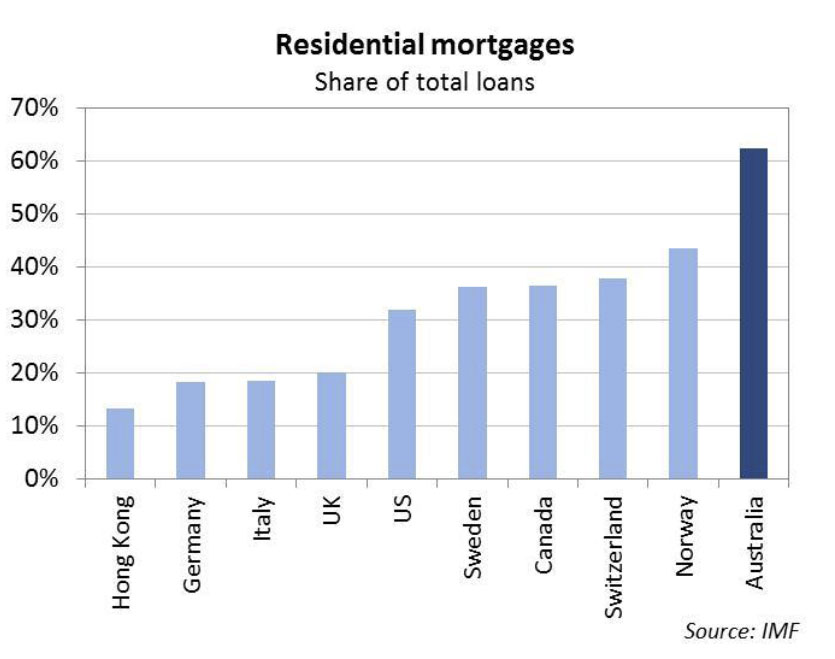

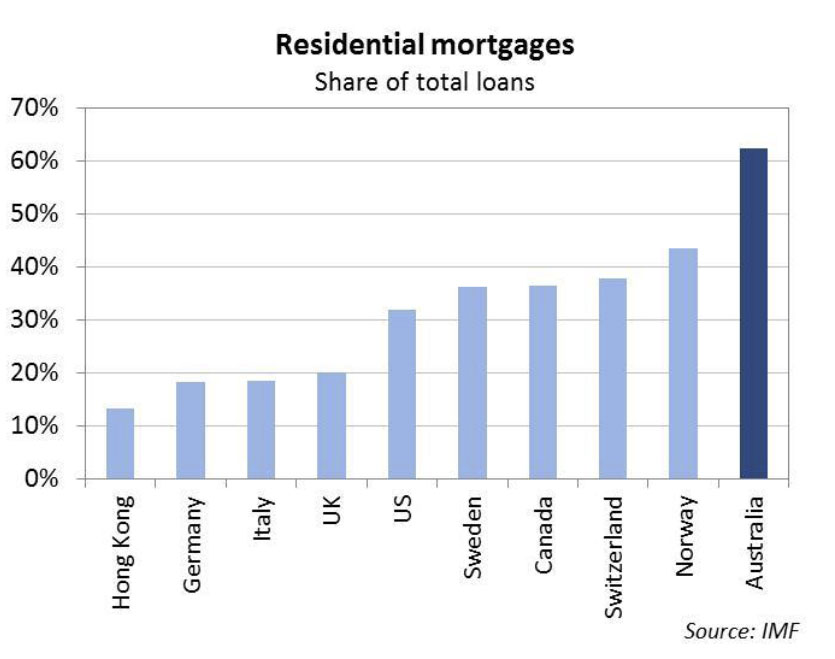

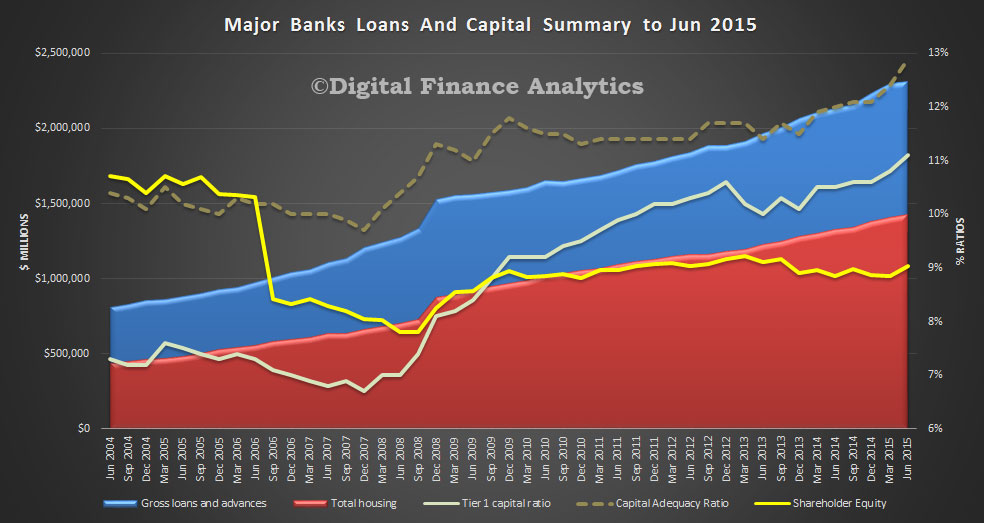

Wayne Byres, Chairman APRA, “Banking On Housing“, speech today, portrayed the current state of play with regards to supervision of housing lending. He started by noting that housing lending now accounts for around 40 per cent of banking industry assets, and a little under two-thirds of the aggregate loan portfolio. With such a concentration in a single business line, we are all banking on housing lending remaining ‘as safe as houses’.

