The Committee on the Global Financial System at The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has published an important report “Structural changes in banking after the crisis“.

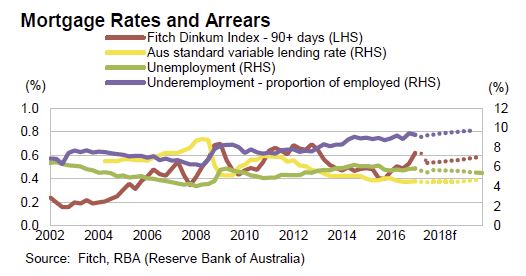

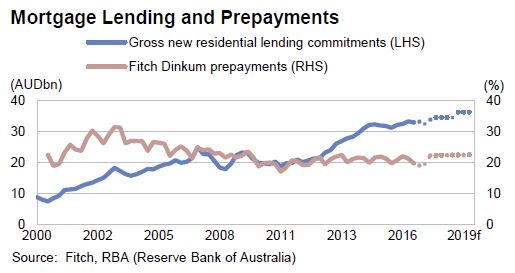

The report highlights a “new normal” world of lower bank profitability, and warns that banks may be tempted to take more risks, and leverage harder in an attempt to bolster profitability. This however, should be resisted. They also underscore the issues of banking concentration and the asset growth, two issues which are highly relevant to Australia.

