In This Week’s Edition of the Property Imperative we look back over 2017, the year in which the property market turned, focus on the risks to households increased, and banks came under the spotlight as never before.

Welcome the penultimate edition of our weekly property and finance digest for 2017.

Welcome the penultimate edition of our weekly property and finance digest for 2017.

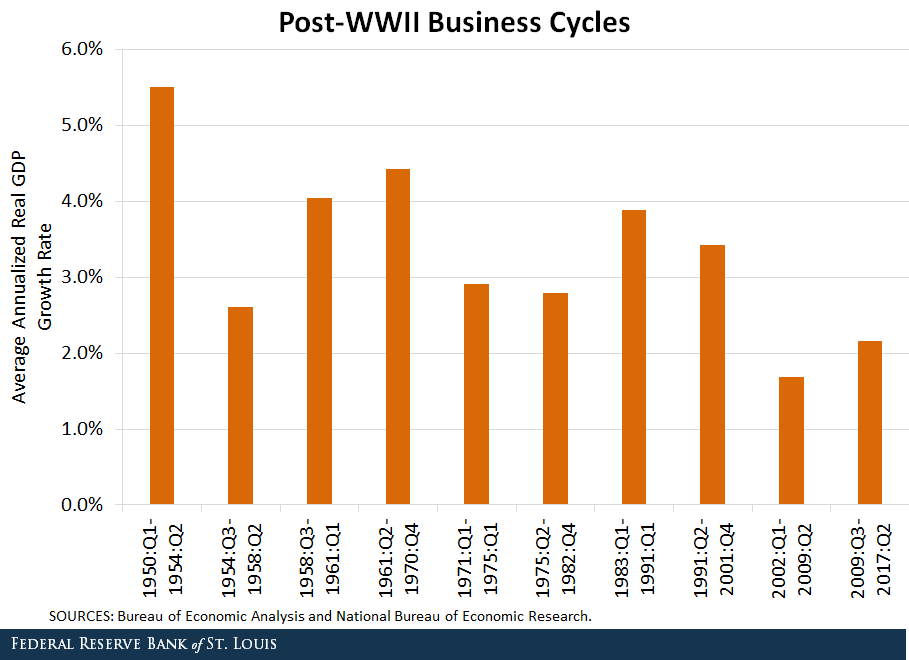

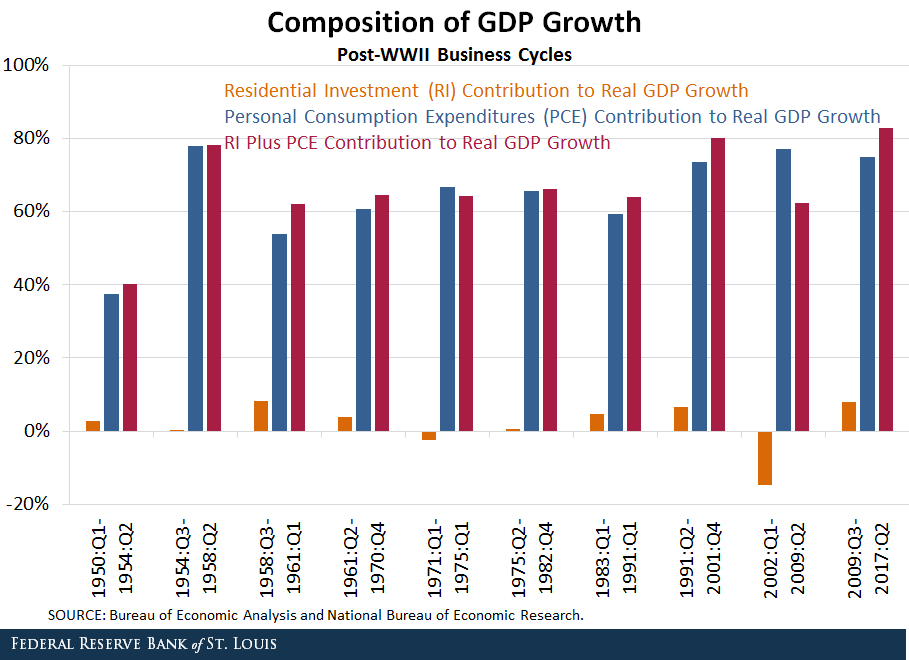

We start with the latest Government budget statement, which came out this week. There was a modest improvement in the fiscal outlook, largely reflecting a boost in tax collections, including from higher corporate profits in the mining sector. But there was also a consumer shaped hole, driven by low wages, lower consumption and lower levels of consumer confidence. Yet, in the outlook, wages are predicted to rise back to 3%, and this supporting above trend GDP growth. This all seems over optimistic to me.

