From The Conversation.

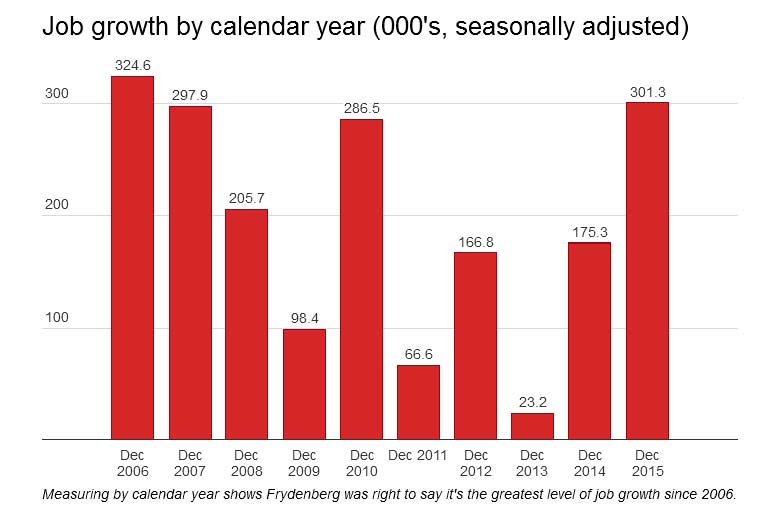

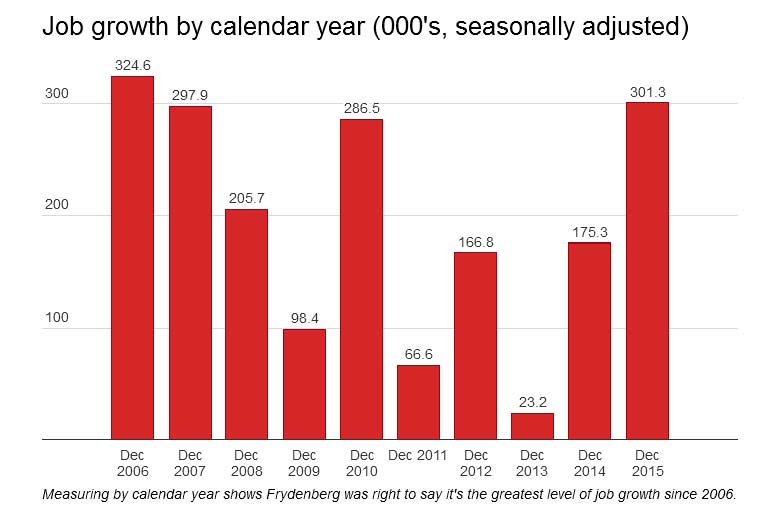

If you look at the latest unemployment numbers down to 5.8%, we have seen extremely strong job growth, over 300,000 jobs in the last year and that’s the greatest level of job growth since 2006. So I am very confident in the strength of our economy overall. – Josh Frydenberg, Minister for Resources, Energy and Northern Australia, interview with Fran Kelly on Radio National Breakfast, January 18, 2016.

With shakes in the global stock market and uncertainty abroad, politicians are understandably keen to reassure voters that Australia’s economic fundamentals are strong.

Employment data produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is one way we can test Australia’s economic waters, and resources and energy minister Josh Frydenberg said recently that the latest employment figures show extremely strong job growth.

Is he right?

Checking the numbers

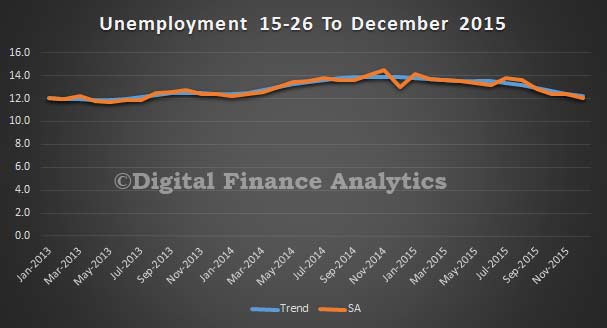

The ABS’ December Labour Force survey release showed that over the course of 2015, total employment was up by 301,300 people (adjusted for regular seasonal fluctuations and rounded to closest 100 people). Of those 301,300 jobs, the majority (187,200) were full time.

