I’d like to use my time today to talk about two issues of relevance to all ADIs: credit risk and capital. In the world of banking supervision, these are at the heart of what we do: credit risk because it is far and away the biggest risk that ADIs take on, and capital because it is a critical form of defence for when those risks go awry. Sound lending and adequate capital do not guarantee long-run success, but they are certainly a precondition for it.

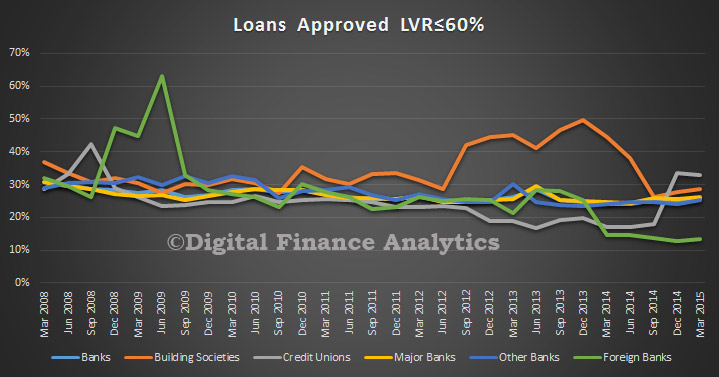

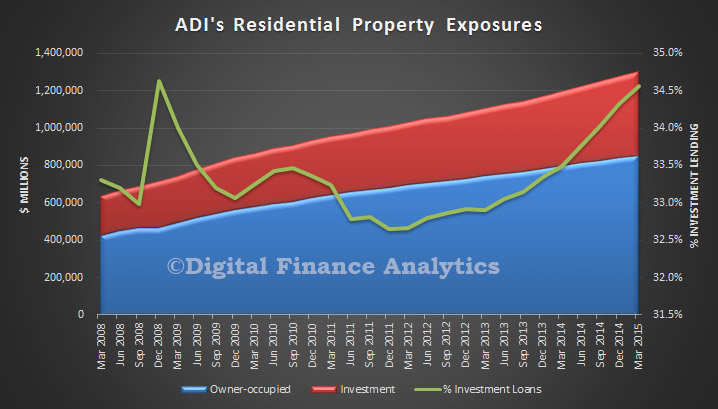

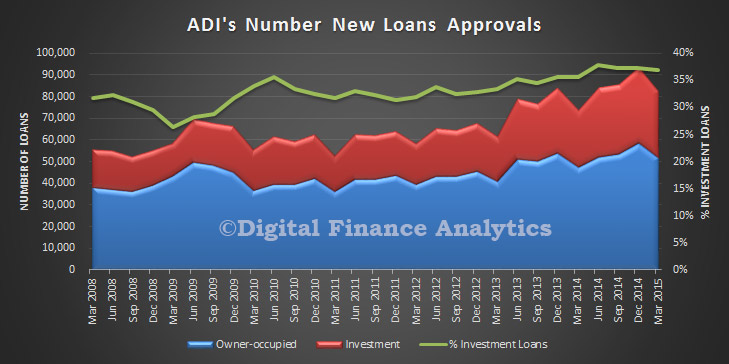

For many of you in the room today, the largest part of your loan portfolios is lending for housing. In that, you are reflective of the broader banking system in Australia. Across all ADIs, the proportion of lending attributable to housing has increased over the past decade from (an already dominant) 55 per cent to a little under 65 per cent today. For credit unions and building societies, the trend is directionally the same, but the dominance of housing even greater (Chart 1).

I have made the point elsewhere that the traditionally low risk nature of Australian housing portfolios has provided important ballast for the Australian banking system – a steady income stream and low loss rates from housing loan books have helped keep the system on a reasonably even keel, despite occasional stormy seas and misadventures elsewhere1. Much of the ongoing trust and confidence in the system, by Australian depositors and international investors alike, is founded on this history of stability.

It is not something we should place at risk.

