The latest update of finance and property news to 19 March 2020 What has the RBA been up to?

RBA Pulls Out All The Stops

My latest radio interview on ABC Illawarra

Small Lenders To Be Supported

The Treasurer has announced a second stimulus plan as Australia fights to contain the economic impact of the coronavirus.

Hours after the emergency rate cut by the Reserve Bank, the Prime Minister and Treasurer addressed Australia announcing a further $15 billion investment to enable smaller lenders to continue supporting Australian consumers and small businesses.

This funding will complement the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA’s) announcement of a $90 billion term funding facility for authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) that is also expected to support lending to small and medium enterprises.

The government’s latest action is aimed to enable customers of smaller lenders to continue to access affordable credit as the world deals with the significant challenges presented by the spread of coronavirus.

“Small lenders are critical to Australia’s lending markets, often driving innovation and providing competition for larger lenders,” said the Treasurer Josh Frydenberg.

“Combined, these measures will support the continued ability of lenders to support their customers and in doing so the Australian economy,” the Treasurer added.

The Treasurer confirmed that the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) will be provided with an investment capacity of $15 billion to invest in wholesale funding markets used by small ADIs and non-ADI lenders.

The $15 billion capacity would allow the AOFM to support a substantial volume of expected issuance by these lenders over a 12 month period.

“Importantly the assets being purchased by the AOFM will not be limited to residential mortgage backed securities.

“The AOFM will also be able to invest in a range of other asset backed securities and warehouse facilities. The Government will provide the AOFM with investment guidelines that will outline the basis on which the AOFM is to undertake these investments,” the Treasurer added.

Enabling legislation will be introduced in the week commencing Monday, 23 March 2020. The AOFM is expected to be able to begin investing by April.

Australia Shuts Borders

All non-citizen, non-resident travellers will be banned from entering Australia, as the government attempts to get a handle on the coronavirus outbreak.

“We believe it is essential to take a further step to ensure we are now no longer allowing anyone, unless they are a citizen or resident or direct family member,” Scott Morrison said in an address on Thursday afternoon.

The government’s reasoning is that a significant majority of cases are not contracting the virus through community transmission, but by contact with someone who has recently travelled from overseas.

“The reason for this decision is about 80 per cent of the cases we have in Australia are either the result of someone who has contracted the virus overseas or someone who has had a direct contact with someone who has returned from overseas,” he said.

Earlier this week, the government announced all Australians currently overseas should return home immediately, using commercial flights

APRA Drops Capital Requirements

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) today announced temporary changes to its expectations regarding bank capital ratios, to ensure banks are well positioned to continue to provide credit to the economy in the current challenging environment.

Over the past decade, the Australian banking system has built up substantial capital buffers. The highest quality form of capital, Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital, reached $235 billion at the end of 2019. As a result, banks are typically maintaining capital levels well above minimum regulatory requirements.

In 2017, APRA set benchmark capital targets for banks to enable them to be regarded internationally as unquestionably strong (which was a recommendation of the 2014 Financial System Inquiry). These benchmarks are well above current minimum regulatory requirements. For the four major banks, for example, this benchmark equated to having a CET1 ratio of at least 10.5 per cent of risk-weighted assets. A lower benchmark applies for smaller banks. In comparison, the actual CET1 ratio of the banking system by the end of 2019 had reached 11.3 per cent.

APRA is advising all banks today that, given the prevailing circumstances, it envisages they may need to utilise some of their current large buffers to facilitate ongoing lending to the economy. This is especially the case for banks wishing to take advantage of new facilities announced today by the Reserve Bank of Australia to promote the continued flow of credit. Provided banks are able to demonstrate they can continue to meet their various minimum capital requirements, APRA would not be concerned if they were not meeting the additional benchmarks announced in 2016 during the period of disruption caused by COVID-19.

APRA Chair Wayne Byres said: “APRA has been pursuing a program to build up the financial strength of the system for many years, when banks had the capacity to do so. As a result, the Australian banking system is well-capitalised by both historical and international standards.