In the last three months of 2015, growth compared to same time the previous year has fluctuated between 2.6% and 3%. That’s above the average annual growth in employment since 2000 of around 1.9%. In short, employment growth recently has been strong.

Is it the greatest level of job growth since 2006?

Table 1 of the release shows that this growth is indeed the strongest of any calendar year since 2006.

However, one could also look at changes over the 12 months to any month. Doing that, you could say, for example, that November 2010 with a figure of around 314,300 had a stronger level of job growth than the latest employment figure show. It was also stronger in November of 2015, when it was at about 344,900.

However, one could also look at changes over the 12 months to any month. Doing that, you could say, for example, that November 2010 with a figure of around 314,300 had a stronger level of job growth than the latest employment figure show. It was also stronger in November of 2015, when it was at about 344,900.

In other words, if you look only at changes for calendar years (between the beginning and the end of any given year), Frydenberg is right to say it’s the greatest level of job growth since 2006.

That said, comparing the recent data to particular points in the past is less important than what the data tell us about the current trends in the labour market.

Trends

While the ABS devotes considerable resources to undertaking the survey, it is worth remembering that published employment growth is an estimate. The survey is only a sample of the population. The ABS reports on page 40 of its release that the standard error of monthly employment growth is 29,300 people, so, while employment growth recently has been strong, considerable uncertainty surrounds the numbers.

More generally, monthly movements in these data are volatile. For example, in December employment actually fell marginally, although this followed two months of strong growth and therefore was still a good outcome.

Due to this volatility in the monthly series, the ABS’ trend series may provide a better guide about the extent to which recent growth is likely to persist in the future.

Over the last three months of 2015, growth in trend employment averaged around 30,300 people, compared to 43,000 based on the data adjusted only for regular seasonal fluctuations.

In other words, the data show us that the underlying trends in the job market recently have been pretty good.

Other, unofficial, data point to an improvement in the labour market. The December 2015 ANZ Job Advertisement Index showed growth compared to the same time in 2014 in their trend estimate at 11.4%, compared to around 10% in the middle of 2015.

