I caught up with the founder of Hero Broker, Clint Howen to discuss what he is seeing in the mortgage industry at the moment. The online platform gives an interesting perspective on the changes in the market.

Weaker Environment Exacerbates Challenges for APAC Banks

Global macroeconomic challenges are likely to increase pressure on the short-term earnings prospects of investment-grade banks in the Asia-Pacific, Fitch Ratings says in a new report. The report addresses the main questions asked by US and Canada-based investors during a recent tour by Fitch analysts to discuss mainly investment-grade rated banking systems, with particular focus on Australia, New Zealand, mainland China and Hong Kong, Japan, Korea and Singapore.

Banks in most markets face several challenges to operating performance, including increased costs related to regulation, slower trade and economic growth, subdued loan growth, low interest rates and acute competition. These factors are squeezing net interest margins and overall profitability. However, while many banks are likely to report weaker financial results (or less improvement) in 2020 than in 2019, we do not expect significant deterioration, and there is unlikely to be any immediate impact on ratings. Consequently, the majority of bank ratings remain on Stable Outlook. Nevertheless, some banks in Australia (in particular, the major banks and their New Zealand subsidiaries) and in Japan are more exposed to negative rating pressure. Where this is the case, ratings are on Negative Outlook.

To combat these pressures, banks are increasingly competing for fee income as part of less asset-intensive (or risk-weighted asset-intensive) growth strategies, including boosting total income from key relationships. However, many banks have resorted to taking additional risk, typically credit risk, in search of greater revenue and margin drivers.

Increased risk appetite is appearing in various channels. These include expansion into banking systems in overseas markets where Fitch regards the operating environment as weaker; moving down the credit curve to support loan-yields (through SME lending and unsecured personal lending, for example); holding higher-yielding investment securities; and higher loan concentrations in certain sectors such as property. The latter has been attractive to banks from a risk-adjusted return perspective, but higher concentrations increase the risk of faster deterioration in less-benign operating conditions.

We expect Australia’s major banks to face further earnings pressure in 2020. Falling interest rates and slow credit growth are putting pressure on net interest income, while the sale of parts of the banks’ wealth management operations and a reduction in fees and commissions will hit non-interest income. We expect a modest uptick in impairment charges in the weaker operating environment, with households remaining susceptible to shocks in light of their high leverage, while remediation programmes and system investments will weigh on costs. Furthermore, higher prudential standards in Australia and New Zealand will weigh on overall returns on capital, even though they will support the intrinsic strength of the banks. Australia’s economy is stable but growth is subdued, with downside risk stemming mainly from a weaker global economy and the US-China trade dispute.

Bank ratings in China, Hong Kong, Korea and Singapore remain stable, reflecting either external support (sovereign or institutional) or the banks’ intrinsic financial profiles having adequate buffers at current rating levels to weather expected deterioration in 2020. Nevertheless, downside risks exist, due to external challenges and, in Hong Kong’s case, an economy hit hard by social unrest. Increasing exposure to faster-growing emerging markets is likely to add to pressure, but this may only become more evident when the operating environment is less benign. This is also the case for Japanese banks, and comes on top of structural challenges to their domestic operations, which are likely to continue dragging on earnings and internal capital generation.

Australian economic view – December 2019

Frank Uhlenbruch, Investment Strategist in the Australian Fixed Interest team, Janus Henderson provides his Australian economic analysis and market outlook.

Market review

Australian government bond yields initially followed offshore yields higher on optimism that a trade deal was imminent. However, sluggish domestic economic data and Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) commentary on unconventional monetary policy saw government bond yields end the month lower. Improving sentiment supported equity and credit markets. Overall, the Australian bond market, as measured by the Bloomberg AusBond Composite 0+ Yr Index, rose by 0.82%, with price appreciation from modestly lower yields boosting the income return.