In any case, according to the IMF, GDP is a poor measure of economic progress, with its origins rooted firmly in production and manufacturing. In fact, GDP misrepresents productivity and they say companies that are making huge profits from mining big data have a responsibility to share their data with governments.

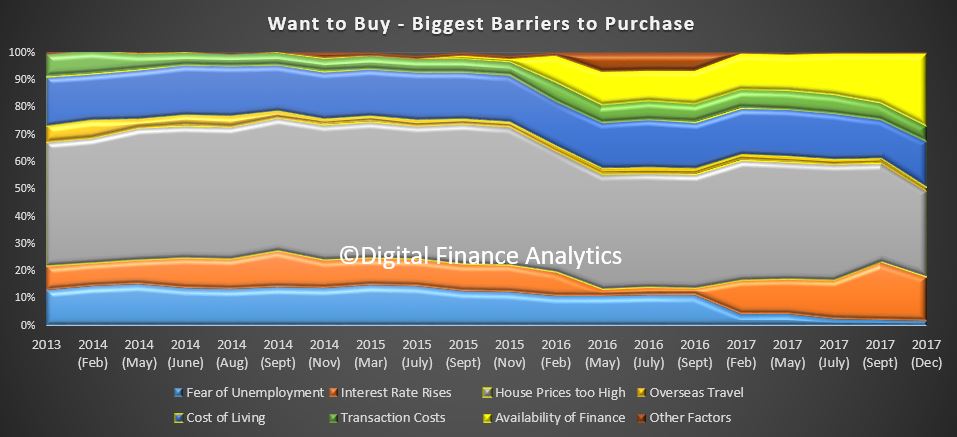

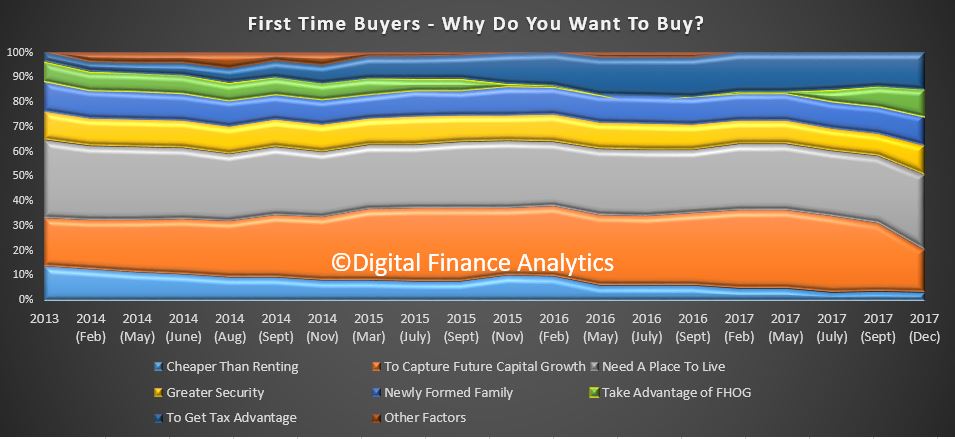

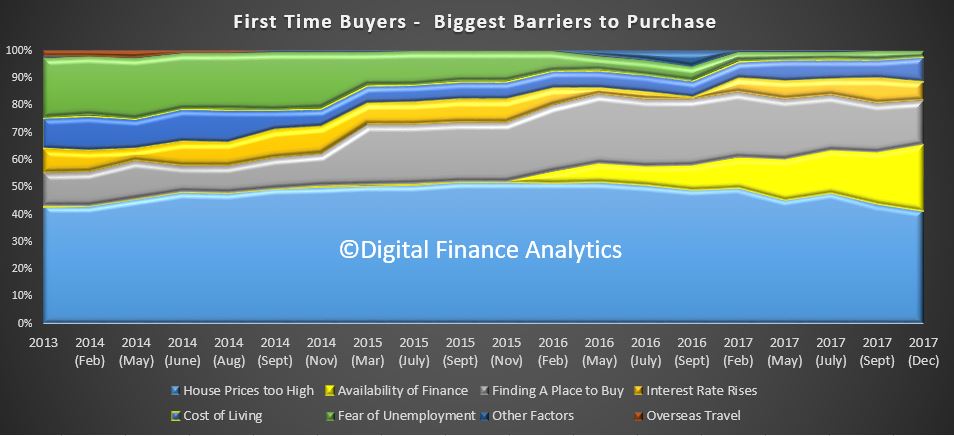

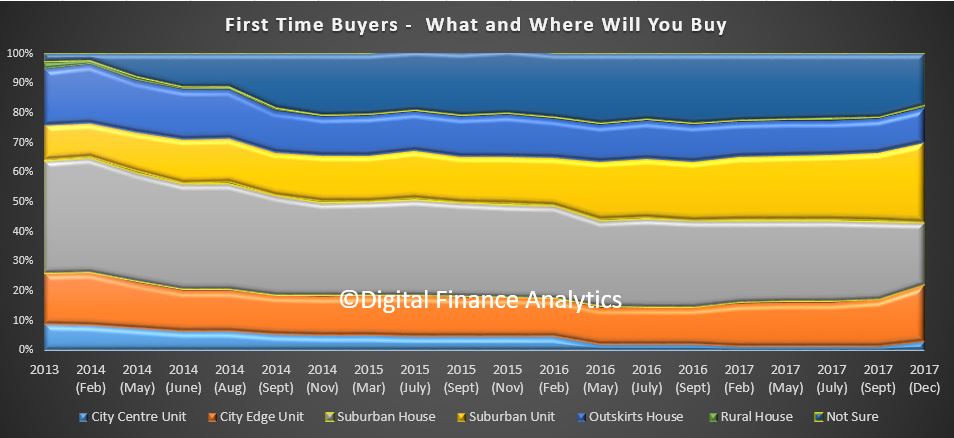

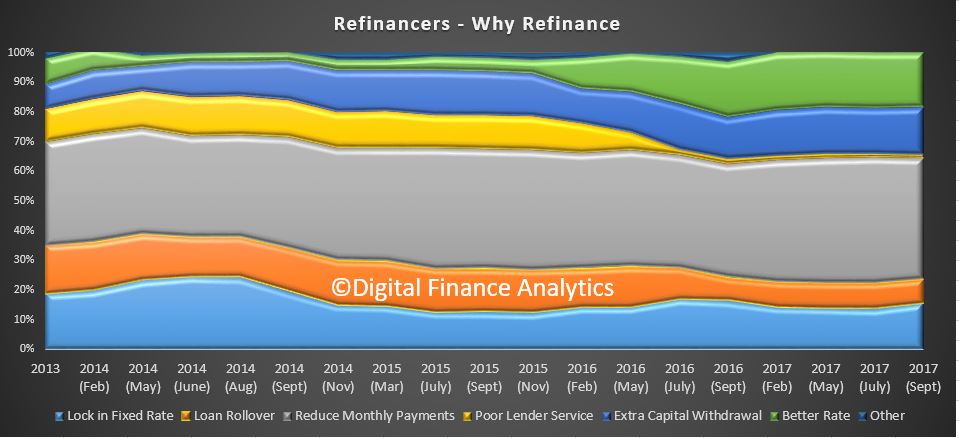

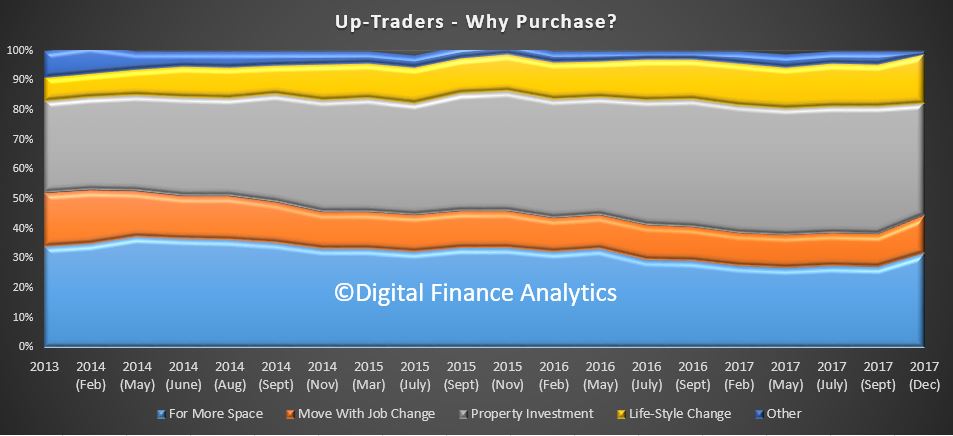

The mortgage industry has seen growth in lending at around 6% though the year, initially led by investors piling into the market, but then following the belated regulatory intervention to slow higher risk interest only lending, momentum has switched to first time buyers, at a time when some foreign buyers are less able to access the market. A third of customers with interest-only mortgages may not properly understand the type of loan they have taken out, which could put many in “substantial” stress when the time comes to pay their debt, UBS analysts have warned. We have also seen a change in mix, as smaller lenders and non-banks (who are not under the same regulatory pressure) have increased their share. AFG’s latest Competition index which came out yesterday, showed that Australia’s major lenders have taken a hit with their market share now down to a post-GFC low of 62.57% of the mortgage market.

