We look at the last business surveys.

The Future Of Your Savings!

We examine a recent article which highlights how Central Banks are crushing savers.

CBA Trading Update Sep 19: OK But…

CBA, who is on a different reporting cycle to the other majors, released their trading update to 30th September 2019 today. These are unaudited numbers and included some one-off items, but generally it looks like CBA managed to navigate the complexities of the current market quite well. But its all a matter of relativity as all the banks remain under pressure.

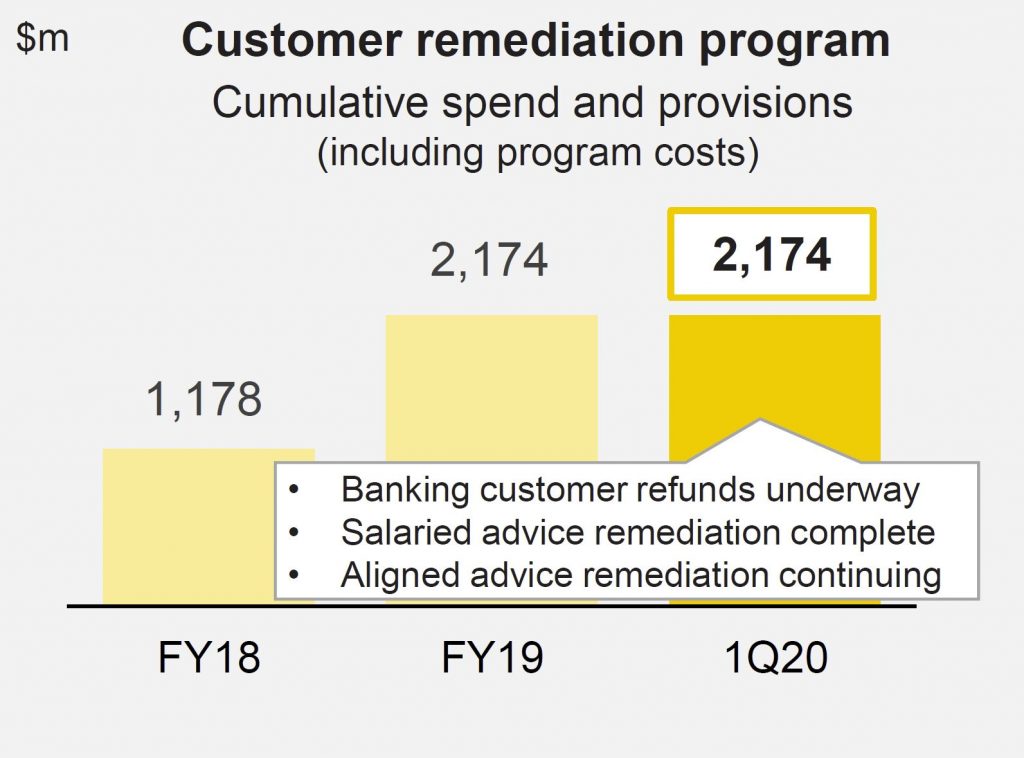

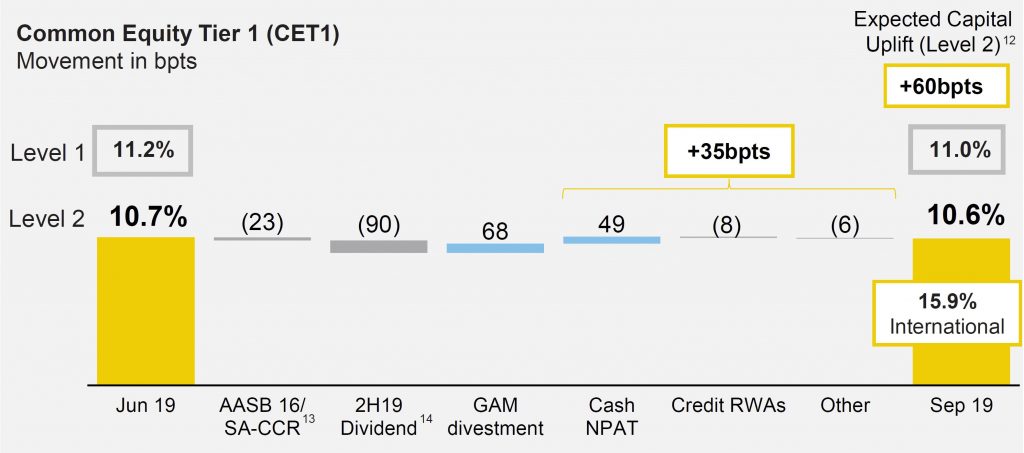

That said, the CET1 ratio was down, there was a considerable increase in corporate troublesome assets (discretionary retail, construction and agriculture), plus pockets of stress across its personal loans portfolio in Western Sydney and Melbourne. The Net Interest Margin was “lower than June 2019 due to headwinds associated with a low interest rate environment, which will continue to impact margins in future periods”. $2.2bn is flagged for customer remediation in program spend and provisions.