“APRA’s objective in building up this capital strength has been to ensure it is available to be drawn upon if needed in times such as this. Today’s announcement reflects the underlying strength of the system: even if the banking system utilises some of its current large buffers, it will still be operating comfortably above minimum regulatory requirements,” Mr Byres said.

RBA Cuts And More

RBA said: The coronavirus is first and foremost a public health issue, but it is also having a very major impact on the economy and the financial system. As the virus has spread, countries have restricted the movement of people across borders and have implemented social distancing measures, including restricting movements within countries and within cities. The result has been major disruptions to economic activity across the world. This is likely to remain the case for some time yet as efforts continue to contain the virus.

Financial market volatility has been very high. Equity prices have experienced large declines. Government bond yields have declined to historic lows. However, the functioning of major government bond markets has been impaired, which has disrupted other markets given their important role as a financial benchmark. Funding markets are open to only the highest quality borrowers.

The primary response to the virus is to manage the health of the population, but other arms of policy, including monetary and fiscal policy, play an important role in reducing the economic and financial disruption resulting from the virus.

At some point, the virus will be contained and the Australian economy will recover. In the interim, a priority for the Reserve Bank is to support jobs, incomes and businesses, so that when the health crisis recedes, the country is well placed to recover strongly.

At a meeting yesterday, the Reserve Bank Board agreed to the following comprehensive package to support the Australian economy through this challenging period:

- A reduction in the cash rate target to 0.25 per cent. The Board will not increase the cash rate target until progress is being made towards full employment and it is confident that inflation will be sustainably within the 2–3 per cent target band.

- A target for the yield on 3-year Australian Government bonds of around 0.25 per cent. This will be achieved through purchases of Government bonds in the secondary market. Purchases of Government bonds and semi-government securities across the yield curve will be conducted to help achieve this target as well as to address market dislocations. These purchases will commence tomorrow. The Bank will work closely with the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) and state government borrowing authorities to ensure the efficacy of its actions. Further details about the implementation of this are provided in the accompanying notice.

- A term funding facility for the banking system, with particular support for credit to small and medium-sized businesses. The Reserve Bank will provide a three-year funding facility to authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) at a fixed rate of 0.25 per cent. ADIs will be able to obtain initial funding of up to 3 per cent of their existing outstanding credit. They will have access to additional funding if they increase lending to business, especially to small and medium-sized businesses. This facility is for at least $90 billion. Further details are available in the accompanying notice. The Australian Government has also developed a complementary program of support for the non-bank financial sector, small lenders and the securitisation market, which will be implemented by the AOFM.

- Exchange settlement balances at the Reserve Bank will be remunerated at 10 basis points, rather than zero as would have been the case under the previous arrangements. This will mitigate the cost to the banking system associated with the large increase in banks’ settlement balances at the Reserve Bank that will occur following these policy actions.

The Reserve Bank will also continue to provide liquidity to Australian financial markets by conducting one-month and three-month repo operations in its daily market operations until further notice. In addition, the Bank will conduct longer-term repo operations of six-month maturity or longer at least weekly, as long as market conditions warrant.

The various elements of this package reinforce one another and will help to lower funding costs across the economy and support the provision of credit, especially to small and medium-sized businesses.

Australia’s financial system is resilient and well placed to deal with the effects of the coronavirus. The banking system is well capitalised and is in a strong liquidity position. Substantial financial buffers are available to be drawn down if required to support the economy. The Reserve Bank is working closely with the other financial regulators and the Australian Government to help ensure that Australia’s financial markets continue to operate effectively and that credit is available to households and businesses.

Today’s policy package from the Reserve Bank complements the welcome fiscal response from governments in Australia. Together, these measures will support jobs, incomes and businesses through this difficult period and they will also assist the Australian economy in the recovery.

RBNZ Says Cash and other payments systems ready for COVID-19

The Reserve Bank and the banking system have plenty of cash on hand to meet demand under any circumstances,” says Assistant Governor Christian Hawkesby. Mr Hawkesby made the statement today after public interest and discussion about cash availability and use.