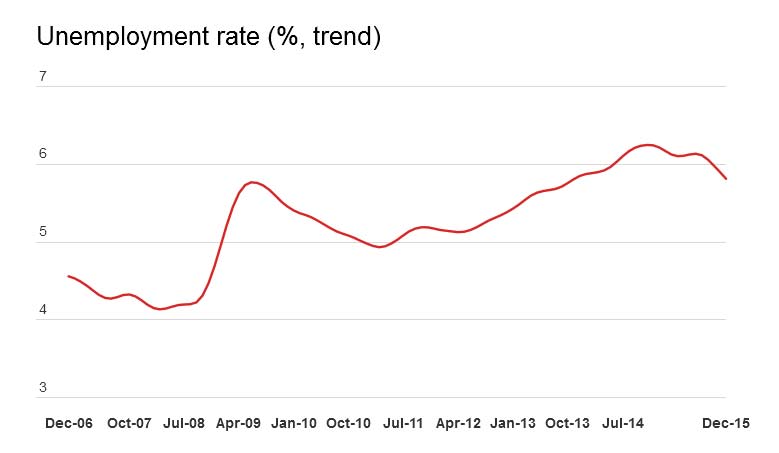

The unemployment rate

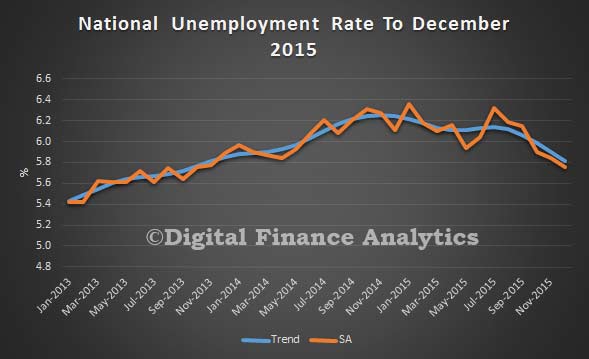

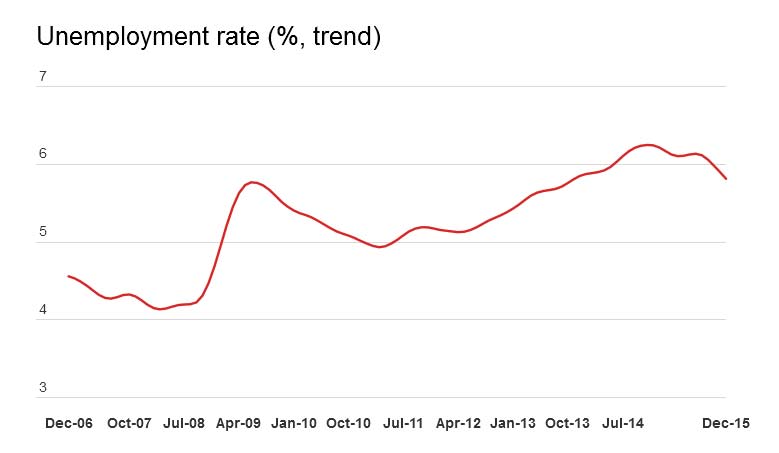

The unemployment rate, which is also produced by the ABS in the labour force survey, has improved over the last three months. At 5.8%, it is down from 6.2%, where it had fluctuated around since mid 2014 (see Table 1 of the release). Similarly, the trend unemployment rate has also improved and in December reached 5.8%.

Is 5.8% a good outcome for the unemployment rate? A simple benchmark is that average unemployment in Australia since 2000 is 5.5% – so it’s still currently a little above average.

Is 5.8% a good outcome for the unemployment rate? A simple benchmark is that average unemployment in Australia since 2000 is 5.5% – so it’s still currently a little above average.

Another way to judge the level of the unemployment rate is to look at developments in wages. If the unemployment rate was too low, growth in private sector wages would pick up. However, in the September quarter (which predates the recent drop in the unemployment rate) wages growth was soft.

To put Australian unemployment in a global context, the average unemployment rate of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations was 6.6% in November 2015. However, we need to caveat this comparison. Many countries, such as some in Europe, have unemployment rates that are, on average, higher than Australia’s, reflecting the different structure of their labour markets.

Australia’s unemployment rate has shifted down and that has persisted for three months, which gives greater confidence that it might not be temporary. However, given the volatility of these data and the uncertainty presently surrounding the outlook for the global economy it will be important to see whether these gains are maintained in coming months.

Verdict

Josh Frydenberg was right. Employment growth in 2015 was the strongest of any calendar year since 2006, although comparable growth also occurred over the 12 months to November 2010. It is also fair to say Australia has recently experienced strong jobs growth. – Tim Robinson

Review

This FactCheck is excellent in its comprehensive review and interpretation of the Labour Force Survey data. It is pointed out that labour market statistics, such as the unemployment rate and the number of people employed, are only estimates not the actual numbers in the population.

The statistics are based on the Labour Force Survey, which is a sample of 0.33% of the population about the employment status of everyone in the household aged 15 years and older. Because they are based on a sample of the population, the statistics have errors. In its monthly report the ABS publishes these “sampling errors” and clearly says that the estimate of the monthly change in the employment has a “95% confidence interval”. The media and the government rarely, if ever, report the range of estimates.

It is well known among economists that “you don’t trust one month’s figures” – the trend in labour force statistics is what’s important in understanding what’s going on in the labour market.

This FactCheck does a good job of explaining that the ABS “trend estimates” are much more reliable than the actual raw estimates. Again, the media (and politicians, when it suits them) tend to concentrate on the actual number, particularly whether it has risen or fallen. As the author also pointed out, the start and end date of the change usually makes a difference to the estimate of the change.

As the above states, although the minister’s assertion can be questioned somewhat by adopting a different start and end date, the overall conclusion that jobs growth is reasonably strong is correct. – Phil Lewis

Author: Tim Robinson, Research Fellow, Melbourne Institute, University of Melbourne; Reviewer: Phil Lewis, Professor of Economics, University of Canberra.

