Home prices are more to do with sentiment that fundamental economics, and this week we saw new data, so are home prices on their way down?

Welcome to the Property Imperative weekly to the 25 November 2017. Watch the video, or read the transcript.

Welcome to the Property Imperative weekly to the 25 November 2017. Watch the video, or read the transcript.

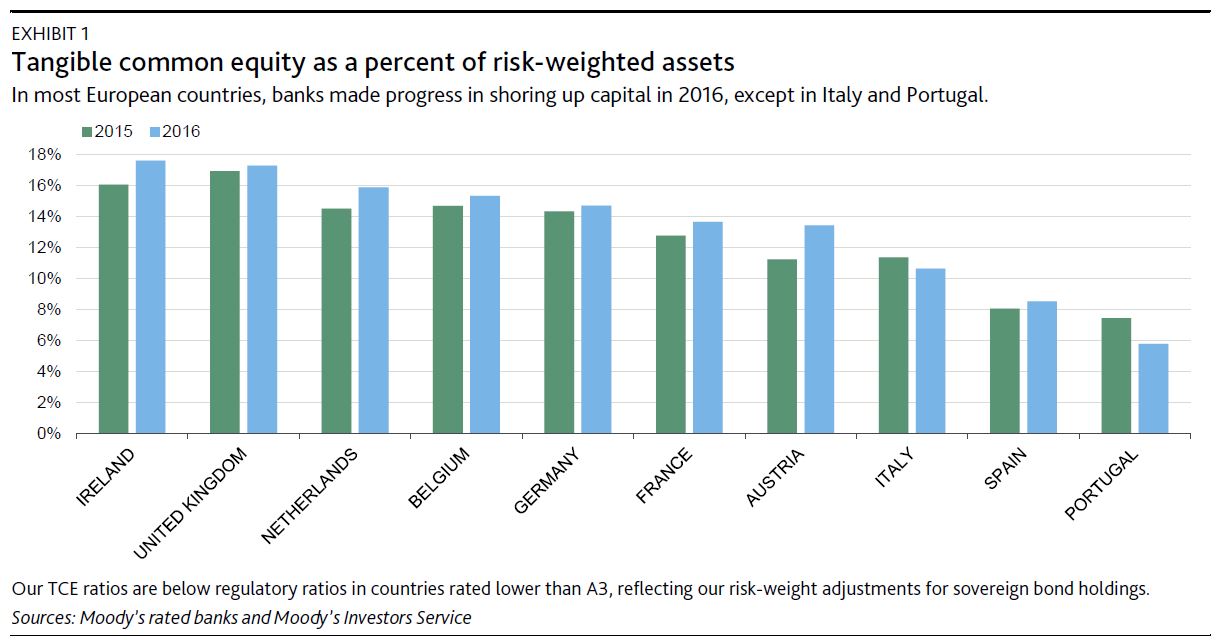

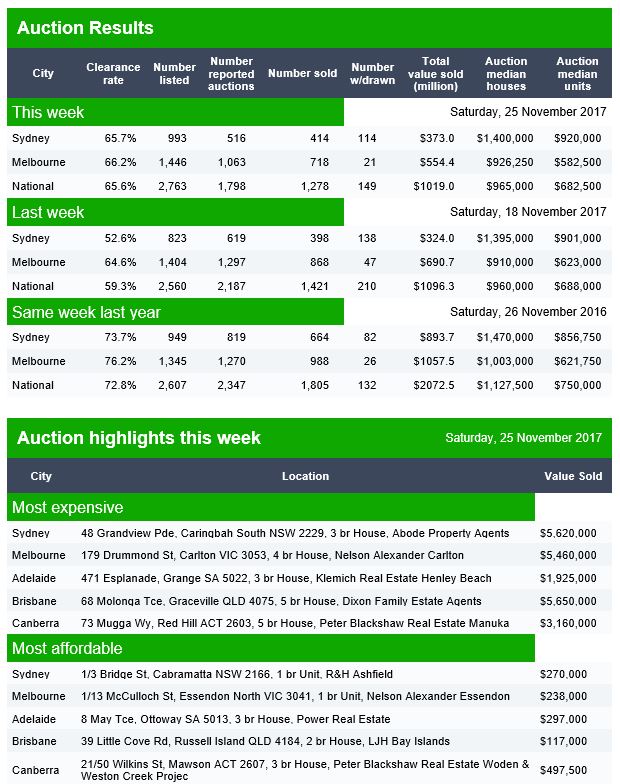

We start this week’s digest of finance and property news noting that Auction clearance rates continue to drift lower, especially in Sydney and home prices are easing back as the supply/demand equation changes.