“We work closely with New Zealand’s banks, the companies that transport cash, and those that supply cash-handling equipment. They are all prepared for operating during all circumstances, including any unusual challenges that COVID-19 may pose.” he says.

“As an example, the Reserve Bank has at least two years’ worth of replacement cash available to feed into the system if required. We can keep cash flowing to and from branches and ATMs in the event of staff shortages or other difficulties anywhere in the cash system.”

“The banks and electronic payments systems are prepared, resilient, and will keep operating. When people are shopping, there will be cash and other payments systems available to support that,” he says.

The Reserve Bank is also reminding shoppers and retailers to practice good hand hygiene.

“Cash is just one of a number of frequently touched surfaces we encounter. The same is true for any other payment device whether it’s a card, phone or watch. This reinforces the need for good hand hygiene regardless of the way you pay or accept payment.”

“Retailers should use common-sense when it comes to cash. Businesses are not obliged to accept cash, but declining it may end up disadvantaging people who rely on its use. These people are more likely to be young, elderly, poor, disabled or financially excluded. Have respect and care for each other,” says Mr Hawkesby.

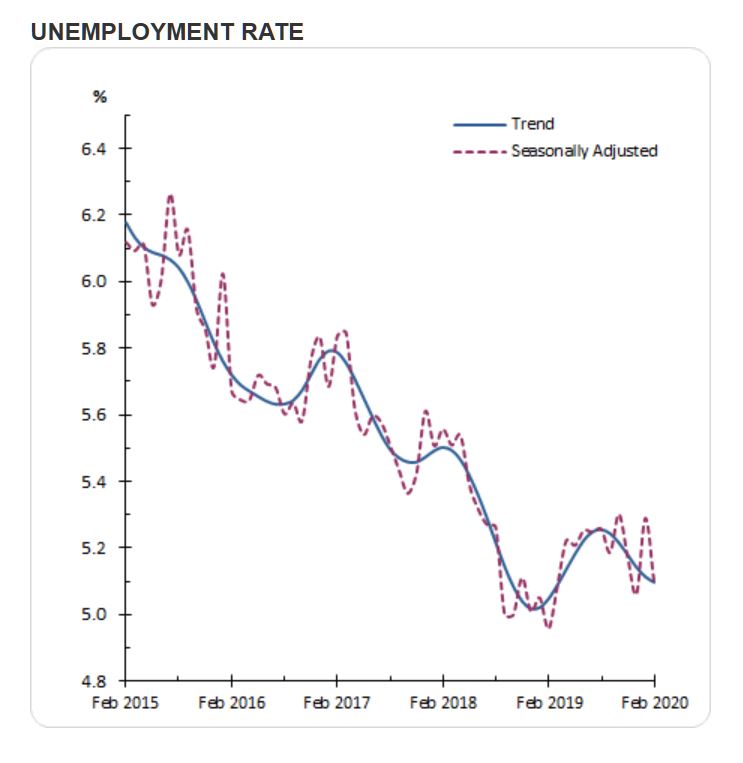

An Irrelevant Employment Number

Australia’s trend unemployment rate remained steady at 5.1 per cent in February 2020, from a revised January 2020 figure, according to the latest information released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) today.

ABS Chief Economist Bruce Hockman said: “The trend unemployment rate remained steady at 5.1 per cent for a third consecutive month.”

There was no notable impact on February 2020 Labour Force statistics resulting from the recent bushfires or COVID-19. The February reference period was in the first half of the month and pre-dates the notable increases in confirmed cases in Australia of COVID-19.

Employment and hours

In February 2020, trend monthly employment increased by around 21,000 people. Full-time employment increased by around 13,000 and part-time employment increased by around 8,000 people.

Over the past year, trend employment increased by around 241,000 people (1.9 per cent), below the average annual growth over the past 20 years (2.0 per cent).

Full-time employment growth (1.5 per cent) was below the average annual growth over the past 20 years (1.6 per cent) and part-time employment growth (2.7 per cent) was also below the average annual growth over the past 20 years (3.0 per cent).

