APRA Chairman Wayne Byers gave the keynote address at the COBA 2017 – Customer Owned Banking Convention in Brisbane. It included some remarks on the state of play of housing lending standards making the point that until recently, systematically, lending standards were eroding, but this is now being reversed. He specifically mentioned a desire for borrower debt-to-income levels to be appropriately constrained in anticipation of (eventually) rising interest rates.

We would say better late than never!

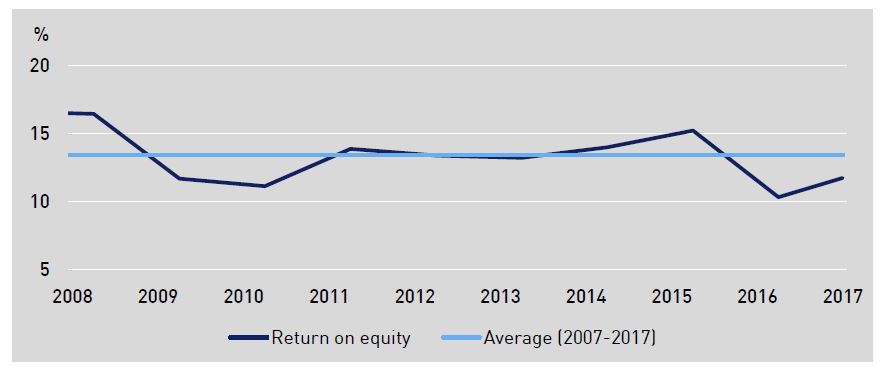

Earlier this year, we announced further measures to reinforce prudent standards across the industry. We did this because, in our view, risks and practices were still not satisfactorily aligning. We remain in an environment of high house prices, high and rising household indebtedness, low interest rates, and subdued income growth. That environment has existed for quite a few years now, and one might expect a prudent banker to tighten lending standards in the face of higher risk. But for some years standards had, absent regulatory intervention, been drifting the other way. Indeed, if we look back at standards that the industry thought important a decade ago, we see aspects of prudent practice that we are trying to re-establish today.