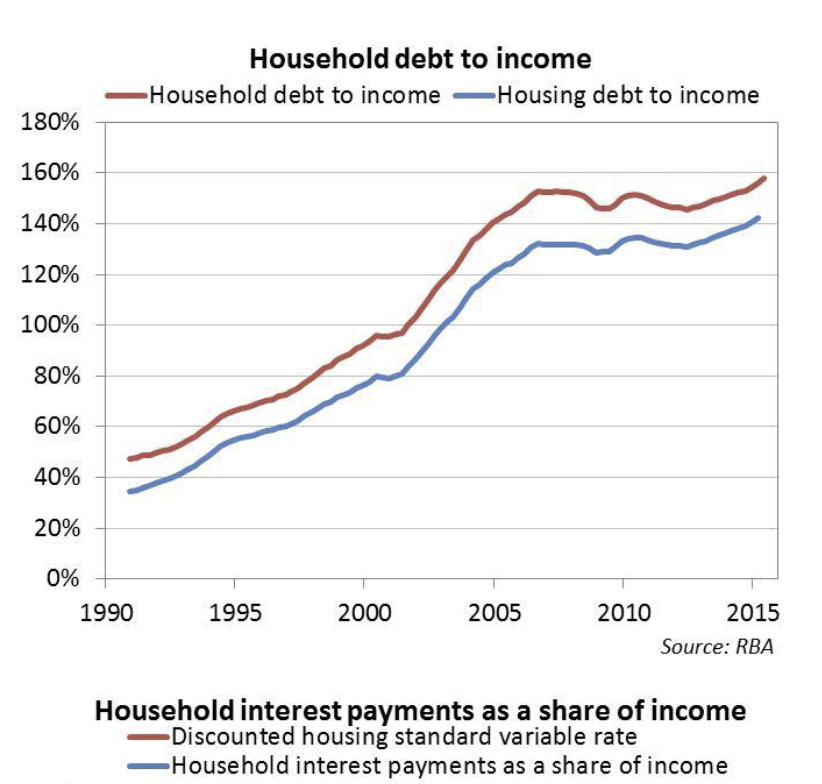

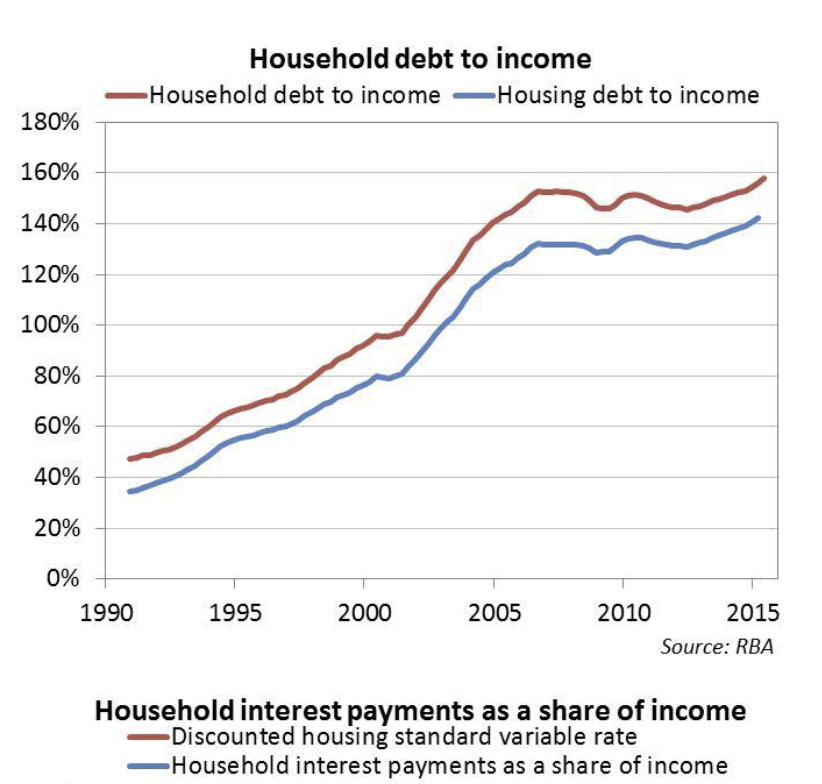

Supervision is important, he say’s given the high household debt involved. As with housing prices, these debt levels are at the higher end of the spectrum. Furthermore, after plateauing for much of the past decade, the household debt-to-income ratio has begun drifting upwards again. Households still have a significant (and growing) net worth, as housing assets are increasing in value faster than debt. Nevertheless, the trends in overall level of debt bear watching.

Supervision is important, he say’s given the high household debt involved. As with housing prices, these debt levels are at the higher end of the spectrum. Furthermore, after plateauing for much of the past decade, the household debt-to-income ratio has begun drifting upwards again. Households still have a significant (and growing) net worth, as housing assets are increasing in value faster than debt. Nevertheless, the trends in overall level of debt bear watching. He acknowledges the change in mix of loans, with the growth of investor loans.

