?

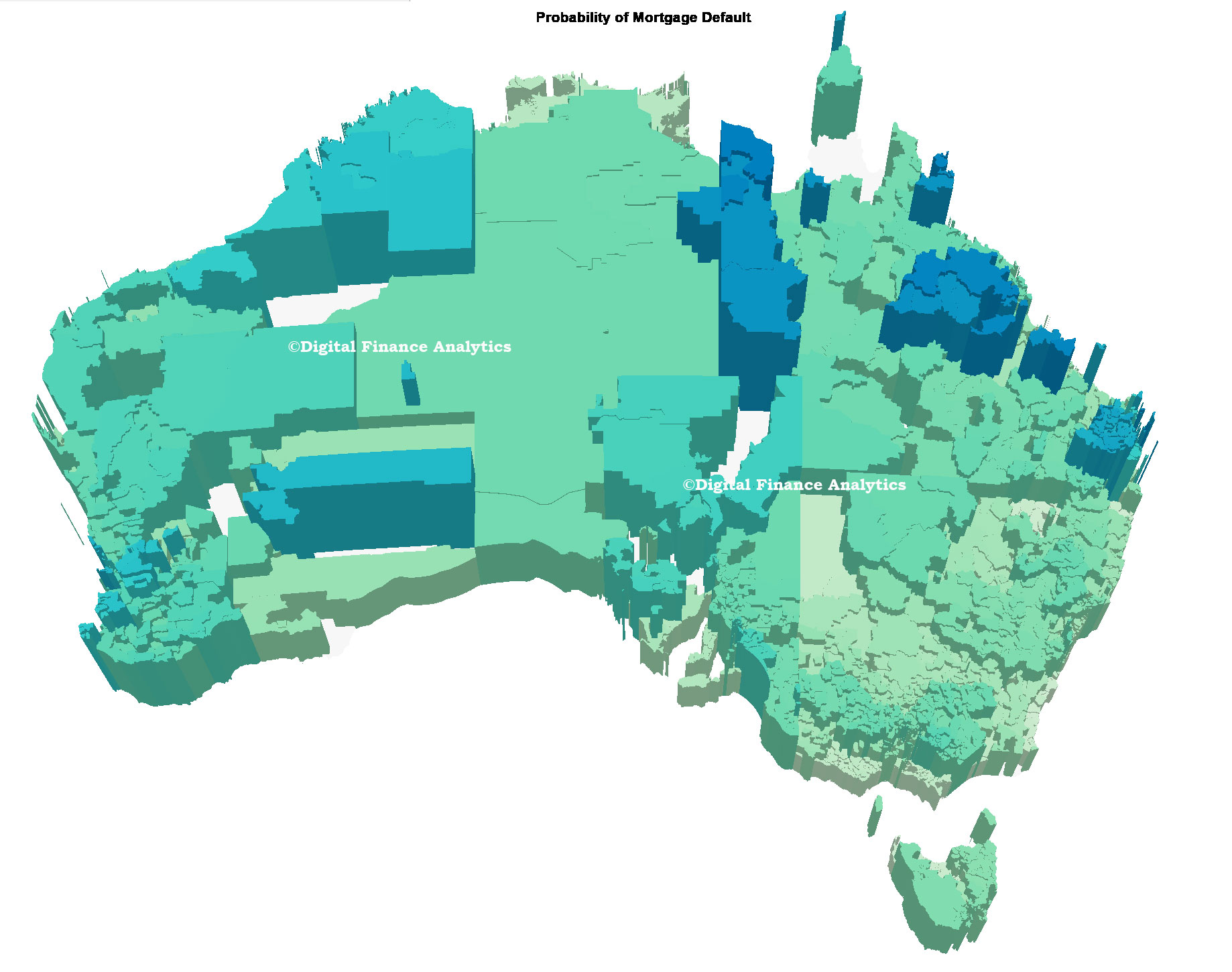

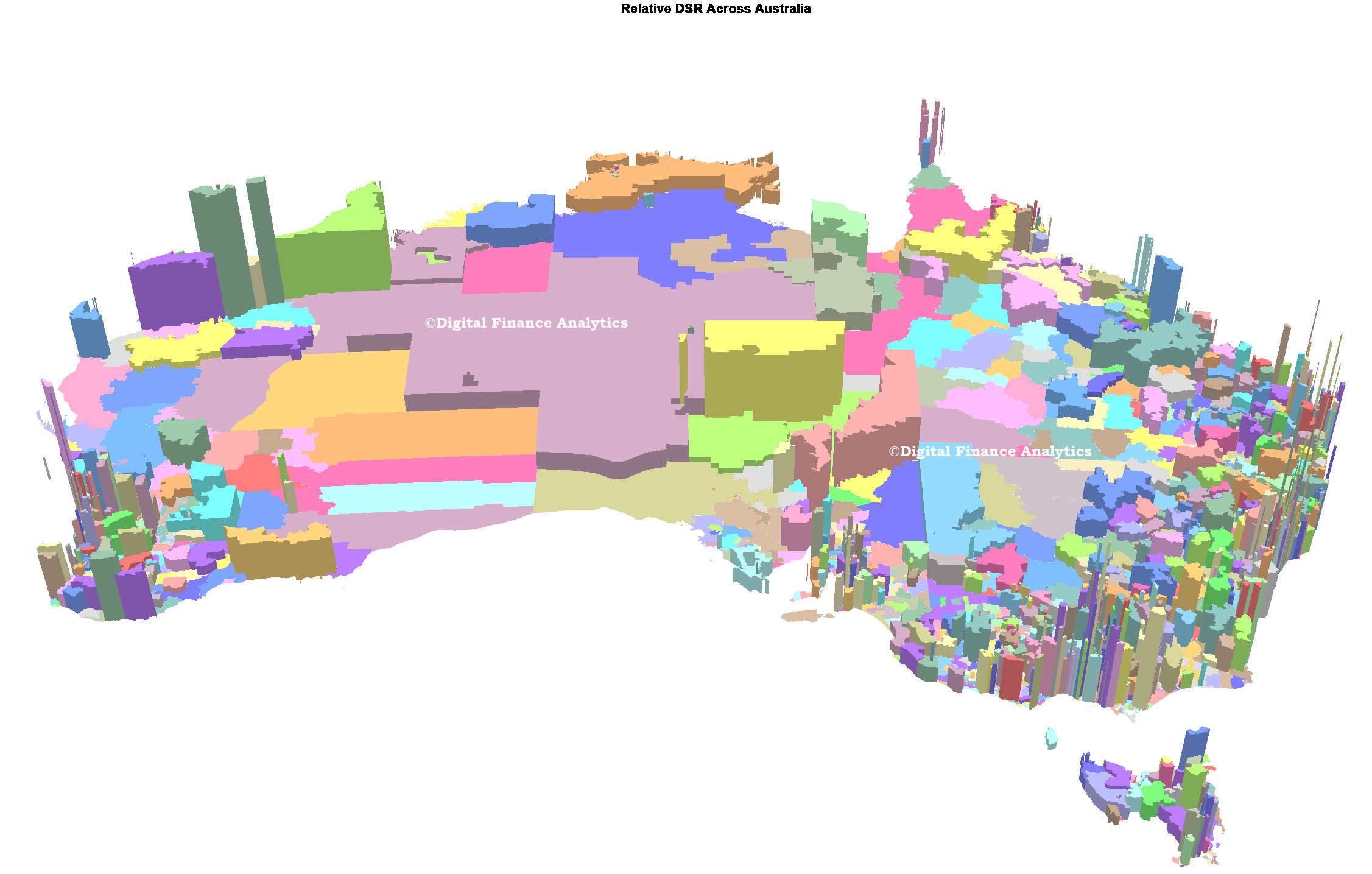

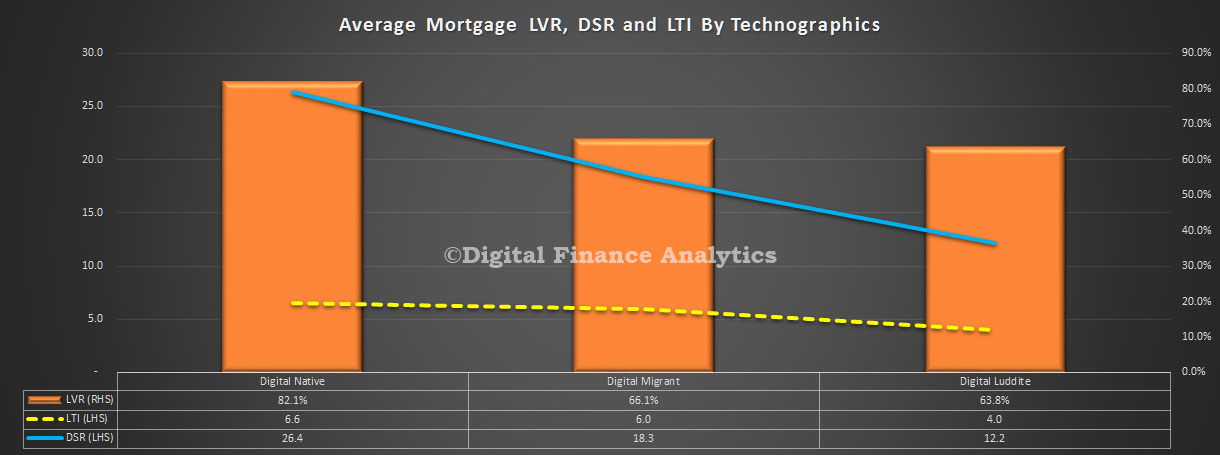