Three and 10 year government bond yields rose to their highs of 0.88% and 1.30% following reports of a ‘Phase 1’ trade deal between the US and China and stronger US services sector data. Yields then rallied as it appeared a trade deal may be delayed and RBA commentary on unconventional monetary policy was seen as dovish. Australian three and 10 year government bond yields ended the month 16 basis points (bps) and 11bps lower at 0.65% and 1.03%.

Australian data releases remained consistent with growth running at a sub-trend rate, with limited signs of recent fiscal and monetary easing boosting domestic demand. Retail sales for September were sluggish, gaining 0.2% over the month but falling by 0.1% in volumes terms over the quarter. While there was an improvement in consumer sentiment in November, confidence levels remain subdued with indications that uncertain consumers are saving rather than spending recent gains from tax rebates and lower mortgage rates.

Despite a small improvement in business conditions in the October NAB Business Survey, both confidence and activity measures remain below longer-run measures and have yet to show signs of a meaningful response to earlier policy stimulus. Consistent with sluggish survey readings, construction work done fell 0.4% in the September quarter, while private capital expenditure fell by 0.2%. This data, along with weak retail sales, point to another quarter of subdued growth in the upcoming release of the September quarter national accounts.

Labour market conditions softened, with employment falling by 19,000 in October, the first fall in 16 months. The unemployment rate lifted from 5.2% to 5.3% and the participation rate fell from 66.1% to a still historically high level of 66%. Wages growth remained modest, with the Wage Price Index lifting by 0.5% over the September quarter for a yearly growth rate of 2.2%. RBA commentary suggests that they expect to see wages growth around these levels persist for some time before lifting as labour market slack is eventually absorbed.

Against the backdrop of sluggish activity and perceived dovish central bank commentary, markets moved to factor in further easing over 2020 after largely ruling out a December move. Markets are assigning a 60% chance of a February 2020 easing and have a 0.50% cash rate fully priced by May 2020. By the end of 2020, markets are assigning a 40% chance of the cash rate falling to 0.25%, the effective lower bound.

Credit markets benefitted from the improvement in trade-related risk sentiment and investors’ ongoing search for yield, with the Australian iTraxx Index rallying 3bps to end the month at 56bps. Primary markets were active as companies looked to finalise debt funding ahead of the end of the year. Notable deals included residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) issued by Bendigo and Adelaide Bank, ING, and CBA, with the latter being the first RMBS deal to replace the historically used Bank Bill Swap Rate (BBSW) with AONIA (Australian Interbank Overnight Cash Rate) as a reference rate for the payment of coupons to investors.

Market outlook

Our base case remains for an extended period of accommodative monetary policy that will only be unwound once the RBA has confidence that inflation will settle in the middle of its target band. The latest set of forecasts from the RBA saw them downgrade their near-term economic growth forecasts by 0.25%, although they left their 2020 and 2021 GDP forecasts unchanged at 2.75% and 3%. With spare capacity being absorbed at a slower rate, the RBA pushed back the timing of when core inflation reaches 2% from mid-2021, to the end of 2021.

While the RBA considered easing monetary policy at its November meeting, it chose instead to join the US Federal Reserve and other central banks in pausing to wait and see how policy easing to date flows through into the broader economy, how trade developments unfold and the extent of any fiscal easing.

The RBA maintains an easing bias and is of the view that further cuts would provide additional net stimulus. In a landmark speech, the RBA Governor signalled that a 0.25% cash rate reflected the effective lower bound for the cash rate. The Governor saw negative interest rates in Australia as extraordinarily unlikely.

If further support for the economy was required when the cash rate was at the lower bound, then the RBA would consider unconventional policy measures, with the main focus on purchasing government bonds, including state government bonds, from the secondary market to drive down the risk-free rate that affects all asset prices and interest rates in the economy. If such policy support was required, the Governor noted that a combination of policy responses, including fiscal, would deliver the best results.