The current economic environment for housing lenders is characterised by heightened levels of risk, reflecting a combination of historically low interest rates, high household debt, subdued income growth, unemployment that has drifted higher, significant house price growth, and strong competitive pressures. Many of these features have been emerging over a number of years, and APRA’s supervision has been intensifying in response. In addition to a heightened level of supervisory activity at individual ADIs, APRA has, for example:

- increased the level of analysis of mortgage portfolios, including regular review of detailed data on ADI underwriting policies and key risk indicators, to identify outliers;

- written to boards of the larger lenders, seeking their written assurances with respect to their oversight of the evolving risks in residential mortgage lending;

- issued a prudential practice guide (APG 223) on sound risk management practices for residential mortgage lending; and

- completed a stress test of the largest ADIs, with two scenarios focussed on a severe downturn in the housing market.

Not all of you have been directly involved with every one of these initiatives, but I’m sure you will have felt APRA’s presence in some shape or form.

We see this increasing intensity as an example of APRA’s risk-based approach to supervision. As housing-related risks have potentially grown, we have sought to ‘turn up the dial’ of our supervisory scrutiny and, importantly, ensure that Boards and management of ADIs are doing likewise.

Our most recent turning up of the dial was the letter sent to all ADIs in December last year regarding our plans to reinforce sound lending standards2. The letter, beyond expressing some of the general concerns I have just touched upon, also set out some more specific areas that APRA supervisors would be focussing on, and how we would respond if we felt our concerns were not being addressed. Similar sentiments have also been included in more recent letters sent to smaller ADIs.

There are a number of additional regulatory and supervisory tools that APRA has available to address emerging risks: additional supervisory monitoring and oversight, supervisory actions involving Pillar 2 capital requirements for individual ADIs, and higher regulatory capital requirements at a system-wide level. Beyond this, there are more direct controls that are increasingly being used in other jurisdictions, such as limits on particular types of lending – what are commonly referred to as macro-prudential controls.

Up to this point, we have opted to stick with traditional micro-prudential tools targeted at individual ADIs and their specific practices, albeit with an eye to financial stability risks as well as the safety and soundness of individual entities. We are not seeking to determine an appropriate level of house prices, or a particular level of household debt. That is beyond our mandate. Our goal is simpler: reinforcing sound lending standards, which is the ‘bread and butter’ work of a banking supervisor.

Accurately assessing a borrower’s ability to service and ultimately to repay a loan without undue hardship, including under periods of economic stress, is an inherent component of sound credit risk management, particularly for residential mortgage lending.3

One of the interesting challenges of assessing serviceability practices has been that, just as the vast majority of motor vehicle drivers believe they are above average in driving ability, ADIs invariably claim their lending standards are at the more conservative end of the spectrum, and that it is their competitors that are the source of poor practices. As with everyone claiming to be an above-average driver, not every ADI can be right.

To help us get to the bottom of this, we recently undertook a small hypothetical borrower survey. We asked a number of the larger housing lenders (including a few mutuals) to provide their serviceability assessments for four hypothetical borrowers that we invented (two owner-occupiers, and two investors). The outcomes for these hypothetical borrowers helped to put the spotlight on differences in credit assessments and lending standards. The outcomes were quite enlightening for us – and, to be frank, a little disconcerting in places.

Mortgage lending is often thought of as a fairly commoditised product, but in reality there are wide differences in how lenders assessed the risk of a given borrower. The first surprising result from our review was the very wide range of loan amounts that, hypothetically, were offered to our borrowers. It was not uncommon to find the most generous ADI was prepared to lend in the order of 50 per cent more than the most conservative ADI.

More importantly, the exercise also allowed us to explore the key drivers of difference in risk assessments across lenders. Serviceability is obviously multi-dimensional; it depends on how big a loan is extended, relative to a borrower’s income (and the reliability of the various components of that income) and the nature and extent of non-housing obligations that a borrower needs to meet.

One significant factor behind differences in serviceability assessments, particularly for owner occupiers, was how ADIs measured the borrower’s living expenses (Chart 2a and 2b). As a regulator, it is hard to understand the rationale for large differences in what should be a relatively objective, and extremely critical, metric.4

Of major concern were a few ADIs who opted to make their credit assessment based on a lower level of living expenses than that declared by the borrower. That is obviously a practice that should not continue, and ADIs should be making reasonable inquiries about a borrower’s living expenses. In fact, best practice (and intuition) would be to apply minimum living expense assumptions that increase with borrower incomes; this was a practice adopted by only a minority of ADIs in our survey.