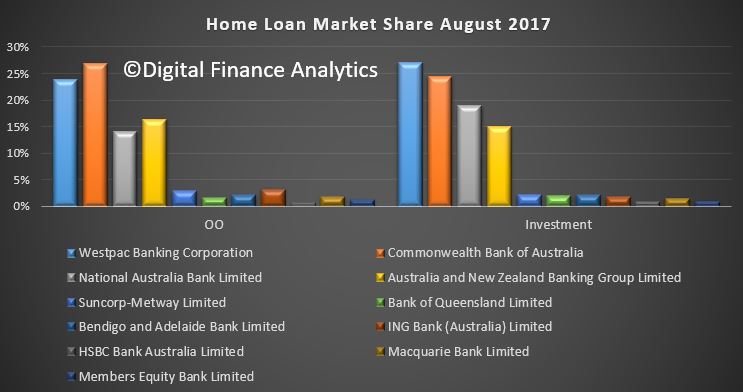

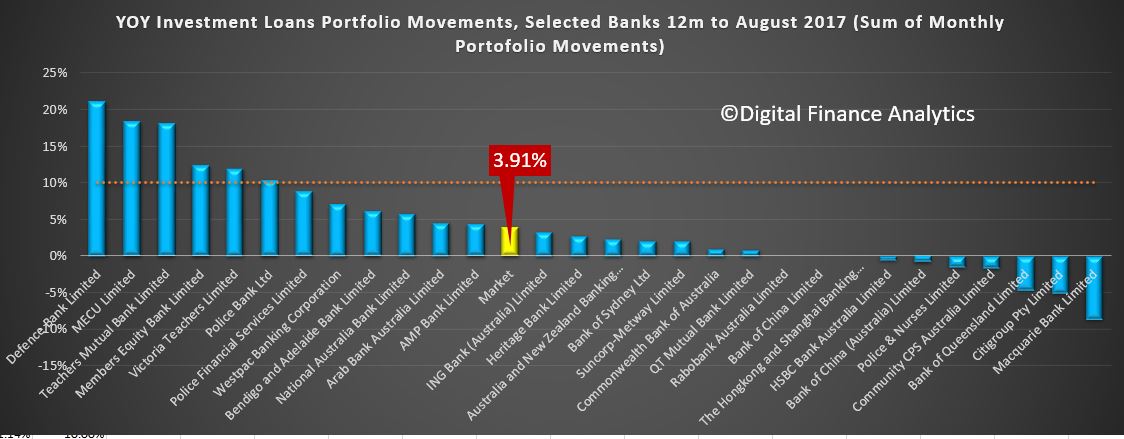

The erosion in standards has been driven, first and foremost, by the competitive instincts of the banking system. Many housing lenders have been all too tempted to trade-off a marginal level of prudence in favour of a marginal increase in market share. That temptation has, unfortunately, been widespread and not limited to a few isolated institutions – the competitive market pushes towards the lowest common denominator. The measures that we have put in place in recent years have been designed, unapologetically, to temper competition playing out through weak credit underwriting standards.

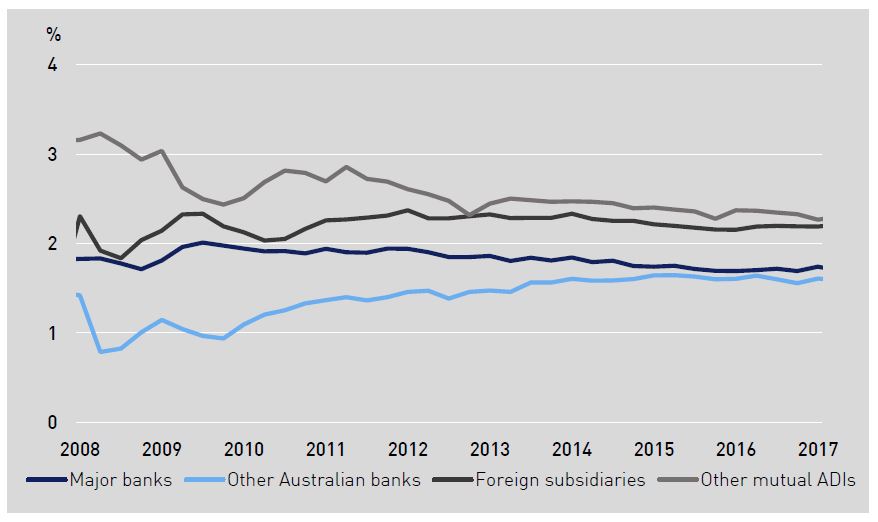

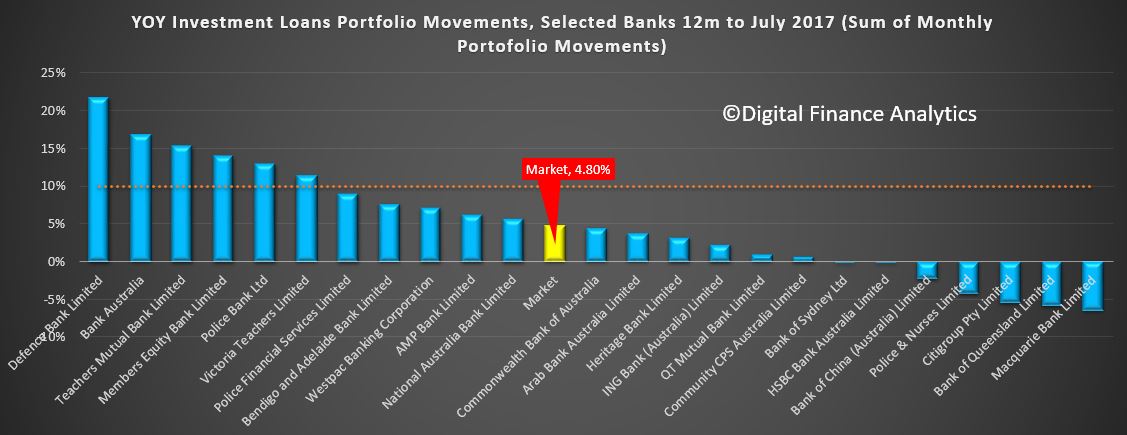

Since we have been focussing on lending standards, APRA’s approach has been consistently industry-wide: the measures apply to all ADIs, albeit with additional flexibility for smaller, less systemic players around the timing and manner in which they have been expected to adjust practices. There is no reason, however, why poor quality lending should be acceptable for some ADIs and not others, or in one geography and not others. Prudent standards are important for all.