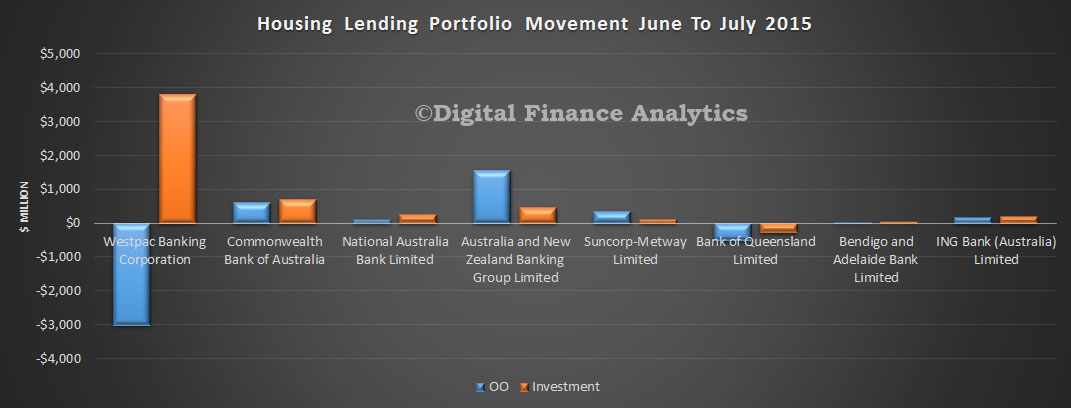

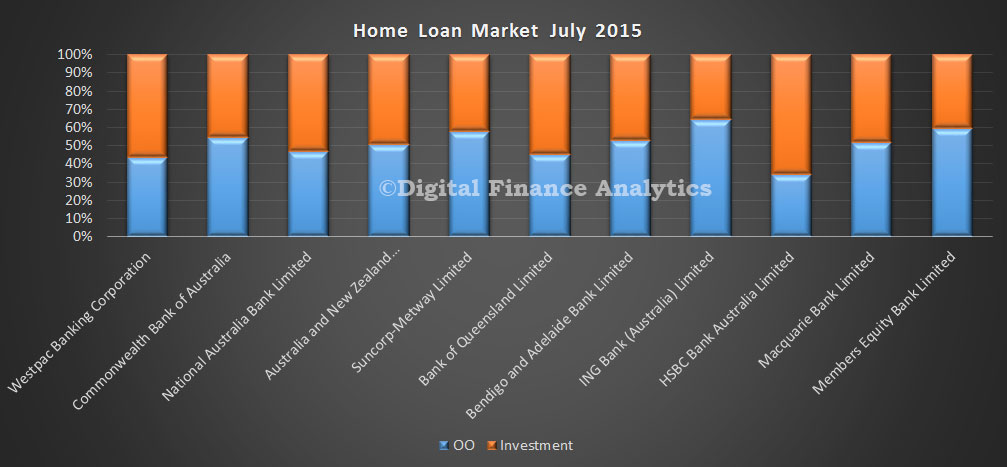

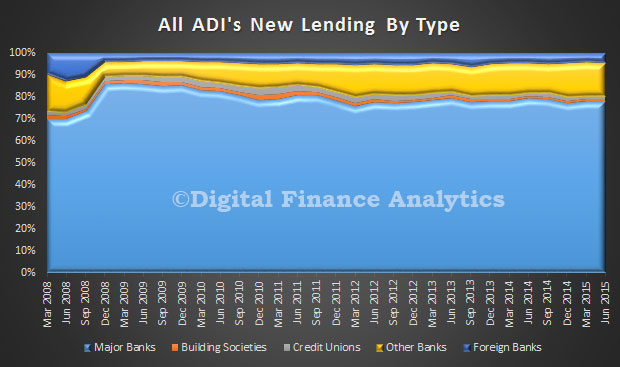

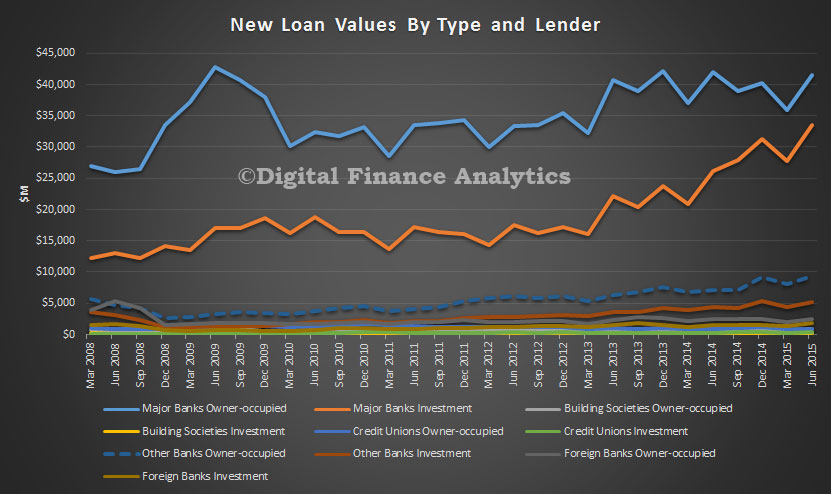

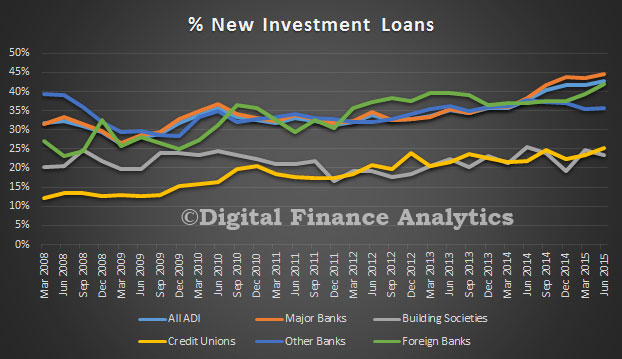

He acknowledges the change in mix of loans, with the growth of investor loans.