The treatment of other income sources (such as bonuses, overtime and investment earnings) also played a large role in credit decisions (Chart 3). Common sense would suggest it is prudent to apply a discount or haircut to these types of income, reflecting the fact they are often less reliable means of meeting regular loan repayments. Unfortunately, common sense was sometimes absent.

Another area of interest was the discount or ‘haircut’ applied to declared rental income on an investment property. The norm in the ADI industry seems to be a 20% haircut, but we noted in our exercise that some ADIs based their serviceability assessment on smaller, or even zero, haircuts. Bearing in mind that the cost of real estate fees, strata fees, rates and maintenance can easily account for a significant part of expected rental income, and this does not take into account potential periods of vacancy, the 20% norm itself does not seem particularly conservative. We also came across a few instances in which ADIs were relying on anticipated future tax benefits from negative gearing to get a borrower over the line for a mortgage.

Variations in assessments were also driven by the size of interest-rate buffers applied to the new loan (Chart 4) – something we flagged in our December letter as an area of particular importance. For investor lending, this issue was more pronounced: a major driver of differences across ADIs was whether an interest-rate buffer was applied to both the investor’s existing debts (such as loans outstanding on existing owner-occupied or investment properties), as well as to the proposed new loan. As of earlier this year when the survey was conducted, only about half of the surveyed ADIs applied such a buffer to existing debts (all applied some form of buffer to new debts). I confess to struggling to see the logic of such an approach – after all, any rise in interest rates will at some point in time affect the borrower’s other debts just as they will for the new loan being sought.

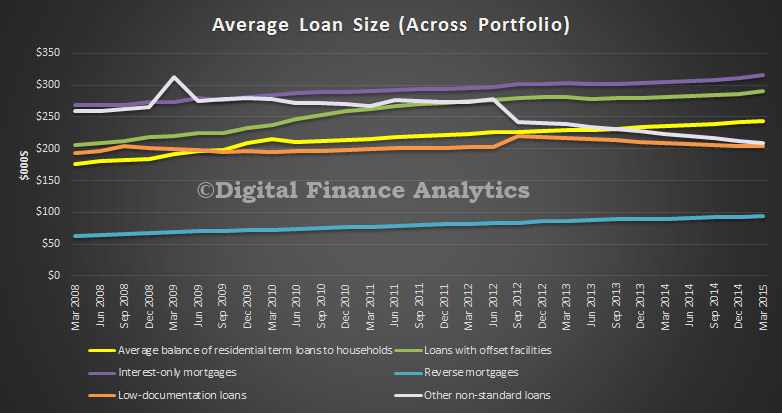

The final area I would highlight were differences in the treatment of interest only loans. Our test included one borrower seeking a 30-year loan, with the first 5 years on an interest-only basis. Only a minority of surveyed ADIs calculated the ability to service principal and interest (P&I) repayments over the residual 25 year term. Despite the contractual terms, the majority assumed P&I repayments over the full 30-year term, and hence were able to inflate the hypothetical borrower’s apparent surplus income by, in our particular example, around 5 per cent.

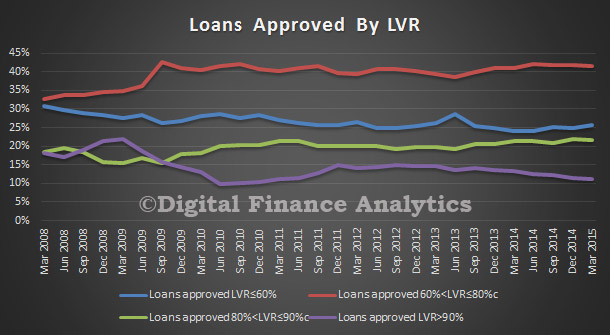

So there is no confusion, let me be clear that Australian ADIs are thankfully well away from the types of subprime lending that have caused so many problems elsewhere (eg lending with an LVR in excess of 100 per cent, at teaser rates, to borrowers with no real capacity to repay). Nevertheless, our overall conclusion from this hypothetical borrower exercise was that there were clearly examples of practice that were less than prudent. As a result, we have shown ADIs that participated in the exercise how they compare to their peers and where their serviceability assessments could be strengthened: in all of the examples above, we expect to see changes to practices across a range of ADIs.