They made comparisons with the average of the previous two quarters, which might flatter the results a little. And they may have been later to implement the revised tighter HEM, which might have flattered their loan growth. Overall capital risk wights for mortgages sat at 25.8%.

Worth also noting that according to Banking Day:

Commonwealth Bank was the subject of the highest number of complaints to the Australian Financial Complaints Authority over the year to June, with the other big banks not far behind.

CBA was way out in front, with 3,890 complaints. ANZ, at number two, received more than 1,000 fewer complaints.

Unaudited statutory net profit was around $3.8 billion in the quarter, but this included a $1.5 billion gain from the sale of Colonial First State Global Asset Management(CFSGAM) to Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking Corporation, with a post-tax gain on sale of approximately $1.5 billion.

Net cash profit from continuing operations was around $2.3 billion, up 5% excluding one-offs. This is the figure they want you to focus on!

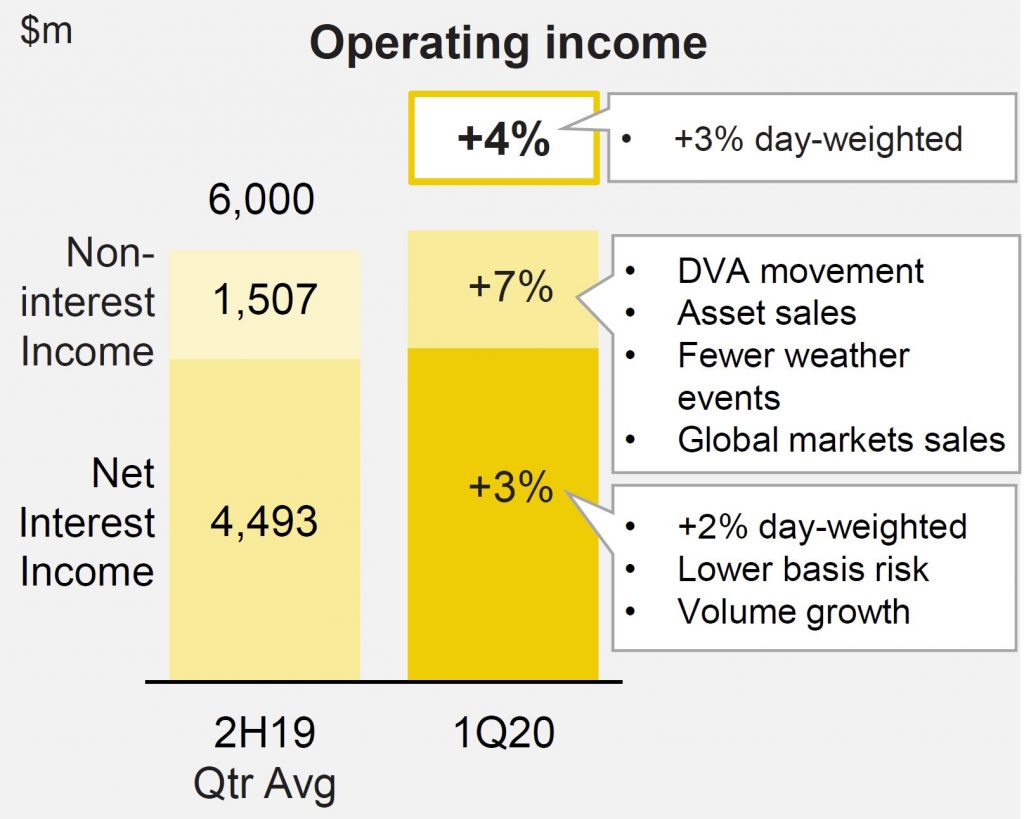

Operating income was up 3% (day-weighted)