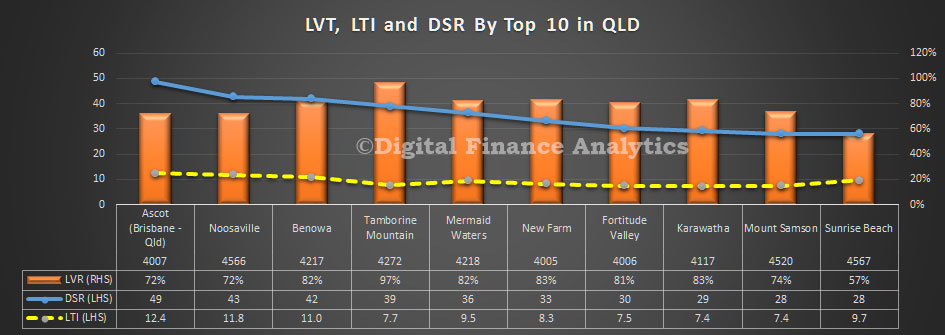

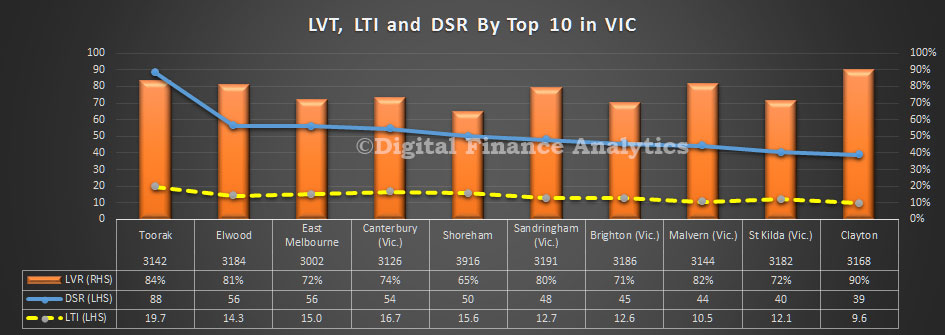

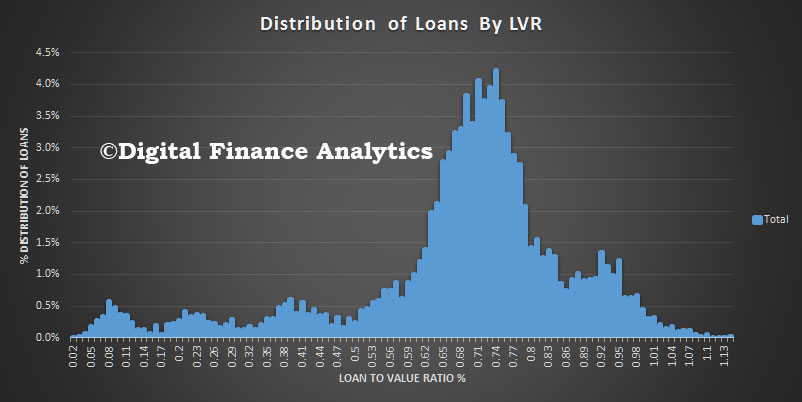

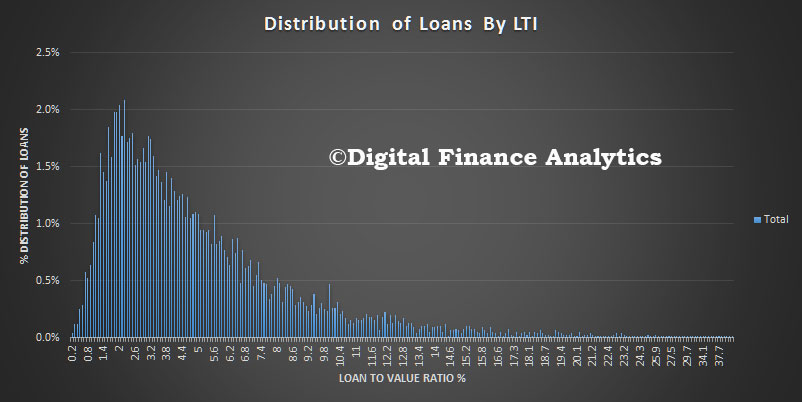

