Steve Mickenbecker from Canstar and I discuss the complexity of health insurance

https://www.canstar.com.au/team-members/steve-mickenbecker/

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

Steve Mickenbecker from Canstar and I discuss the complexity of health insurance

https://www.canstar.com.au/team-members/steve-mickenbecker/

We discuss the recent ACCC report on the Private Health sector, where the number of households covered is decreasing, premiums are rising faster than wages or inflation, more policies have exclusions and more households are being hit with a “gap” payment.

Plus there are concerns about data privacy especially relating to third party health and fitness apps. There is a lot which needs attention. Perhaps the industry should see a Doctor!

The ACCC just released their 21st report into the Private Health Insurance Sector, which analyses key competition and consumer developments and trends in the private health insurance industry to 30th June 2019 that may have affected consumers’ health cover and out-of-pocket expenses. This report also continues the ACCC’s focus on adequate private health insurer

communications to their consumers, including on detrimental policy changes, as well as potential emerging issues in the use of consumer data.

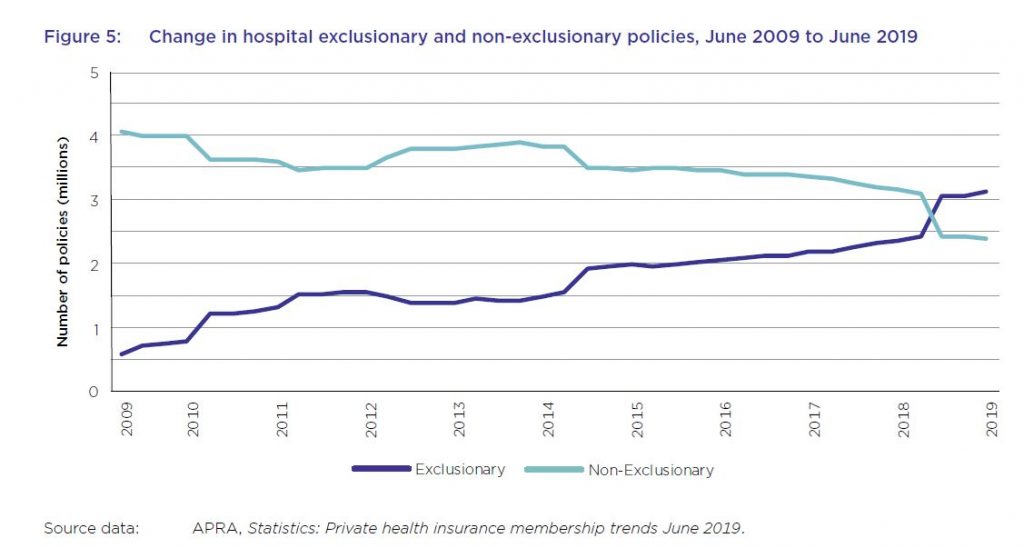

And in summary the system is unwell. Private health insurance premiums rise faster than income despite growing exclusions. For the first time, the majority of hospital treatment policies held by Australians now contain exclusions with more than 57 per cent of policies containing exclusions, up from about 44 per cent in the previous year. This chimes with our household surveys which shows more younger people are jettisoning their policies, or not signing up in the first place. This is a wicked problem, as more sick people as a total proportion are within the system, meaning that costs are becoming more concentrated.

Plus, the ACCC notes that consumer data collected by private health insurers and other businesses, for example through wellbeing apps and rewards schemes, can be used for a number of purposes such as targeted marketing, including from third parties.

Key industry data used and relied upon by the ACCC includes industry statistics and data collected by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) and private health insurance complaints data from the Private Health Insurance Ombudsman (PHIO).

