Housing prices are falling in Sydney and Melbourne, so housing must be becoming more affordable – right?

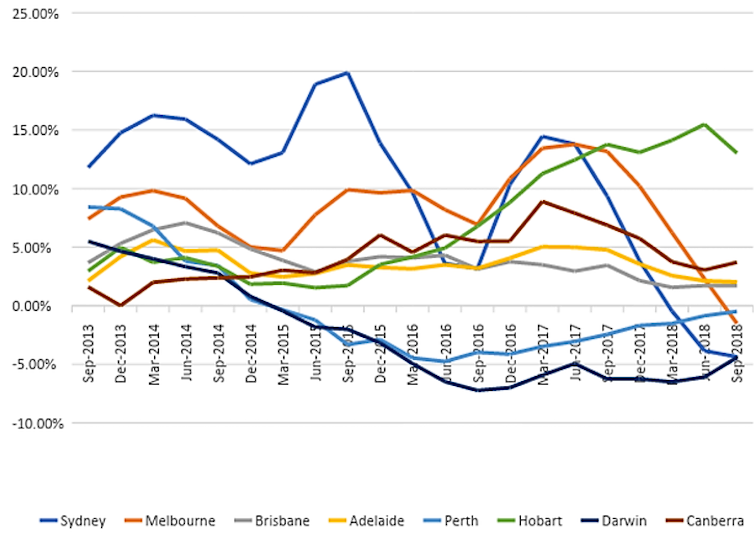

The annual growth of house prices has been slowing consistently for more than a year in Australia’s largest cities. Prices finally started falling in the latter part of last year. The decline began much earlier in Perth and Darwin. Prices in most other cities, with the exception of Hobart, have been more stable.

House owners have a secret weapon

A rise in house prices is a mixed blessing. For those whose employment and savings strategies have helped them become home owners, price inflation is a good thing – the value of the house rises while the mortgage debt stays the same, or falls. For others, the savings and income targets for owning a home become ever more elusive.

So this should mean falling house prices are bad for home owners and good for aspiring home owners, right? In practice, things don’t work out quite like this, for several reasons.

Provided they are financially “liquid” (they have a job and can cope financially), home owners have a secret weapon: they don’t have to sell.

Research shows housing markets tend to operate in periods of “frenzy” alternating with periods of relative inactivity. Lots of people try to capitalise and trade up in a hot market. Once markets cool, people tend to stay where they are and wait for prices to improve.

For aspiring home owners, this is bad news. Although prices might be falling, fewer people are vacating their houses. This reduces the supply of houses on the market at lower prices.

Weaker markets make loans harder to get

House markets adjust to economic cycles, although these adjustments tend to be exaggerated and are prone to overshooting. The global financial crisis is an obvious example of an extreme correction when asset values plummeted.

The current dip in house prices in Australia is almost certainly a milder adjustment. However, even minor adjustments in the housing market are associated with adjustments elsewhere in the economy, particularly in labour markets.

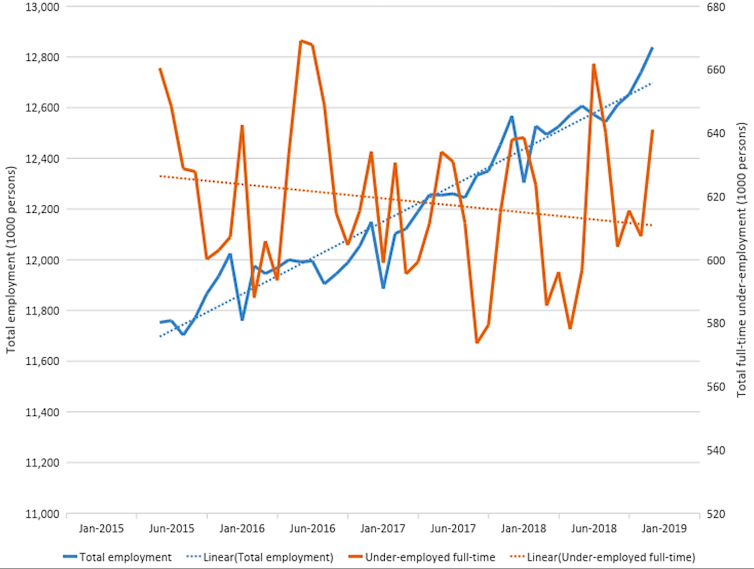

The graph below shows the national trends in employment and underemployment over the past three years. Although total employment has been growing, the reported level of underemployment (a measure of the desire of workers to work more hours than they do) was also growing for much of 2018. Low wages growth and limited working hours do not help when people are already struggling to afford a house.

The supply of finance in mortgage markets also depends on the economic cycle. Unfortunately, falling house prices and a deteriorating economic outlook tend to translate to tighter lending conditions.

So while housing prices might be falling in our biggest cities, at the same time it’s becoming harder to get a home loan. The number of first home buyer dwellings financed fell by more than 5% in the year to November 2018.

So what’s next for the housing market?

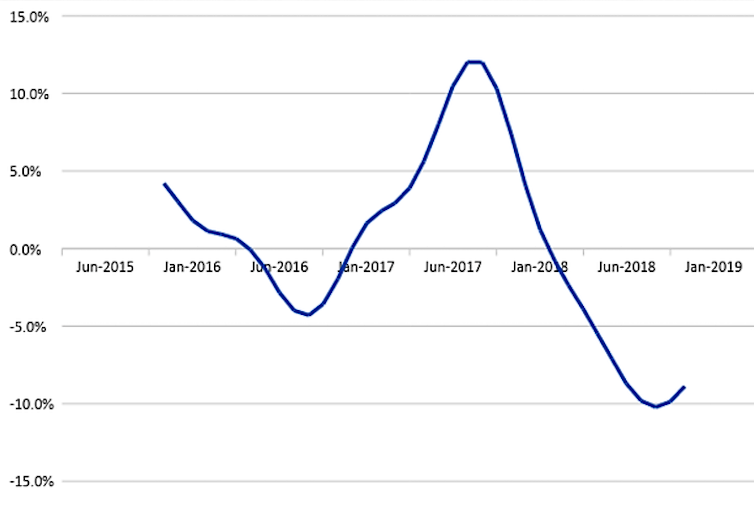

Change in the total number of properties sold is also a useful leading indicator, meaning that transactions data tend to signal a change in market conditions long before average prices begin to change. The chart below shows the year-on-year growth in transactions peaked in the third quarter of 2017.

The growth in transactions began slowing, then became negative in the early months of 2018. These changes occurred much earlier than the plateau, then fall, in prices in late 2018.

The outlook is never certain, but it is worth noting that prices very rarely stabilise or begin growing while the transaction volume is still declining.

Like many sectors of the economy, housing markets are cyclical. But what makes the housing market different is the historical fact that periods of falling prices are much less frequent than periods of rising prices. The market will soon return to its long-run unsustainable trajectory of rising prices and declining affordability.

During the current price adjustment, housing affordability may appear to improve slightly. But low wages growth and limited working hours, coupled with lending restrictions, combine to make it just as hard for first home owners to enter the market.

Current circumstances create opportunity elsewhere in the housing system. In particular, modestly falling prices coupled with lenders issuing fewer mortgages to owner-occupiers create fertile conditions for private residential investors. Times like this tend to favour cash buyers rather than those who need to scrape together a deposit and secure a mortgage before they can buy a house.

Paradoxically, then, declining house prices are no better for housing affordability than rising prices.

Author: Chris Leishman, Professor of Housing Economics, University of Adelaide