The Productivity Commission has released their draft report on the $2.6 trillion superannuation system. And they have done it again! A powerful ~500 pages of insight which cuts to the heart of the system. They raise some very imp0ortant points which shows the system is a lottery. They call for substantial reform. Five million member accounts are being shortchanged.

We see some similar patterns of behaviour to those revealed in the current Royal Commission. Not working for the best outcomes of members. Poor governance. Excessive fees. Poor disclosure and hidden charges and commissions. No wonder more households have chosen self managed super alternatives! They also question the current regulatory framework.

Performance varies thanks to fees

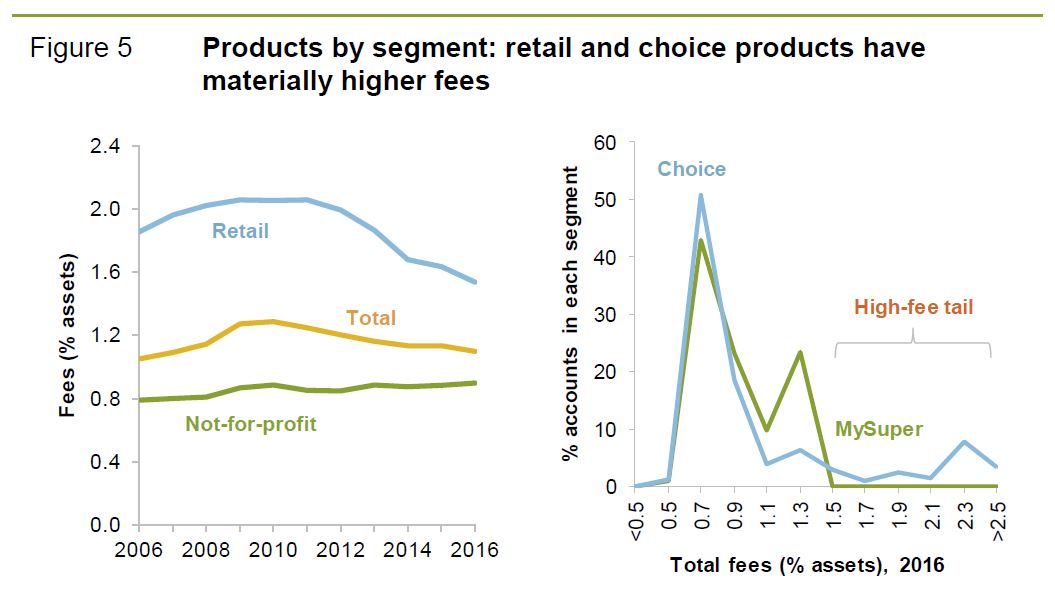

Embedded fees and multiple funds erode returns significantly, especially from “retail” funds. Australians pay over $30 billion a year in fees on their super (excluding insurance premiums).

Fees can have a substantial impact on members — for example, an increase in fees of just 0.5 per cent can cost a typical full-time worker about 12 per cent of their balance (or $100 000) by the time they reach retirement.

Fees can have a substantial impact on members — for example, an increase in fees of just 0.5 per cent can cost a typical full-time worker about 12 per cent of their balance (or $100 000) by the time they reach retirement.