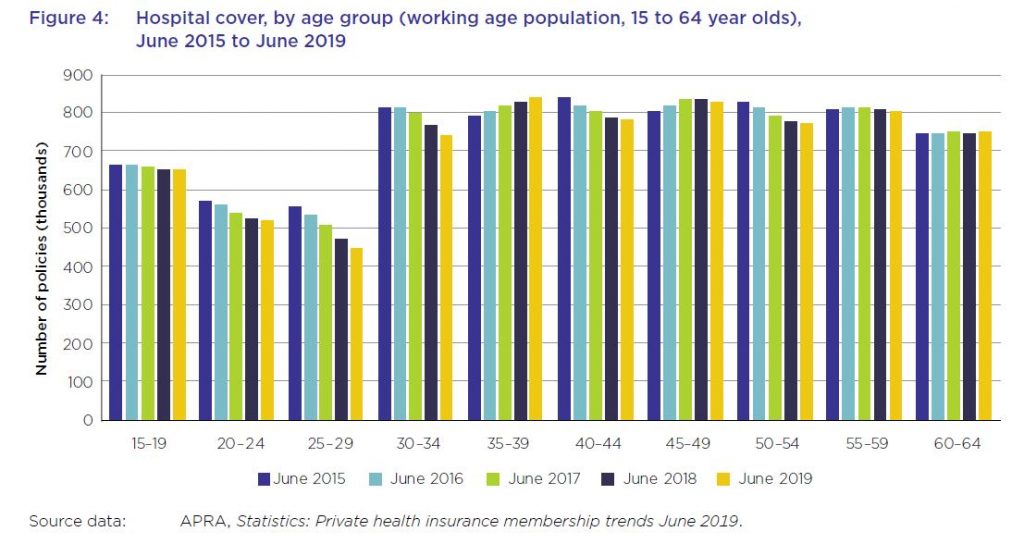

As at 30 June 2019, 13.6 million Australians, or 53.6 per cent of the population, had some form of private health insurance. This represents a membership reduction of 0.6 per cent from June 2018 (54.2 per cent). The Australian population grew by 396 722, or almost 1.6 per cent, during this period. The decline is sharpest among younger age groups.

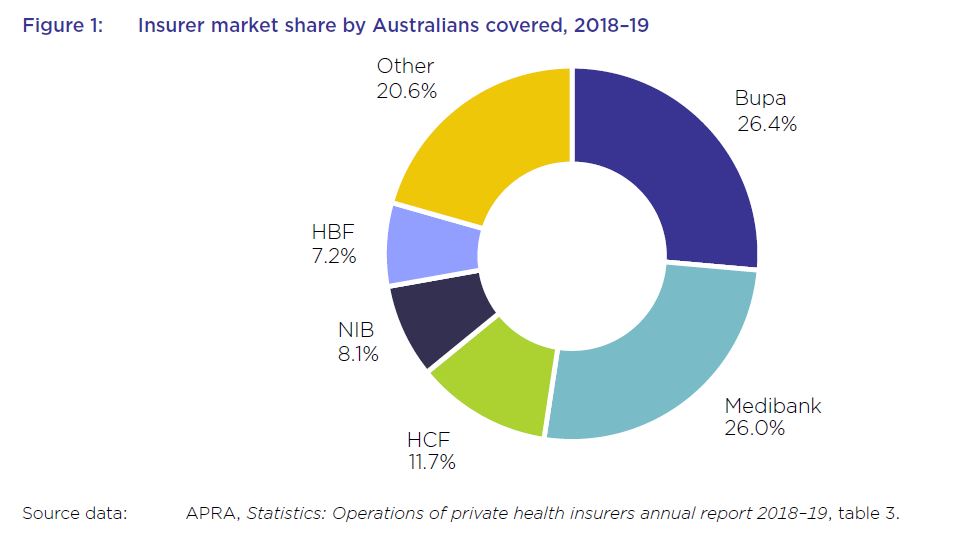

The five largest health insurers have a combined market share of almost 79.5 per cent and contributed to almost 77.5 per cent of total health fund benefits paid in 2018–1915, with Bupa and Medibank contributing 26.7 per cent and 25 per cent respectively.