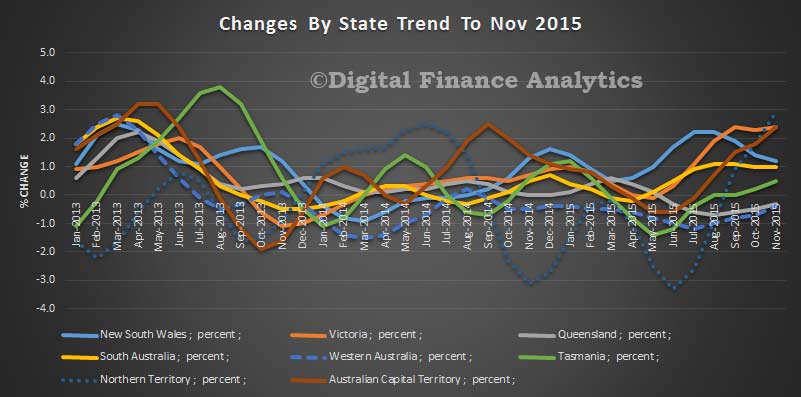

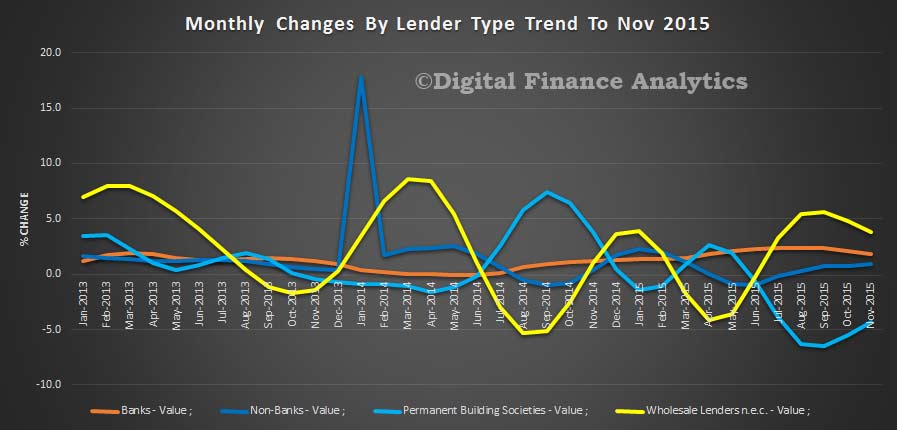

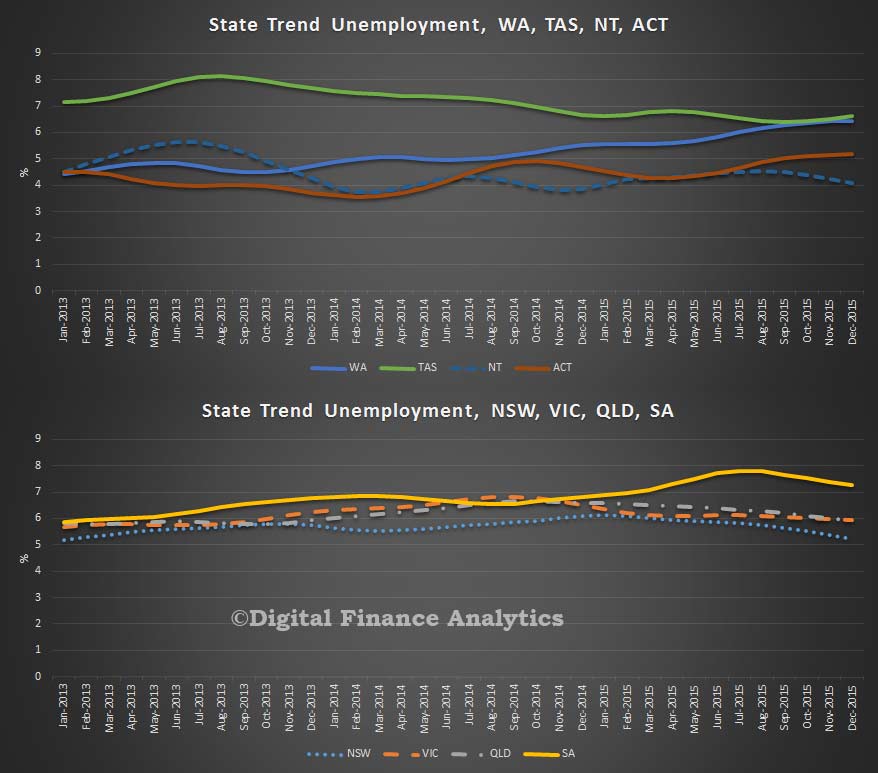

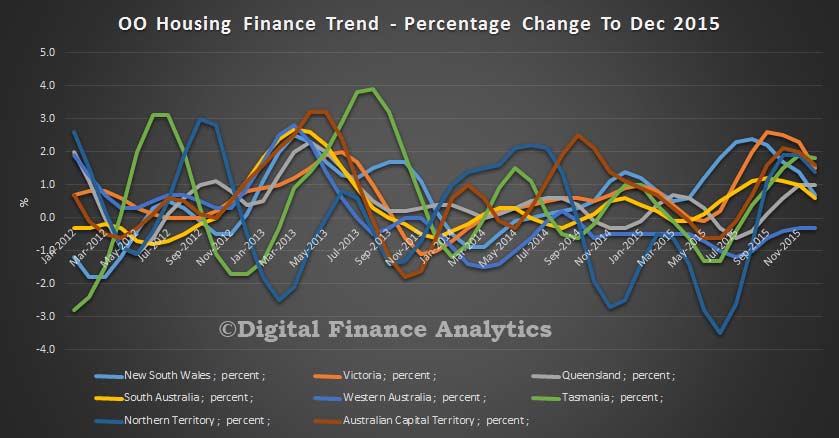

Looking at state trends, VIC led the way, up 1.5%, QLD at 1%, NSW at 0.7%, SA 0.6%, and WA down 0.3%. But startlingly, TAS reported a rise of 1.8% and NT a rise of 1.4%. The ACT was 1.6% higher. So, WA apart, owner occupied lending grew in every state.

