The APRA Monthly banking statistics for January 2016 came out today. Whilst overall ADI lending for housing grew 0.6%, lending for owner occupation grew 0.9%, from $898 bn in December to $906 billion in January. Much of this will be refinancing of existing loans, and some first time buyer activity. Investment lending grew very slightly. However, there was a $1.4 bn adjustment between OO and investment loans, so the splits are not that reliable. So, whilst lending may be slowing a little, there was significant momentum in the market in January. Total lending reached $1,424 bn, up by $8.1 bn.

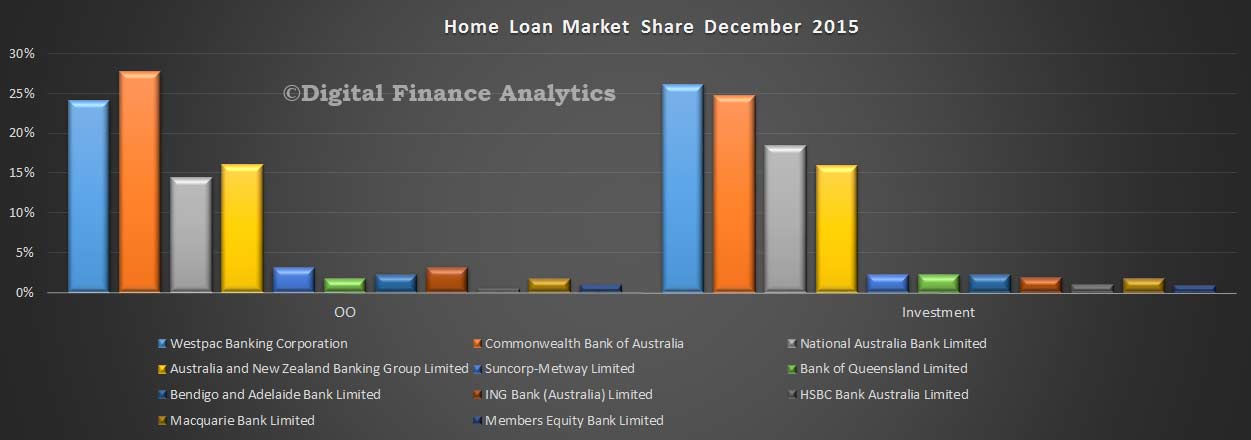

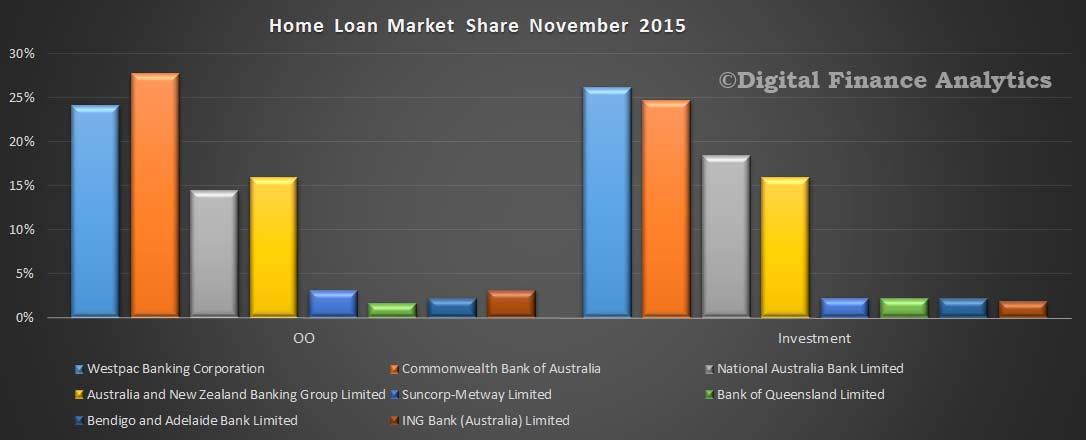

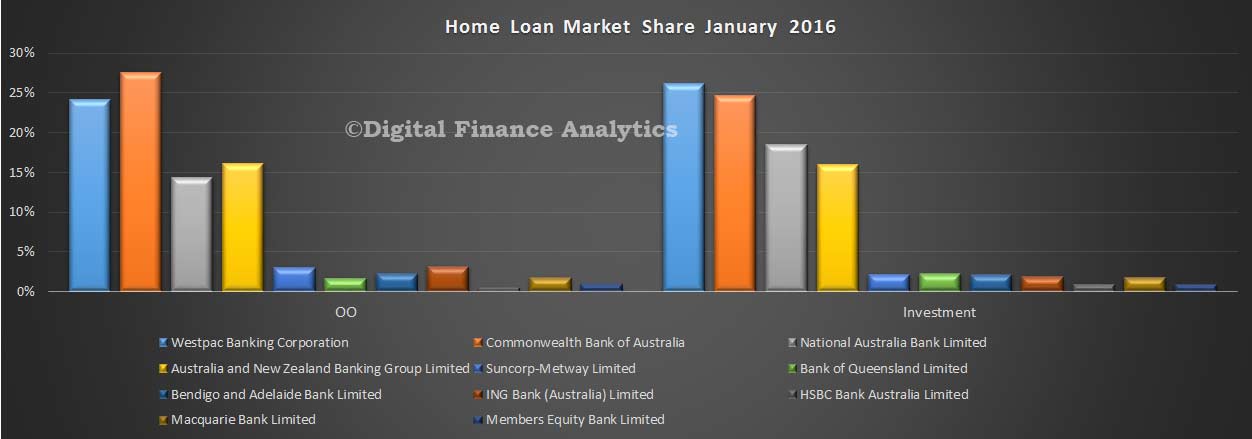

Looking at the individual banks, the market shares did not change that much, with CBA holding 27.6% of owner occupied loans, whilst Westpac holds 26.13% of investment loans.