With little signs of recent policy stimulus and a turnaround in house prices showing up in activity, labour market and confidence indicators, we look for a further rate cut in February 2020 which would take the cash rate down to 0.50%. The prospect of the Government bringing forward ‘Phase 2’ tax cuts worth around $13.5bn in the May 2020 Budget, which would come into effect on 1 July 2020 , would significantly reduce the burden on monetary policy and rule out the need for a further cash rate cut and unconventional measures. This is our central case view and we see the stimulus from these measures raising the prospect of the cash rate lifting over the latter part of 2022.

We see nearer term risks tilted towards our low case scenario, where the cash rate falls to 0.25% and a lack of fiscal easing forces the RBA to initially extend its forward guidance. A lack of a coordinated policy response would see the RBA embark on a government debt purchase programme that flattens the domestic yield curve. Overall, we see three and 10 year government bond yields of 0.66% and 1.05% (at the time of writing) as offering little opportunity to express strong views on duration.

We continue to remain attracted to maintaining a core exposure to inflation-protected securities in an environment where policy is being firmly directed to boosting growth and lifting inflation back towards central bank targets. Despite a modest and ongoing lift in breakeven inflation rates from the record low levels experienced in late August, current pricing suggests markets still have little confidence that recent policy moves will gain much traction. However, with the cost of buying inflation protection now so low, we feel it makes sense to position for the prospect of a cyclical lift in inflation over the next few years, especially if one contemplates even more extreme policy measures to reflate economies.

Is a cashless society worth it?

As the country continues its inexorable march towards a cashless society, it’s important to remember the downsides. Via The Adviser.

Australia has been just a few years away from being a cashless society for a couple of decades now, but it will eventually get there. Legislation currently before the Senate aims to ban transactions over $10,000 in a bid to hinder the black economy. From there, it’s not difficult to imagine that the ubiquity of digital payment systems – and efforts the by government – will see hard cash disappear at some point in the future.

One of the supposed benefits of a cashless society is that it cuts down on crime, the logic being that if there’s less cash to steal, less cash is stolen. Laundering dirty money is also harder, as every transaction is logged in some form or another.

But a cashless society comes with a number of negatives that might well outweigh the positives.

“As payments move online, there would be an increased risk of crimes such as identity theft, account takeover, fraudulent transactions and data breaches, due to the higher volume of cashless transactions and more points of exposure for the average consumer,” Dr Richard Harmon, managing director of financial services at Cloudera, told Investor Daily.

“Hackers and other criminals now have new ways to get access to accounts and to potentially set up synthetic accounts to facilitate more sophisticated money laundering activities.”

And that’s just the risk posed by hackers. According to the UK’s access to cash report, a cashless society could heighten the risks of financial abuse. Elderly people, who might lack understanding of digital technology, would be particularly vulnerable. Couples with joint bank accounts are also at risk – money can be tracked and controlled by one person. These issues are already of great concern, but they’d be even worse in a cashless society.

That’s not to mention that digital systems rely on topnotch digital infrastructure, something that Australia doesn’t exactly have in spades. That infrastructure also has to be more or less impervious to cyber attacks, which may be carried out by state-sponsored actors with an interest in crippling a country’s entire financial system. In the face of that existential threat to the economy, a little bit of money laundering doesn’t seem so bad.

A cashless society could also make things worse for workers and the most vulnerable. It’s only a short jump from cashless to “cashier-less”, and a cashless society would have to deal with an explosion of unemployed low-skill individuals.

Meanwhile, those who lack access to banks – or prefer not to use them – are also at risk.

“Let me highlight that one of the concerns about becoming a cashless society – at least as we transition into this state – is the ability for the underbanked or unbanked to have sufficient access to function properly as they would within a cash-based system,” Dr Harmon said.

“This would be a key concern from a societal perspective.”

The idea of a cashless society is promising. But hidden in that promise are a number of caveats that any country – let alone Australia – would be foolish to ignore.

Data, Data, Everywhere; Nor Any Drop To Drink! [Video]

The latest economic data confirms the pressures on households and the broader economy are real.

RBNZ Imposes Higher Capital

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand today released its final decisions following its comprehensive review of its capital framework for banks, known as the Capital Review. The trajectory will be over a longer period, with more flexibility, but the banks will still need to hold more capital.