The trend monthly hours worked decreased by less than 0.1 per cent in February 2020 and increased by 0.8 per cent over the past year. This was lower than the 20 year average annual growth of 1.6 per cent.

“We have seen a decrease in the trend hours worked in recent months, even though employment has continued to grow. This largely reflects a fall in the total hours worked by men”, added Mr Hockman.

Underemployment and underutilisation

The trend monthly underemployment rate remained steady at 8.6 per cent in February 2020, and increased by 0.3 percentage points over the past year.

The trend monthly underutilisation rate also remained steady at 13.7 per cent in February 2020, an increase of 0.4 percentage points over the past year.

States and territories trend unemployment rate

The monthly trend unemployment rate increased in Victoria and decreased in Queensland, South Australia and Tasmania in February 2020. The unemployment rate remained steady in all other states and territories.

Over the year, unemployment rates fell in Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory. Unemployment rates increased in New South Wales, Victoria, and the Northern Territory.

Seasonally adjusted data

The seasonally adjusted unemployment rate decreased by 0.2 percentage points to 5.1 per cent in February 2020, while the underemployment rate remained steady at 8.6 per cent. The seasonally adjusted participation rate decreased by 0.1 percentage points to 66.0 per cent, and the number of people employed increased by around 27,000.

In original terms, the incoming rotation group in February 2020 had a higher employment to population ratio than the group it replaced (62.7% in February 2020, compared to 61.8% in January 2020), however it was lower than the sample as a whole (62.8%). The incoming rotation group had a higher full-time employment to population ratio than the group it replaced (43.6% in February 2020, compared to 43.4% in January 2020), and was higher than the sample as a whole (43.2%).

The incoming rotation group had a higher unemployment rate than the group it replaced (5.9% in February 2020, compared to 5.3% in January 2020), and was higher than the sample as a whole (5.5%). The incoming rotation group had a higher participation rate than the group it replaced (66.6% in February 2020, compared to 65.2% in January 2020), and was higher than the sample as a whole (66.5%).

Why Will Property Values Fall?

Despite the property bulls (who seem to be a bit quiet just now) there are a series of logical reasons why prices will indeed fall from current levels.

First net migration into Australia will stop period. We have been seeing around 300,000 each year, which was one factor supporting demand in some areas.

Second, new property transactions will stall. No one will want to attend an open house, yet alone an auction in the current conditions. Sales transactions have risen more recently, but that just got turned off. How soon will it be before we see zero auctions reported on a Saturday?

Third, property investors, will continue to flee – they already saw rental returns dropping, now no capital growth. Demand from new investors was weak, it will die. They may have to subsidise renters who cannot pay rent due to job loss or income decline.

Fourth, existing mortgage holders will face cash flow issues as income stalls. We already have more than 1 million households in cash flow stress, another 200,000 or so are set to join them, in short order. Around one quarter of households have less than one months free cash available if incomes stall.