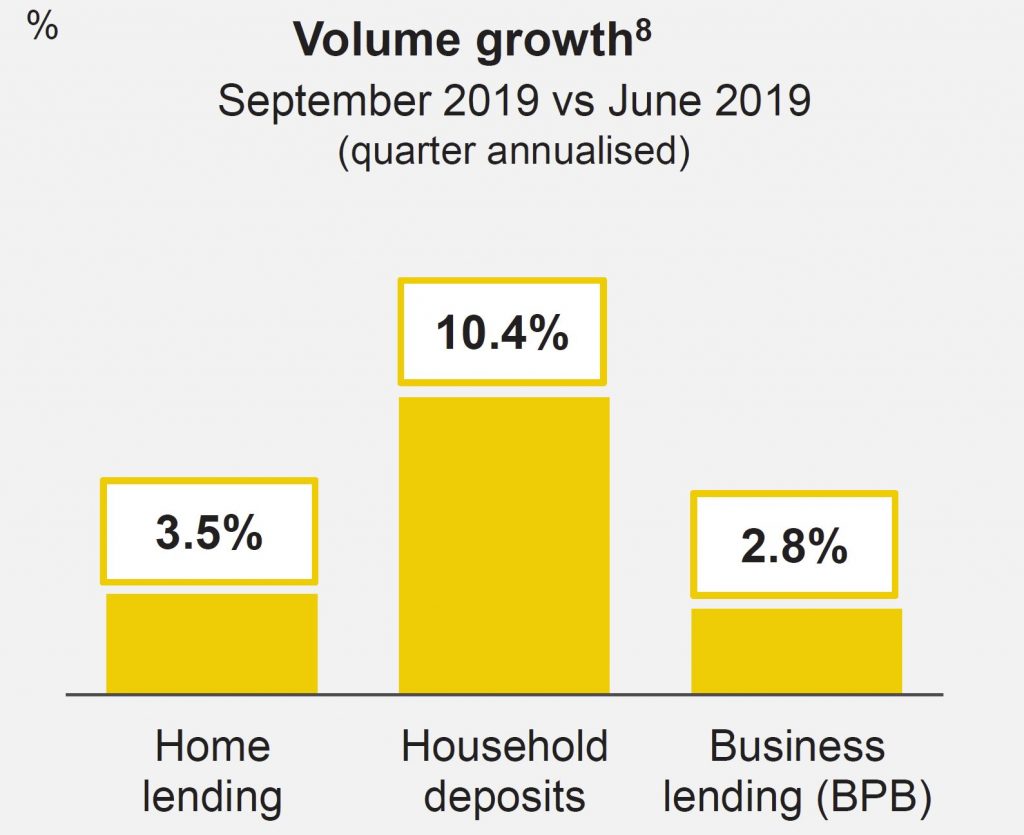

Net interest income increased 3%, benefiting from 1.5 additional days in the quarter. On a day-weighted basis, Net Interest Income was 2% higher, underpinned by volume growth in core markets of home lending, business lending and household deposits.

Excluding a 4 bpt benefit from lower basis risk, the Group’s Net Interest Margin was lower than June 2019 due to headwinds associated with a low interest rate environment, which will continue to impact margins in future periods.

Non-interest income increased 7%, benefiting from timing differences and one-off items including a favourable movement in the derivative valuation adjustment (DVA), asset sales in Structured Asset Finance (SAF), higher insurance income from fewer weather events/claims and higher global markets sales. These were partly offset by lower Funds Management income and the ongoing impact of the Bank’s Better Customer Outcomes program, which continues to deliver customer savings equivalent to annualised income forgone of $415m.

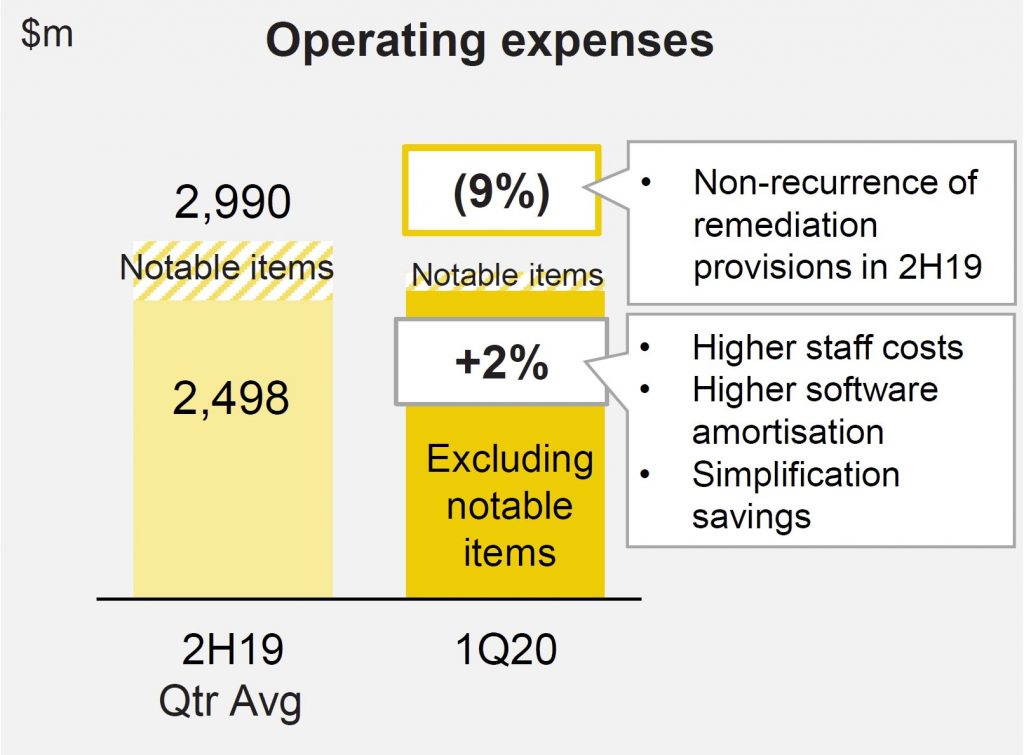

Operating expenses were up 2% (excluding notable items), reflecting higher staff costs and IT amortisation.