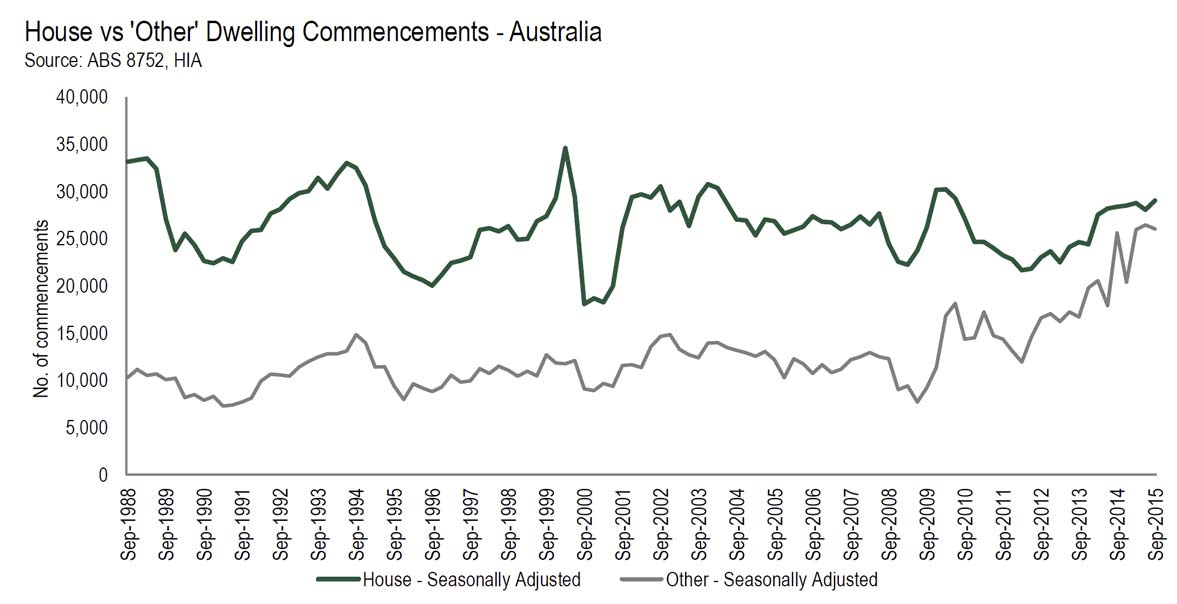

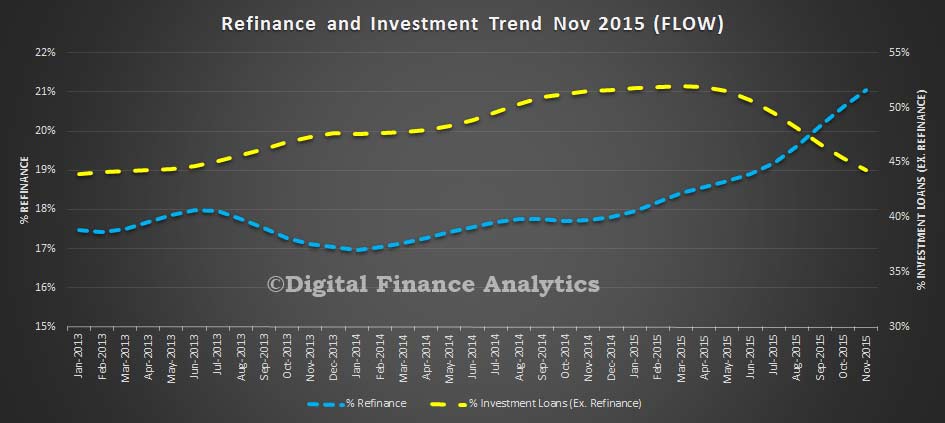

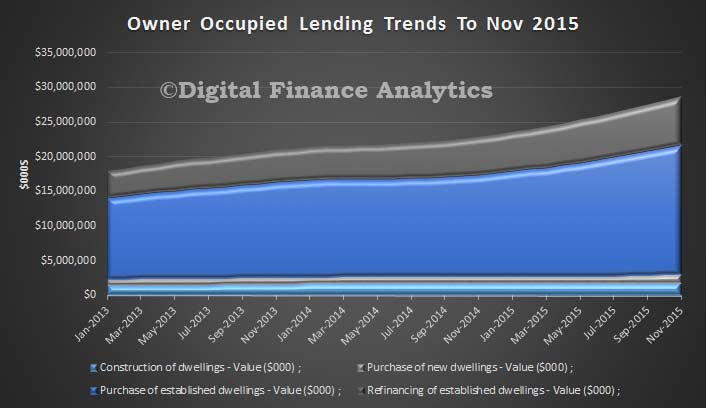

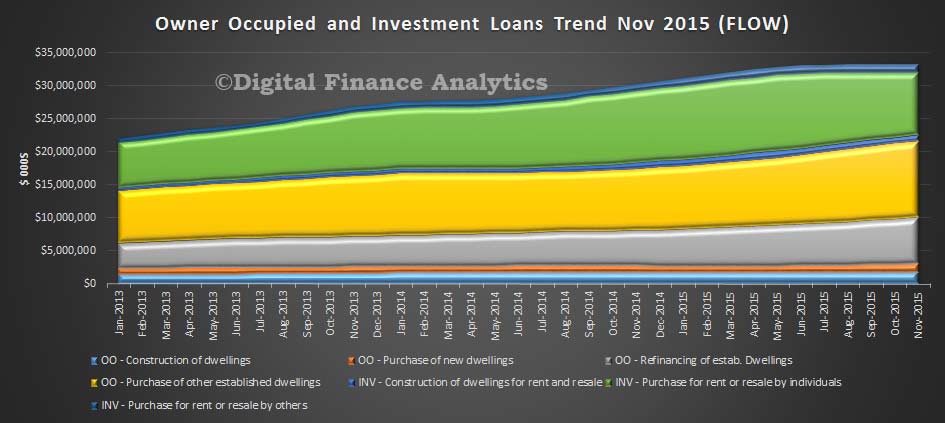

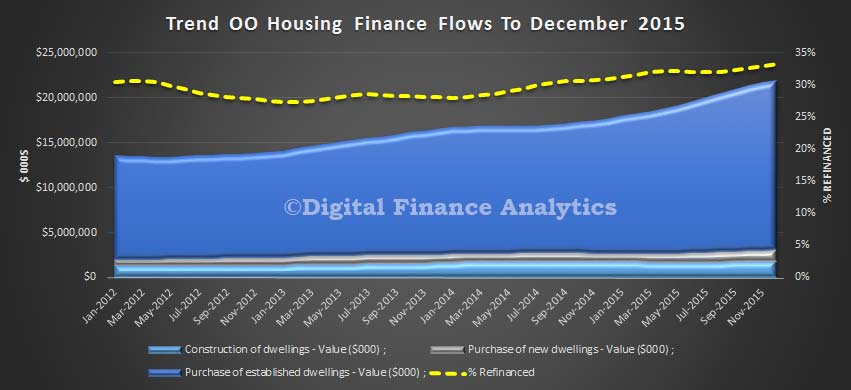

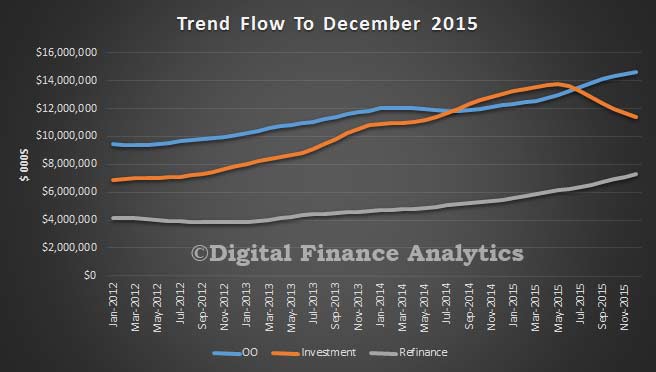

Looking at state trends, VIC led the way, up 1.5%, QLD at 1%, NSW at 0.7%, SA 0.6%, and WA down 0.3%. But startlingly, TAS reported a rise of 1.8% and NT a rise of 1.4%. The ACT was 1.6% higher. So, WA apart, owner occupied lending grew in every state. Total finance, including investment loans grew by just 0.025%, investment loans fell 2.36% to 11.4 bn. We see the clear focus of lending is to owner occupied borrowers, and a massive focus on churning loans. We also see a significant rise in the number of fixed rate deals, as households lock in low rates, with the number of deals up 17.2%, whilst secured revolving loans fell 9.8%. This reflects the cheap loan special offers which are currently in the market.