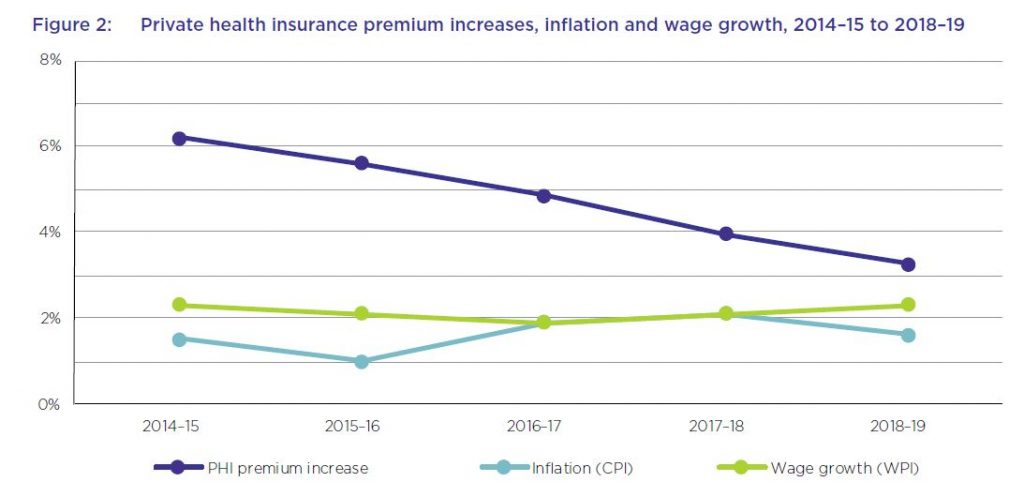

The average premium increase of 4.8 per cent per year over this period has been higher than the average annual growth in the wage price index (2.1 per cent) and the consumer price index (1.6 per cent) over the same period. While the rate of the average yearly premium increases has been decreasing each year over the past five years, and was 3.25 per cent in 2018–19, the average industry premium change for 2020, to take effect on 1 April 2020, will be 2.92 per cent – still well above wages growth.

From June 2018 to June 2019, the proportion of hospital policies held with exclusions increased by almost 14 per cent. For the first time, the majority of policies held now have exclusions.

The number of exclusionary policies held increased by over 650 000 from June 2018 to September 2018, with an equivalent reduction in non-exclusionary policies during the same period. APRA’s statistics did not indicate the reasons for this rise in the number of exclusionary policies during the reporting period. However, analysis by Silvester and others has suggested that less expensive exclusionary policies may appeal both to existing policyholders whose policies have become unaffordable, as well as to young people buying health insurance to avoid LHC loading and the

Medicare levy surcharge.

