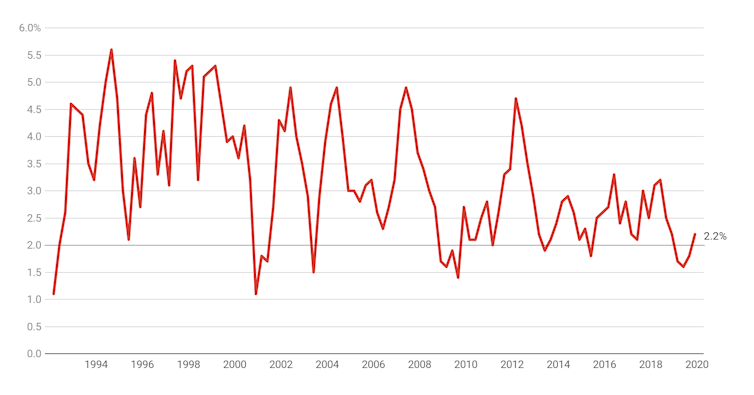

The good news is our economy was performing better than had been thought in the lead-up to the bushfires and coronavirus. Via The Conversation.

Updated figures in Wednesday’s national accounts show the economy grew 0.6% in the three months to September, rather than the 0.4% previously reported, and a healthier-than-expected 0.5% in the three months to December.

Combined, these figures pushed annual economic growth up above 2% to 2.2% for the first time in a year in which it had been below 2% for the longest period since the global financial crisis.

Annual GDP growth

Not to put too fine a point on it, it looks as if we were actually experiencing the the “gentle turning point” repeatedly promised by Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe.

As Lowe put it during the second half of last year:

After having been through a soft patch, a gentle turning point has been reached. While we are not expecting a return to strong economic growth in the near term, we are expecting growth to pick up.

The figures show the economy began (gently) picking up after the Reserve Bank began cutting rates in June. Counting this week’s latest interest rate cut, it has cut four times.

But the coronavirus and the bushfires have consigned the turning point to history.

Negative growth now possible

Not for a minute does Treasurer Josh Frydenberg believe the economy continued to improve this quarter, the March quarter.

Reminded that the support package promised by the prime minister will come too late for the three months to March, and reminded that many businesses haren’t been able to trade much, Frydenberg was asked to assess the risk the economy might now be going backwards, a state of affairs that if it continued long enough would be a recession.

He replied that the Treasury believes the bushfires alone will shave 0.2 points from growth in the March quarter. Added to that will be the risk from the spread of the coronavirus, which he believes will be “substantial”.

Tonight (Wednesday) Frydenberg and Treasury officials will take part in a phone hookup with other members of the International Monetary Fund to discuss developments including interest rate cuts in both Australia and the United States.

Treasury update on Thursday

The Treasury will finalise its estimate of the impact of the coronavirus on March-quarter GDP later in the evening and report it to a Senate estimates hearing beginning at 9am Thursday.

It means we will know the likely impact at about the same time as the treasurer.

To support retirees hurt by four near-consecutive rate cuts, the treasurer is considering cutting the deeming rate – the rate investments are deemed to have earned for the purposes of the pension income test. It’ll be the second deeming rate cut in the space of a year and will make it easier for retirees earning very little to remain on the pension.

The focus of the support package will business investment, which slid an unexpected 1.1% in the final three months of the year and 3.4% over the course of the year in defiance of budget forecasts it would climb.

Standard of living slipping

Although not ruling out support for householders, Frydenberg said mortgage holders had done well out of the past four rate cuts. Households with A$400,000 mortgages could soon be paying $3,000 less per year than they had in June.

Living standards, as measured by the Reserve Bank’s preferred measure, real net national disposable income per capita, went backwards in the December quarter, slipping 1.3%. Over the year, it climbed just 1.2%.

Household spending recovered somewhat, climbing 0.4% in real terms in the December quarter after inching ahead only 0.1% in the September quarter.

Throughout the year to December, real household spending grew 1.2% at a time when Australia’s population grew 1.5%. This means the consumption of goods and services per person went backwards.

Government spending provided substantial support. Over the year to December public spending on infrastructure grew 4.1% in real terms.

Deputy Prime Minister Michael McCormack said on Wednesday he would try and boost that by asking state and local governments to bring forward whatever projects they could, to start work in the next three to six months.

Recurrent government spending grew 5%.

Author: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University