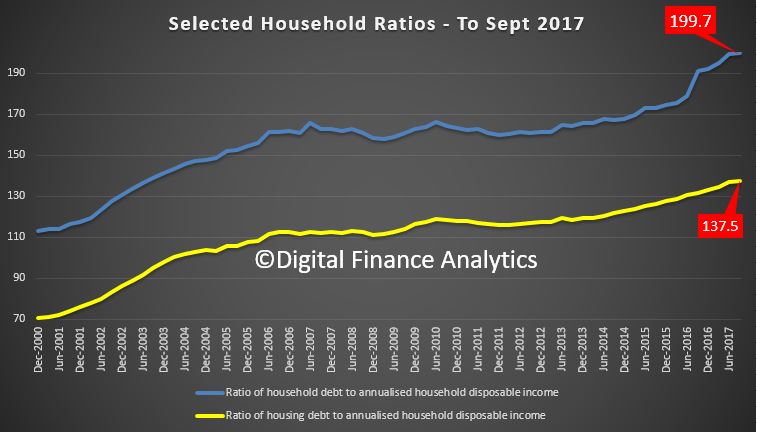

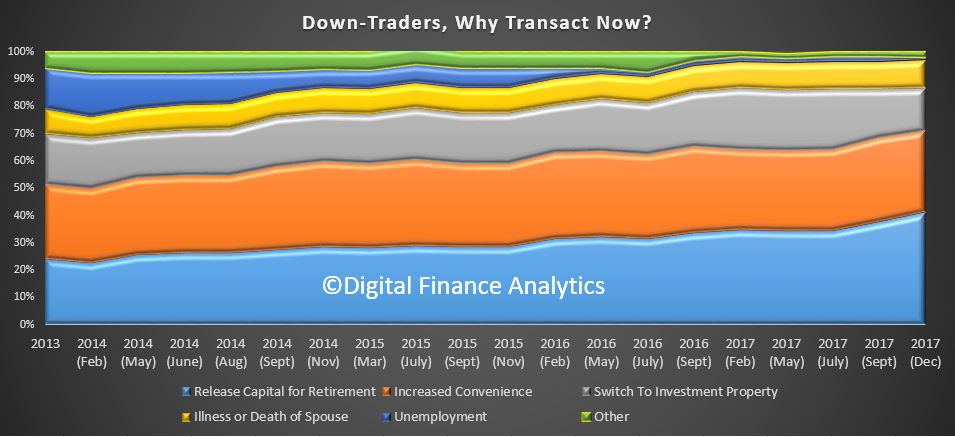

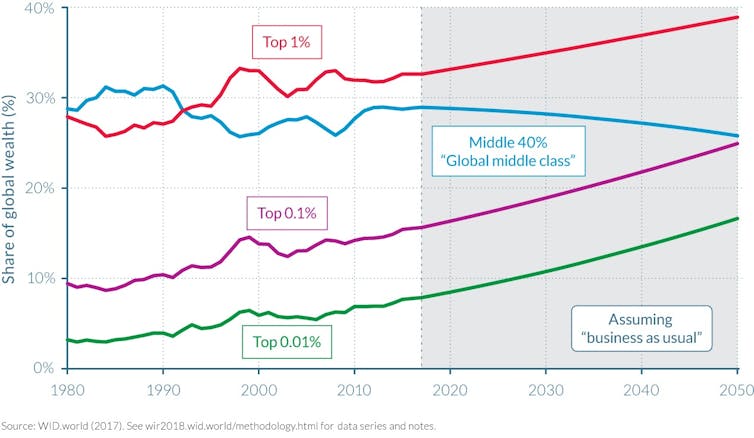

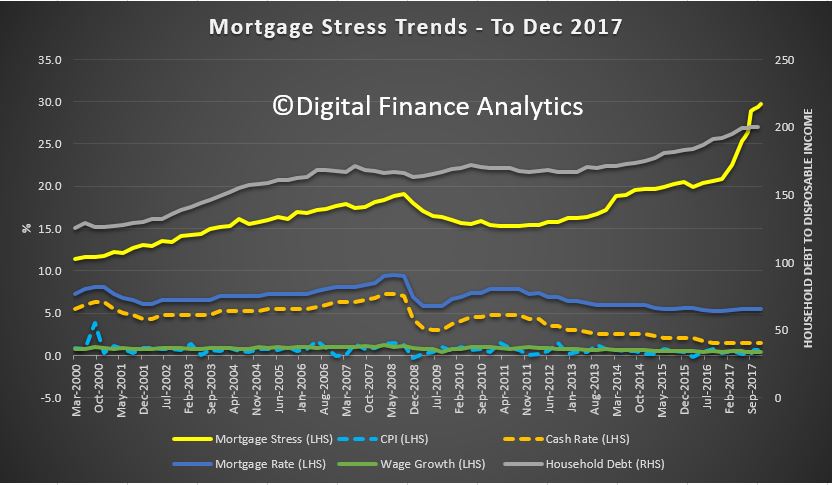

Household finances have been under pressure this year, with income growth, one third the rate of mortgage growth, so the various debt ratios are off the dial – as a nation we have more indebted households than almost anywhere else. This is a long term issue, created by a combination of Government Policy, RBA interest rate settings, the financialisation of property, and the rabid growth of property investors – who hold 35% of mortgages (twice the proportion of the UK). The combination of rising costs of living, and out of cycle rate rises, have put pressure on many households as never before – and we have tracked the rise of mortgage stress through the year to an all-time high.

The latest MLC Wealth Sentiment Survey contained further evidence of the pressure on households and their finances. Being able to save has been a challenge for a number of Australians – almost 1 in 5 of us have been unable to save any of our income in recent years, and for more than 1 in 4 of us only 1-5%. Expectations for future income growth are very conservative – nearly 1 in 3 Australians expect no change in income over the next few years and 15% expect it to fall. Our savings expectations for the future are also very conservative – with more than 1 in 5 Australians believing their savings will fall. The “great Australian dream” of home ownership is still a reality for many, but for some it’s just a dream – fewer than 1 in 10 Australians said they didn’t want to own their own home, but 1 in 4 said home ownership was something they aspired to but did not think it would happen.

Of course the RBA continues on one hand to warm of risks to households, as in the minutes published this week, yet also persists with its line that households can cope, with the massive debt burden, as its skewed towards more wealthy groups. They keep referring to the HILDA survey, which is 3 years old now, as a basis for this assertion. They should take note of a Bank of England Working paper which looked at UK mortgage data in detail, and concluded the surveys tend to understand the true mortgage risks in the market – partly because of the methodology used. They concluded “These results should make policy makers less sanguine about the developments in the UK mortgage market in recent years, which are traditionally analysed using these surveys”.