CommSec said the average floor size of an Australian home (houses and apartments) has fallen to a 20-year low, with the typical new home now 189.8 square metres, down 2.7 per cent over the past year and the smallest since 1997. Though Australians continue to build some of the biggest houses in the world, an increasing proportion of Australians – especially in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane – also want smaller homes like apartments, semi-detached homes and town houses. Generation Y, Millennials, couples and small families want to live closer to work, cafes, restaurants, shopping and airports and are giving up living space for better proximity to the desirable amenities. CBA also make the point that since 2014 the number of people per dwelling has been falling. Lower interest rates and the increased supply of cheaper apartments (compared with houses) have prompted older couples to down-size. More Generation Y have been looking to move out of home and take ownership of accommodation more appropriate to their needs.

Also on the supply/demand property equation was an important study from the ANU. The Government view is high home prices is ultimately driven by lack of supply, relative to demand, including from migration. So the solution is to build more (flick pass to the States!). It has nothing to do with excessive debt, nor does the fact the average number of people per home is falling signify anything. And tax policy is not the problem. But the working paper “Regional housing supply and demand in Australia” from the ANU Center for Social Research and Methods, blows a mighty hole in that mantra. They suggest that demand factors (availability of loans, tax concessions etc.) have a significant impact, while demand and supply equilibrium varies significantly across different regions, with some hot spots, and some where vacant property exists (yet prices remain high, because of these demand factors). Significantly, much of the surplus is in areas where high-rise development has been strong. We think this may signal further downward pressure on prices in areas like Central Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane as well as Townsville and Cairns. On the other hand, there is a shortage of property in Adelaide, and some outer suburban areas.

Wayne Byers, APRA Chairman spoke at the Australian Securitisation Forum 2017. Household debt is high, and continues to rise he said. He identified three mortgage related risks. First, the trend in non-performing housing loans is upward, despite a relatively benign environment for lenders. In fact the overall rate of non-performing housing loans is drifting up towards post-crisis highs, without any sign of crisis and when rates are ultra low.

Second, while the upward trend in low Net Income Surplus (NIS) lending appears to have moderated over the past few quarters, a reasonable proportion of new borrowers have limited surplus funds each month to cover unanticipated expenses, or put aside as savings.

Third, there is only a slight moderation in the proportion of borrowers being granted loans that represent more than six times their income. As a rule of thumb, an LTI of six times will require a borrower to commit 50 per cent of their net income to repayments if interest rates returned to their long term average of a little more than 7 per cent. High LTI lending in Australia is well north of what has been permitted in other jurisdictions grappling with high house prices and low interest rates, such as the UK and Ireland.

So, APRA finally acknowledge there are risks in the system and is finally looking at LTI. Better late than never…! LVR is not enough. He also called on the finance industry to “devote more effort to the collection of realistic living expense estimates from borrowers” and give “greater thought” to the appropriate use and construct of benchmarks”.