Customer remediation continues to drag the results. Of the $2.2bn in total program spend and provisions, $1.2bn relates to customer refunds of which approximately $600m has been paid to banking and wealth management customers to-date (ex aligned advice). Salaried adviser ongoing service remediation is now complete and represented a refund rate of 22% (ex interest). Aligned advice remediation work relating to ongoing service fees charged between FY09 and FY18 is continuing. The aligned advice remediation provision recognised in FY19 of $534m included program costs of $160m, $251m in customer refunds and $123m in interest. This assumed a refund rate of 24% (ex interest) and36% (incl.interest).

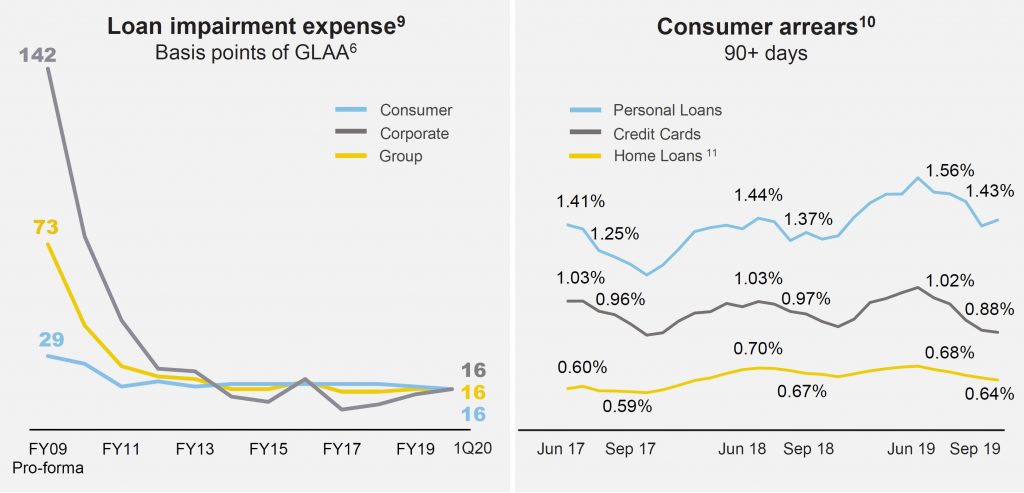

Loan Impairment Expenses were $299m in the quarter equated to 16bpts of Gross Loans and Acceptances, unchanged onFY19.

Consumer arrears improved in the quarter due to seasonality and the benefit of higher tax refunds. Personal Loan arrears rates remained elevated due to lower portfolio growth and continued pockets of stress in Western Sydney and Melbourne.

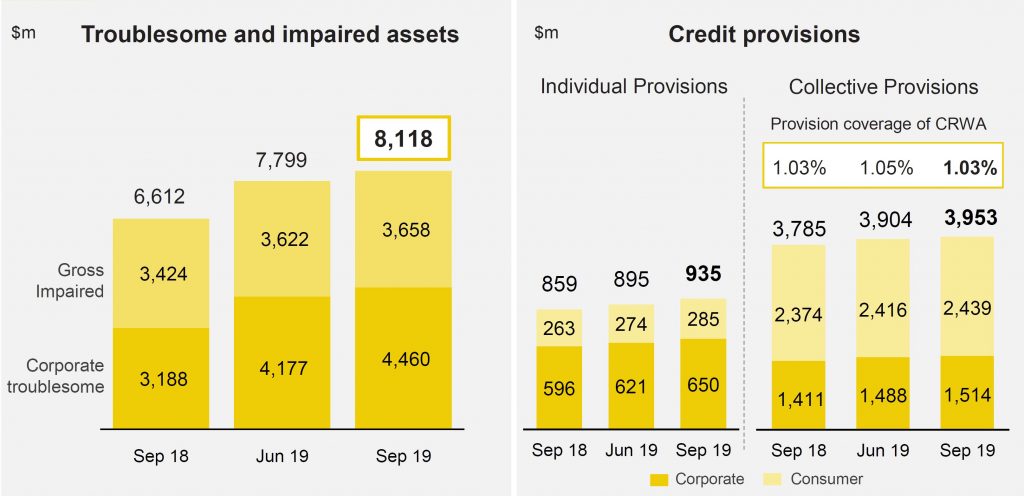

Troublesome and impaired assets increased to approximately $8.1bn. Corporate Troublesome assets continued to reflect weakness in discretionary retail, construction and agriculture,as well as single name exposures.

Total provisions increased by $89m to approximately $4.9bn.