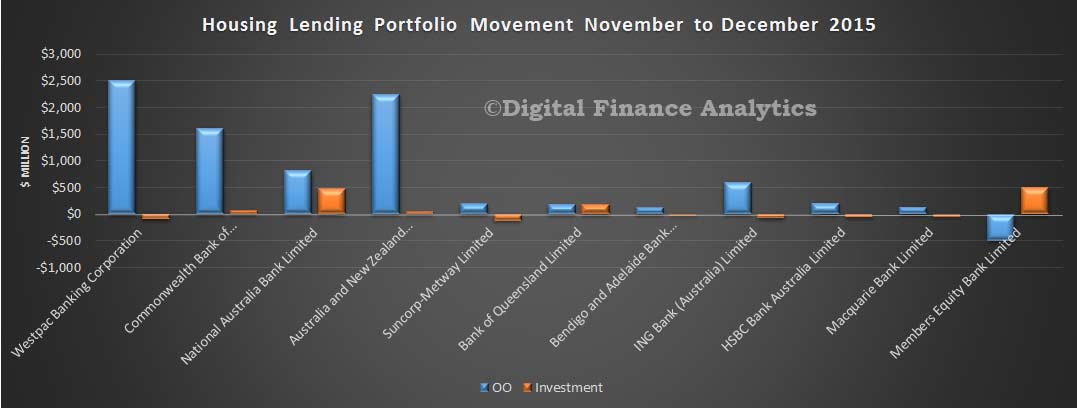

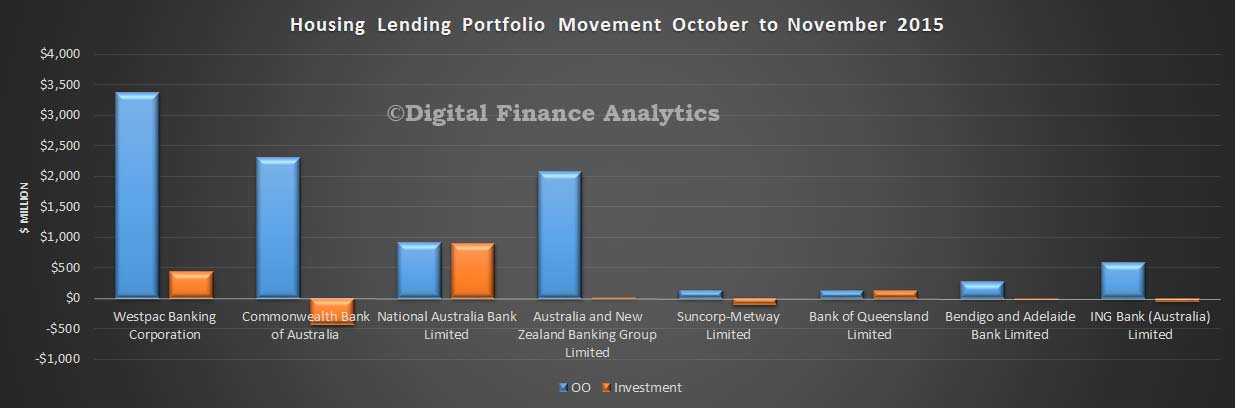

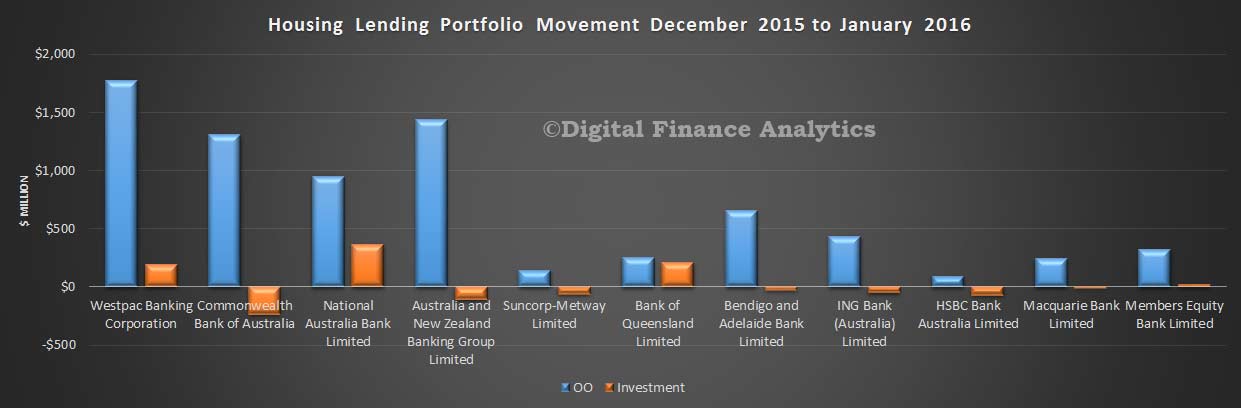

The portfolio movements (which are not adjusted for reclassifications between OO and investment loans) highlights growth in OO loans across the board. Movements in investment loans is more patchy.

The portfolio movements (which are not adjusted for reclassifications between OO and investment loans) highlights growth in OO loans across the board. Movements in investment loans is more patchy.

