The Productivity Commission Report into Competition in The Australian Financial System looked specifically at the role and function of the big four banks. Today we look at some of the evidence which they presented, in the light of the Green’s recently released policy on “Breaking Up the Banks”.

Whilst the market dominance of the big four, Westpac, CBA NAB and ANZ does not necessarily in itself mean the market is not competitive, the Productivity Commission suggests that such dominance may allow them to stifle competition by maintaining prices at artificially high levels or limiting innovation without losing any market share.

Whilst the market dominance of the big four, Westpac, CBA NAB and ANZ does not necessarily in itself mean the market is not competitive, the Productivity Commission suggests that such dominance may allow them to stifle competition by maintaining prices at artificially high levels or limiting innovation without losing any market share.

In many banking systems globally, larger institutions have more market power, and Australia is no exception. Their sheer size allows the major banks to spread their fixed costs (such as investment in new IT systems) across a broader asset base. They are also able to grow more quickly, as they have greater capacity to respond to an increase in demand. At the same time, size can create challenges — for example, changes are more difficult to implement in very large systems. There is a tipping point beyond which large organisations are no longer efficient and they operate at declining returns to scale.

The clearest and most powerful advantage that larger banks have over smaller ADIs, and one that gives them substantial market power, is their ability to raise funds at lower costs. Larger banks have better credit ratings, and as a result, investors and depositors are willing to lend them funds at lower rates. In part, these credit ratings can reflect the ability of larger banks to hold more diversified lending portfolios. However, these ratings also benefit from explicit and implicit government guarantees, such as being considered ‘too big to fail’. Their lower costs of funding enable the bigger banks to maintain their profits and offset some of the increases in their costs resulting from regulatory change, which may prove more difficult for smaller institutions.

Larger operators also benefit, to an extent, from integration, which gives them the ability to exert additional control over some markets. Vertical integration allows larger institutions to have more control over the costs of their inputs, while smaller entities rely on third parties to access funding markets and other types of services. In effect, small ADIs compete against the major banks, but also depend on them to access the funds that allow them to continue competing. Cross-product (conglomerate) integration gives the larger institutions the opportunity to cross subsidise some of their products, and also offer consumers an integrated bundle of services, which may help to lock customers into the provider and raise customer switching costs.

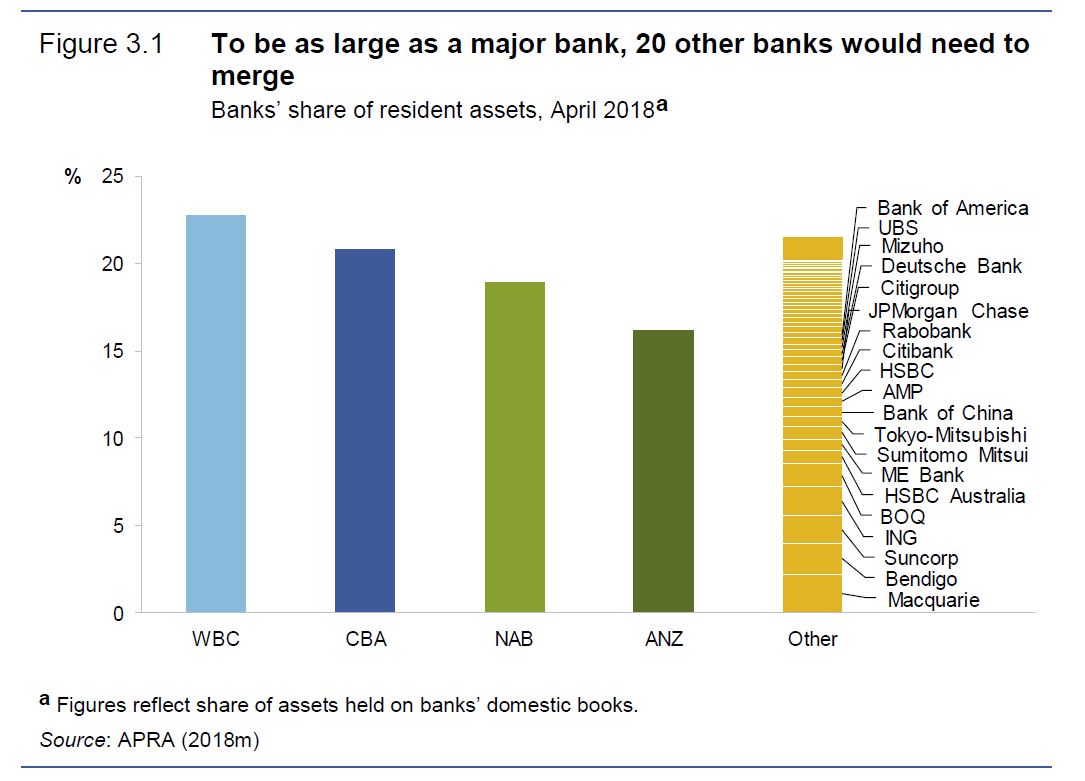

Despite the consolidation of some smaller players, the major banks still maintain substantial market power — because the difference in size between them and the other providers in the market is exceptional. Based on the value of their assets in April 2018, ANZ (the smallest of the majors) was seven times bigger than Macquarie, the next bank by size of assets. Twenty banks (ranking 5th to 24th by size of assets) would need to merge in order to match ANZ. Only if all banks in Australia, other than the big four, merged would they be able to rival the biggest two — Westpac and the CBA.