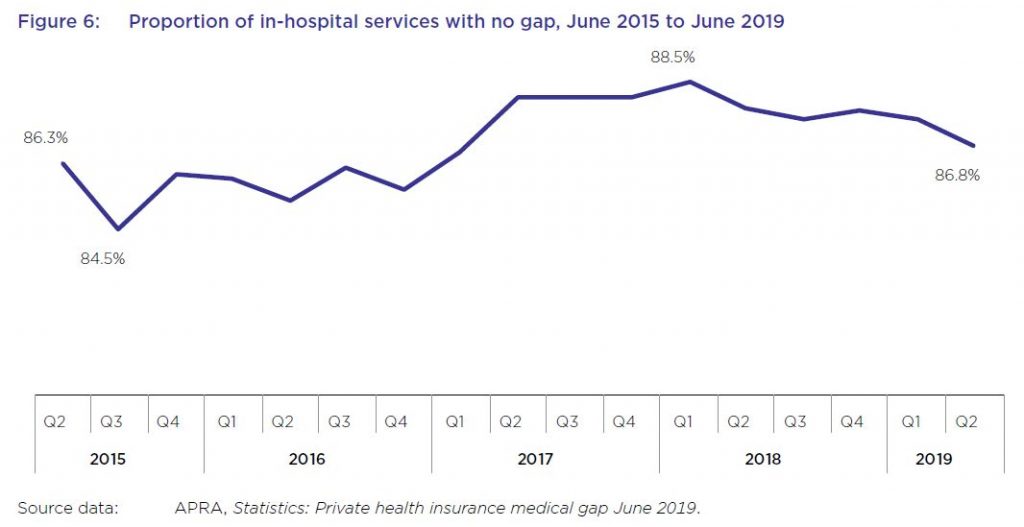

While most in-hospital services are delivered with no gap payments required from patients, this rate has varied in recent years, from a low of less than 85 per cent of services not requiring a gap payment in September 2015, to almost 89 per cent in March 2018, before falling again to under 87 per cent in June 2019.

From June 2018 to June 2019, the average gap expense incurred by a consumer for hospital treatment was $314.51, an increase of 1.9 per cent from the previous year, as shown in table 8. Average gap payments for extras treatment increased by almost 4 per cent to $49.20 over the same period.

A YouGov survey from late 2019 found that, after the cost of premiums and a perceived lack of value for money, out-of-pocket costs were a leading reason given by respondents for no longer holding private health insurance.

Several health insurers offer rewards schemes for their members, some of which involve the use of fitness tracking apps and devices to record activities such as steps and sleep. Some of these apps operate in conjunction with companies other than health insurers. For example, the health insurers MO Health and GMHBA are both partnered with the life insurer AIA Australia Limited, and use the AIA Vitality program issued by AIA.

HCF has also entered into a partnership with Flybuys where new HCF members can collect Flybuys points based on their annual health cover

premiums. Qantas, which offers health insurance issued by NIB, also offers frequent flyer points for members who download the Qantas Wellbeing app and undertake certain activities. Its Qantas Wellbeing Program Terms and Conditions state that members must link a tracking device to record their physical activity, and that as members, they consent to Qantas: “collecting, using and disclosing any personal information including health and Wellbeing information submitted by the Member through joining or use of the Wellbeing Program or collected by Qantas through the Tracking Device or the Qantas Wellbeing App”.

Although Australians can receive benefits from rewards and discounts offered by health insurers and other organisations that collect consumer data, the ACCC is concerned that few consumers are fully informed of, fully understand, or can effectively control, the scope of data collected when they sign up for, or use, such services.

While the community rating system for private health insurance in Australia prohibits insurers from charging different private health insurance premiums to individual consumers based on health and other

factors, the ACCC notes that the consumer data collected by wellbeing apps and rewards schemes could be used for a number of other purposes, including for targeted marketing (including from third parties), and potentially to create insights that could be shared with or sold to third parties.

The system will continue to be under pressure – and we think the model is frankly broken.

The ACCC has released its 16th report to the Australian Senate on competition and consumer issues in the private health insurance industry for the period 1 July 2013 to 30 June 2014. The ACCC has previously found that the industry is characterised by information asymmetry and complexity. These findings have been replicated in this report. The ACCC has an obligation to provide an annual report on competition and consumer issues within the private health insurance industry under an Australian Senate order. However, seems that not much follows from such reviews!

The private health insurance industry is an important component of the Australian health care system. The number of people with private health insurance has been growing steadily, with year on year average increases of 2.5 per cent over the last 10 years. At the end of 2013–14, 47.2 per cent of the population was covered for hospital treatment and 55.2 per cent was covered by general treatment policies, commonly referred to as ‘extras’ cover. Health insurers generate revenue from the sale of health insurance policies as well as through the investment of premium reserves. Currently there are over 20 000 private health insurance policies on offer to consumers in Australia. Over the next five years, industry revenue and profit are forecast to grow at a compound annual rate of 6.4 per cent to reach $28.8 billion. Annual revenue in 2014-15 is estimated at $21.1bn and returning $1.5bn in profit. There are 34 businesses providing health care insurance.