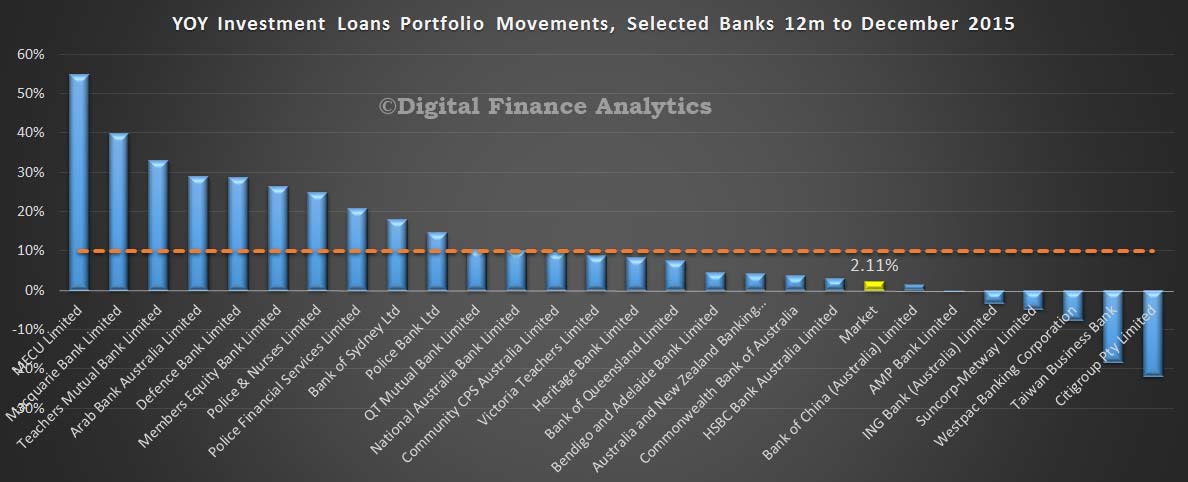

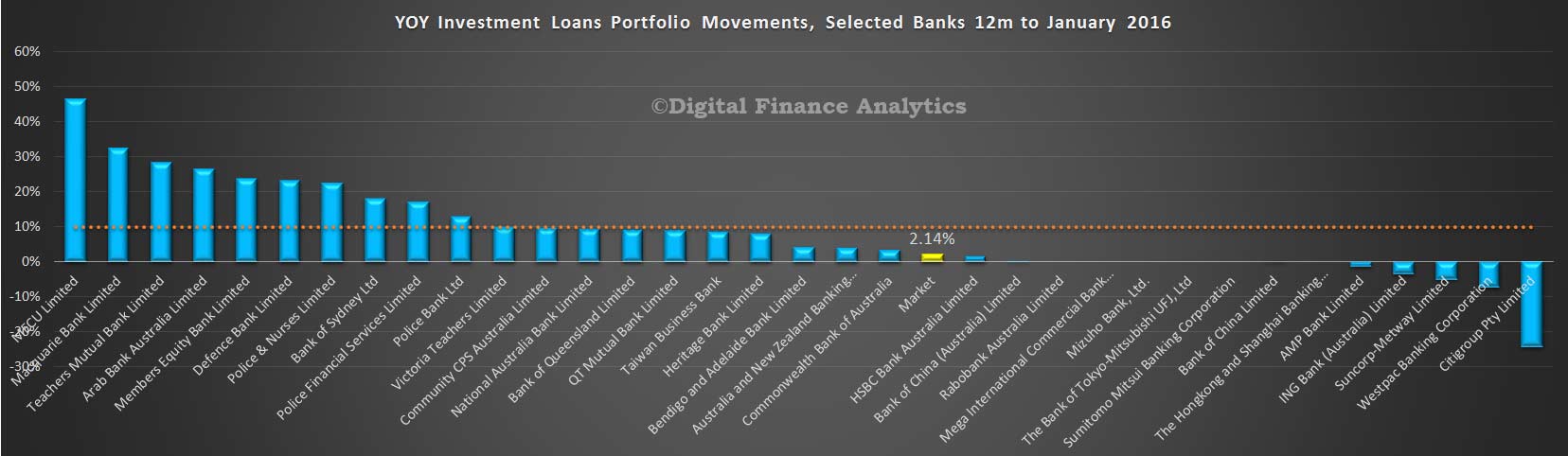

For what it is worth (and we have consistently used the monthly data, adjusted where we can), we see that market growth in investment loans is now sitting at 2.14%, for the 12 months to January 2016. The big four are all below the APRA 10% speed limit. Others, for various reasons are still speeding.

For what it is worth (and we have consistently used the monthly data, adjusted where we can), we see that market growth in investment loans is now sitting at 2.14%, for the 12 months to January 2016. The big four are all below the APRA 10% speed limit. Others, for various reasons are still speeding.