In doing so, we have been asked whether APRA is trying to standardise mortgage risk assessments or impose a common ‘risk appetite’ across the industry. In fact, we do think it important that ADIs adhere to some minimum expectations with respect to, for example, interest-rate buffers and floors, and adopt prudent estimates of borrower’s likely income and expenses. In that regard, to the extent we are reinforcing a healthy dose of common sense in lending standards, greater convergence is probably warranted.

At the same time, we certainly want to see competition between lenders and fully accept that different ADIs can have different risk appetites. And we are not seeking to interfere in ADIs’ ability to compete on price, service standards or other aspects of the customer experience. However, making overly optimistic assessments of a borrower’s capacity to repay does not seem a sensible or sustainable basis on which to attract new customers or retain existing ones. It also runs the risk of adverse selection and an accumulation of higher risk customers who (perhaps quite justifiably) cannot get finance elsewhere. To go back to my opening remarks, it does not fulfil the precondition for long-term success.

I have mentioned all of this for two reasons:

- First, because what at first glance might seem prudent practice is not always so. When our December letter was issued, a number of ADIs were quick to point out they were already utilising a floor rate of 7 per cent and a buffer of 2 per cent within their serviceability assessments. Leaving aside that our letter suggested it would be good practice to operate comfortably above those levels, if the buffers are being applied to overly optimistic assessments of income, or only to part of the borrower’s debts, they do not serve their purpose.