The latest report from S&P Global Ratings covering securised mortgage pools in Australia to end Oct 2017, showed 30-day delinquency fell to 1.04% in October from 1.08% in September. They attribute part of the decline to a rise in outstanding loan balances during the month, and many older loans in the portfolios (which may not be representative of all mortgages, thanks to the selection criteria for securitised pools). But 90+ defaults remain elevated – at a time when interest rates are rock bottom.

Banks are under the gun, as Government have turned up the pressure this year. There are a range of inquiries in train, from the wide-ranging Banking Royal Commission (which the Government long resisted, but then capitulated), and a notice requiring banks, insurance companies and superannuation funds to detail all cases of misconduct from 2008 onwards has also been issued. The scope includes mortgage brokers and financial advisers. Also the ACCC is looking at mortgage pricing, The Productivity Commission is looking at vertical integration, and we have the BEAR regime which is looking at Banking Executive Behaviour. This week we also got sight of the Enhanced Financial Services Product Design Obligations, and of course the major banks copped the bank tax. There are also a number of cases before the Courts. This week, NAB said it had refunded $1.7 million for overcharging interest on home loans and CommInsure paid $300,000 following ASIC concerns over misleading life insurance advertising

This tightening across the board is a reaction to earlier period of market deregulation, privatisation and sector growth. But at its heart, the issue is a cultural one, where banks are primary focussing on shareholder returns (as a company that is their job), but at the expense of their customers. Even now, the decks are stacked against customers, and the newly revised banking code of conduct won’t do much. We think the Open Banking Initiative will eventually help to lift competition, and force prices lower. But, after many years of easy money, banks are having to work a lot harder, and with much more lead in the saddle bag. Meantime, it is costing Australia INC. dear.

More significantly, the revised Basel rules, though watered down, still tilts the playing field towards mortgage lending, and makes productive lending to business less attractive. Also there is more to do on bank stress testing according to the Basel Committee. The regulation framework is in our view faulty.

One question worth considering, as the USA and other Central Banks lift their base cash rates, is whether there is really a “lower neutral rate” now. Some, in a BIS working paper have argued that Central Banker’s monetary policy have driven real interest rates lower, rather than demographics. But another working paper, this time from the Bank of England, comes down on the other side of the argument. The paper “Demographic trends and the real interest rate” says two-thirds of the fall in rates is attributable to demographic changes (in which case Central Bankers are responding, not leading rates lower). In fact, pressure towards even lower rates will continue to increase. This is a fundamentally important question to answer. We suspect the role of Central Bankers in driving rates is less significant than many suspect, and structural changes are afoot.

Rates in Australia have stayed low this year, at 1.5%, despite the RBA saying this is below the neutral setting, and we expect the bank to move later in 2018, upwards. The rate of rise is now expected to be lower than a year ago, but the international pressure will be up. In addition, the US tax reforms will likely switch more investment to the US, and so banks, who rely on international funding, will likely have to pay more. So we still expect real rates to go higher ahead, creating more pressure on households. Also, of course as rates rise, the costs of Governments running deficits rises, something which will be a drag on the budget later.

Home prices continued to rise through 2017 in the eastern states, while in NT and WA they fell. Recent corrections in Sydney may be an indication of what is ahead in the Melbourne market too. Demand remains strong, but lending standards have been tightened, and investors are getting more concerned about future capital appreciation. This year building approvals were still pretty strong, in line with firm population growth. As an aside, an OECD report this week said that Australian property may well be a target for money laundering, and more needs to be done to address this issue. Auction volumes continue to slide, and we have seen a significant fall in recent weeks.

So, this year we have seen changes in the financial services landscape, the property market is on the turn, and household’s debt levels are rising, creating financial stress for many. As a result, we expect many to spend less this Christmas.

Next time we will discuss the likely trajectory through 2018, but we wanted to wish all our followers a peaceful and restful holiday season. We have really appreciated all the interest in our work – through the year we have more than doubled our readership, thanks to you.

Many thanks for watching. Check back next week for our views on what 2018 may bring.