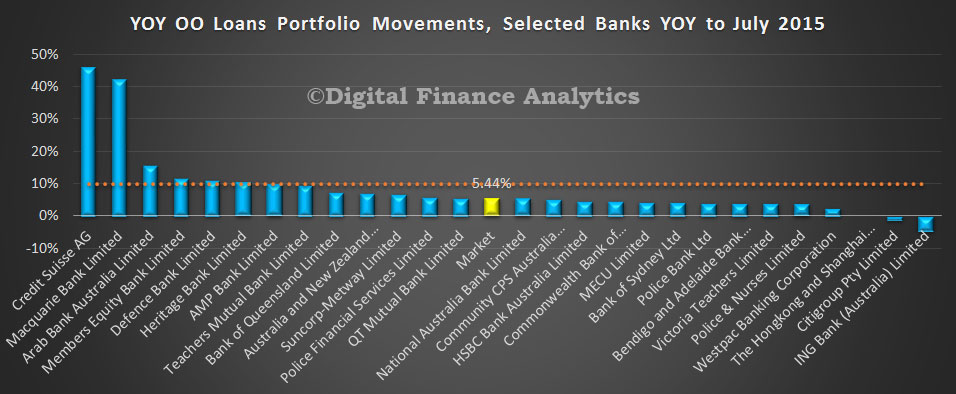

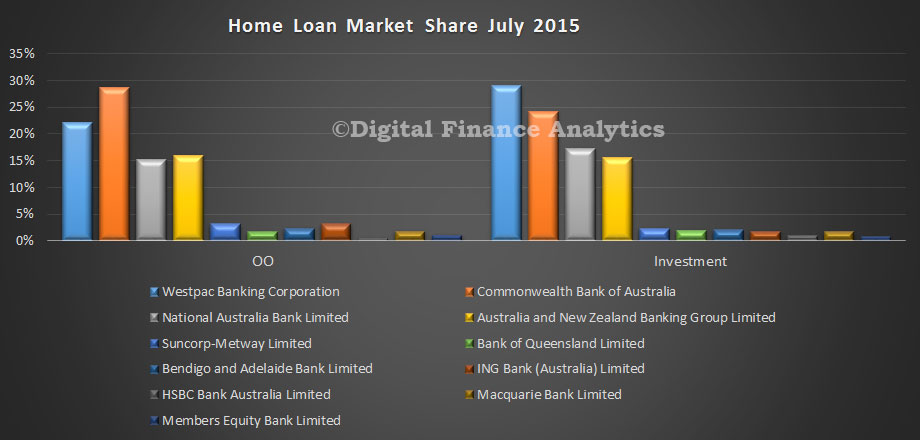

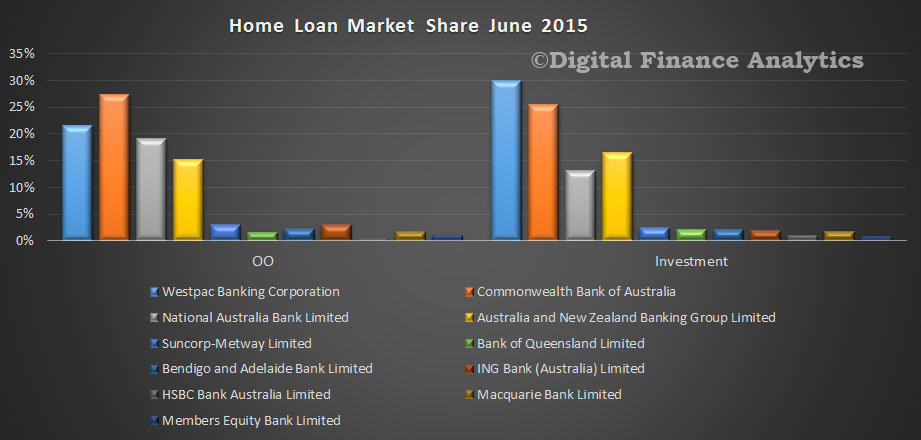

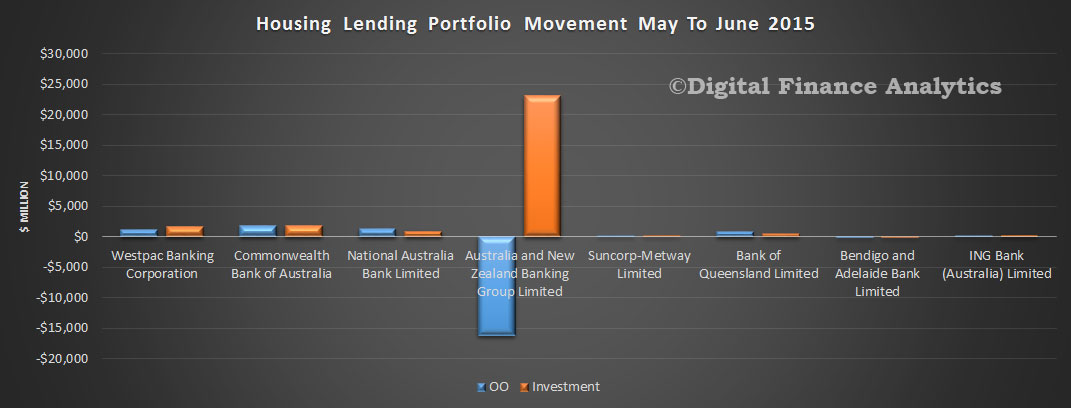

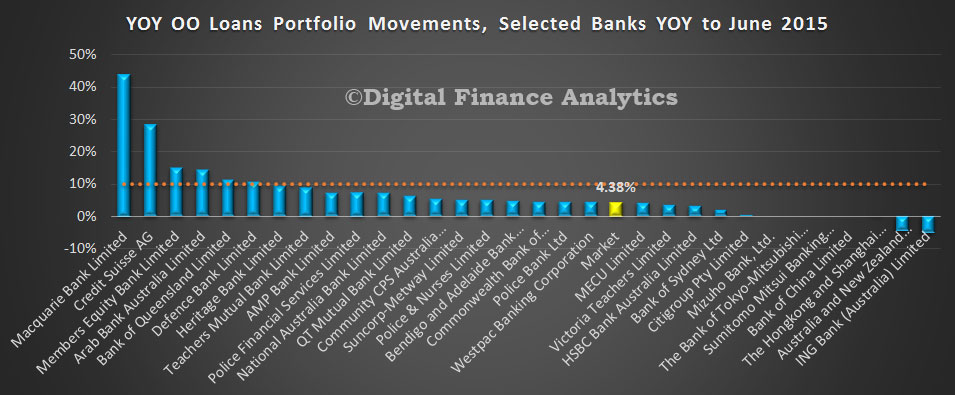

Turning to the composition of loan portfolios, a notable change has been the well-publicised growth in lending to investors. In terms of the outstanding stock of housing lending, investors account for more than one-third; of the current flow of approvals, investors now account for more than 40 per cent. For comparison, in the mid-1990’s both those proportions were around half today’s levels.

A key question is: does this compositional shift change portfolio risk profiles? Australian data suggests that there has been little difference in the propensity of investor loans to become impaired, vis-à-vis those to owner-occupiers. However, caution is needed given the lack of any period of severe household stress over the past two decades: evidence from other countries suggests we should be wary of extrapolating the current Australian experience into more stressful scenarios.