Governor Adrian Orr said the decisions to increase capital requirements are about making the banking system safer for all New Zealanders, and will ensure bank owners have a meaningful stake in their businesses. The changes will be implemented over seven years, giving plenty of time for banks to manage a smooth transition and minimise any adjustment costs.

“Our decisions are not just about dollars and cents. More capital in the banking system better enables banks to weather economic volatility and maintain good, long-term, customer outcomes,” Mr Orr says.

“More capital also reduces the likelihood of a bank failure. Banking crises cause not only harmful economic costs but also distressful social issues, such as the general decline in mental and physical health brought about by higher rates of unemployment. These effects are felt for generations,” Mr Orr says.

The key decisions, which start to take effect from 1 July 2020, include banks’ total capital increasing from a minimum of 10.5% now, to 18% for the four large banks and 16% for the remaining smaller banks. The average level of capital currently held by banks is 14.1%.

Relative to the Reserve Bank’s initial proposals, the final decisions also include:

- More flexibility for banks on the use of specific capital instruments;

- A more cost-effective mix of funding options for banks;

- A lesser increase in capital for the smaller banks consistent with their more limited impact on society should they fail;

- A more level capital regime for all banks – with the four large banks having to measure the risks of their exposures (lending) more conservatively, more in line with the smaller banks; and

- More transparency in capital reporting.

The adjustments to the original proposals reflect our analysis and industry feedback over the past two years. All of these changes will be phased in over a seven-year period, rather than over five years as originally proposed, in order to reduce the economic impacts of these changes.

Deputy Governor and General Manager of Financial Stability Geoff Bascand says the decisions were shaped by valuable public input and insight received through an unprecedented number of submissions as well as public focus groups. Three international experts also provided supportive perspectives on the proposals.

“We’ve listened to feedback and reviewed all the data, and are confident the decisions are the right ones for New Zealand,” Mr Bascand says.

“We have amended our original proposals in a number of ways so we achieve a high level of resilience at lower potential cost, with a smoother transition path for all participants. Our analysis shows that the benefits of these changes will greatly outweigh any potential costs.”

“Following the Global Financial Crisis, many regulators around the world have been taking steps to improve the safety of their banking systems. We’re confident we have the calibrations right for New Zealand conditions. These changes will be subject to monitoring, with the Reserve Bank reporting publicly on implementation during the transition period,” Mr Bascand says.

APRA proposes major uplift in transparency around banking data

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has proposed substantially increasing the volume and breadth of data it makes publicly available on authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs), including banks, credit unions and building societies.

The move towards greater transparency and scrutiny of the banking sector is aimed at increasing accountability, supporting competition and lifting overall industry standards.

In a letter to industry today, APRA outlined plans to determine that all data collected for its quarterly ADI publications should be considered non-confidential, allowing it to be published. APRA currently publishes less than 1 per cent of the ADI data it collects due to legal restrictions contained within the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Act 1998 (APRA Act). This change would allow APRA to significantly increase this figure.

From 2020, APRA proposes publishing:

- entity-level ADI data related to currently published industry-level quarterly data;

- remaining historical data in these forms that individual ADIs are required to provide APRA, which will be published with a three-year lag; and

- commentary received by APRA from individual ADIs explaining material revisions to, or large movements in, their data.

The proposal supports

APRA’s strategic policy of increasing the transparency of data it collects, and

aligns with Government open data policies.

APRA’s Executive Director for Cross-Industry Insights and Data, Sean Carmody,

said: “APRA is committed to increasing transparency about the institutions and

industries we regulate.

“Under these proposed changes, APRA intends to publish – for the first time – a

range of information about individual ADIs, including their financial

performance and property exposures.

“As with the recent inclusion of data from credit unions and building societies

in our Monthly ADI Statistics publication, these changes are aimed at further

strengthening the ADI sector by enhancing accountability and encouraging

competition. They will also assist other regulatory agencies that rely on APRA

data, as well as analysts, policymakers and others who use our publications.”