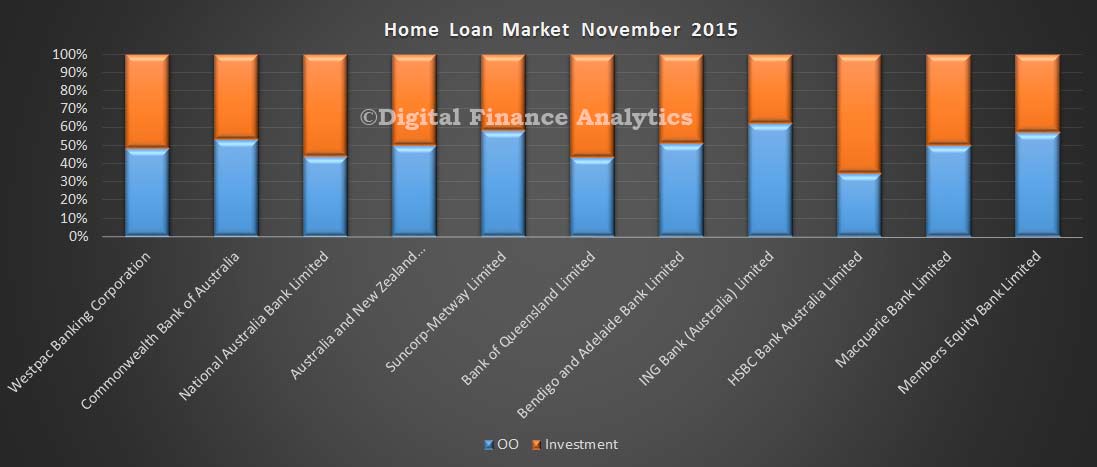

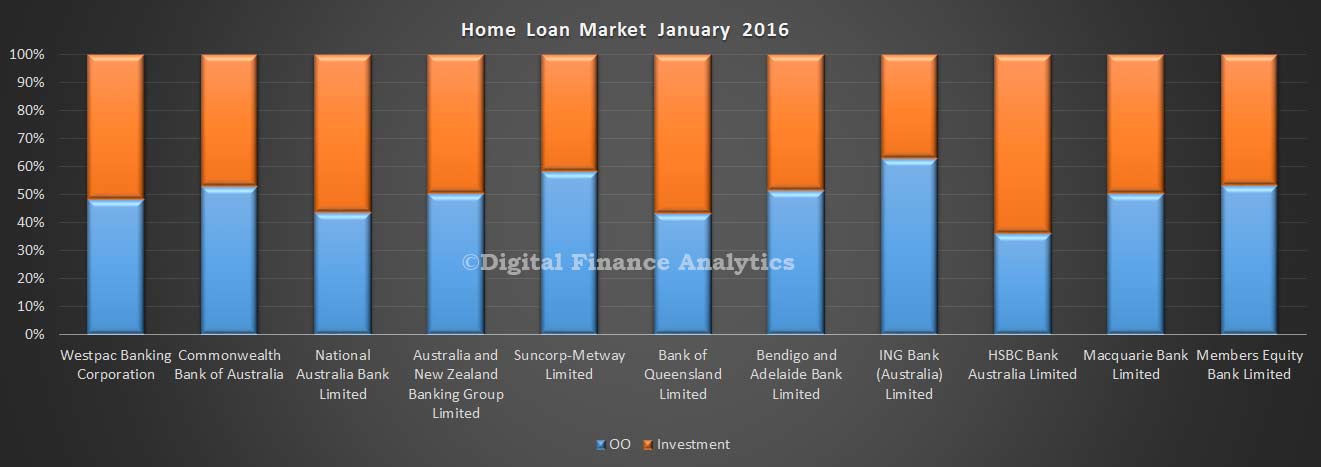

The splits between OO and investment lending varies by lender, with HSBC, Bank of Queensland and NAB holding the larger proportion of investment loans, expressed as relative market shares.