An important aspect of banks’ size is their geographical reach, either through branches or other distribution networks. In 2017, there were about 5300 bank branches, over 390 credit union branches and 74 building society branches. The major banks accounted for 60% of all branches, and only two other ADIs (Bendigo and Adelaide Bank and Bank of Queensland) had branches in every state and territory. Major banks are also strongly represented in other distribution networks, such as mortgage brokers.

An important aspect of banks’ size is their geographical reach, either through branches or other distribution networks. In 2017, there were about 5300 bank branches, over 390 credit union branches and 74 building society branches. The major banks accounted for 60% of all branches, and only two other ADIs (Bendigo and Adelaide Bank and Bank of Queensland) had branches in every state and territory. Major banks are also strongly represented in other distribution networks, such as mortgage brokers.

At the same time, customer satisfaction levels reported by individual banks, including the major banks, remains high. While consumers may be disillusioned with the banking system, it seems they are satisfied with their chosen institution. Of course, consumers may not always be aware of the alternative services and prices available from other institutions — or even their own institution — that may be more suitable for their circumstances.

Australia’s major banks have some of the strongest business brands in our economy. Industry estimates put the value of their brands between $6 and $8 billion, with CBA having the highest brand value. Their public image has been affected by a series of scandals and the continued community perception that they do not operate in their customers’ best interests

The major banks benefit from the perception that they are safe, stable institutions, and that the government will step in to help them if needed. This supports their existing market power, and in some cases increases it further — during the global financial crisis (GFC), consumers transferred some of their savings to the major banks, as they were perceived as safer. Even when no financial crisis looms, small institutions may find it difficult to attract consumers from rivals that are perceived as safer. This is despite the fact that retail deposits benefit from the same government guarantee, regardless of ADI size.

Consumer behaviour may also contribute to market power; the low levels of consumer switching and a general disengagement from financial services help ADIs maintain their position in the market, and make it harder for new competitors to gain any significant market share.

The major banks benefit from a substantial asset base and stable market shares, which give them the ability to cope more easily with regulatory change, while also investing and innovating — which in turn can contribute further to their market power. Small institutions argue that their regulatory burden is disproportionately large. For some, the pace and extent of regulatory change has left them limited resources to increase market share.

Measures introduced by the Australian Government and APRA are intended, in part, to offset the cost advantages of large banks — examples include the major bank levy and potentially the specific prudential regulation imposed on domestically significant banks, which applies to the big four banks. It has been argued by Government that when such regulations raise the costs of the major banks, they may help smaller competitors.

But the PC says the objective of competition policy is not to assist some competitors by adding burdens to others, but rather to have the least necessary intervention that is consistent with allowing choice and innovation to meet consumer interests in an efficient manner. Viewed simply, to raise the cost of businesses that have market power — while doing nothing to address adverse use of that market power — risks seeing those costs imposed on customers.

They conclude that the major banks benefit from advantages of scale, scope and branding which give them substantial market power and the ability to remain broadly insulated from competitive threats posed by smaller incumbents or new entrants. They concluded that this balance of power gives the major banks the ability to pass on cost increases and set prices that maintain high levels of profitability — without losing market share.