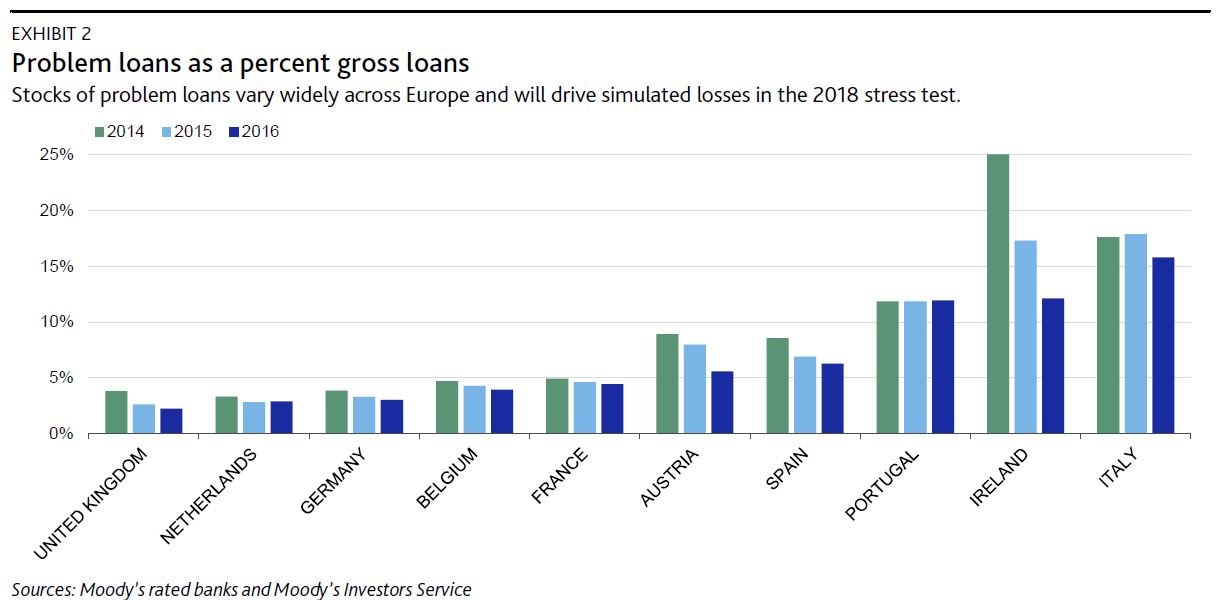

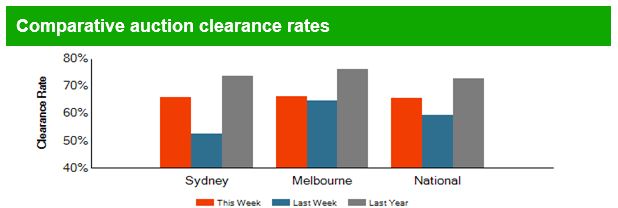

So how big is the problem? Well, the long data series from the Bank for International Settlements comparing household debt to GDP shows that Australia sits at the top of the international list after Switzerland at 122%. Australian households are wallowing in debt (no wonder mortgage stress is so high), even relative to Canada (where home prices have now started to fall), Hong Kong (where prices are in absolute terms higher), and New Zealand (where the Reserve Bank there has been much more proactive in tacking the ballooning debt). Ireland is still trying to deal with the collapse which followed the GFC in 2007 and they have registered a significant plunge in debt.

Another BIS series, trends in home prices, updated this week, shows Australia is near the top in terms of growth, relative to other western countries, including UK, USA, Canada and New Zealand. There is an important lesson in this data. If prices do crash it can take significant time to recover. Home prices in Ireland, which peaked in 2007, 10 years later are still well below the peak – a salutatory warning. USA prices have now just passed their pre-GFC peak and the UK achieved this in 2014! The fallout from home price falls cast a long shadow. The fall in prices took on average 5 years from their peak to the subsequent trough. A warning that if Australian prices slide, they could do so for many years.

The IMF issued a warning this week, based on their latest Australian visit. They warn that growth will be modest, more effort is required to contain housing risks – including macroprudential, and a structural reform agenda is required to lift productivity and growth. They say near-term risks to growth have become more balanced, but large external shocks, including their interaction with the domestic housing market, are an important downside risk. The housing market is expected to cool, but imbalances—lower housing affordability and household debt vulnerabilities—are unlikely to be corrected soon. Declines in household debt-to-income ratios would need to be driven by strong nominal income growth and amortization. They are however, stuck on the supply-side policy mantra as the most effective approach to achieving housing affordability in the longer term.

The RBA had a good trot this week, with Head of Financial Stability Jonathan Kearns, saying the Bank has responsibility to promote the stability of the financial system as a whole so carefully monitors property markets because poor commercial property lending and the large stock of residential property debt means risks to financial stability and household resilience. The high valuation of commercial property increases the potential for a sharp correction and so the risks from commercial property lending. The high level of household mortgage borrowing also brings risks, both for lenders and households. He also discussed the impact of purchases and financing by foreigner investors and banks. Nationally, purchases by foreign buyers are equivalent to around 10-15 per cent of new construction, or about 5 per cent of total housing sales. He said, these purchases by foreign buyers do not, on the whole, reduce the supply of dwellings available to local residents and in fact may actually contribute to expansion of the housing stock – though such purchases by foreign buyers, particularly for investment purposes, are a more recent phenomenon and so their impact on the housing cycle is less clear.