The splits between OO and investment lending varies by lender, with HSBC, Bank of Queensland and NAB holding the larger proportion of investment loans, expressed as relative market shares.

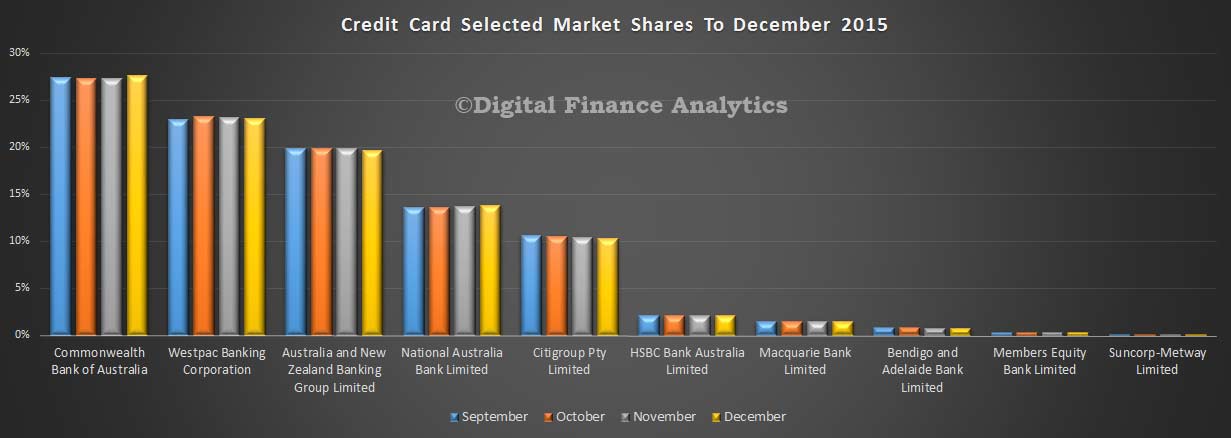

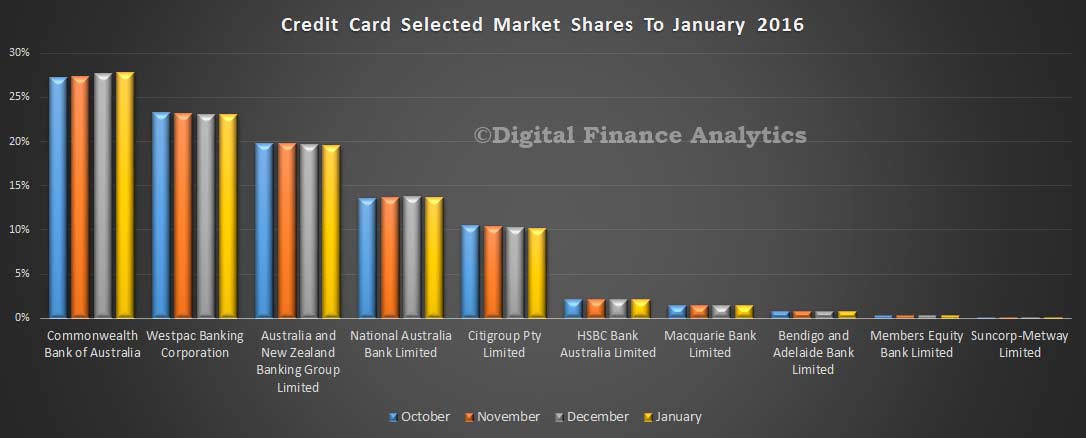

Tuning to credit cards, total balances fell $747m in the month, to $41 billion. CBA is growing its relative share of cards, with 27.8% of the market. NAB also grew slightly in relative terms, whilst ANZ and WBC fell a little.

Tuning to credit cards, total balances fell $747m in the month, to $41 billion. CBA is growing its relative share of cards, with 27.8% of the market. NAB also grew slightly in relative terms, whilst ANZ and WBC fell a little.