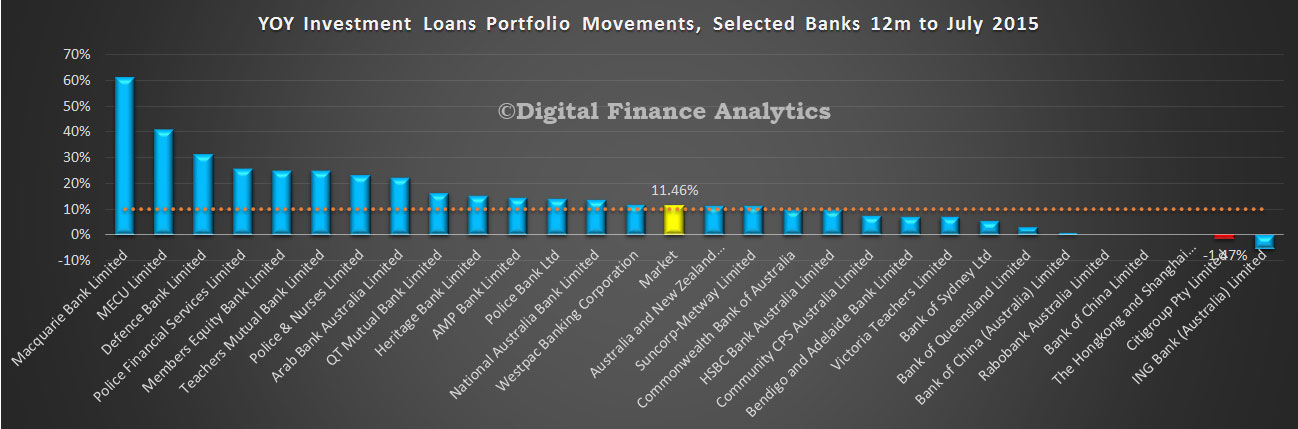

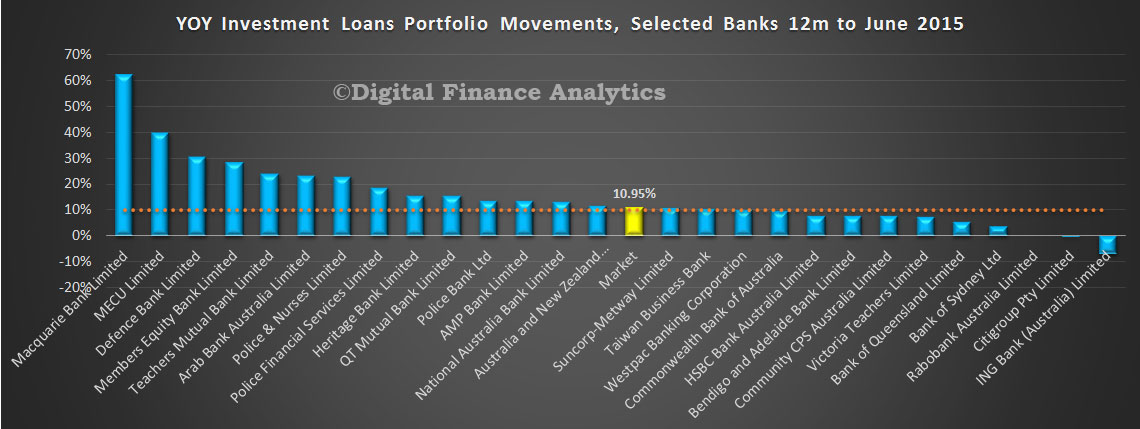

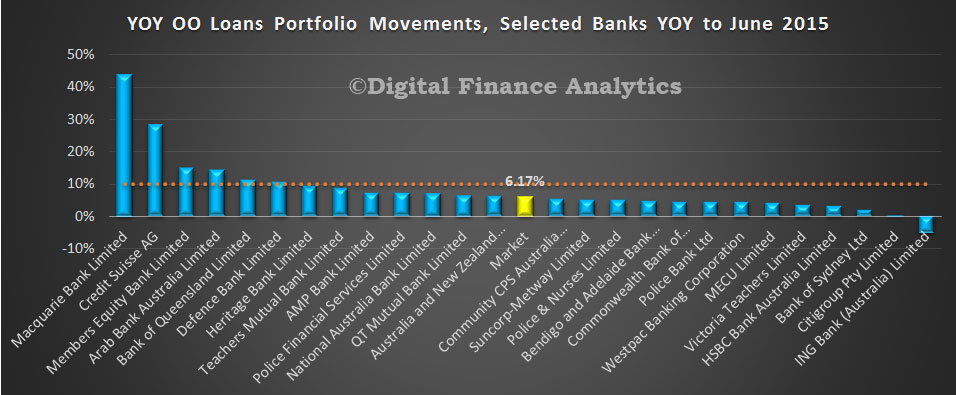

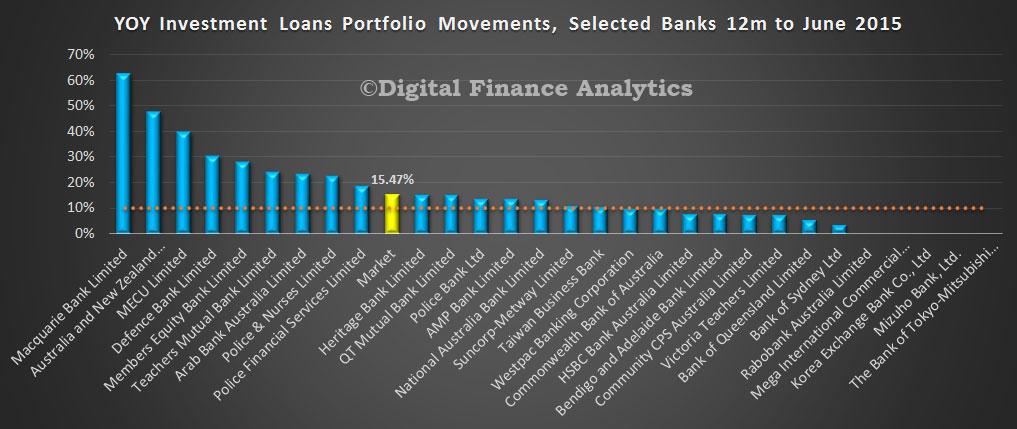

Of course, it is not just the nature of the borrower, but also the growth in lending, that acts as a warning sign for supervisors. When we wrote to ADIs in December 2014, we flagged a benchmark for investor lending growth of 10 per cent, or higher, as a sign of increased risk. We highlighted investor lending because it was an area of accelerating credit growth and strong competition: a combination in which the temptation to compete and protect market share could drive a weakening of credit standards. By moderating growth aspirations, we are reducing the tendency for ADIs to whittle away lending standards in the name of ‘matching our competitors’ – when it comes to lower standards, it’s always the other guy’s fault.