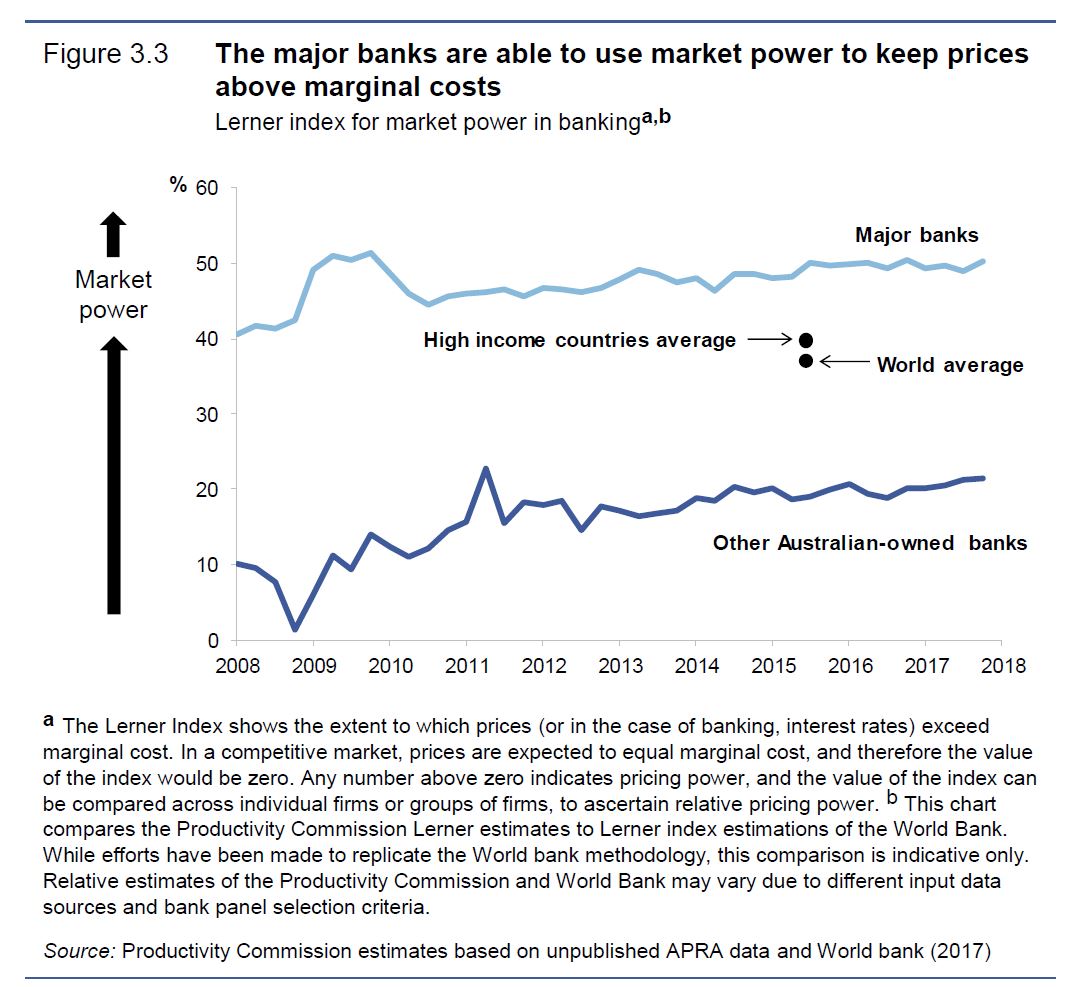

While high concentration on its own is not necessarily indicative of market power resulting in inefficient pricing or (tacitly collusive) oligopolistic behaviour and the major banks have all argued that vigorous competition in the banking system is evident in a number of market outcomes, their analysis shows that major banks are the dominant force in the market. As a result, they are able to charge higher premiums above their marginal costs, compared with other institutions. Approximately half of the loan price that major banks charge is a premium over the marginal cost — double the margin that other Australian-owned banks have.

In fact, they say, over the past five years, changes to prudential regulations have increased the cost of funding for the major banks. However, and as has been anticipated by regulators, they have been able to recoup these higher costs by increasing interest rates for borrowers. According to the ACCC, the big four banks tend to disregard the pricing decisions of smaller lenders — rather, they focus on the expected reactions of the other majors and any changes they may make to interest rates. As a result, each of the banks examined by the ACCC ‘generally aim to set their headline variable rates to broadly align with the big four banks’ . The major banks view this behaviour as an attempt to compete and maximise their profits — but the end result from a consumer point of view is non-competitive pricing. The lack of price competition is reinforced by obfuscation. The prices that ADIs advertise are often not indicative of what consumers actually pay, as we discussed the other day.

In fact, they say, over the past five years, changes to prudential regulations have increased the cost of funding for the major banks. However, and as has been anticipated by regulators, they have been able to recoup these higher costs by increasing interest rates for borrowers. According to the ACCC, the big four banks tend to disregard the pricing decisions of smaller lenders — rather, they focus on the expected reactions of the other majors and any changes they may make to interest rates. As a result, each of the banks examined by the ACCC ‘generally aim to set their headline variable rates to broadly align with the big four banks’ . The major banks view this behaviour as an attempt to compete and maximise their profits — but the end result from a consumer point of view is non-competitive pricing. The lack of price competition is reinforced by obfuscation. The prices that ADIs advertise are often not indicative of what consumers actually pay, as we discussed the other day.

The PC concludes that oligopoly behaviour and the ability to use market power adversely are evident Indeed, the major banks themselves are unable to identify competitive threats in the domestic markets, and they focus on large technology companies overseas as their future potential competitors. Such threats have yet to eventuate, and will in any event need to exist in the regulated environment that consciously limits rivalrous behaviour. Whilst the ‘tail’ of smaller providers aims primarily to match the major banks in their pricing, they are subject to similar or, at times, more costly regulation and do not benefit from the funding or efficiency advantages of the major banks, so they are often unable to offer prices that are substantially lower. Some of the smaller banks, in particular foreign institutions, operate in niche markets (such as agribusiness) where they can potentially benefit from specialisation and set prices that reflect their capacity to price discriminate. Others, such as credit unions and other mutually owned institutions, are consolidating in order to benefit from economies of scale. But in the market for retail banking services, it is the major banks that dominate, and other players follow their lead.

So, standing back, the Big Four are dominant, exert structural market power to the detriment of their customers and the broader society. We are paying through the nose to bolster their profitability. Something needs to change. I will share my own thoughts in a subsequent post.