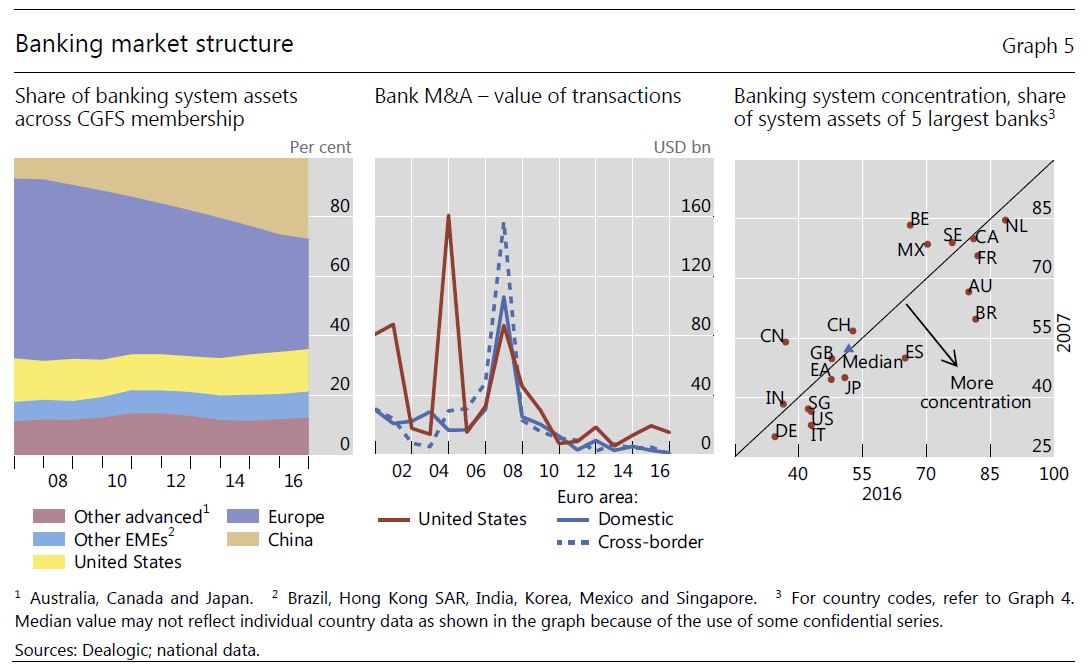

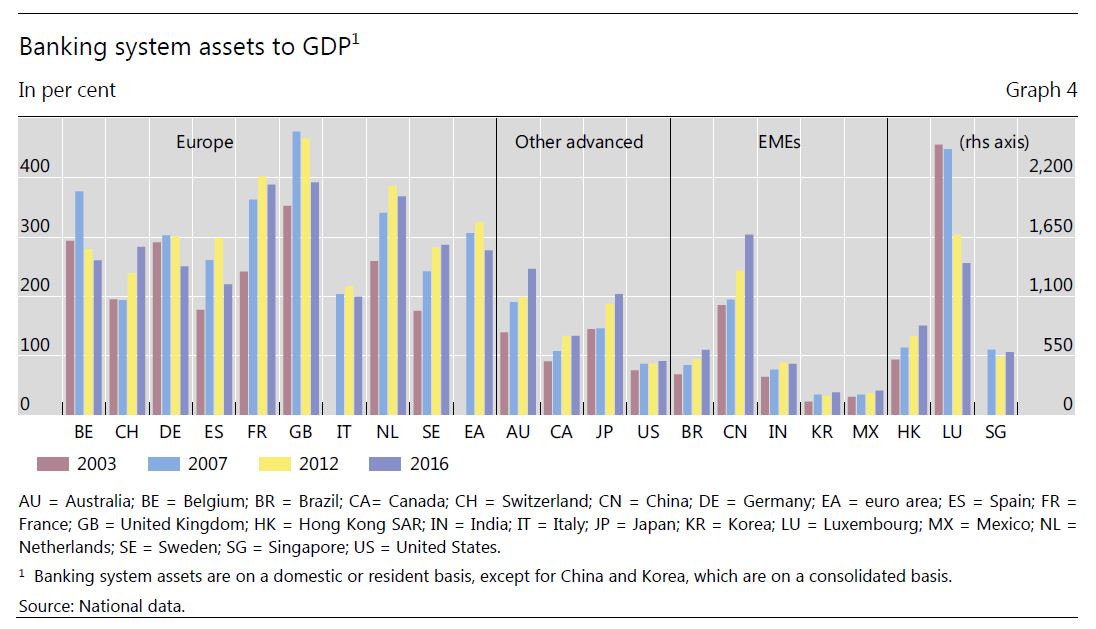

The report highlights that in some countries the 2007 banking crisis brought about the end of a period of fast and excessive growth in domestic banking sectors. Worth noting the substantial growth in Australia, relative to some other markets and of particular note has been the dramatic expansion of the Chinese banking system, which grew from about 230% to 310% of GDP over 2010–16 to become the largest in the world, accounting for 27% of aggregate bank assets.

They also call out the concentration banking to a smaller number of larger players since the crisis. The number of banks has fallen in most countries

They also call out the concentration banking to a smaller number of larger players since the crisis. The number of banks has fallen in most countries

over the past decade. Post-crisis reductions in bank numbers have been mainly among smaller institutions, aside from a handful of distressed large banks in the euro area and the retreat of some international banks from specific foreign markets. Concentration has also risen in some countries that were less affected by the crisis and where bank numbers have

continued to expand or remained steady (Australia, Brazil, Singapore).

The decade since the onset of the global financial crisis has brought about significant structural changes in the banking sector. The crisis revealed substantial weaknesses in the banking system and the prudential framework, leading to excessive lending and risk-taking unsupported by adequate capital and liquidity buffers. The effects of the crisis have weighed heavily on economic growth, financial stability and bank performance in many jurisdictions, although the headwinds have begun to subside. Technological change, increased non-bank competition and shifts in globalisation are still broader environmental challenges facing the banking system.

Regulators have responded to the crisis by reforming the global prudential framework and enhancing supervision. The key goals of these reforms have been to increase banks’ resilience through stronger capital and liquidity buffers, and reduce implicit public subsidies and the impact of bank failures on the economy and taxpayers through enhanced recovery and resolution regimes. At the same time, the dynamic adaptation of the system and the emergence of new risks warrant ongoing attention.

In adapting to their new operating landscape, banks have been re-assessing and adjusting their business strategies and models, including their balance sheet structure, cost base, scope of activities and geographic presence. Some changes have been substantial and are ongoing, while a number of advanced economy banking systems are also confronted with low profitability and legacy problems.

This report by the CGFS Working Group examines trends in bank business models, performance and market structure, and assesses their implications for the stability and efficiency of banking markets.

The main findings on the evolution of banking sectors are as follows:

- Changes in banking market capacity and structure. The crisis ended a period of strong growth in banking sector assets in many advanced economies. Several capacity metrics point to a shrinking of banking sectors relative to economic activity in several countries directly impacted by the crisis. This adjustment has occurred mainly through a reduction in business volumes rather than the exit of firms from the market. Banking sectors have expanded in countries that were less affected by the crisis, particularly the large emerging market economies (EMEs). Concentration in banking systems has tended to increase, with some exceptions.

- Shifts in bank business models. Advanced economy banks have tended to reorient their business away from trading and more complex activities, towards less capital-intensive activities, including commercial banking. This pattern is evident in the changes in banks’ asset portfolios, revenue mix and increased reliance on customer deposit funding. Large European and US banks have also become more selective and focused in their international banking activities, while banks from the large EMEs and countries less affected by the crisis have expanded internationally.

- Trends in bank performance. Bank profitability (return on equity) has declined across countries and business model types from the historically high rates seen before the crisis. At least in part, this reflects lower leverage induced by the regulatory reforms. In addition, many advanced economy banks, in particular banks in some European countries, are facing sluggish revenues and an overall cost base that has been resistant to cuts, including, in some cases, legacy costs associated with past investment decisions and misconduct.

The main findings regarding the impact of post-crisis structural change for the stability of the banking sector are related to three areas:

- Bank resilience and risk-taking. Banks globally have enhanced their resilience to future risks by substantially building up capital and liquidity buffers. The increased use of stress testing by banks and supervisors since the crisis also provides for greater resilience on a forward-looking basis, which should help support credit flows in good and bad times. In addition, advanced economy banks have shifted to more stable funding sources and invested in safer and less complex assets. Some of these adjustments may be driven partly by cyclical factors, such as accommodative monetary policy, and hence may diminish as conditions change. Qualitative evidence

indicates that banks have considerably strengthened their risk management and internal control practices. Although these changes are hard to assess, supervisors point to significant scope for further improvements, in particular because of the inherent uncertainties about the future evolution of risks. - Market sentiment and future bank profitability. Despite a recovery in marketbased indicators of investor sentiment towards larger institutions in recent years, equity investors remain sceptical towards some banks with low profitability. Simulation analysis carried out by the Working Group suggests that some institutions need to implement further cost-cutting and structural adjustments.