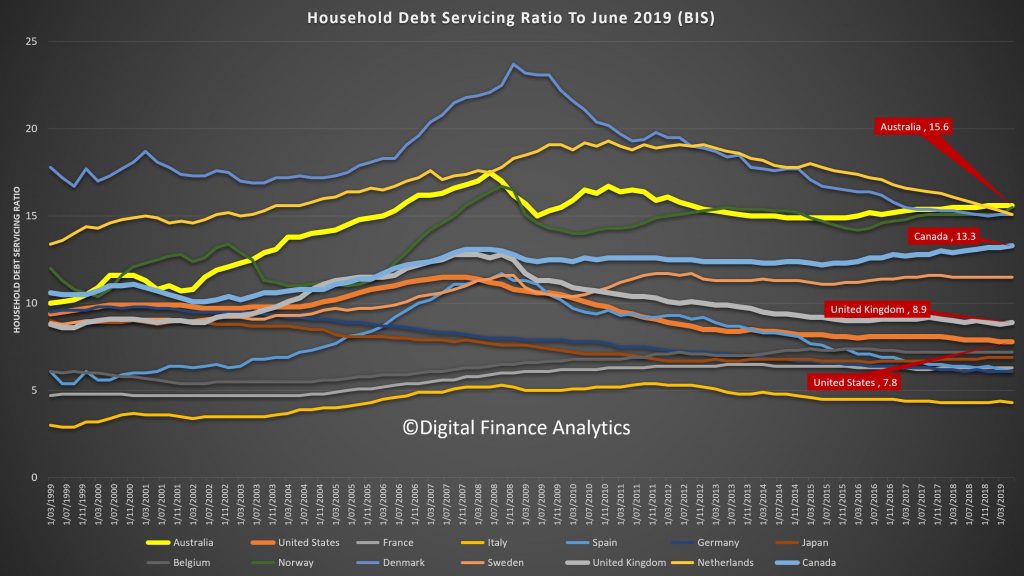

Fifth, banks will (are) cut back on mortgage lending. With margins already low, experience from Europe suggests it is unprofitable to lend. They will also lift risk underwriting standards. Meaning people if they want to borrow will get a lower available loan. Loan books will likely contain more defaults and higher risks – meaning more capital. Some may choose to shrink their balance sheets as liquidity stalls. Recently first time buyers were getting $420,000 mortgages no problems, with income ratios of 6, 7, 8 times or more. Debt servicing ratios are still high – and servicing is now an issue.

Income multiples often assumes double incomes. If one income stopped that would be a big problem.

Sixth, forced sales will eventually occur though nor immediately. I expect banks to support households in financial stress by loan and interest payment postponements, for a time. But eventually forced sales, at lower than current market values will follow. In addition, given the death rates among older people, more supply could well come on stream as estates are liquidated.

Seventh, States will take a hit from falling stamp duty as transactions slow. They will not be able to reverse this.

Eighth, Government will try various stimulation moves to try to prop up the market – but persuading people to buy now will be like selling seawater on the beach. They may well provide cash support direct to households for mortgage and rent payments – they probably should.

Ninth – the property wealth effect, which was a mirage, is dead. Finally. Until the next bubble starts, which it will, unless policy changes. I will have more to say about that ahead.

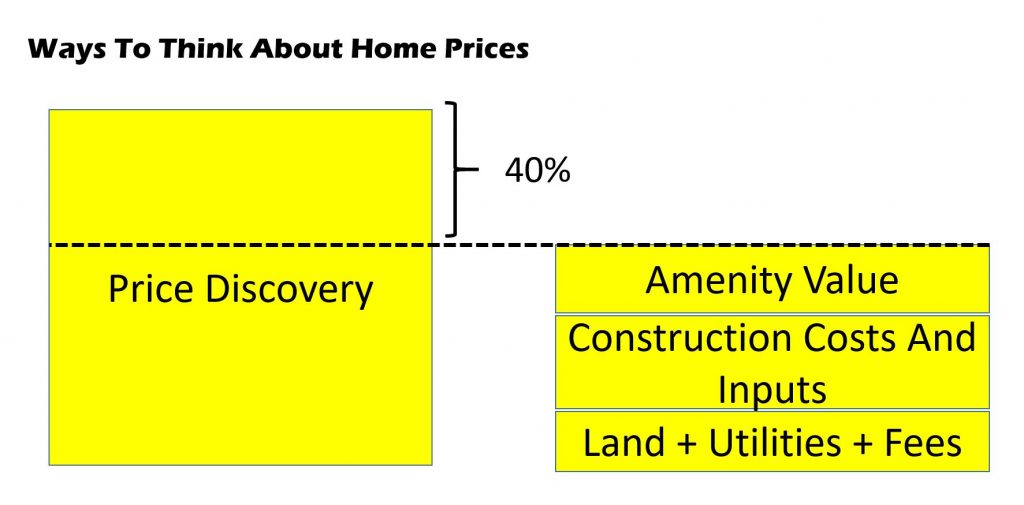

Finally, its worth thinking about this. On average, prices are 40% over their fundamental value. So they have a long way to fall.