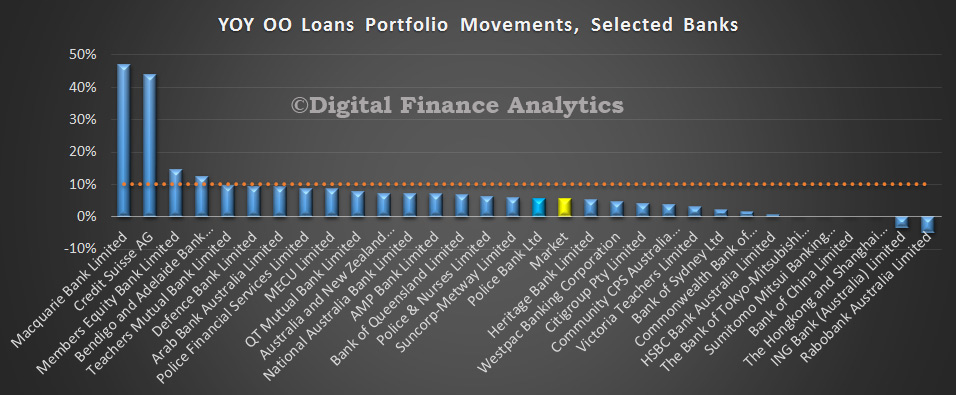

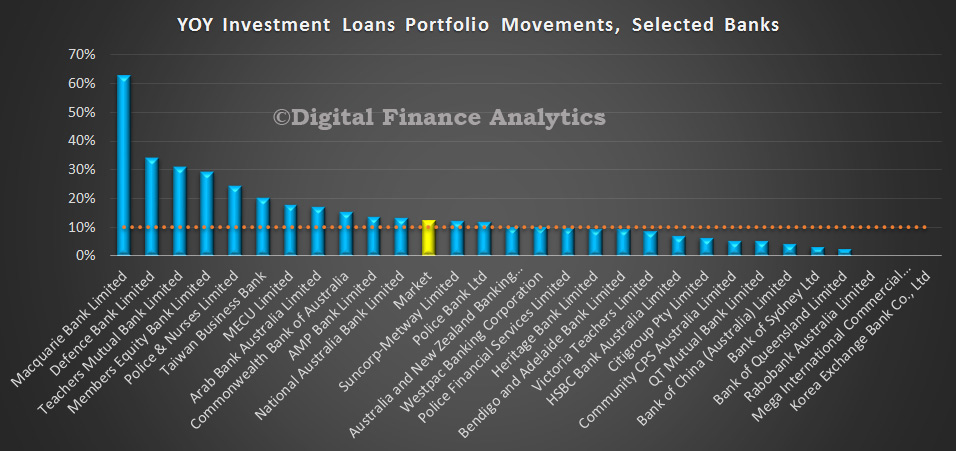

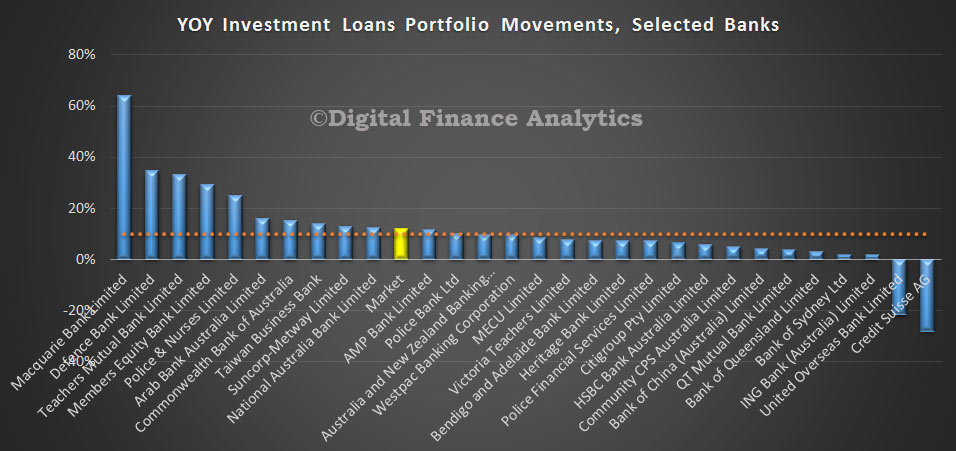

- Second, because much of the attention given to our December letter has focussed on the 10 per cent benchmark for growth in investor lending. I want to emphasise that our analysis goes much broader than just investor lending growth, and captures ADIs’ lending standards and risk profile across the board. Investor lending aspirations will only be one factor in our consideration of the need for further supervisory action.

This work on lending standards has been intensive and time-consuming for APRA and, no doubt, all of the ADIs involved, but has been well worth it if we have been able to reinforce sound lending standards across the industry. (If you have not yet looked at your own policies in the areas I have outlined, I would encourage you to do so as a matter of priority.) Of course, we will need to keep up our scrutiny and be alert to both subsequent policy changes, and/or substantial policy overrides (ie loan approvals outside policy). The latter will warrant particular attention by both ADIs and APRA: if policies are tightened only for overrides to correspondingly increase, we will have not achieved our objective.