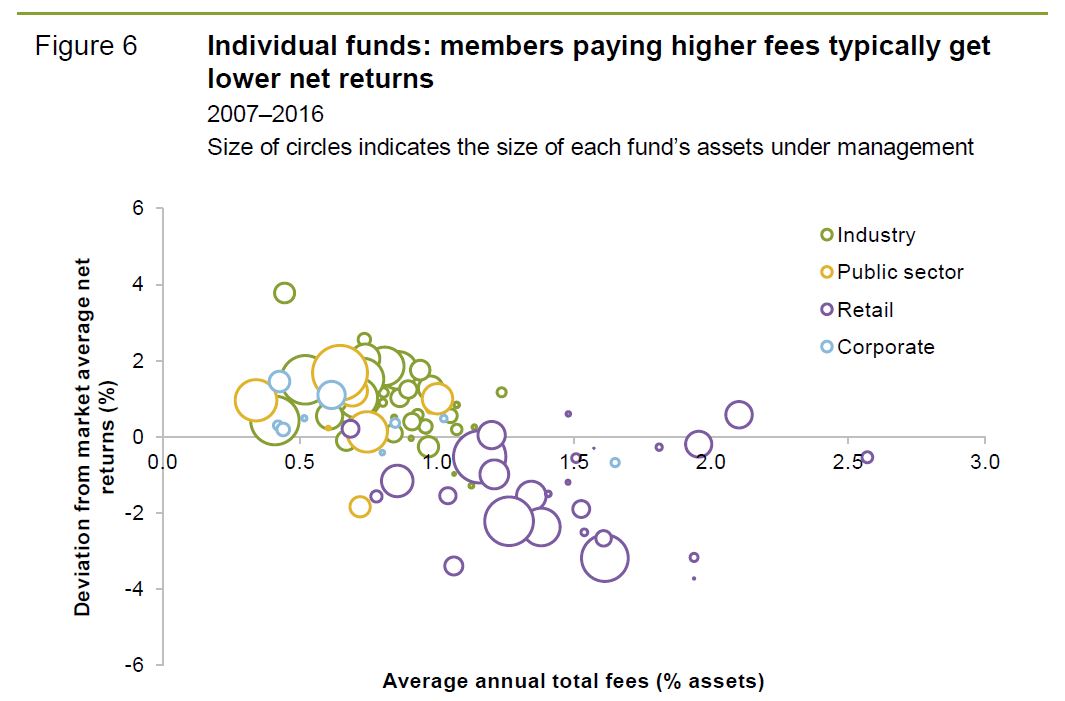

Fees charged by retail funds remain relatively high, at least for choice products. Roughly 14 per cent of member accounts appear to be paying annual fees in excess of 1.5 per cent of their balances. Fees can explain a

Fees charged by retail funds remain relatively high, at least for choice products. Roughly 14 per cent of member accounts appear to be paying annual fees in excess of 1.5 per cent of their balances. Fees can explain a

significant amount of the variation in net returns across super funds. Funds that charge higher fees tend to deliver lower returns, once both investment and administration fees have been netted off. Moreover, at least 2 per cent of accounts are still subject to trailing adviser commissions — despite such commissions being banned for new accounts by the Future of Financial Advice laws.

The Government says this highlights that some superfund operators have their snout firmly in the trough! Many of these reside within the big banks!

There is no shortage of regulation in the super system. Regulation is essential for a complex system holding large amounts of money and characterised by many disengaged members and potential conflicts of interest. But at times the regulators appear too focused on funds and their interests rather than on what members need.

Regulators need to focus more on member outcomes

The key regulators — APRA and ASIC — are doing well in their core duties of prudential regulation (APRA) and financial product and advice regulation (ASIC). There have been improvements over many years, and these will continue with recently proposed reforms to boost each regulator’s toolkit. Legislating an ‘outcomes test’ for MySuper products will give APRA greater scope to lift standards and remove authorisation from funds that are failing to act in the best interests of members (especially on mergers). And ASIC’s new product intervention powers will strengthen its ability to guard against upselling.

However, there is some confusion around the two regulators’ respective roles, given both have long held powers to police bad behaviour by trustee boards. For example, ASIC has traditionally been responsible for regulating conflicts of interest, but APRA has increasingly encroached on this role through its prudential standard setting. While much of APRA’s work is pre-emptive and out of public view, ASIC has traditionally been reactive (responding to misconduct only after the fact) and public. It has become increasingly unclear which regulator has primary responsibility for trustee conduct — with the risk of misconduct falling between the cracks and a lack of clear regulator accountability.

Strategic conduct regulation appears at times to be missing in action. Ideally, this would involve a regulator proactively identifying actual or potential instances of material member harm, investigating the underlying conduct and taking enforcement action in a way that provides a valuable public deterrent to future poor conduct. To date, there has been a deficit of public exposure of poor conduct (and associated penalties) to demonstrably discourage similar behaviour by others — now and in the future.

There are yawning gaps in data

A further area of weakness is how data on the system are collected. The regulators’ data collections are largely focused on funds and products, with a deficiency of member-based data. And there are major gaps and inconsistencies in the datasets held by regulators — such as the returns and fees experienced by members of individual choice products, funds’ outsourcing arrangements and details of the insurance members hold through super. Our funds survey was designed to plug some of these gaps, but — as noted above — many responses fell well short of ‘best endeavours’, which of itself proved revealing .

Regulators have done much to improve the breadth and depth of their data holdings in recent years, but this has been off a low base. Major differences in definitions persist across regulators, and poor quality disclosure by funds appears to go unpunished. Progress has been slow in some areas because of industry opposition (largely on the basis of short-term compliance costs) and the lack of a strong member voice to give impetus to change.

The result is poor transparency, which leaves members in the dark as to what they are really paying for and makes it harder for engaged members to compare products and identify the best performing funds. This suppresses competitive pressure on the demand side, and gives rise to the perverse risk of worse outcomes for members who do get engaged. The lack of transparency also makes it hard for regulators to effectively monitor the system and to hold funds to account for the outcomes they

The draft report makes the following key points:

- Australia’s super system needs to adapt to better meet the needs of a modern workforce and a growing pool of retirees. Currently, structural flaws — unintended multiple accounts and entrenched underperformers — harm a significant number of members, and regressively so. Fixing these twin problems could benefit members to the tune of $3.9 billion each year. Even a 55 year old today could gain $61 000 by retirement, and lift the balance for a new job entrant today by $407 000 when they retire in 2064.