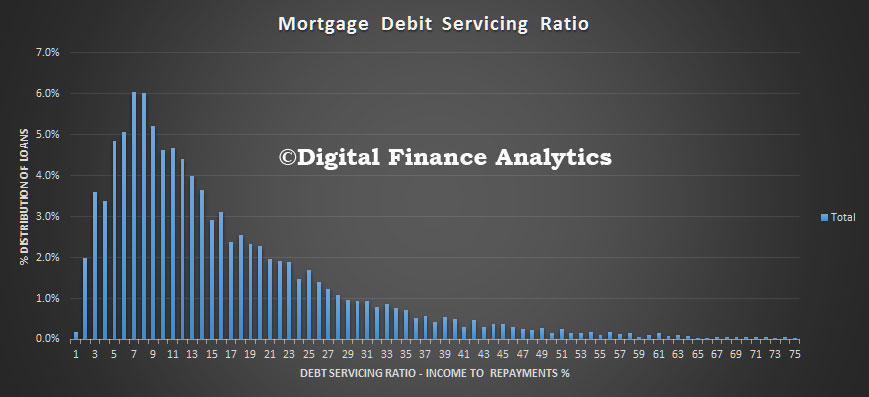

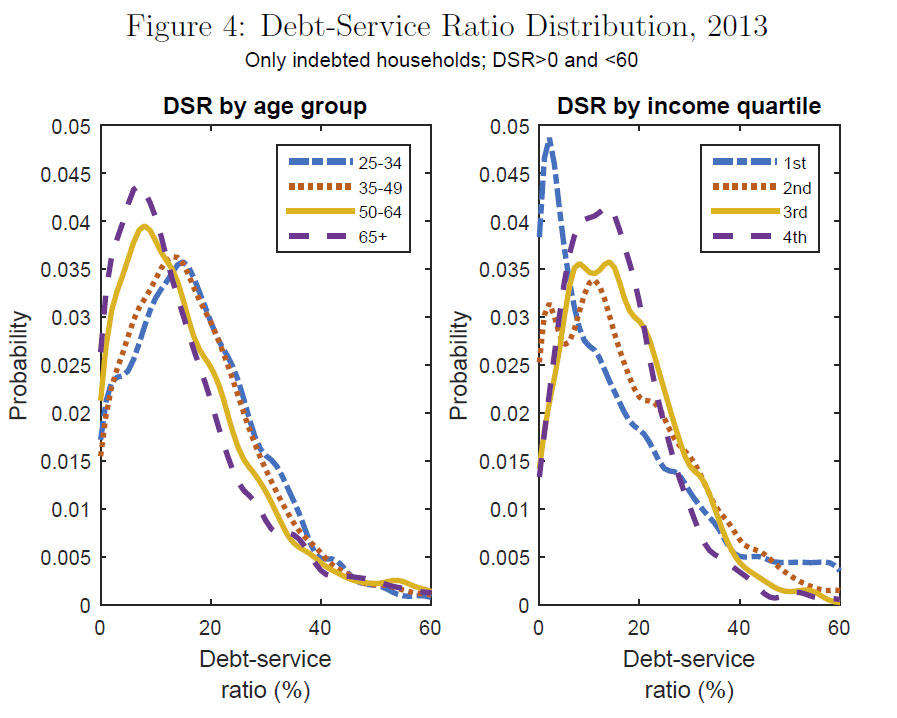

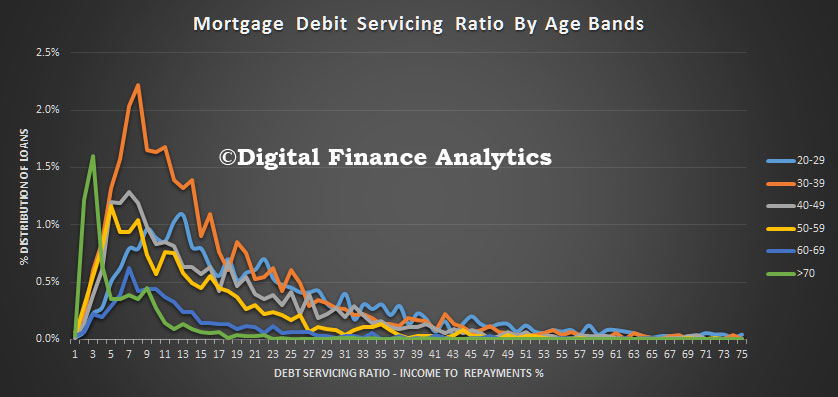