Their main findings were:

First, there are market failures due to asymmetric and imperfect information. This leads to complexity in private health insurance policies, which reduce consumers’ ability to compare policies and make informed choices. Further, consumers have limited information about their likely future health needs, which may lead to consumers underestimating their future medical needs and instead focusing on the immediate costs and benefits of private health insurance.

Second, existing regulatory settings can change consumers’ incentives in purchasing private health insurance and drive insurers to offer products to primarily reduce consumers’ tax liabilities, rather than also focussing on consumers’ current and future medical needs (which are difficult to predict). As funds respond to market demand for affordable policies, there are increasing policy limitations and exclusions leading to higher numbers of consumers having policies with less cover than they expected. This leads to an increased risk of consumers facing unexpected out-of-pocket expenses and general dissatisfaction with the system. We accept that some consumers in purchasing private health insurance may only be seeking to reduce their tax burden and/or the risk of the LHC loading. However, they still expect basic

cover from their purchase.

Third, while health insurers may be strictly compliant with the requirements of the Private Health Insurance Act and the Code, the research has revealed examples where representations by insurers to consumers, including when entwined with policy variations, may be at risk of breaching the consumer laws.

There were some interesting consumer insights:

Consumers’ understanding of policy benefits and exclusions will vary depending on the complexity of the information provided and their familiarity with the health system and their health needs. Where insurers provide information that is overwhelming, incomplete or complex, it is less likely that consumers will be able to exercise informed choices to purchase cover that is appropriate to their needs and circumstances. In turn, these consumers are more likely to face unknown or hidden costs of private services that are not covered in full by their insurance. There are a range of factors in the private health sector that increase complexity for consumers, including:

Adding to the complexity is the sheer number of options available, and that each insurer has different terminology and ways of presenting information, which makes comparisons difficult. Policies can contain a mix of levies, surcharges and rebates. Sometimes the specific details are hidden or obscured in lengthy and complex policy documents that are not easily accessible to consumers. In addition, private health insurance contracts allow for the insurer to unilaterally vary a consumer’s policy terms, conditions and exclusions (subject to private health insurance legislation). This means that even where a consumer spends considerable effort in understanding the policies on offer in order to make an informed choice, that effort may become redundant if an insurer subsequently decreases the cover provided. Under the ACL, provisions that allow such unilateral variations may constitute unfair contract terms (subject to a number of exemptions), particularly if the term is not transparent and causes consumer detriment.

The mix of levies, combined with a tendency by funds to change their policies over time, make it difficult for even astute consumers to judge the true cost and value of their private health insurance.

Most consumers with private health insurance will access some of their benefits at some point. The quantitative research found that while 30 per cent of consumers rarely access their benefits, 43 per cent sometimes do and 18 per cent do so frequently. Eight per cent had not yet accessed their private health insurance. The quantitative research also indicates that consumers who regularly use their private health insurance are more likely to feel informed about their health insurance, and confident they have received all they expected in terms of their rebate or claim. However, the data further discloses

that one quarter of consumers who have accessed their benefits have experienced at least one occasion where their expectations were not met, largely because they were dissatisfied with the claim amount or believed they were covered for something that they were not.

The quantitative research found that just under two thirds of all respondents have had private health insurance for 10 or more years. However, only 14 per cent of respondents had changed insurers, despite 48 per cent having thought about changing insurer and some taking steps to do so without completing the transaction. For respondents who have changed insurer or contemplated it, the most reported reason was that the premium was too expensive (57 per cent), followed by dissatisfaction with claim amount and policy benefits and exclusions (both 6 per cent). Respondents who have thought about changing private health insurers but have not done so, reported that their main reason for not changing was that they have not found an insurer that meets their needs (21 per cent), whilst 12 per cent considered that the process of changing is too difficult.