From The US On The Economy Blog.

For families who are struggling financially, there are times when it is better to keep some cash on hand, even if they hold high-interest debt.

A recent In the Balance article highlights the importance of emergency savings to the financial stability of struggling households. It was authored by Emily Gallagher, a visiting scholar at the St. Louis Fed’s Center for Household Financial Stability, and Jorge Sabat, a research fellow at the Center for Social Development at Washington University in St. Louis.

The Struggle to Make Ends Meet

Many families continue to struggle to make ends meet, the authors said, noting a recent Federal Reserve survey that estimated that almost half of U.S. households could not easily handle an emergency expense of just $400.

Given this, they asked: “Should more families be encouraged to hold a liquidity buffer even if it means incurring more debt in the short-term?”

In explaining why it might make sense, for example, to keep $1,000 in a low-earning bank account while owing $2,000 on a high-interest-rate credit card, Gallagher and Sabat’s research suggests this type of cash buffer greatly reduces the risk that a family will:

- Miss a rent, mortgage or recurring bill payment

- Be unable to afford enough food to eat

- Be forced to skip needed medical care within the next six months

Linking Balance Sheets and Financial Hardship

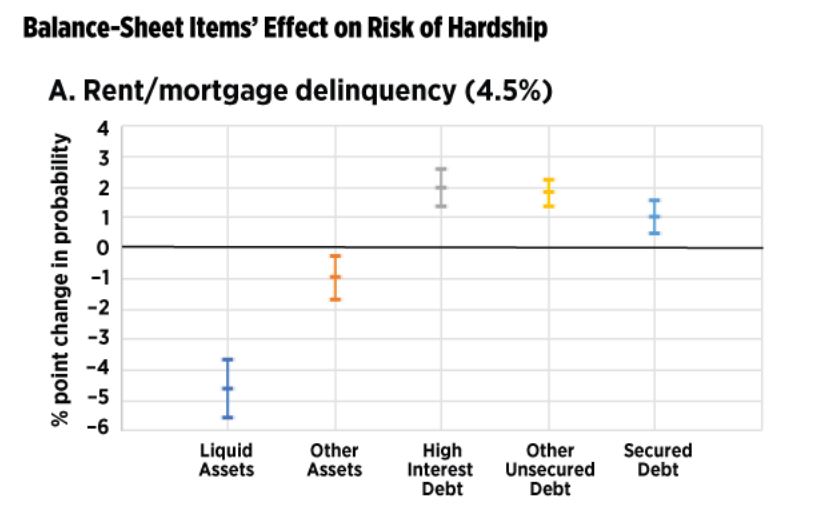

Gallagher and Sabat investigated which types of assets and liabilities predicted whether a household would experience financial hardship over a six-month period.

Their survey encompassed detailed financial and demographic results that covered two time-period observations for the same household: one at tax time, and the other six months after tax time.

“This feature of our data set is ideal for capturing the probability that a household that is currently financially stable falls into financial hardship in the near term,” the authors explained. “Furthermore, the survey samples only from low-to-middle income households, our population of interest for understanding the antecedents of financial hardship.”

They tracked families in the first survey who said they hadn’t recently experienced any of these four main types of financial hardship:

- Delinquency on rent or mortgage payments

- Delinquency on regular bills, such as utility bills

- Skipped medical care

- Food hardship (going without needed food)

Gallagher and Sabat also asked if the family had any balances in:

- Liquid assets, such as checking and saving accounts, money market funds and prepaid cards

- Other assets, including businesses, real estate, retirement or education savings accounts

- High-interest debt, such as that from credit cards or payday loans

- Other unsecured debt, such as student loans, unpaid bills and overdrafts

- Secured debt, including mortgages or debts secured by businesses, farms or vehicles

Controlling for factors such as income and demographics, they then tracked whether the 5,000 families in the survey had suffered a financial shock that would affect the results.

Cash on Hand Matters Most

The authors found that having liquid assets or other assets always predicted lower risk of encountering hardship of any kind, while having debts generally increased the risk of hardship.

Liquid assets had the most predictive power, Gallagher and Sabat said. They noted that a $100 increase (from a mean of $6) was associated with a 4.6 percentage point reduction in a household’s probability of rent or mortgage delinquency.

Liquid assets also significantly reduced the likelihood of entering into more common forms of hardship. A $100 increase in liquidity was associated with declines in the rates of:

- Regular bill delinquency (by 8.3 percentage points)

- Skipped medical care (by 6.3 percentage points)

- Food hardship (by 5.2 percent percentage points)

“These estimated effects are substantial relative to the probability of encountering each hardship,” they said.

Conclusion

“Our findings suggest that households should be encouraged to maintain at least a small buffer of liquid savings, even if the cash in that buffer is not being used to pay down high-interest debt,” Gallagher and Sabat concluded.