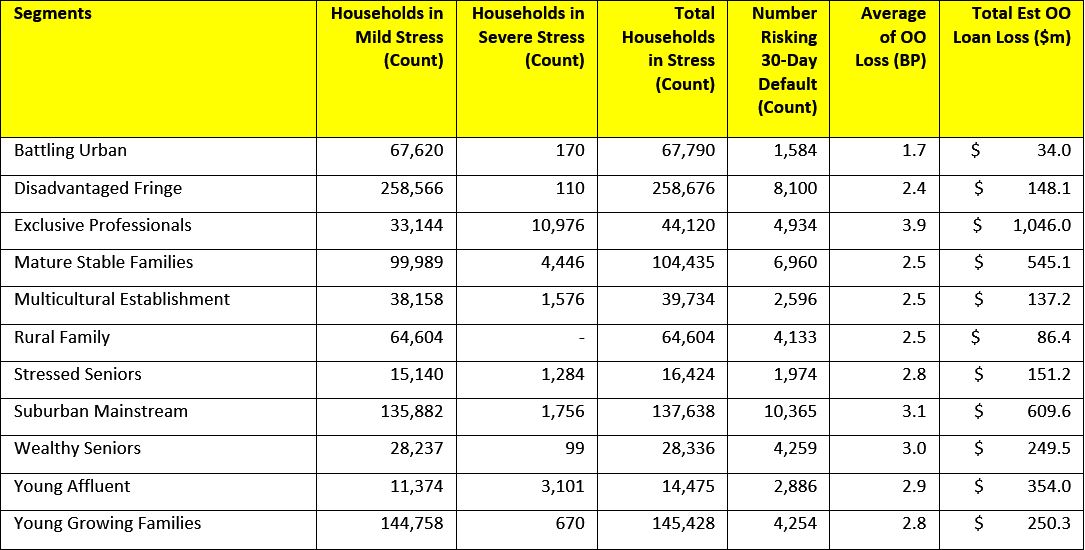

Martin North, Principal of Digital Finance Analytics said “the number of households impacted are economically significant, especially as household debt continues to climb to new record levels. Mortgage lending is still growing at three times income. This is not sustainable”. The latest household debt to income ratio is now at a record 199.7.[1]

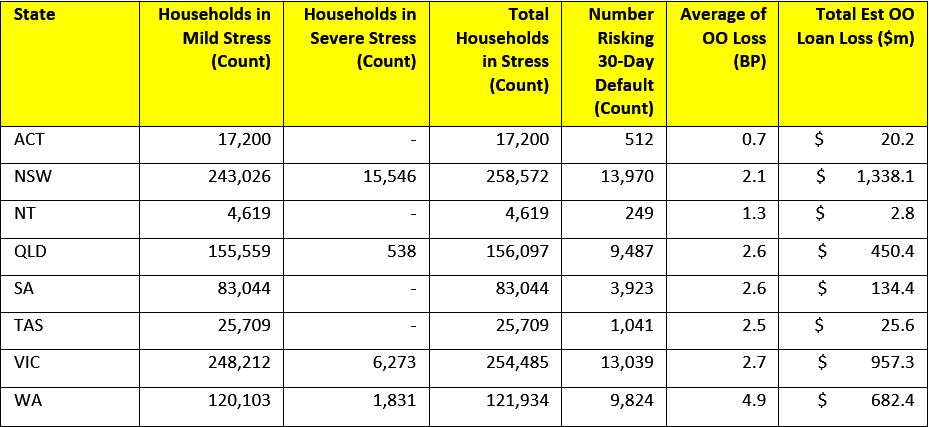

Martin North, Principal of Digital Finance Analytics said “the number of households impacted are economically significant, especially as household debt continues to climb to new record levels. Mortgage lending is still growing at three times income. This is not sustainable”. The latest household debt to income ratio is now at a record 199.7.[1] The largest financial losses relating to bank write-offs reside in NSW ($1.3 billion) from Owner Occupied borrowers) and VIC ($957 million) from Owner Occupied Borrowers, which equates to 2.1 and 2.7 basis points respectively. Losses are likely to be highest in WA at 4.9 basis points, which equates to $682 million from Owner Occupied borrowers.

The largest financial losses relating to bank write-offs reside in NSW ($1.3 billion) from Owner Occupied borrowers) and VIC ($957 million) from Owner Occupied Borrowers, which equates to 2.1 and 2.7 basis points respectively. Losses are likely to be highest in WA at 4.9 basis points, which equates to $682 million from Owner Occupied borrowers.