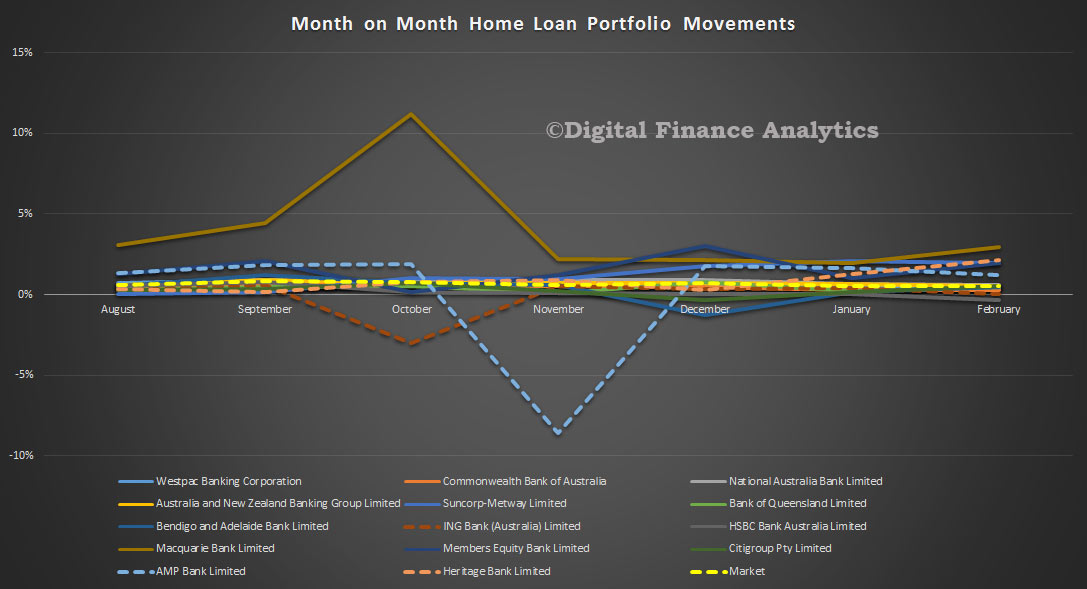

That also applies to business plans and growth aspirations: where we have agreed plans with ADIs, we will obviously be monitoring closely to see that they kick into effect in the second half of the year. We recognise that it takes time for growth plans to alter course, especially given lending pipelines of pre-approved loans (there is also typically slightly stronger growth in the second quarter of the calendar year). However, ADIs have now had long enough to revise their ambitions where needed, and we will be watching carefully to see a moderation in growth in investor lending in the second half of the year as revised plans are implemented.

Let me now turn to capital adequacy.

As most of you know, there were five recommendations from the Final Report of the Financial System Inquiry that relate to ADI capital:

- Recommendation 1 – that we set ADI capital standards in such a manner as to ensure ADIs are ‘unquestionably strong’ (with a suggestion this could be met by having Australian banks in the top quartile when measured against the capital ratios of international peers);

- Recommendation 2 – that we narrow the differential in risk weights on mortgages between the standardised and internal-ratings based (IRB) approaches (again, with a suggestion of a 25-30 per cent risk weight for the IRB approach);

- Recommendation 3 – that we should implement a framework for additional loss absorbing and recapitalisation capacity in line with international practice;

- Recommendation 4 – that we develop a reporting template that allows the capital ratios of Australian ADIs to be reported without the impact of APRA adjustments to the Basel minimums; and

- Recommendation 8 – that we introduce a leverage ratio as a backstop to the risk-based capital framework.

In addition, the Basel Committee has work underway that will intersect with these recommendations. Most relevantly, it is currently considering:

- responses to submissions on proposed revisions to the standardised approach, including, importantly, to housing risk weights;

- responses to submissions on proposed revisions to the capital floor for banks using the IRB approach; and

- how the IRB framework can be reinforced, given the increasing scepticism towards modelling approaches in light of the excessive variability in capital requirements they are producing.

To repeat what I have said previously, it is to everyone’s benefit that we approach the FSI and Basel proposals in a coordinated manner. But that does not mean waiting until every i is dotted and t is crossed.

The Basel Committee meets again in June to review the way ahead on its various proposals. I do not think it will be too long after that that we are able to announce how we will respond to those issues that are easiest to tackle sooner rather than later (particularly Recommendations 2 and 4). Other items will take a little longer to pin down the precise detail. But the direction is clear, and we fully support the FSI’s recommendation that Australian ADIs should be unquestionably strong. So it also makes sense to start early and move forward in an orderly fashion wherever possible: affected ADIs should, provided they take sensible opportunities to accumulate capital, be well-placed to accommodate these changes when they occur.