Under the APRA Act, APRA must consult ADIs and their representatives, including

industry associations, before determining any new data to be non-confidential.

A 12 week consultation is now underway and concludes on 28 February 2020. APRA

is encouraging all interested parties to make submissions on issues including

what, if any, data should remain confidential.

APRA intends to consult on forms not included in this consultation at a later

date.

More details on the consultation, including the letter to industry, can be

found at: https://www.apra.gov.au/confidentiality-of-data-used-adi-quarterly-publications-and-additional-historical-data

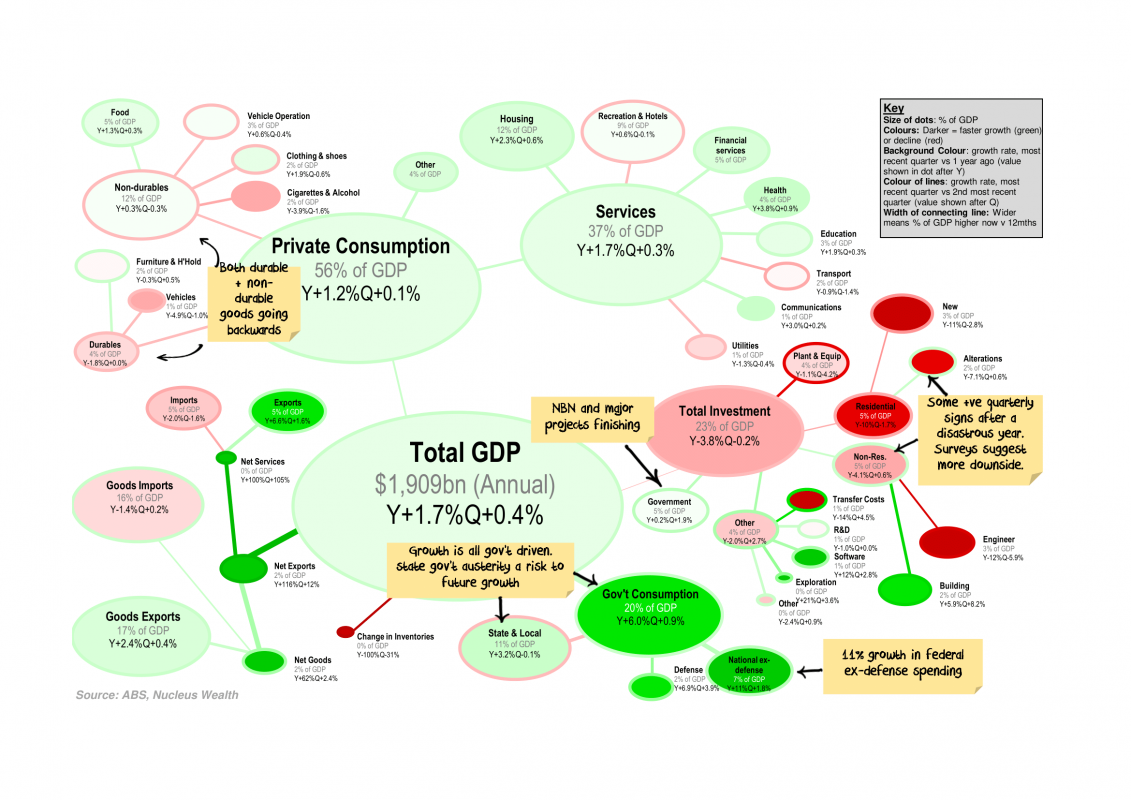

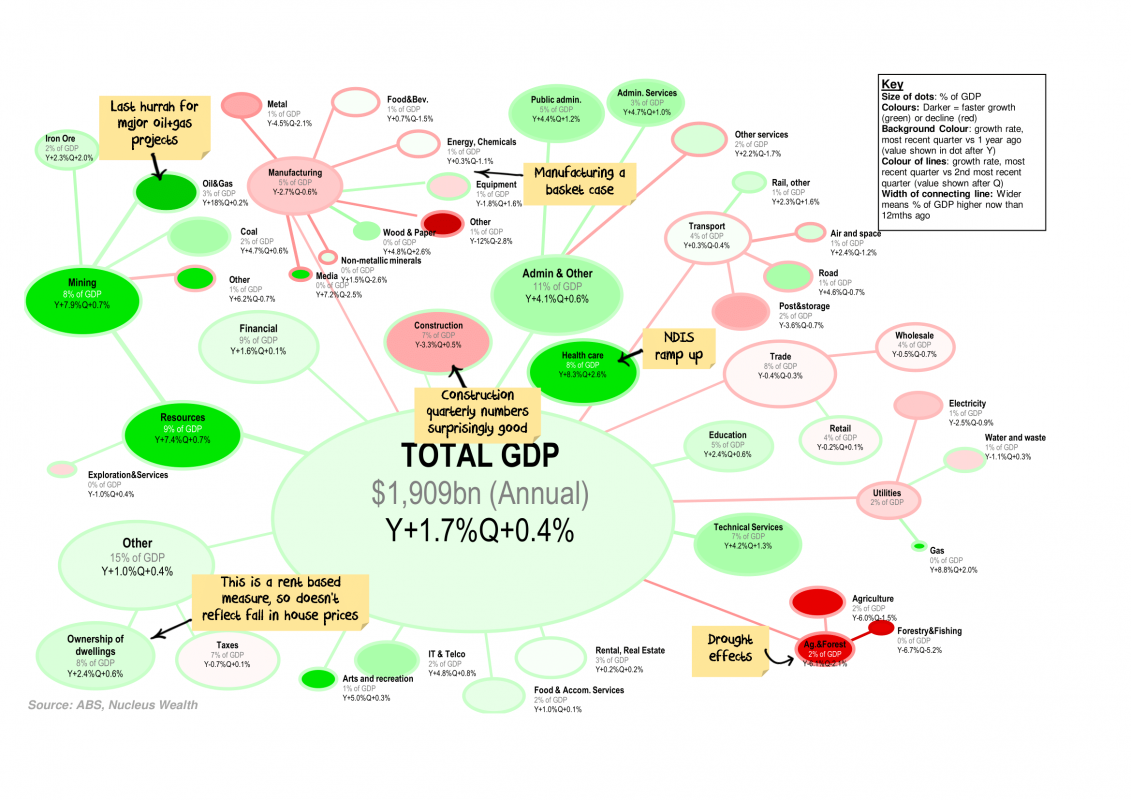

GDP Hotspots

Courtesy of Nucleus Wealth’s Damien Klassen. Damien runs the investment side of Nucleus, selecting stocks suggested by analysts and implementing the asset allocation

Every quarter I like to look at the changes in Australian GDP and which categories are responsible for the growth / decline. Each bubble represents a category of GDP proportionate to its size, colours represent the growth rate.

Click the charts for a large version and commentary:

This quarter the key takeaways include:

- Federal Government spending (+11% for non-defence, 7% for defence over the year) the only thing keeping GDP above zero.

- Investment growth was not good, but I was expecting worse. Possibly there are green shoots, but capex surveys and investment forward indicators suggest there is still more downside.

- State & Local government spending has turned negative – with a low number of property transactions this is likely to remain a feature

Retail Turnover Nowhere

Australian retail turnover was relatively unchanged (0.0 per cent) in October 2019, seasonally adjusted, according to the latest Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Retail Trade figures. The retail recession continues, and now the question becomes, will the summer holidays and Christmas change anything ahead?

This follows a rise of 0.2 per cent in September 2019.

“There were falls for clothing, footwear and personal accessory retailing (-0.8 per cent), department stores (-0.8 per cent) and household goods (-0.2 per cent),” said Ben James, Director of Quarterly Economy Wide Surveys.