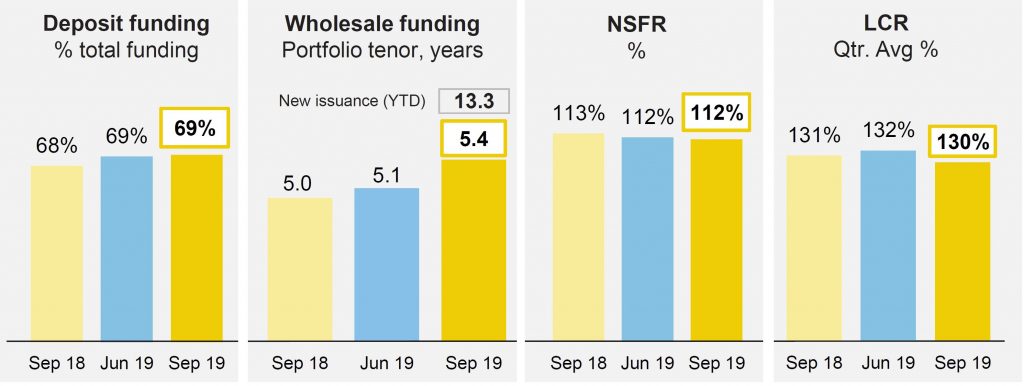

Customer deposit funding was at 69% and the average tenor of the long term wholesale funding portfolio at 5.4 years. The Group issued $5.8bn of long term funding in the quarter, including two long-dated Tier 2 transactions following the release of APRA’s loss-absorbing capacity proposal in July2019, contributing to a weighted average maturity of new issuance in the quarter of 13.3 years.

The Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) was at 112%, the Liquidity Coverage Ratio(LCR) at 130% and the Group’s Leverage Ratio at 5.5% on an APRA basis (6.4%internationally comparable).

The Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) APRA ratio was 10.6% as at 30 September 2019. After allowing for the impact of the 2019 final dividend and one-off impacts from regulatory changes and the CFSGAM divestment, CET1 increased 35bpts in the quarter. This was driven by capital generated from earnings, partially offset by higher Credit Risk Weighted Assets driven by revised regulatory treatments and lending volume growth. As at 30 September 2019, the Level1 CET1 was 11.0%, 40bpts above the Group’s Level2 CET1 Ratio.

The Group’s remaining previously announced divestments are expected to collectively provide an uplift to Level2 CET1 of approximately 60bpts. As outlined in the Group’s FY19 results, a strong expected capital position creates flexibility for the Board in its consideration of capital management initiatives.

Did The End Of The World Just Get Postponed?

Something happened late last week, which superficially might be attributed to positive news on the US China trade talks (later downplayed by Trump) but it was wider and more significant than that.

In recent months many traders have been positioning for a significant market correction, and potentially a US or global recession. Thus, risk stocks were downplayed, while bonds and gold were all the rage.

This drove the yields on bonds down, to the point where in several countries, like Germany they went negative, and at its peak, it was estimated that around $17 trillion of bonds were effectively underwater. A couple of weeks back, we pointed out that Gold had shot ahead of itself, and that the Gold futures meant it would slide. It did, falling by more than $30 an ounce.

The 10-year US Treasury yield rose on Friday to 1.94%. up nearly 50 basis points from the lows at the end of August. Remember that the Fed cut its interest rate target twice, by a total of 50 basis points, and short-term Treasury yields have fallen by about that much. With the one-month yield now down to 1.56% and the 10-year yield up at 1.94%, the yield curve has un-inverted and steepened. Recession has been postponed, for now.

Germany’s 30-year bonds are interesting in that they tried to sell them at a negative yield of -0.11% on August 21, with a 0% coupon – so no interest payments for 30 years – and at a premium, in order to achieve the negative yield of -0.11%. While €2 billion of these bonds were offered, only €824 million were sold. And those investors may rue the day they bought.

We discuss the underling issues.

Does Monetary Policy Work Any More?

In its quarterly statement on monetary policy, released today, the Reserve Bank of Australia declared its preparedness to “ease monetary policy further if needed”. Via The Conversation.

This suggests the bank still thinks monetary policy – in this case lowering interest rates to stimulate the economy – could help “support sustainable growth in the economy, full employment and the achievement of the medium-term inflation target”.

But in the wake of the bank last month lowering the official interest rate to a record low and the current somewhat sad state of the Australian economy, many commentators have speculated that monetary policy doesn’t work any more.

Is that right?

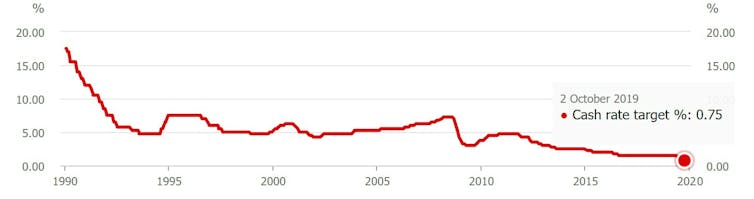

Reserve Bank cash rate

There are a number of variants of the “monetary policy doesn’t work” argument. The most basic is that the Reserve Bank has this year cut rates from 1.50% to 0.75% without any improvement to the Australian economy.

This is a textbook example of one of the classic logic fallacies known as “post hoc ergo propter hoc” (from the Latin, meaning “after this, therefore because of this”).

Put simply, it assumes the rate cuts have had no effect and doesn’t account for the possibility things might have been worse had there been no cuts.

Things might have been even worse. We’ll never know.