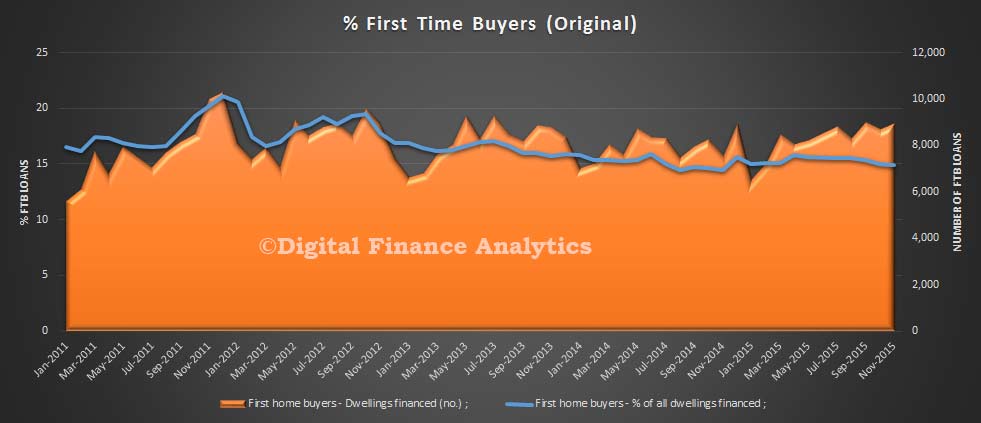

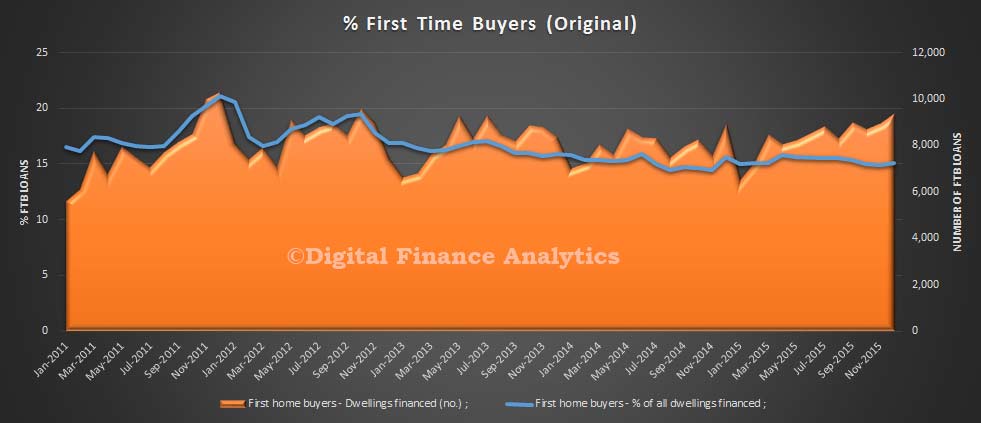

Total finance, including investment loans grew by just 0.025%, investment loans fell 2.36% to 11.4 bn. We see the clear focus of lending is to owner occupied borrowers, and a massive focus on churning loans. We also see a significant rise in the number of fixed rate deals, as households lock in low rates, with the number of deals up 17.2%, whilst secured revolving loans fell 9.8%. This reflects the cheap loan special offers which are currently in the market. First time buyer OO loans grew in December, with a rise of 4.6% on the previous month to make up 15.1% of new loans. This is faster than for non-first time buyer loans, here the number of loans grew 3.1%. The average loan size fell a little in the month, reflecting tighter lending criteria. This is original data, not trend smoothed.

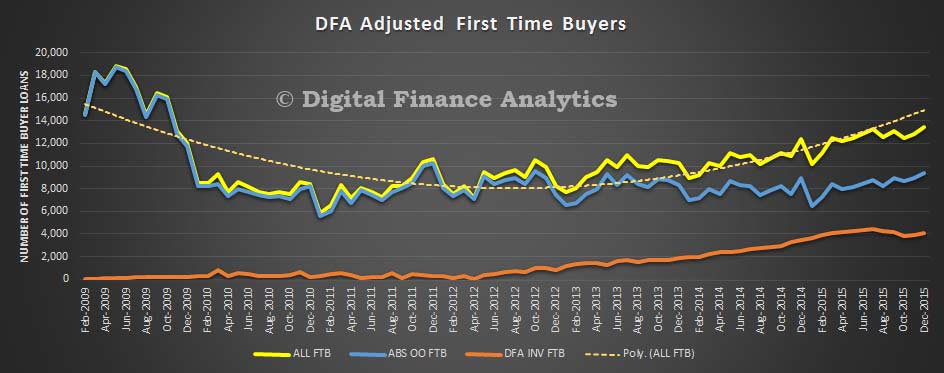

First time buyer OO loans grew in December, with a rise of 4.6% on the previous month to make up 15.1% of new loans. This is faster than for non-first time buyer loans, here the number of loans grew 3.1%. The average loan size fell a little in the month, reflecting tighter lending criteria. This is original data, not trend smoothed. Overlaying first time investors, from our surveys, overall first time buyers were more active, still wanting to get on the property ladder one way or the other. FTB investors grew by 6.5% in the month, after a couple of slow months before. Overall, about 14,000 first time buyer deals were done.

Overlaying first time investors, from our surveys, overall first time buyers were more active, still wanting to get on the property ladder one way or the other. FTB investors grew by 6.5% in the month, after a couple of slow months before. Overall, about 14,000 first time buyer deals were done.