Marion Kohler, Head of Domestic Markets Department, RBA, explored more from their mortgage Securitisation Dataset. There were two insights. First the LVR distribution is highest at 80% (which is skewed because of the securitisation rules), but her claim “on average, securitised loans appear to be no riskier than the broader population of mortgages, was unproven. Second there was some interesting commentary on mortgage rates, with interest-only loans now significantly higher. There is now a greater proportion of principal-and-interest loans with an interest rate below 4 per cent, due to the lower rates applied to owner-occupier loans, and there has reportedly been increased competition for these types of loans. She did not discuss the critical Loan to Income ratios, which should be available in the data!

Finally, RBA Governor Philip Lowe spoke at the Australian Business Economists Annual Dinner. Essentially, the conundrum of low inflation and wage growth, despite better employment means the cash rate will stay lower for longer, though the next move is likely up. High household debt is less about risks to the banking system and more about medium term financial stability, especially as rates rise. Household spending will remain muted. GDP is forecast to be higher because the fall in mining investment has ended, even if other business investment is still low. He also highlighted the bank keeps overestimating future consumption growth. Finally, he said that it is important to be clear that the RBA does not have a target for housing prices. But a return to more sustainable growth in housing prices does reduce the medium-term risks.

A report by Bloomberg says the party is finally winding down for Australia’s housing market. How severe the hangover is will determine the economy’s fate for years to come. After five years of surging prices, the market value of the nation’s homes has ballooned to A$7.3 trillion — or more than four times gross domestic product. Not even the U.S. and U.K. markets achieved such heights at their peaks a decade ago before prices spiralled lower and dragged their economies with them. The report cited UBS economists’ declaration that “Australia’s world-record housing boom is officially over, and the cooling may be happening a bit more quickly than even we expected.”

The risk is that it leaves the Australian economy extremely exposed, and a minor shock could become far more significant,” said Daniel Blake, an economist at Morgan Stanley in Sydney. While the RBA is satisfied that lenders have adequate buffers to cope with any downturn, banks may find it harder to value their collateral in a falling market as investors look to consolidate their portfolios of multiple homes.

Now reflect on this, more than half of all dividends in Australia come from the banks. Data from the latest Janus Henderson Global Dividend Index reveals that Australia’s banks pay $6 out of every $11 of the country’s dividends each year but dividends are growing slowly given already high payout ratios. Leading is Commonwealth Bank which raised its per share payout 3.7 per cent on the back of steady profit growth, but National Australia, Westpac and ANZ all held their dividends flat. CBA and Westpac were identified in the report as the world’s fourth and sixth biggest dividend payers respectively, with Chinese and Taiwanese technology and manufacturing companies taking the top three place. Much of the dividends in Australia comes from mortgage lending.

Standing back, home prices have been rising thanks to high local and foreign demand, and from investors who believe in yet higher prices ahead. But now the evidence is mounting that sentiment is changing, demand is easing (and as lending standards get tightened) and low wage growth in rising and living costs bite. Our household surveys picked this up a few weeks back, and now there is also more awareness of the risks from higher rates ahead.

So we think prices are set to slide further, with Sydney leading the way. Brisbane will follow, but there may be a little more momentum in Melbourne. All the economic data points in the same direction, and our modelling suggests a fall of 20% or more is possible, over the medium term. If we are lucky, the easing will be gentle, but could last for perhaps 5 years, but there is also a risk of a bigger fall sooner. This would create a negative feedback loop which would reduce growth and hit the banks hard. No wonder then many with vested interests in property still want to talk the market up, but the fundamentals don’t lie. It’s not now a question of if, but when, and how far home prices will fall.

That’s the Property Imperative weekly to 25 November 2017. If you found this useful, do leave a comment below, subscribe to receive future updates and check back again next week. Thanks for taking the time to watch. See you next time.