It also ignores what might have happened if the RBA had cut sooner. Again, we can’t know for sure. It is possible, though, to make an educated guess.

When to cut rates

Had Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe acted, say, 18 months earlier to cut rates, he would have signalled that Gross Domestic Product growth was indeed lower than desired, that the sustainable rate of unemployment was more like 4.5% than 5%, and, most importantly, that he understood the need to act decisively.

That would have sent a powerful signal.

It would also have ameliorated the huge decline in housing credit that pushed down housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne by double digits.

That, in turn, would have prevented some of the weakening in the balance sheets of the big four banks that has occurred (witness this annual general meeting season).

All of this would have pumped more liquidity into the economy and put households in a much stronger position, likely leading to stronger consumer spending than we have seen.

Bank pass through

One gripe both the Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe and federal treasurer Josh Frydenberg have had with the banks is their failure to fully pass through the RBA cuts.

It is true there is a problem with banks not being able to cut deposit rates below zero, and as a result having less scope to cut mortgage rates, which are majority funded from deposits.

But there are, of course, other ways monetary policy can work. The leading example is quantitative easing (QE).

This is where the central bank pushes down long-term interest rates by buying government and corporate bonds. At the same time this expands the money supply, thereby adding some upward inflationary pressure.

There is little reason to think such measures wouldn’t work.

The power of free money

Perhaps paradoxically, the closer interest rates get to zero the more powerful those rates may end up being.

To put it bluntly, if someone shoves a pile of money into your hand and asks almost nothing in return, you’re likely to use it. In fact, you would be pretty silly not to.

Suppose your mortgage rate really goes to zero – as has happened in Europe.

You might decide to redraw that and spend the money on a home renovation or some other productive purpose. Or you might decide to buy a more expensive house.

Such spending provides an economic boost.

The effect is all the more pronounced if people expect interest rates to be low for a long period of time. Aggressive cutting coupled with quantitative easing – which lowers long-term rates – signal just that.

But not only monetary policy

Just because monetary policy still has some effect at near-zero rates doesn’t mean we should pin all of our economic hopes to it.

A near consensus of economists have argued repeatedly for the use of more aggressive fiscal policy – including more infrastructure spending and more tax cuts.

Indeed, Philip Lowe has raised eyebrows by speaking so forthrightly on this issue. That doesn’t make him wrong, though.

There is little doubt the Reserve Bank should have acted much earlier to cut official interest rates. There is also a very good chance it will need to begin to use other measures such as quantitative easing in the relatively near future.

All of that says the Australian economy, like most advanced economies around the world, is in bad shape.

But it doesn’t mean monetary policy has completely run out of puff.

Author: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

Final Reminder – Harry Dent Will Be In Town Soon

A couple of weeks back I caught up with Harry Dent, the famous economist and author. We discussed the current economic situation, and his view of the potential for an upcoming crash. Here is the show in case you missed it.

There is still time, as a valued-add, to secure up to 2 complimentary tickets to Harry’s Australian events. Note: I get no benefit from publicizing these events, but Harry is always good value .

Melbourne: November 17th-18th

Sydney: November 19th-20th

Brisbane: November 21st-22nd

Perth: November 24th-25th

You can secure your complimentary tickets here. I’ve only been given a total of 50 complimentary tickets to give away and once they’re gone, they’re gone.

30,000 And Counting..!

Thanks to the community we have reached 30,000 subscribers on YouTube.

I really appreciate your support and participation. Here’s to the next 20,000!

What I Said To The Senate On The Restrictions On The Use Of Cash Bill

I outline my submission made to the Senate Inquiry, which is open until next Friday 15th November 2019.

https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Economics/CurrencyCashBill2019

Here is the full text of my submission.

Currency (Restrictions on the Use of Cash) Bill 2019

I have carefully reviewed the latest iteration of this legislation and am gratified that the Senate has chosen to review the proposals, which I strongly oppose.

Not only is the bill significantly eroding our civil liberties, but the conduct of Treasury needs to be called out by suggesting that 3,400 of the 3,500 submission they received during their brief 2 week exposure review submission period were part of a campaign “by the CEC, a political party”. While there was indeed a campaign to oppose the draft legislation, I have evidence that submissions were made by many concerned individuals and businesses with no links to the CEC. Indeed, my own submission, some of the contents I am using here again, is based on my own independent research and analysis. I have no financial or political association with said CEC. I believe Treasury tried to play down the considerable opposition which exists within the community. This bill is, in my view toxic.

Digital Finance Analytics is a boutique research and analysis firm specialising in the financial service sector. We undertake primary research through our surveys, as well as deep research from the global literature relating to financial services. We publish regularly via our online channels at Digital Finance Analytics[1] as well as preparing reports on a range of related subject matters for our clients, and we collaborate with a number of academics.

My objections are centred around the following points.

- Civil Liberties Are Being Eroded. Further public debate on these measures are warranted as they are fundamentally restricting personal freedoms. Today I can use and hold cash as I please. If passed, my freedom will be eroded. This is one in a series of measures which have been taken (including media freedoms) which are curtailing the hard-won freedoms Australians used to enjoy. Public hearings should be held by the Senate to judge community reactions to the bill as part of the current review.

