Do you think you are paying more than you should for energy, banking, insurance, internet and phone services? You are not alone, and you are probably right. From The Conversation.

Companies offer a growing number of deals that supposedly enable you to choose what is best for you. Every basic economics textbook tells us greater choice should deliver cheaper prices. But in reality this isn’t necessarily the case.

So what’s going on?

A big part of the answer is that businesses are taking advantage of the behavioural phenomenon of “consumer paralysis” to maximise profits.

They provide us with many plans and deals to make us feel like we are in control, but too many choices actually leads most of us to make a bad (or no) choice.

Energy pricing

Let’s consider how this works in the context of Australia’s electricity market.

In most areas of the country, residential customers have at least half a dozen retailers to choose from.

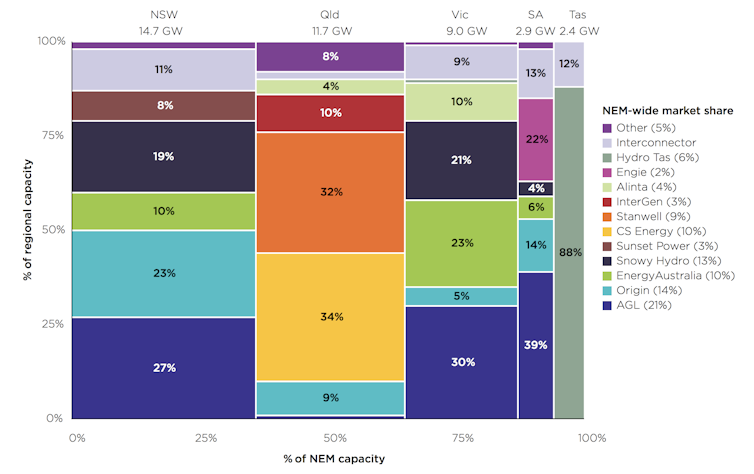

Nonetheless, according to the Australian Consumer and Competition Commission, electricity prices and profit margins are among the highest in the world, and rising. The consumer watchdog calculates that in the decade to 2018 the average residential electricity bill increased by 55% (or 35% in real terms) – and only a very small part of that had to do with alleged culprits such as renewable energy.

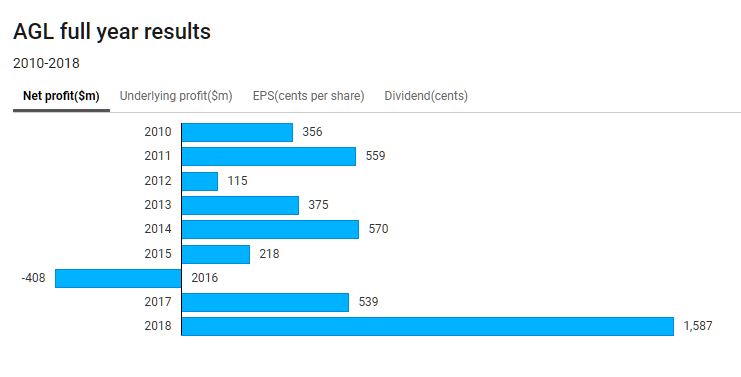

Australia’s biggest electricity company, AGL, made a net profit of A$1.6 billion in 2018 – 194% more than the year before.

Depending on where you live, AGL offers up to 11 energy plans to residential customers. There’s the “Savers” plan, “Savers Online”, “Everyday”, “Freedom”, “Standing Offer”, “Essentials”, “Essentials Plus”, and so on.

Each plan, in turn, has four to eight tariff type options: “Flexible Price”, “Time of Use Interval”, “5 Day Time of Use”, “Single Rate”, “Two rate: single rate with controlled load”, “Single Rate Demand Opt-in”, and so on.

That adds up to literally dozens of price plans from just one retailer. Other companies are hardly better. For a customer in inner Sydney, there are more than 350 retail plans to choose from.

All this “choice” gives the appearance of a competitive market, but its effect is the opposite. It give retailers wriggle room to charge more, not less.

Experiments in choice behaviour

Many experiments over the past three decades have demonstrated the ubiquity of too much choice leading to consumer paralysis.

One classic experiment was run by psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper in a San Francisco supermarket in 1999. Customers visiting the store were given a chance to sample jams. Half the time they were allowed to taste up to six jams; the other half they could taste up to 24 jams.

Traditional economics says a consumer is much more likely to find a jam they really like with a sample of 24 rather than six. So offering 24 jams should lead to more jam purchases.