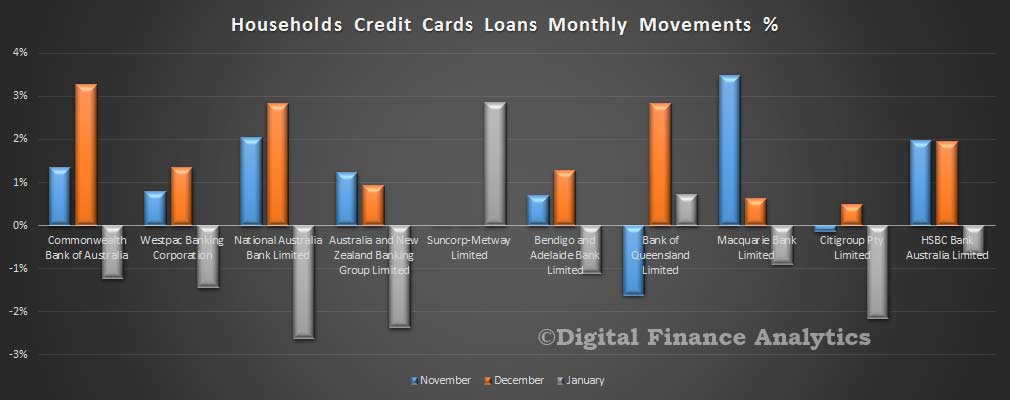

Looking at the monthly movements, we see that households are paying down loans they took over the Christmas.

Looking at the monthly movements, we see that households are paying down loans they took over the Christmas.

