Treasurer Scott Morrison continues to warn about the decline of Australia’s global competitiveness if the centrepiece of the 2016–17 federal budget – a company tax rate cut – is not passed.

However, such tax cuts are not necessarily the best approach for the government to support small business. They need other – more immediate – forms of support, our research shows.

However, such tax cuts are not necessarily the best approach for the government to support small business. They need other – more immediate – forms of support, our research shows.

What’s being proposed?

The 2016-17 budget reflected the Turnbull government’s catchphrase of “jobs and growth”. From a small-business perspective, the budget wanted to:

… boost new investment, create and support jobs and increase real wages, starting with tax cuts for small and medium-sized enterprises, that will permanently increase the size of the economy by just over 1% in the long term.

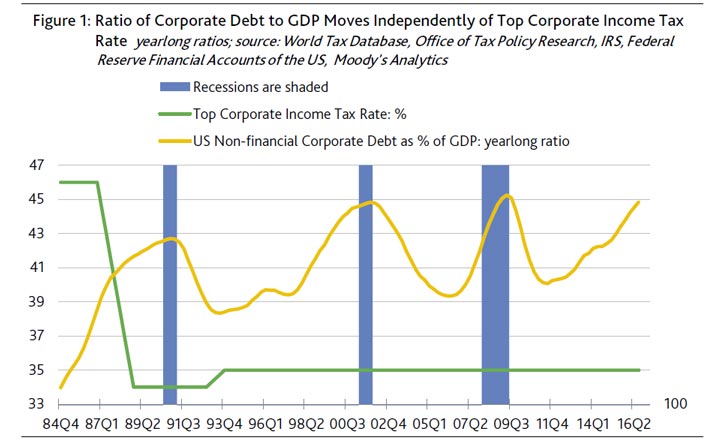

In 2014, Australia had the fifth-highest company tax rate among OECD countries, albeit average in the Asia-Pacific region. Local investors benefit from lower taxes on dividends through Australia’s dividend imputation system, which passes credits onto them for corporate taxes already paid.

The Abbott government later succeeded in lowering the tax rate for small businesses with a turnover of less than A$2 million from 30% to 28.5%. The Turnbull government’s plan would eventually reduce the rate for all companies to 25% by 2026-27. It’s a phased implementation over the next ten years, starting with an immediate cut for small companies to 27.5%.

However, 70% of small businesses are unincorporated. This means their owners add profits to their personal income for tax purposes. While the government has promised an increase in their tax offset percentage, it plans to retain the cap of A$1,000.

All small businesses will benefit from the simplification of tax rules for stock, GST and depreciation. But the government’s plan introduces three levels of concessions for small businesses. This complicates the definition of what these small businesses are.

Definition disputes

Defining small business goes beyond an academic debate.

With little consensus on typical turnover numbers – these range from A$2 million to A$25 million – a better indicator could be the Australian Bureau of Statistics definition of small businesses as those with fewer than 20 employees. And 97% of the 2.1 million businesses trading in Australia fit this definition.

It is risky, though, to simplify the definition into one blunt instrument that ignores differences in industry, life cycle and high-volume versus high-worth sales. A more nuanced approach is needed to ensure relief for the businesses that need it most.

However, the major political parties seemingly remain focused on turnover as a measure of what is and isn’t a small business. The government’s plan extends the upper limit for the turnover of small businesses to A$10 million by 2016–17, which covers some of the 3% of Australia’s non-small businesses.

Meanwhile, Labor has argued for immediate support for tax cuts to small businesses with a turnover of less than A$2 million.

Lifting the turnover threshold for all small businesses from A$2 million to A$10 million in the short term will increase the number of businesses that can access some tax concessions by 90,000. And it may improve economic growth as larger firms receive some relief.

What small businesses actually need

Small businesses need immediate and certain tax relief in the short term. They struggle with an uncertain business environment.

But, in the longer term, our research shows increased competition, a lack of market demand and red tape are but a few of the issues small businesses deal with. They highlighted statutory and regulatory compliance, as well as tax planning and compliance, as major issues for them.

More than tax rates, complex tax requirements and regulations are issues causing small businesses substantial distress. The Australian Tax Office’s research supports this: more than 70% of surveyed clients viewed their tax affairs as complex. And the World Bank’s ease of doing business index ranks Australia 25th in terms of ease of paying taxes.

The immediate tax relief for small businesses is tied up in proposed legislation surrounding the government’s ten-year tax plan, which is unlikely to find enough support to pass the parliament in its current form. The uncertainty and complexity that have ensued from the political conflict over tax have negative effects on the small business landscape.

Innovation is likely to suffer under such uncertain conditions. The government’s plan recognises that:

Small businesses are the home of Australian enterprise and opportunity and they are where many big ideas begin.

In addition to ideas and passion, small businesses need resource availability, appropriate capabilities and market access to innovate. The plan proposes measures that satisfy some of these criteria, but more focus on finding ways to minimise bureaucracy to provide time to focus on innovation is needed.

The role of government is undeniable in such initiatives. Even if one argues that tax relief is a temporary reprieve, this cash injection can jump-start small business innovation and growth.

Should the two major parties fail to find common ground on the government’s company tax cut, the stalemate will continue – and leave small businesses in the lurch.

Authors: Associate Professor in Innovation, The University of Queensland; Lecturer in Tax Law, The University of Queensland.