When we released our mortgage stress report for June 2018, we said that the number of households exposed to risks is rising, and if rates were to increase then around 1 million of households will fall into stress and some may default, up from 970,000 now.

The RBA minutes yesterday focussed in on the problem of household debt.

Members held a detailed discussion of the high level of household debt in Australia, informed by a special paper prepared for this meeting. Household debt has increased by more than household income over the preceding three decades in many countries, but particularly so in Australia. Two key drivers of this trend across countries have been the decline in nominal interest rates, predominantly reflecting lower inflation, and financial deregulation, both of which have increased households’ access to finance. Members noted that a distinguishing feature of the Australian housing market is that the bulk of dwellings are owned by the household sector. This has contributed to greater borrowing for housing by households in Australia compared with other countries, where the corporate sector owns a larger proportion of rental properties. Another feature of the Australian housing market that has contributed to greater borrowing by households is the higher cost of housing in Australia on account of a larger share of the Australian population living in urban centres, typically in large detached dwellings.

Survey data indicate that much of Australian household debt is owed by higher-income and middle-aged people, who tend to have more stable employment and often larger savings buffers. However, members recognised that a material share of household debt is held by lower-income households, which generally have higher debt relative to their income. Household assets in aggregate are valued at around five times the value of household debt and total assets exceed the value of debt for most households. Members noted, however, that most household assets are housing and superannuation, and that both of these are illiquid.

Members noted that high levels of household debt could affect economic outcomes. For example, households with high debt levels are more vulnerable to economic shocks and therefore more likely to reduce consumption in the face of uncertainty about their future income. Members also noted that changes in interest rates have a larger effect on disposable income for households with high debt levels, but that these households may be less inclined to borrow more at times when interest rates fall. Accordingly, members agreed that household balance sheets continued to warrant close and careful monitoring.

In fact our research says, yes, debt is a problem, and it is hitting many different types of household, including more affluent ones.

Our analysis of stress and defaults created a stir in the media, several radio and TV interviews, and some interesting discussions on social media.

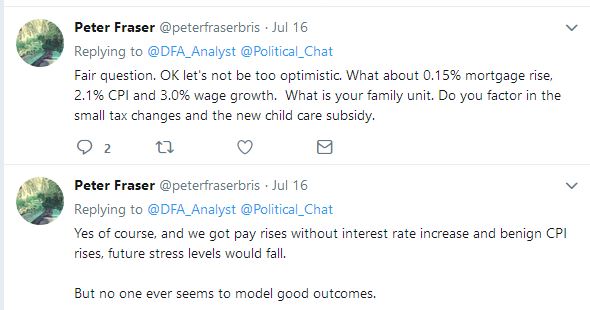

One of these, with Peter on Twitter led to a question about how we make our assessment and scenarios and our definitions of mortgage stress (cash-flow based). We include estimates of expected wages growth, inflation, cpi, interest rates etc.

So this led to a discussion where I volunteered to run a scenario using Peter’s parameters.

We also added in the tax changes and child care subsidy (in both scenarios). We do not impose a particular family structure, but capture that in our surveys (which aligns to the ABS census distribution).

We also added in the tax changes and child care subsidy (in both scenarios). We do not impose a particular family structure, but capture that in our surveys (which aligns to the ABS census distribution).

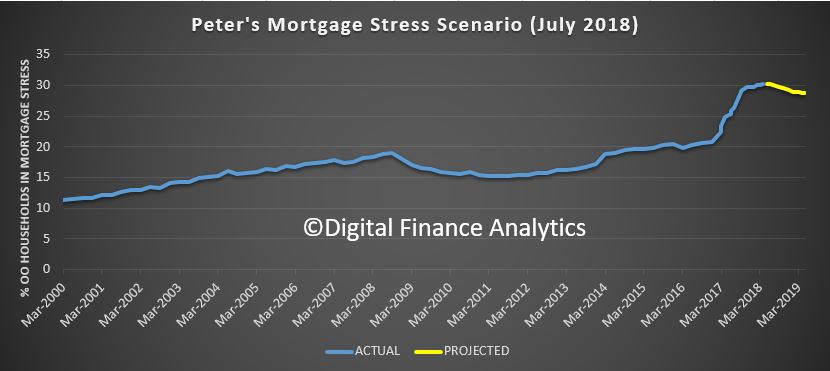

So, we ran our model with a 3% wage growth, 2.1% CPI and small rise in mortgage rates. Stress levels would begin to fall, but will still be higher than since 2000, because of the greater leverage and debt burden.

Here are the results, one year down the track.

Here are the results, one year down the track.

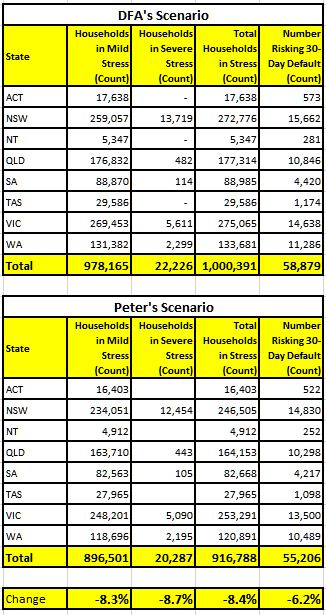

So the impact of potential wages rises, in real terms is significant. A “good outcome!” However even then the risk in the system remains higher than we have been use to. Defaults reduced by 6% while stress fell by more than 8%.

So the impact of potential wages rises, in real terms is significant. A “good outcome!” However even then the risk in the system remains higher than we have been use to. Defaults reduced by 6% while stress fell by more than 8%.