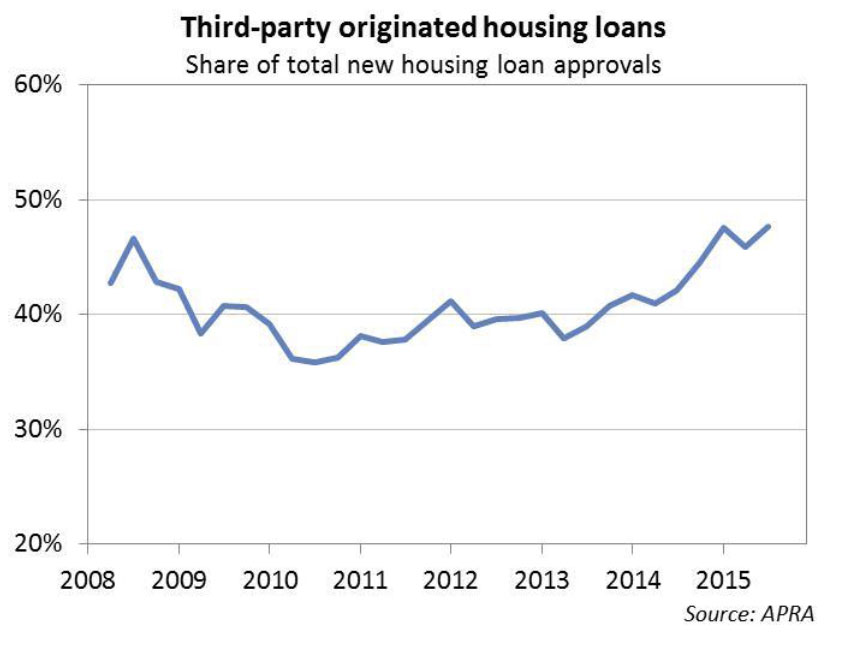

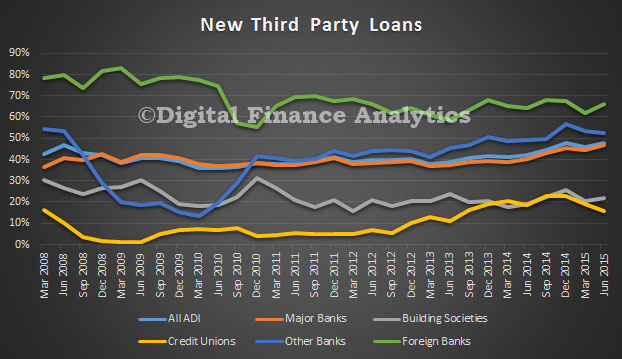

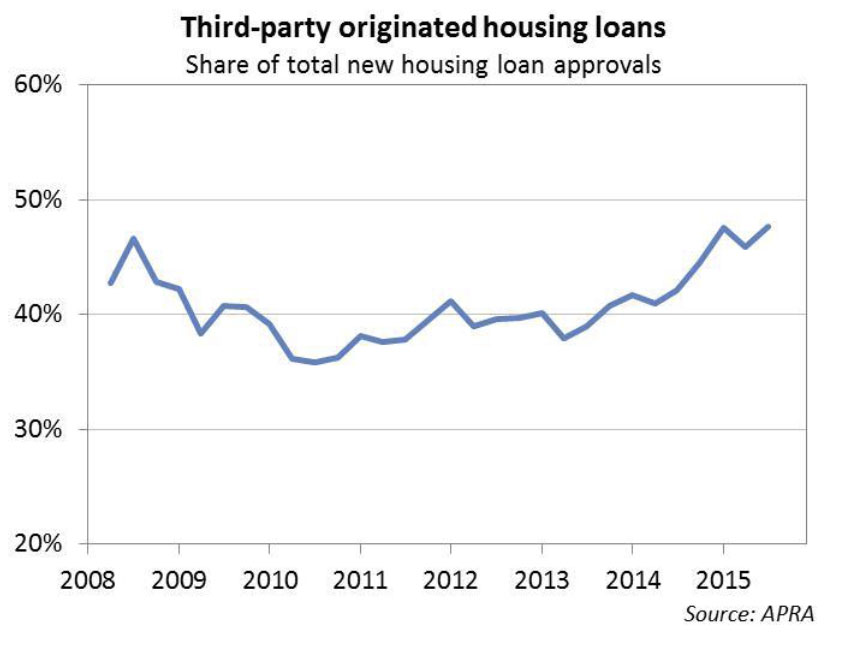

He highlighted the rising share of loans originated via brokers.

Another feature of the home lending market has been the increasing use of third-party distribution channels. There are potentially significant advantages from such an approach: for example, allowing smaller lenders or new entrants to compete more readily against the established branch networks of the bigger players. On the other hand, third-party-originated loans tend to have a materially higher default rate compared to loans originated through proprietary channels. This does not mean third-party channels have lower underwriting standards, but simply that the new business that flows through these channels appears to be of higher risk, and must be managed with appropriate care.

Another feature of the home lending market has been the increasing use of third-party distribution channels. There are potentially significant advantages from such an approach: for example, allowing smaller lenders or new entrants to compete more readily against the established branch networks of the bigger players. On the other hand, third-party-originated loans tend to have a materially higher default rate compared to loans originated through proprietary channels. This does not mean third-party channels have lower underwriting standards, but simply that the new business that flows through these channels appears to be of higher risk, and must be managed with appropriate care.