Yet exactly the opposite was found. Of the consumers who chose to taste jams, only 3% of those who could sample 24 jams ended up buying jam, whereas 30% (or 10 times more) of those who could sample just six jams ended up buying.

More choices provided, more paralysis.

More recently, in 2012, Iyengar’s Columbia University colleague Eric Johnson and others reported on an experiment with much greater consequences.

They asked people to choose health insurance coverage from a set of four or eight options. The options varied on monthly premiums and deductibles. When given four options, 42% of subjects chose the best value option. On average their choices cost about $200 more than the best option on offer.

When given eight options, only 21% chose the best option – no better than simply making a random choice.

Reinforcing psychological biases

Given the massive number of products and plans available in the energy, banking, insurance, internet and mobile phone sectors, the time and effort needed to choose the best deal leaves us feeling overwhelmed and overloaded. In response, we rely on shortcuts (rules of thumb) to save both time (and our sanity).

But these shortcuts can also cause biases that result in further paralysis, including:

- Present bias – we put much greater weight on the present than the future. Since the cost of making decisions happens in the present (like the time and effort to compare options and switch services) while the benefits happen later (like saving money), we minimise the time we spend making decisions

- Status quo bias – we tend to stick with a chosen option or default, even when a much better option may be available

- Loss aversion – we place much greater weight on losses and often overestimate the chance of a bad outcome.

There is considerable evidence pointing to how these biases lead to consumer paralysis in the retail banking and energy sectors.

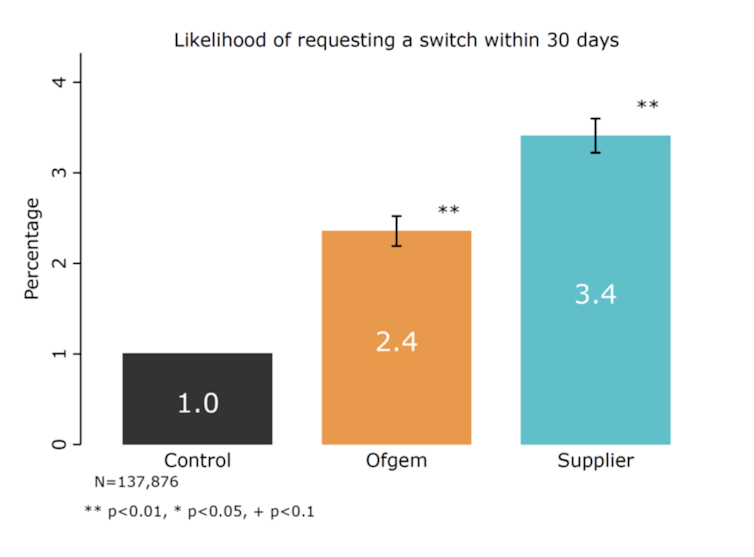

In 2017, Britain’s energy regulator, Ofgem, ran a randomised control trial involving more than 130,000 electricity customers. Participants received personalised letters either from Ofgem or their current provider offering substantially better electricity deals.

The result: compared with the control group in which only 1% switched tariffs within the next month, 3.4% of those who received an offer from their electricity provider switched to a better deal. Even when presented with notable savings, more than 96% stuck with the status quo.

Other Ofgem research shows that among those who have not switched energy plans, 51% consider it a hassle they don’t have time for, and 48% worry that things would go wrong.

Yvette Hartfree and her colleagues at the University of Bristol’s Personal Finance Research Centre have noted similar fears among bank customers: “The biggest concern for those considering switching is that something will go wrong at some point in the process of switching.”

Taking action

We should not be surprised that energy companies and others use an avalanche of choice to confuse us. It is a brilliant business strategy: it seems more competitive from a traditional assessment, yet actually reduces competition.

So what can you do?

On your own, you will need to make a conscious effort to overcome paralysis. You need to devote the time to carefully compare offers.

Fortunately, you can find tools that can help, such as the Australian government’s energy comparison website. However, be wary of commercial “switching services” and websites that provide comparisons. These operations are often being paid by retailers. Their motives are not necessarily to direct you to the best deal.

What can we do collectively?

One option is government action to ensure switching services are trustworthy. At a minimum, there should be guidelines that switching services not take payments from retailers, and only charge you when you actually save money.

Another option is to form “consumer unions”, which can bargain collectively to get members better deals. The potential of community groups to leverage bulk-buying arrangements has been demonstrated in other contexts. In Victoria’s Gippsland region, for example, local organisations have banded together to offer discounts on renewable energy technology.

There’s no reason something similar could not be done to overcome the choice problems induced by big energy retailers and the like.

Author: Robert Slonim, Professor of Economics, University of Sydney