In her final speech as Deputy Governor for Markets and Banking, before becoming Director of the London School of Economics, Minouche Shafik sets out an agenda for rebuilding the trustworthiness of experts. She says, “getting this right is vital for determining whether our futures are shaped by ignorance and narrow-mindedness, or by knowledge and informed debate”.

Addressing the Oxford Union, Minouche explores the backlash against experts after the financial crisis, Eurozone crisis, Brexit, and election surprises. As well as being seen to have “got it wrong”, the growing influence of social media and online news has made experts just one of many voices in a cacophony. “A person like yourself” is now seen as credible as an academic or technical expert, and far more credible than a CEO or politician.

However, the application of expert knowledge has improved life expectancy, tackled diseases, and reduced poverty. These achievements have led to many decisions being delegated to experts deliberately insulated from the political process, including the creation of independent central banks as a means to maintain low and stable inflation. Minouche stresses, however, the importance of experts being subject to challenge and rigorous processes to differentiate quality and reduce the risk of getting it wrong.

The changing landscape of information, opinion and trust

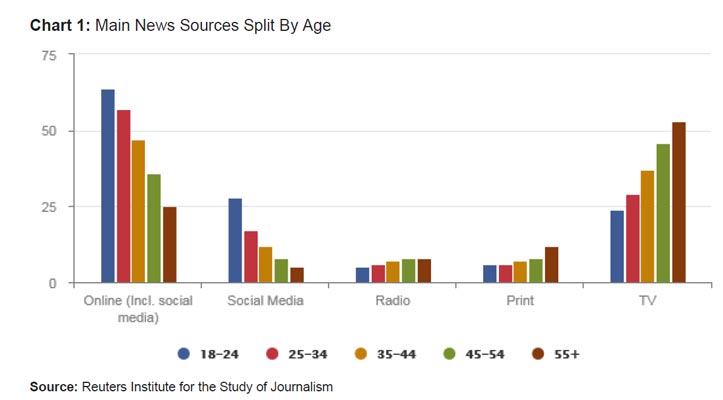

The digitization of freely available knowledge has been hugely democratizing and empowering. Young people are particularly reliant on social media, with 28% of 18-24 year olds saying it is their main source of news, putting it ahead of television.

But there has been a downside – “people can be overwhelmed with information that is difficult to verify, algorithms create echo chambers of the like-minded who are never challenged; fake news distorts reality; “post-truth” fosters cynicism; anonymity bestows irresponsible power onto individuals who can abuse it; a world in which more clicks means more revenue rewards the most shrill voices and promotes extreme views,” Minouche argues.

But there has been a downside – “people can be overwhelmed with information that is difficult to verify, algorithms create echo chambers of the like-minded who are never challenged; fake news distorts reality; “post-truth” fosters cynicism; anonymity bestows irresponsible power onto individuals who can abuse it; a world in which more clicks means more revenue rewards the most shrill voices and promotes extreme views,” Minouche argues.

All releases are available online at www.bankofengland.co.uk/news 2

We need expertise more than ever. But confidence in experts is at an all-time low. Transparency is not good enough if information is inaccessible and “unassessible”. Instead, we should focus more on increasing trustworthiness.

An agenda for rebuilding trustworthiness

Societies can set standards and empower individuals to assess trustworthiness for themselves. There are many elements to such an agenda:

- Experts should embrace uncertainty – Minouche argues that “rather than pretending to be certain and risk frequently getting it wrong, being candid about uncertainty will over the long term build the credibility of experts.” Coupled with the need to get their often complex messages across in today’s shortform world, this means “the modern challenge for experts is how to communicate with brevity, but without bravado.”

- Good practices often found in academia (like declaring conflicts of interest, peer review, and publishing underlying data and funding sources) need to become more widespread to the world of think tanks, websites and the media.

- Consumers of expertise need better tools to assess quality – Minouche highlights the importance of people being given the tools to “differentiate facts from falsehood”. The e-commerce world has developed an array of tools to help consumers determine quality. We need something similar for the world of ideas. Good examples are the growth of fact-checking, authoritative websites and the FICC Markets Standards Board, which are designed to enhance trustworthiness in areas where trust has been eroded.

- Listen to the other side – Minouche states that “we can all make an effort to engage with views that are different from our own and resist algorithmic channeling into an echo chamber.”

- Manage the boundary between technocracy and democracy carefully – Minouche stresses that “technocracy can only ever derive its authority from democracy.” And for that reason there must always be clarity about the boundaries and accountabilities between experts and politicians.

Minouche concludes, “so what have the experts ever done for us? The application of knowledge and the cumulation of that through education and dissemination through various media and institutions are integral to human progress. So the challenge is not how to manage without experts, but how to ensure that there are mechanisms in place to ensure they are trustworthy.”