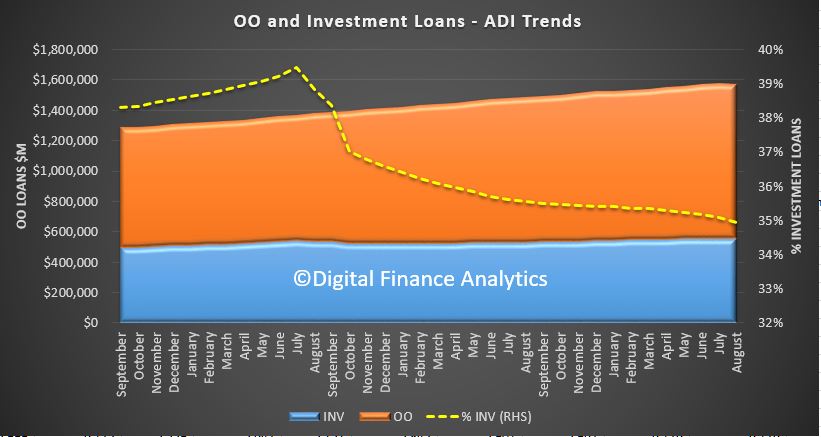

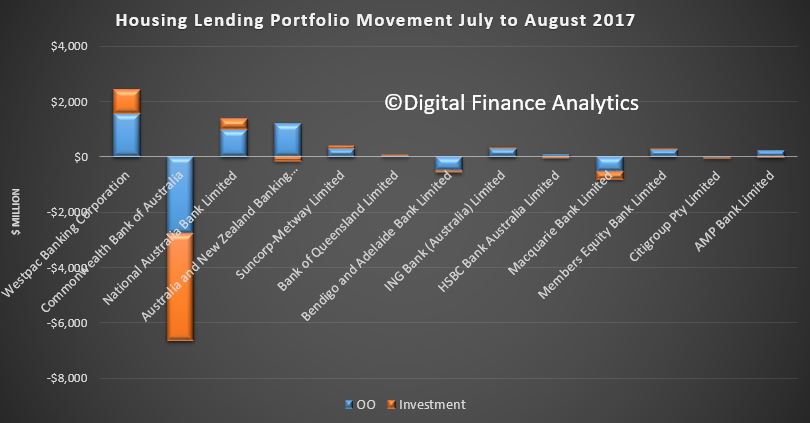

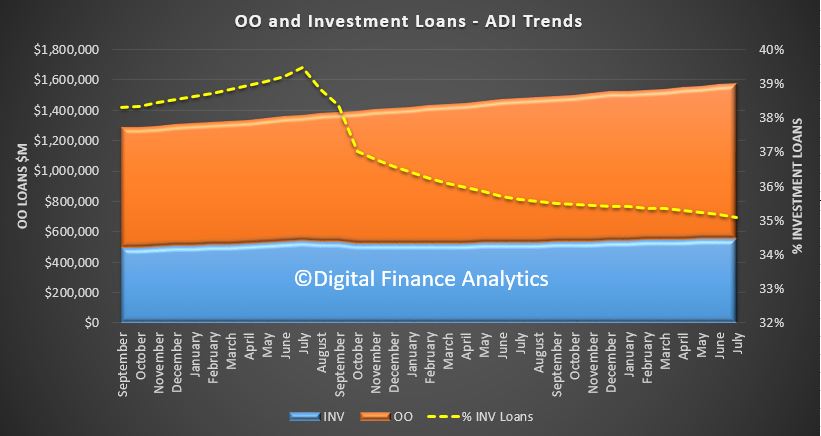

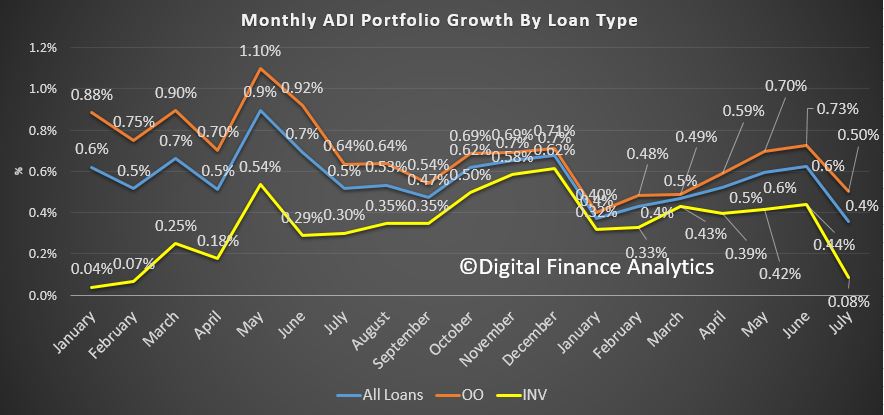

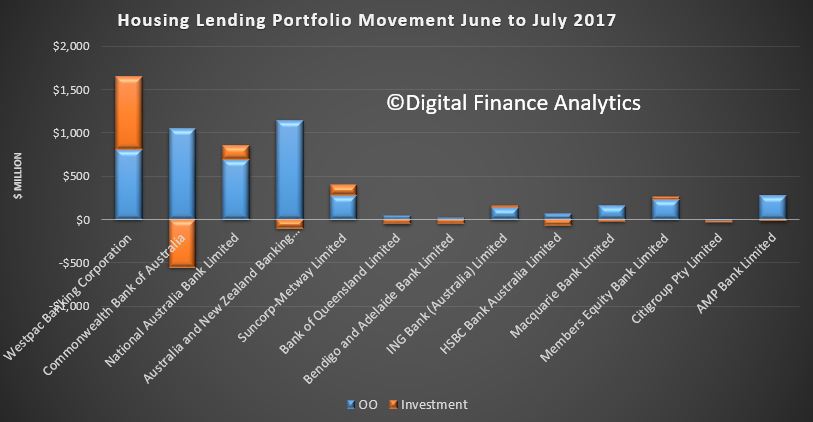

At a macro level, our efforts appear to be having a positive impact. As I have spoken about previously, serviceability assessments have strengthened, investor loan growth has moderated and high loan-to-valuation lending has reduced. New interest-only lending is also on track to reduce below the benchmark that we set earlier this year. Put simply, the quality of lending has improved and risk standards have strengthened.

We would ideally like to start to step back from the degree of intervention we are exercising today. Quantitative benchmarks, such as that on investor lending growth, have served a useful purpose but were always intended as temporary measures. That remains our intent, but for those of you who chafe at the constraint, their removal will require us to be comfortable that the industry’s serviceability standards have been sufficiently improved and – crucially – will be sustained. We will also want to see that borrower debt-to-income levels are being appropriately constrained in anticipation of (eventually) rising interest rates.

These expectations apply across the industry, to large and small alike. Pleasingly, the industry is moving in the right direction to achieve that. Improved serviceability standards are being developed, and policy overrides are being monitored more thoroughly and consistenly. The adoption of positive credit reporting, which APRA strongly endorses, will remove a blind spot in a lender’s ability to see a borrower’s leverage. Coupled with the higher and more risk-sensitive capital requirements that I mentioned earlier, these developents should – all else being equal – provide an environment in which some of our benchmarks are no longer needed. The review of serviceabilitiy standards across the small ADI sector that we are currently undertaking will help inform our judgement as to how close we are to that point.

His comments on the role of mutual ADI’s are are worth reading…