- System-wide effects. Assessing the impact of structural change on system-wide stability is harder than in the case of individual banks because of complex interactions within the system. Nonetheless, a number of changes are consistent with the objectives of public authorities and the reform process. First, banks appear to have become more focused geographically in their international strategy and tend to intermediate more of their international claims locally. Second, direct connections between banks through lending and derivatives exposures have declined. Third, some

European banking systems with relatively high capacity have made progress with consolidation. Fourth, while the effect of less business model diversity arising from the repositioning of many banks towards commercial banking cannot be assessed yet, this trend has been accompanied by a shift towards more stable funding sources (such as deposits). A range of other reforms has also enhanced systemic stability (eg money market mutual fund reforms) and further progress has been made on resolution and recovery frameworks.

Changes in banking sector resilience have to be measured against the impact on the services provided by the sector. The main findings regarding the impact of changes on the efficiency of financial intermediation services are:

- Provision of bank lending to the real economy. Trends in bank-intermediated credit have been uneven over time and across countries, reflecting differences in their crisis experience and related overhang of credit. Credit declined significantly relative to economic activity in advanced economies that bore the brunt of the crisis, and in most countries started to recover only from 2015. But the adjustment is still ongoing

in others, reflecting in part a legacy of problem bank assets that continues to hamper the growth of fresh loans. By comparison, advanced economy banking systems not significantly affected by the crisis continued to report solid loan growth, notwithstanding tighter regulations.Recognising the difficulty of disentangling demand and supply drivers, the

evidence gathered by the group does not suggest a systematic change in the

willingness of banks to lend. But, in line with the objectives of regulatory reform, lenders have become more risk-sensitive and more discriminating across borrowers. In contrast to many advanced economies, bank lending has expanded strongly in EMEs, raising sustainability concerns and prompting the use of macroprudential measures and the tightening of certain lending standards more recently. - Capital market activities. Crisis-era losses combined with regulatory changes have motivated a significant reduction in risk and scale in the non-equity trading and market-making businesses of a number of global banks.

- International banking was one of the areas most affected by the crisis. Aggregate foreign bank claims have seen a significant decline since the crisis, driven particularly by banks from the advanced economies most affected by the crisis, especially from some European countries. By contrast, banks from other non-crisis countries have expanded their foreign activities, in some cases quite substantially, resulting in a significant change in the country composition of global banking assets.

The report highlights four key messages for markets and policymakers:

- Post-crisis, a stronger banking sector has resumed the supply of

intermediation services to the real economy, albeit with some changes in

the balance of activities.

– Bank credit growth remains below its excessive pre-crisis pace in advanced economies but without indications of a systematic reduction in the supply of local credit. Lending to some sectors and borrowers has seen reductions, however, as banks have adjusted their risk profile, and policymakers should remain attentive to potential unintended gaps in the flow of credit.

– Experience from crisis countries underscores the benefits of acting early in addressing problems associated with non-performing loans (NPLs).

– The withdrawal of some banks from capital markets-related business has

coincided with signs of fragile liquidity in some markets, although causality

remains an open question. - Longer-term profitability challenges require the attention of banks and

supervisors, as they may signal risk-taking incentives and overcapacity. Low profitability partly reflects cyclical factors but also higher capitalisation and more resilient bank balance sheets. As such, banks and their investors need to adapt to a “new normal”. Market concerns about low profitability may deprive banks of an important source of fresh capital, or encourage risk-taking and leverage by banks, thus placing a premium on robust risk management, regulation and supervision. In some cases, low profitability might also signal the existence of excess capacity and structural impediments to exit for individual banks, requiring decisive policy action to apply relevant rules. - Consolidation and preservation of gains in bank resilience requires ongoing

surveillance, risk management and a systemic perspective. Key indicators

show areas of improvement since the crisis, but also areas which are still a work in progress. Authorities and market participants should not become complacent. The system is adapting to a variety of changes, the interaction of which is difficult to predict. Authorities should monitor the ongoing adaptation and evolution in the nature and locus of risk-taking within the banking sector and the financial system more broadly. In this regard, the group sees scope for the international supervisory community to undertake a post-crisis study of bank risk management practices. In addition, ample buffers remain critical to coping with unexpected losses from new risks. - Better use and sharing of data are critical to enhanced surveillance of

systemic risk. Surveillance is crucial, given that the financial sector evolves

dynamically and because future risks will likely differ from past ones. Although data availability has improved, there is a need to make better use of existing data to assess banking sector structural adjustment and related risks. This effort will likely require additional conceptual work, building on the data sets of national authorities and the international financial institutions. Areas that warrant further analysis include the potential for increased similarities in the exposure profile of banks to correlated shocks, the growing role and implications of fintech, and the migration of activity and risk to the non-bank sector.