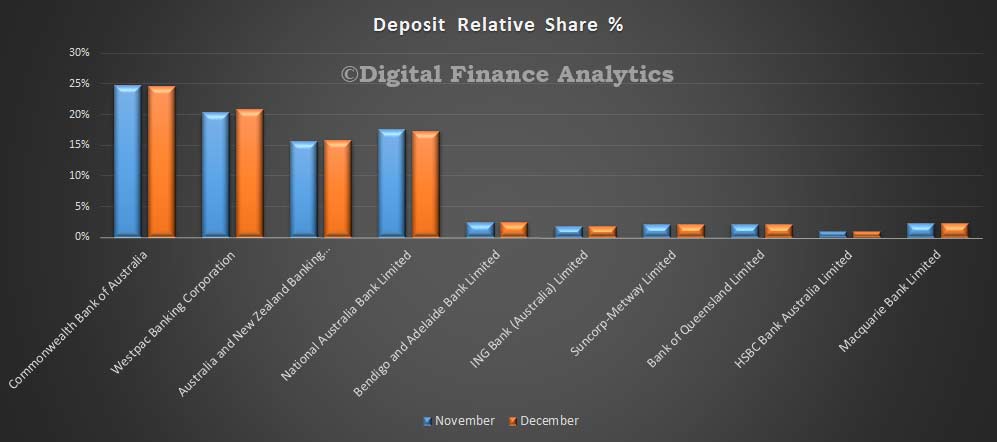

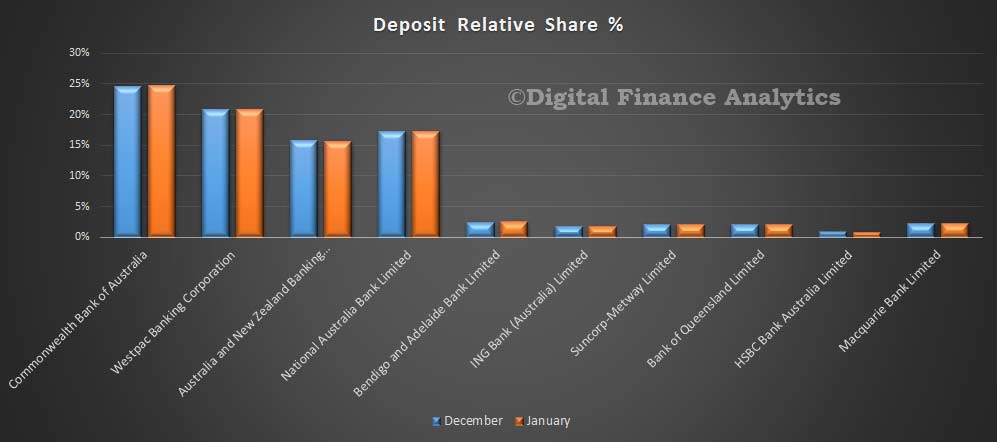

Turning to deposits, total deposits grew 0.8% to $1.92 trillion. CBA grew its share a little, from 24.6% to 24.8% and remains the largest holder of deposits in Australia.

Turning to deposits, total deposits grew 0.8% to $1.92 trillion. CBA grew its share a little, from 24.6% to 24.8% and remains the largest holder of deposits in Australia.

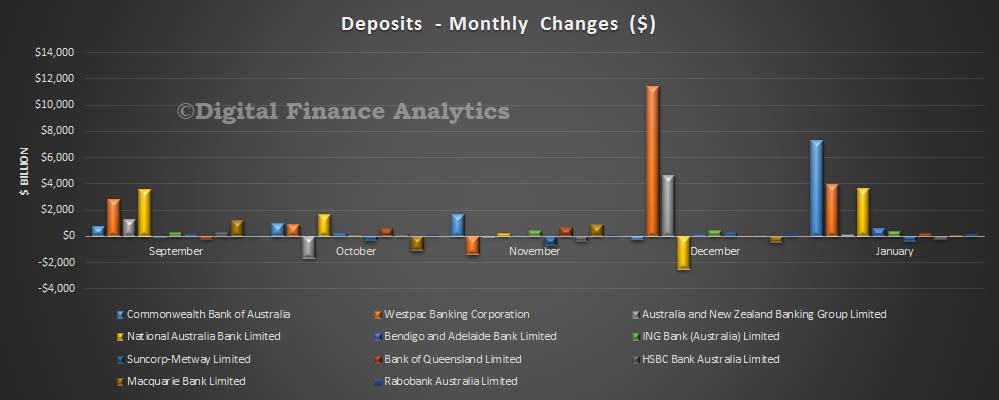

ANZ lost a little share in the month as it attracted less money in than the other three majors. CBA lifted net balances by $7.3 bn, compared with WBC’s $3.9 bn and NAB’s 3.6 bn.

