From Moody’s

Last Wednesday, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte announced that the newly formed government will seek to separate investment banking operations from other commercial operations, similar to the recently implemented ring-fencing in the UK.

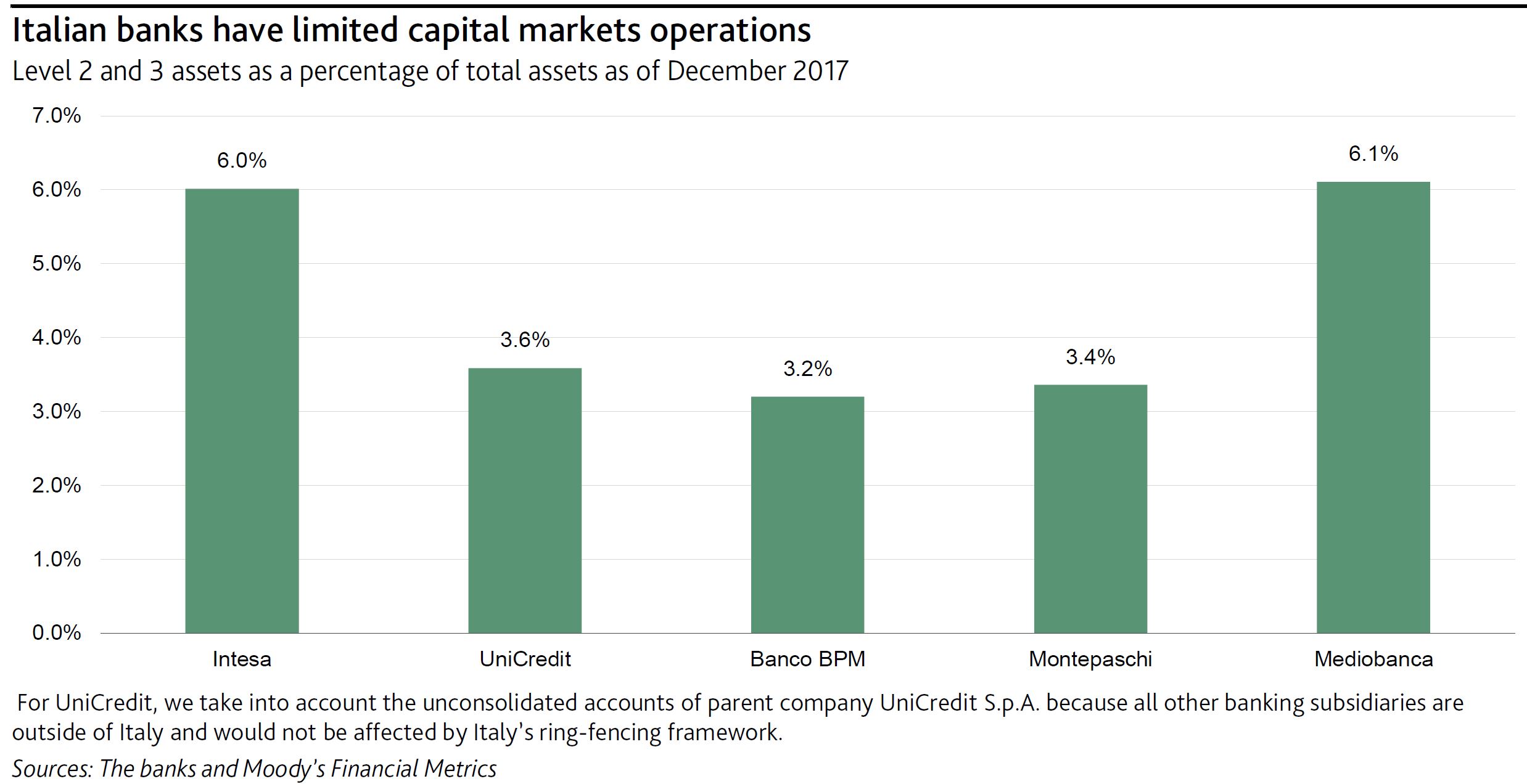

Although the government’s goal is to protect retail depositors, we believe that ring-fencing, if implemented, would have a limited effect on the operations of Italian banks because only a handful of banks have material capital markets operations that could drive losses to retail clients.