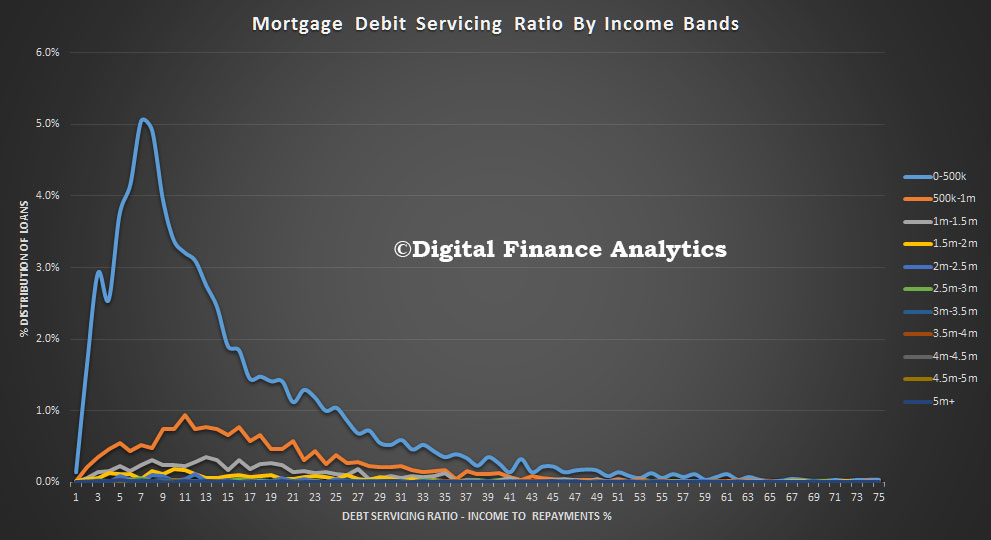

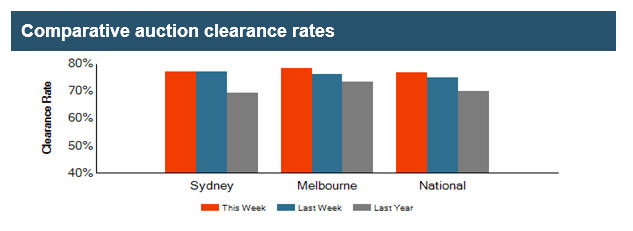

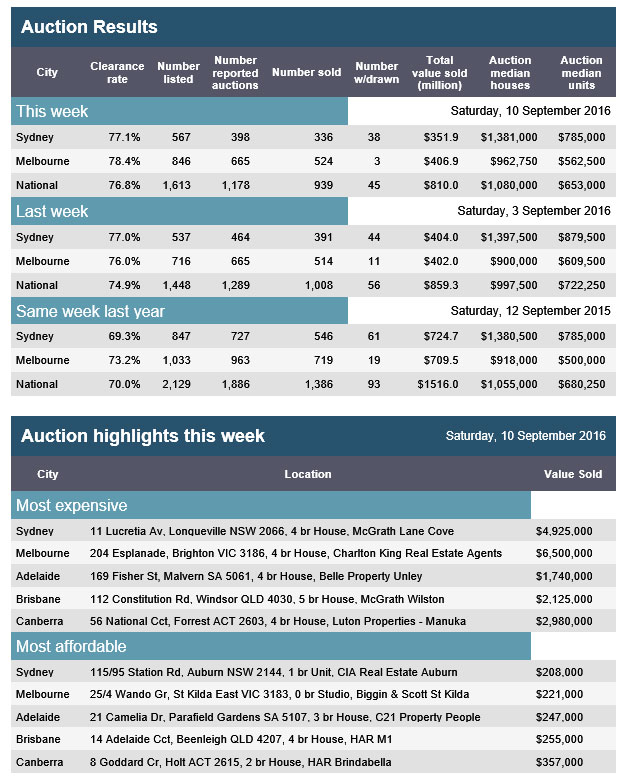

This aligns with the APM data already posted, though there are some variations.

This aligns with the APM data already posted, though there are some variations.