ANZ lost a little share in the month as it attracted less money in than the other three majors. CBA lifted net balances by $7.3 bn, compared with WBC’s $3.9 bn and NAB’s 3.6 bn.

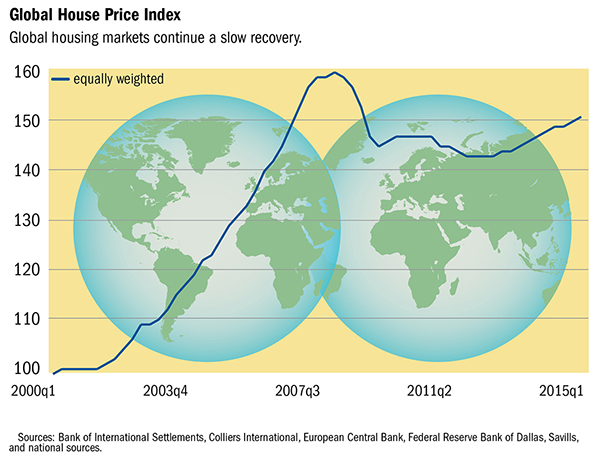

Given the higher margins on overseas funding at the moment, with speads elevated thanks to a range of global uncertainties, local deposits are more valuable, and we expect to see some strong competition for balances in the months ahead.

Given the higher margins on overseas funding at the moment, with speads elevated thanks to a range of global uncertainties, local deposits are more valuable, and we expect to see some strong competition for balances in the months ahead.