Unlike other European banks, Italian banks’ investment banking operations have not produced large losses because of their focus on more traditional commercial banking activities. Additionally, a large share of Italian banks’ investment banking activities are already booked in separate legal entities, requiring only minor structural changes.

UniCredit S.p.A. already books a large portion of its corporate and investment banking division at its wholly owned German subsidiary UniCredit Bank AG. Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. books its capital market operations at its wholly owned subsidiary Banca IMI S.p.A. Banco BPM S.p.A. and Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena S.p.A. have very limited capital market operations, and conduct most of their capital market activities through fully owned subsidiaries: Banca Akros for Banco BPM and MPS Capital Services S.p.A. for Montepaschi. Mediobanca S.p.A. already carries out its retail and investment banking activities in different legal entities.

We believe the portion of assets that would be transferred to non-ring-fenced banks would be limited for two reasons. The first is that Italy’s ring-fencing regulations will likely follow the UK model of applying only to large banks. The second is based on our calculation using the percentage of so-called Level 2 assets (whose values can be approximated using observable prices as parameters) and Level 3 assets (whose values banks estimate themselves because of a lack of observable prices) as a proxy for capital market operations, which leads us to estimate that Italy’s large banks’ Level 2 and 3 assets comprised less than 7% of their total assets as of December 2017, as shown in the exhibit.

These amounts are close to the 7% of assets that Lloyds Banking Group plc recently transferred to the newly established non-ring-fenced bank Lloyds Bank Corporate Markets plc. For Lloyds, before the implementation of ring-fencing, we had noted that the new framework was unlikely to materially affect the bank’s strong fundamentals; since Italian banks and Lloyds have similar business models focused on retail activities with little capital market operations, we believe that ring-fencing will also not materially affect Italian banks’ fundamentals.

Italy’s proposal to unwind mutual-bank reform is credit negative

In addition, Italy’s Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte announced that the newly formed government would seek to reverse the previous government’s reforms to consolidate the fragmented mutual-bank sector, without providing a specific rationale. If adopted, mutual banks would not be required to become affiliated with a group with shared cross-guarantees — an attempt to consolidate Italy’s highly fragmented banking system. The proposal, if enacted, would be credit negative for mutual banks because these small institutions will remain exposed to a fragile operating environment, with limited product diversification and economies of scale, and will not reap the benefits of being part of a large and cohesive group.

Mutual banks are savings banks in which each shareholder has one vote irrespective of the number of shares held. In December 2017, Italy had 295 mutual banks, which in aggregate comprised a material portion of the Italian banking system, accounting for a 7.8% market share for retail funding (deposits and bonds) and a 7.2% market share for loans. With the reform to consolidate mutual banks, the previous government wanted to improve financial stability in Italy by creating larger and more solid mutual banking groups. Doing so would have created banks with sufficient scale to access the international equity and debt markets and face challenges from the operating environment, reducing the risk of weaker banks failing.

On a standalone basis, single mutual banks are generally small, averaging 14 branches, 100 employees and around €400 million in loans and retail funding. If they were combined into a single group, mutual banks would be the third-largest banking group in Italy, with €131 billion loans after UniCredit S.p.A. and Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. And, although some have performed well, several have been put under administration by the Bank of Italy or required rescue by other mutual banks.

Currently, mutual banks have a certain degree of independence and can decide at their discretion the level of integration within Italy’s mutual bank network. This structure leaves them exposed to daunting challenges including competition, low profitability from traditional mortgage and savings business in the low interest rate environment, large investments in digitalisation to meet changing customer behaviour and