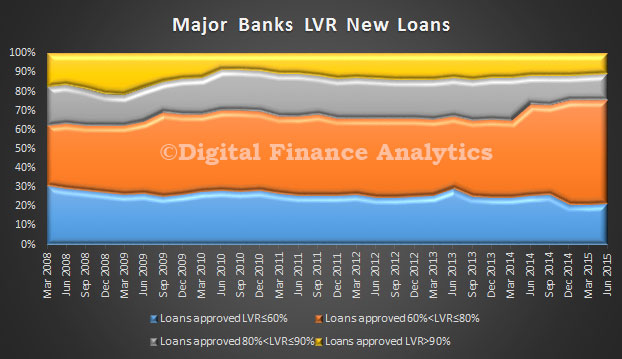

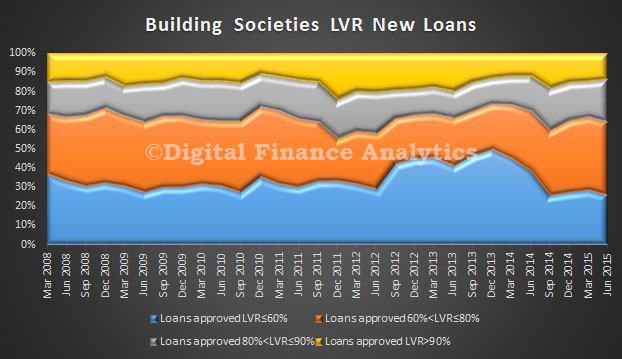

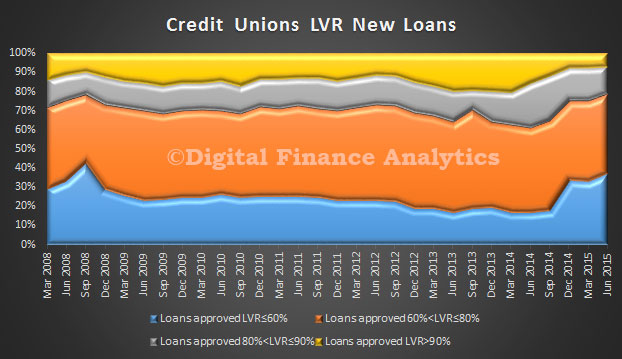

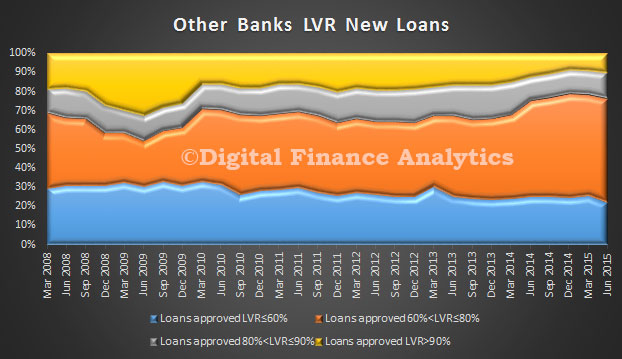

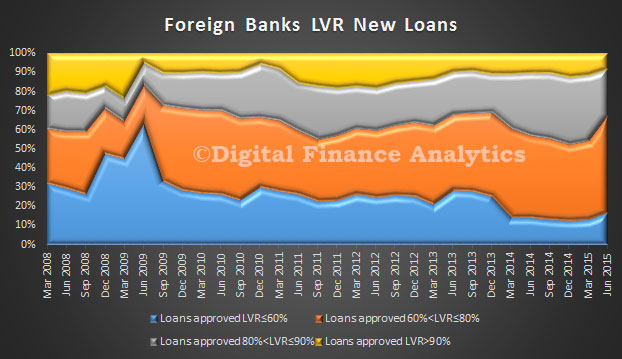

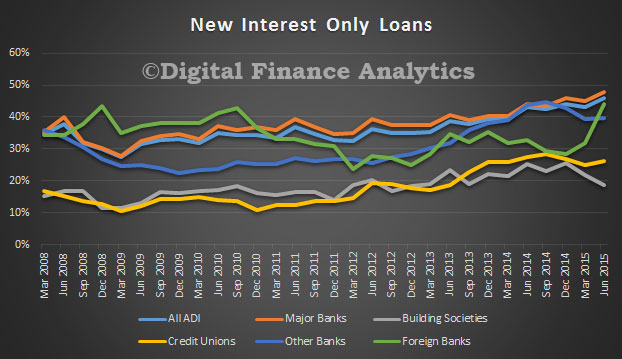

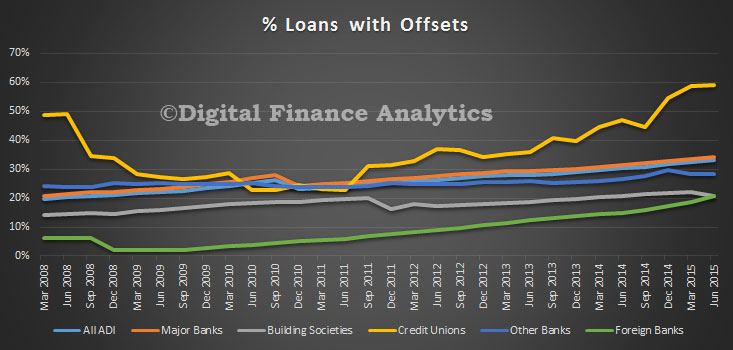

He also described the rise in interest only loans, and changes in LVR ratios as highlighted in yesterdays APRA data, which we discussed in detail already.

Finally, he discussed lending standards.

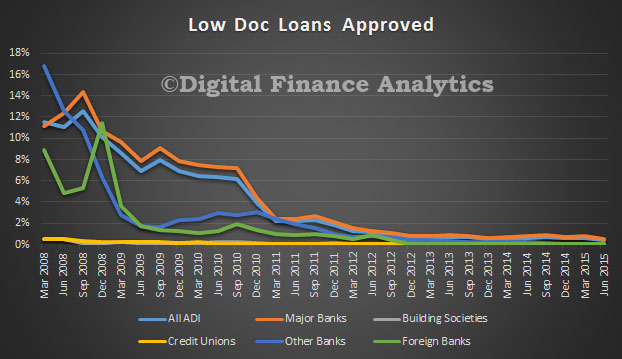

The final layer of analysis has been our detailed review of lending standards at individual lenders. We published some conclusions from this in May,6 and highlighted a few areas where standards were not what they could or should be. Examples included, generous interpretations of the stability and reliability of borrowers’ incomes; borrowers assumed to have very meagre living expenses; and/or a reliance on interest rates not rising very much, or (more puzzlingly) rising on new debts but not existing ones.

ASIC’s recently announced review of interest-only home lending made similar findings.

The industry has responded with improved practices in the past few months. For example, it is now commonplace for lenders to apply a haircut to unstable sources of income, and to assume a minimum interest rate of around 7.25 per cent – well above rates currently being paid – when assessing a borrower’s ability to service a loan. These steps should give greater comfort about the quality of new business now being written.