- There Is No Cost Benefit. The stated objective of the bill is to close tax avoidance and money laundering loopholes. But there is no quantification of the potential “savings” – and this is also true of the earlier Black Economy Taskforce report. It appears that simply stating these desired objectives is seen as sufficient to justify the bill. What is the cost benefit of such a measure, bearing in mind that transactions which fall outside the exemptions would need to be tracked and examined?

- Increased Surveillance Will Be Required. In some form, monitoring of offending transactions would be required if the Bill were passed. This is not explained, nor how it would be policed. Who would police them, at what cost? Further, the bill proposed a draconian set of penalties designed to deter. Treasury admitted this in their FOI’d response.

- Existing Laws Are Not Enforced. The true size of the black economy is much in dispute, but indications are that it is already falling. In addition, much of the tax leakage and avoidance would be covered by existing legalisation if it were being policed effectively. We support the view, recently aired by Andrew Wilkie in the debate on the floor of the house, that:

“There’s already a requirement to report transactions over $10,000. The problem is that those laws are not being implemented and enforced[2].”

- There are other more pressing areas of tax leakage and AML risk. According to the OECD report “Implementing The OECD Anti-Bribery Convention” released as part of the OECD Working Group on Bribery, Real Estate is identified as at “significant risk” of being used for money laundering. Among a raft of recommendations, is one saying Australia should be “Taking urgent steps to address the risk that the proceeds of foreign bribery could be laundered through the Australian real estate sector. These should include specific measures to ensure that, in line with the FATF standards, the Australian financial system is not the sole gatekeeper for such transactions”. To date these loopholes, remain open, as do those relating the corporates and big business who, partly thanks to the assistance of the large international accounting firms are responsible for the lions share of tax leakage and AML activity. Our research suggests that Government, under heavy corporate and business lobbying is deliberately letting this slide, preferring to target in on a relatively inconsequential area of tax leakage relating to cash transactions.

- The Legislation Would Be Ineffective. Beyond that, it is clear from our wider research of a range of sources that such a proposed cash ban would have very little impact on hard core tax leakage. For example, Professor Fredrich Schneider, a research fellow at the Institute of Labor Economics at the University of Linz, Austria, a leading international expert on the black economy has stated that there is a lack of empirical evidence that cash transaction bans will help reduce the black economy. Schneider published a paper in 2017[3] “Restricting or Abolishing Cash: An Effective Instrument for Fighting the Shadow Economy, Crime and Terrorism” in which he made this specific point.

- There Is Another Agenda. In addition, while the Bill is silent on the connection to implementing negative interest rates as part of unconventional policy, the link was made clearly in the 2016 Geneva Report by the International Centre Monetary and Banking Studies (ICBM) titled: What else can Central Banks do?[4] This paper which was drafted by officials from international organisations such as the IMF/BIS and multiple central banks + commercial banks. In addition, within the original Black Economy Taskforce Report there was mention of the benefits of a cash transaction ban in relationship to monetary policy – yet this link was denied by Treasury in their recent FOI release.

- The IMF Shows Why. The same thematic came through in recent IMF Blogs and working papers. In April 2019, the IMF published a new working paper on how deeply negative interest rates work. In previous papers, the IMF has suggested that nominal interest rates may have to go deeply negative, for example, -3% – 4%. First, they say “In summary, ten years after the crisis, it is clear that the zero-lower bound on interest rates has proved to be a serious obstacle for monetary policy. However, the zero lower bound is not a law of nature; it is a policy choice. We show that with readily available tools a central bank can enable deep negative rates whenever needed—thus maintaining the power of monetary policy in the future.” Next they declare “Our view is that, when needed, deep negative rates are likely to be worth the political cost. While the complete abolition of paper currency would indeed clear the way for deep negative interest rates whenever deep negative rates were called for, such proposals remain difficult to implement since they involve a drastic change in the way people transact.”

- The Bill Is Connected to Negative Interest Rates. The connection is obvious in that in a negative interest rate environment households and businesses will be likely to withdraw funds from the banking system and transact in cash. If enough cash is extracted, negative interest rates will simply have no effect. We believe the measures proposed in the current Bill are truly about enabling negative rates, yet this is not mentioned within the Bill. This is misleading and deceptive. The true motivations should be on the record. But it explains the short time frames.

- Households and Businesses Would Be Trapped In The Banking System. If such a ban was introduced households and businesses would be forced to use the banking system, meaning that bank charges could not be avoided, which benefits banks, not their customers. In addition, we have seen recent system and power failures which have caused disruption to the electronic payments systems. If cash is less available and restricted, a failure would be even more significant and inconvenient and could damage the economy. Once in the banking system, funds can be monitored and controlled (seen by the Taskforce as a positive move – we disagree), but such control could limit access to cash and transactions in general in a crisis. And we note from our SME surveys that many businesses, especially in rural and regional Australia regularly use cash as electronic alternatives are not available. Finally, offering cash for a discount, which is part of legitimate everyday business (because bank charges are avoided) would be removed.