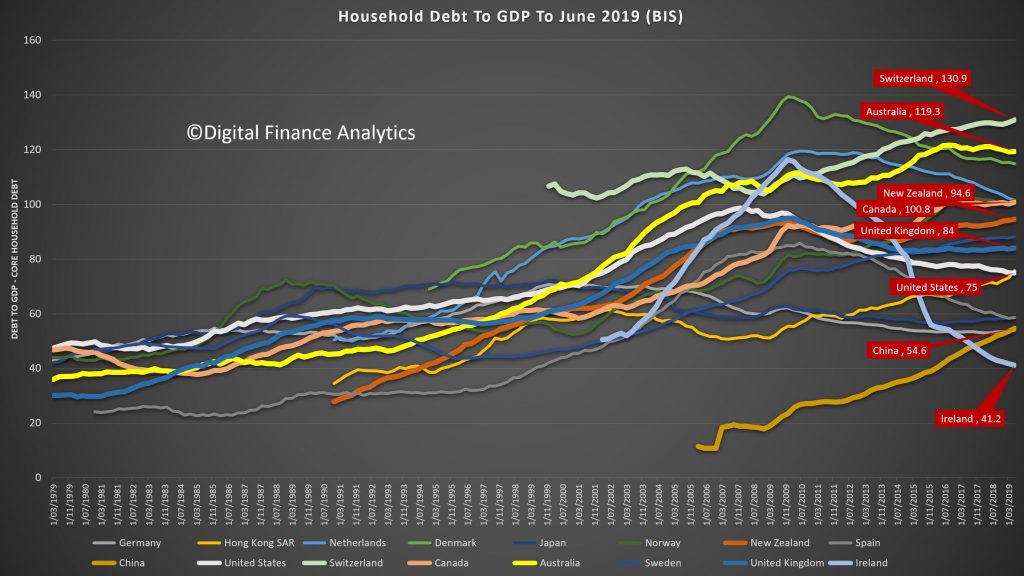

And debt to GDP ratios are, and will go further off the charts.

Tasmania Isolates

From midnight, Friday 20 March, all non-essential travellers departing for Tasmania will be required to quarantine for 14 days, as announced today by Peter Gutwein, Premier. He said:

This is a tough, but necessary decision to flatten the curve, putting Tasmanians’ health and wellbeing first.

The quarantine period will not apply to essential travellers – such as health care workers, emergency workers, defence personnel, air and ship crew, specialists, and essential freight personnel (truck drivers/spirit freight), and there will be stringent guidelines to manage this.

Travel restrictions do not apply to Tasmanian residents on our islands, such as King and Flinders, flying into mainland Tasmania. However they will apply to anyone travelling inbound to the island from mainland Australia including residents returning home to the island. Mainland Australians flying into our islands then onto mainland Tasmania will need to self- quarantine when they arrive.

All passengers will be screened on arrival and must demonstrate they meet the essential traveller criteria.

If they are deemed non-essential, they will be directed to quarantine themselves at their stated place of address. Tasmania Police and Biosecurity Tasmania will ensure compliance with the quarantine measures, helping people to access support and follow up to ensure the process is adhered to.

Breaching the quarantine process may incur a penalty of up to $16,800.

The message is clear, and the penalties are severe for anyone who does not comply with the mandatory quarantine.

Freight will continue to come in and out of our state, and with TT-Line having capacity to carry extra freight, Tasmanians can be assured we will have the essential supplies we need.

Those requiring interstate medical treatment will also be able to utilise the Royal Flying Doctor’s Service.

There is nothing more important than Tasmanians’ safety, and while the economic impact will be significant, we have a chance now to slow the spread of COVID-19 in our state.

This will provide Tasmanians with more certainty, help us to recover more quickly and make our state safer.

Under a State of Emergency, we will activate the State Control Centre, which will be headed by the State Controller (Commissioner of Police, Darren Hine) in close liaison with the Director of Public Health, to coordinate whole-of-government responses to COVID-19.

As an island we are well placed to implement these tough restrictions and slowing the spread of coronavirus will ensure we are better placed to protect all Tasmanians.