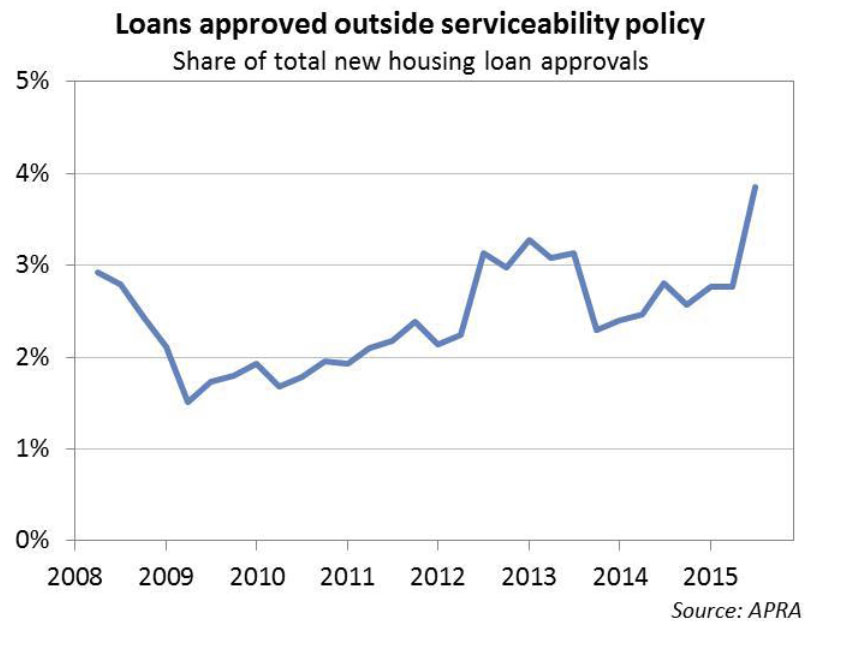

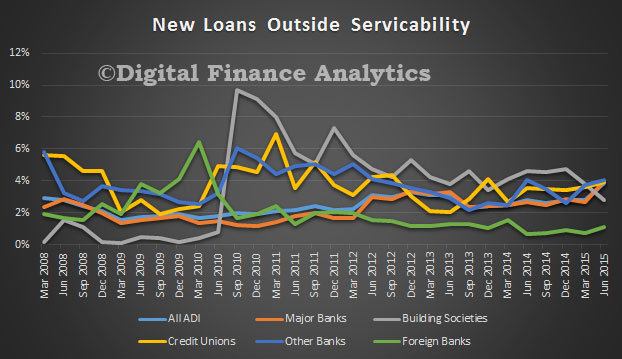

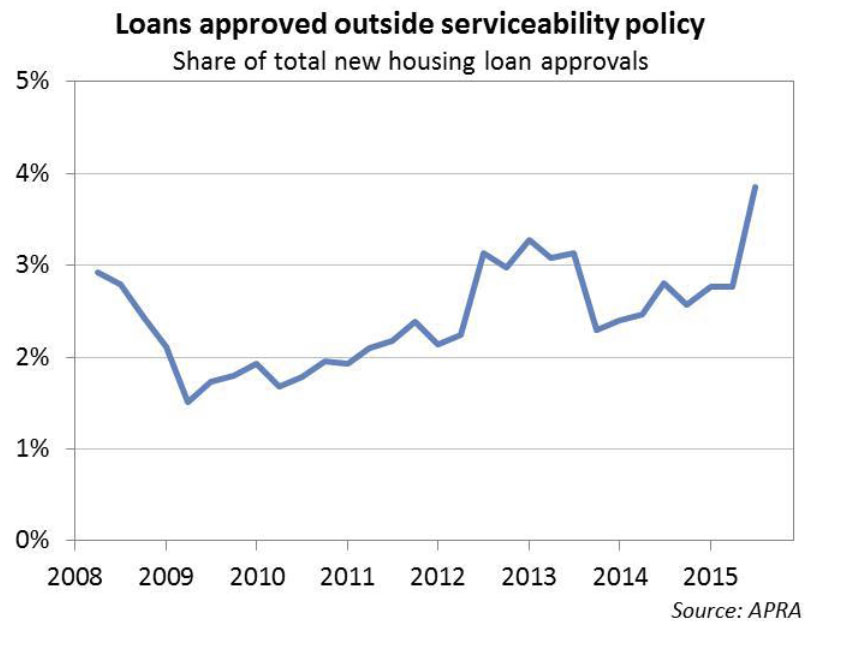

However, a close eye will need to kept on policy overrides – in other words, the extent to which lenders approve loans outside their standard policy parameters. There are some definitional issues that mean care is needed with this data, but the rising trend for loans to be approved outside policy needs to be watched: as lenders strengthen their lending policies, it’s important to make sure this good intent isn’t being undone by an increasing number of policy exceptions.

Before I wrap up, I’d like to comment on the potential for further action by APRA, including targeted measures that, it has been suggested, we should employ to specifically respond to rising housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne. In response, I would make three points:

Before I wrap up, I’d like to comment on the potential for further action by APRA, including targeted measures that, it has been suggested, we should employ to specifically respond to rising housing prices in Sydney and Melbourne. In response, I would make three points:

First, our mandate is to preserve the resilience of the banking system, not to influence prices in particular regions; second, the broader environmental factors I outlined at the start of my remarks – high housing prices, high debt levels, low interest rates and subdued income growth – are not present only in our two largest cities; and

third, sound lending standards – prudently estimating borrower income and expenses, and not assuming interest rates will stay low forever – are just as important (and maybe even more so) in an environment where price growth is subdued as they are in markets where prices are rising quickly.

That is not to say that geographic measures would never be contemplated. Parallels are often drawn with New Zealand, where specific measures have been directed at the rapid price appreciation in Auckland. In comparing the respective actions on both sides of the ditch, it’s important to note the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) initiated measures for Auckland only after first instituting a range of measures that applied New Zealand-wide. In other words, more targeted measures built on, rather than substituted for, measures to reduce financial stability risks nationally.

Given many changes to lenders’ policies, practices and pricing are still relatively recent, it is too early to say whether further action might be needed to preserve the resilience of the banking system. We remain open to taking additional steps if needed, but from my perspective the best outcome will be if lenders themselves maintain a healthy dose of common sense in their lending practices, and reduce the need for APRA to do more.

He concluded that APRA was still thinking about how to define ‘unquestionably strong’ and the role of top quartile positioning and made five closing points.

He concluded that APRA was still thinking about how to define ‘unquestionably strong’ and the role of top quartile positioning and made five closing points.