“These falls were offset by rises in cafes, restaurants and takeaway food services (0.4 per cent) and food retailing (0.1 per cent). Other retailing was relatively unchanged (0.0 per cent).”

In seasonally adjusted terms, there were mixed results across the states. Victoria (-0.4 per cent), New South Wales (-0.2 per cent), and South Australia (-0.5 per cent) fell, while Queensland (0.4 per cent), Tasmania (1.4 per cent), the Northern Territory (2.3 per cent), Western Australia (0.2 per cent), and the Australian Capital Territory (0.3 per cent) rose in seasonally adjusted terms in October 2019.

The trend estimate for Australian retail turnover rose 0.2 per cent in October 2019, following a 0.2 per cent rise in September 2019. Compared to October 2018, the trend estimate rose 2.3 per cent.

QE could drive populism rather than the economy

The Reserve Bank will consider quantitative easing once rates fall to 25 basis points. It’s a tool that has been used by other countries, often with devastating consequences for society. Via InvestorDaily.

Australia is in uncharted territory, economically speaking. We’re latecomers to the low-rate party and we’re still getting used to it. Home owners are loving it but retailers are not. Unemployment is low but a record number of Aussies want to work more. It’s a strange time.

The Reserve Bank of Australia only has a few options left if it fails to hit its inflation target and lift economic growth. It can continue to reduce the cash rate and even go into negative rates, as the European Central Bank (ECB) had done. The ECB benchmark deposit rate was cut by 10 basis points in September to negative 0.5 per cent. The ECB also reintroduced its quantitative easing program of buying 20 billion euros ($32 billion) worth of government and corporate bonds every month in an effort to prevent the European economy from sliding off a cliff.

The ECB has been using QE on and off since 2009 in an effort to lift inflation. In 2015 the central bank began purchasing 60 billion euros worth of bonds each month. This increased to 80 billion euros in April 2016 before coming back down to 60 billion a year later.

In the UK, the Bank of England bought gilts (British government bonds) and corporate bonds during its QE program during the global financial crisis in 2009. QE programs also took place in 2011 and 2016.

Meanwhile, the US Federal Reserve has undertaken three separate rounds of QE, the last of which it began tapering in June 2013. The US halted its program in October 2014 after acquiring a total US$4.5 trillion of assets.

When a QE program takes place, a central bank begins buying securities with money that didn’t exist before the QE process began. They are essentially printing money and giving it to large corporates and the government through the purchase of these bonds, the logic being that the proceeds will be used to buy new assets (like mortgages) and invest, which in turn will drive the economy.

The money doesn’t directly hit the wallets of consumers. Unlike “helicopter money”, which the Rudd government dished out during the financial crisis, QE has a much more indirect impact on consumers. Financially speaking.

But the broader political and social impacts have had a lasting psychological effect on the populations of Europe and the US.

“If we look at the experience offshore, QE has been great at raising the level of assets in conjunction with a permanently lower interest rate,” Fidelity International’s Anthony Doyle said this week.

“QE has stimulated asset price growth. The ‘haves’ have benefited compared to the ‘have nots’; income inequality has grown across the economies that have implemented quantitative easing and socially we have seen big shifts to the Right or to the Left in terms of the political spectrum.

“If you think about Donald Trump, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Brexit, Boris Johnson. The next decade could be characterised by moves to the Right or Left here as well if we follow a path that other economies have pursued.”

AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver told Investor Daily that QE “probably helps people who have shares and property more than it does people who have bank deposits.”

Prior to the election of Mr Trump in 2016, Luis Zingales of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business told Bloomberg that central bank policies are largely to blame for the rise of populism.

Here in Australia, the Reserve Bank will have to consider the impact that QE could have on a society that has witnessed a banking royal commission that exposed widespread misconduct within the financial services industry.

If the impact on Europe and the US of QE on the people is anything to go by, Australia is well placed to split down the middle and begin gathering on the far edges of the political spectrum.

We were late to the low rate party. We might just be late to the populism party too.