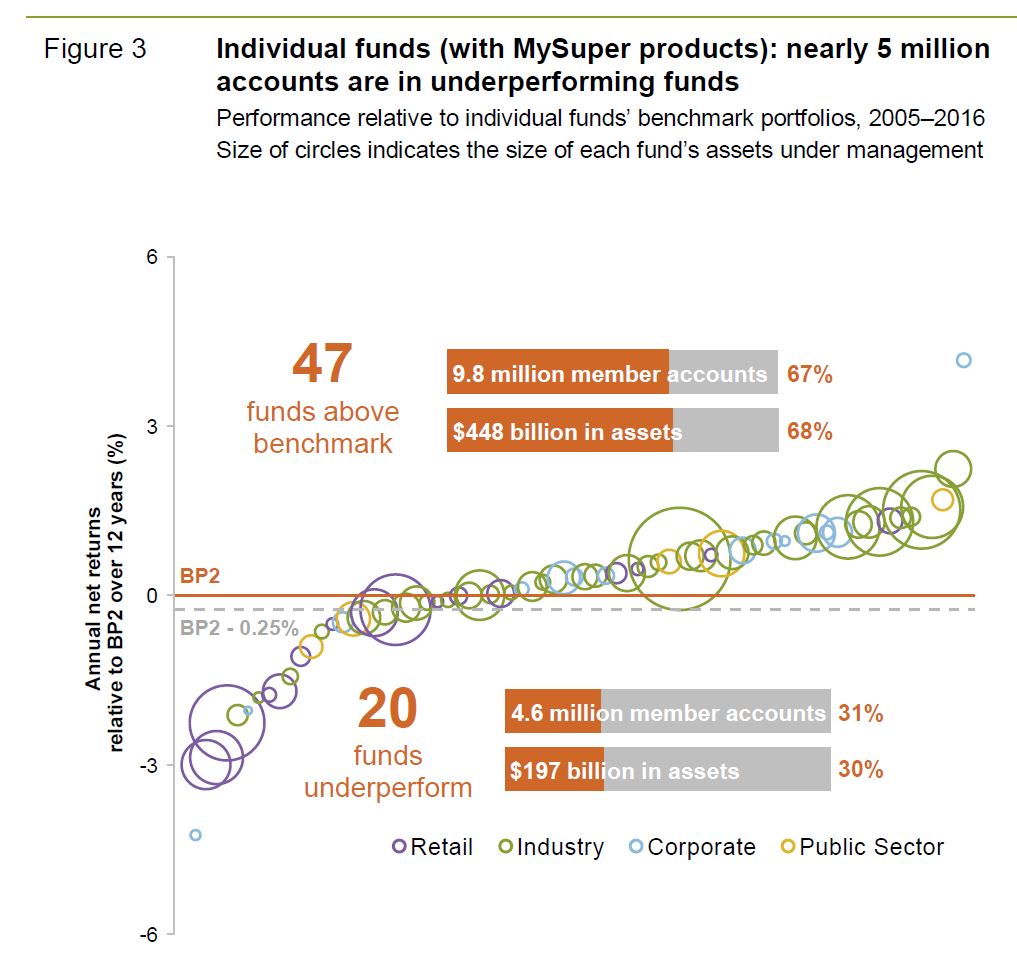

- Our unique assessment of the super system reveals mixed performance. While some funds consistently achieve high net returns, a significant number of products (including some defaults) underperform markedly, even after adjusting for differences in investment strategy. Most (but not all) underperforming products are in the retail segment. Fees remain a significant drain on net returns. Reported fees have trended down on average, driven mainly by administration costs in retail funds falling from a high base. A third of accounts (about 10 million) are unintended multiple accounts. These erode members’ balances by $2.6 billion a year in unnecessary fees and insurance.The system offers products and services that meet most members’ needs, but members lack access to quality, comparable information to help them find the best products. Not all members get value out of insurance in super. Many see their retirement balances eroded — often by over $50 000 — by duplicate or unsuitable (even ‘zombie’) policies.

- Inadequate competition, governance and regulation have led to these outcomes. Rivalry between funds in the default segment is superficial, and there are signs of unhealthy competition in the choice segment (including the proliferation of over 40 000 products). The default segment outperforms the system on average, but the way members are allocated to default products leaves some exposed to the costly risk of being defaulted into an underperforming fund (eroding over 36 per cent of their super balance by retirement). Regulations (and regulators) focus too much on funds rather than members. Subpar data and disclosure inhibit accountability to members and regulators.

- Policy initiatives have chipped away at some of the problems, but more changes are needed.

- A new way of allocating default members to products should make default the exemplar.Members should only ever be allocated to a default product once, upon entering the workforce. They should also be empowered to choose their own super product by being provided a ‘best in show’ shortlist, set by a competitive and independent process.An elevated threshold for MySuper authorisation (including an enhanced outcomes test) would look after existing default members, and give those who want to get engaged products they can easily and safely choose from (and compare to others in the market). This is superior to other default models — it sidesteps employers and puts decision making back with members in a way that supports them with safer, simpler choice.

- These changes need to be implemented in parallel to other essential improvements. Stronger governance rules are needed, especially for board appointments and mergers. Funds need to do more to provide insurance that is valuable to members. The industry’s code of practice is a small first step, but must be strengthened and made enforceable. Regulators need to become member champions — confidently and effectively policing trustee conduct, and collecting and using more comprehensive and member-relevant data.

Written submissions can be made by Friday 13 July 2018.