- The Structure Allows Change by Regulation Subsequently. The structure of the Bill enables parameters to be changed subsequently by regulation (not via Parliament). This opens the door to removing some of the concessions contained in the current drafting by agencies without full scrutiny. The bill is therefore open ended with regards to crypto, precious metals and other carveouts. In addition, we note surprisingly, government transactions, and cash transactions in Casinos are carved out, which again flags concerns about the structure and limitations of the bill.

- A Reduced Limit Could Be Waived Through. Whilst we note that the $10,000 limit would require Parliamentary approval, in practice this could be made without full debate – as illustrated by the passage on the recent APRA bill, or as part of an omnibus “procedural” bill which masks the true intent. It is important to note that where cash transaction bans have been introduced, the value ceiling has been lowered. France has legally prohibited cash transactions above 1,000 euros, Spain has legally prohibited cash transactions above 2,500 euros, Italy has legally prohibited cash transactions above 3,000 euros, and the European Central Bank ended the production and issuance of its 500 euro note at the end of 2018.

In summary, my overriding concern is that Parliamentarians will only consider the narrow tax efficiency aspect of the Bill and vote it through without grasping the true intent and consequences. Civil liberties are being eroded, and the trap will be set to force households and businesses to transact within the banking system, thus facilitating experimental monetary policies, via the back door.

This Bill should not be allowed to pass.

[1] https://www.digitalfinanceanalytics.com/

[3] https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/162914

[4] https://voxeu.org/article/what-else-can-central-banks-do

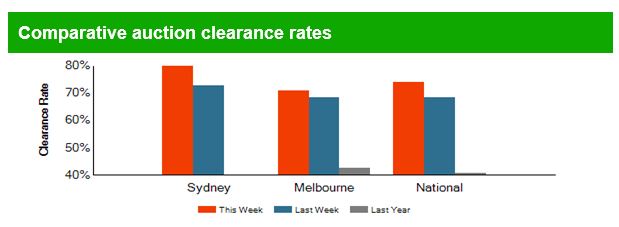

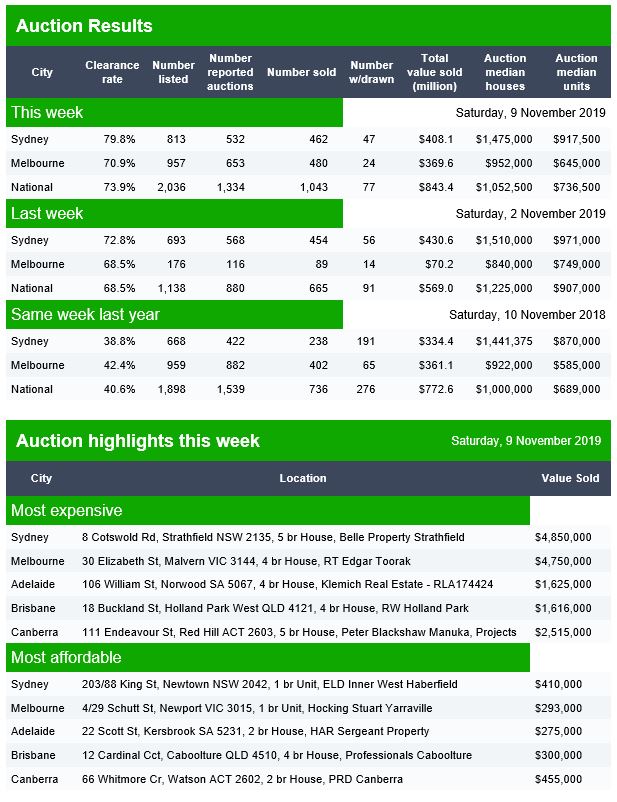

Auction Results 09 Nov 2019

Domain released their preliminary results for today.

Back to full bore this week, after the holidays in Melbourne last weekend, and a higher listing number than a year back (when the markets were fading fast).

Canberra listed 81 auctions, reported 60 and sold 42, with 2 withdrawn and 18 passed in, giving a Domain result of 68%. DFA listed to sold = 51.9%

Brisbane listed 112 auctions, reported 51 with 34 sold, 2 withdrawn and 17 passed in giving a Domain result of 64%. DFA listed to sold = 34%

Adelaide listed 73 and reported 39 with 26 sold, 2 withdrawn and 13 passed in, giving a Domain result of 63%. DFA listed to sold = 35.6%

The Roller Coaster Ride Continues – The Property Imperative Weekly 09 Nov 2019

The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Contents:

00:24 Introduction

1:23 US China Trade Talks

3:04 US Markets

6:15 China

7:50 Australian Section

7:55 RBA on Monetary Policy

10:50 Household Confidence

11:10 Lending

11:40 REA

14:50 High Rise Construction

15:30 Property Market

16:20 Auctions

16:50 Bank Profit Results

17:50 Australian Markets