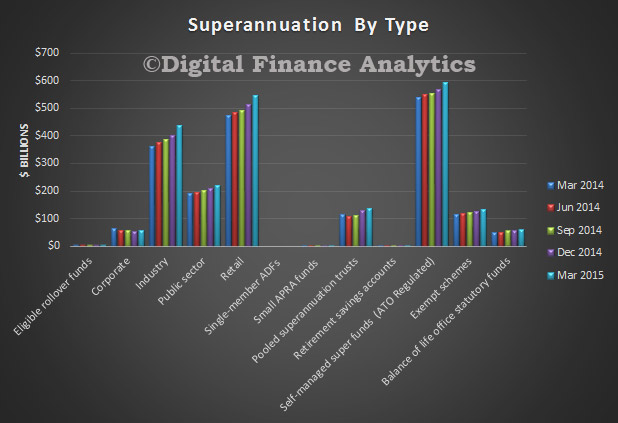

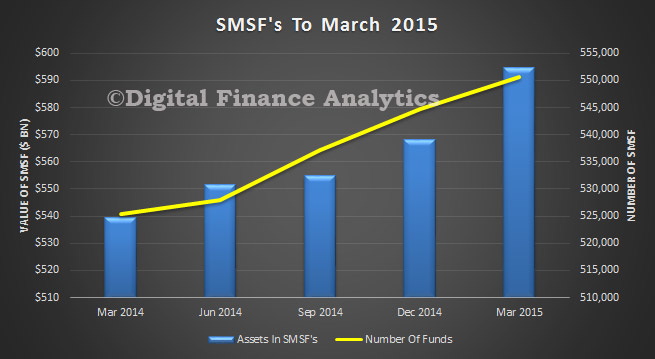

What does all of it mean for customer-owned banking organisations? As this audience already knows, the capital ratios of credit unions and building societies stand, on average, well above that of the rest of the banking sector (Chart 5), providing a healthy buffer with which to accommodate any future changes. I suspect that, when looked at in aggregate, mutual ADIs will be less impacted by the collective set of changes to regulatory requirements than other parts of the ADI sector. Of course, within the sector, there are differences from ADI to ADI, so I am wary of making sweeping statements. But there is no doubt that mutual ADIs generally start with high capital ratios vis-à-vis many of their larger competitors, and the impact of changes are likely to be felt more acutely elsewhere.

That said – and I wouldn’t be true to my role as a prudential supervisor if I did not sound a note of caution before I conclude – it doesn’t mean the changes won’t be felt at all, or that changes in the competitive landscape will provide a panacea to the strategic challenges that face smaller organisations in a more demanding environment. Long-standing issues of scale, geographic concentration, technological capacity, and more mobile and demanding customers will not be diminished by regulatory changes. The only suggestion I would offer on these today is that the challenges will be more likely to be overcome if, consistent with the mutual ethos that underpins COBA and its members, the mutual sector works cooperatively together to address them.

I opened by setting out two necessary – but not sufficient – preconditions for long-term success: sound lending standards and adequate capital.

Lending standards are important for the stability of the Australian banking system, and given the importance of housing-related lending, it should not be surprising that APRA supervisors are increasingly vigilant on the risks this lending presents. Put simply, if all our eggs are increasingly being placed in one basket, we need to make sure the basket isn’t dropped. ADIs that have continued to adopt sensible practices and prudent credit assessments should welcome this approach, as it strengthens their capacity to compete without being reckless. On the other hand, ADIs with more aggressive practices should fully expect to find APRA increasingly at their doorstep.

When it comes to capital, we will have more to say shortly. But my message today is that we will respond to all of the FSI’s recommendations as soon as we can, bearing in mind the need for a coordinated approach that factors in international work that is still in the pipeline. No one disputes the benefits of having an unquestionably strong banking sector, so where it makes sense to move ahead, we will get on with it. ADIs should adopt a similar approach in their capital planning: to the extent further capital accumulation is needed, there is little to be lost from starting early.

1 Seeking Strength in Adversity, AB+F Randstad Leaders Lecture Series, 7 November 2014

2 Reinforcing Sound Residential Mortgage Lending Practices, 9 December 2014

3 APG223, Residential Mortgage Lending, November 2014. See also Financial Stability Board, Sound Residential Mortgage Underwriting Practices, April 2012.

4 Estimated living expenses between the most conservative and the least conservative ADI varied by at least 30 per cent, and in some cases significantly more (depending on the borrower’s characteristics).

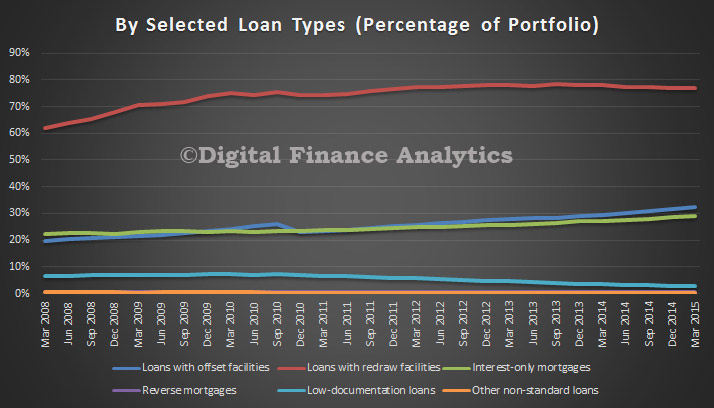

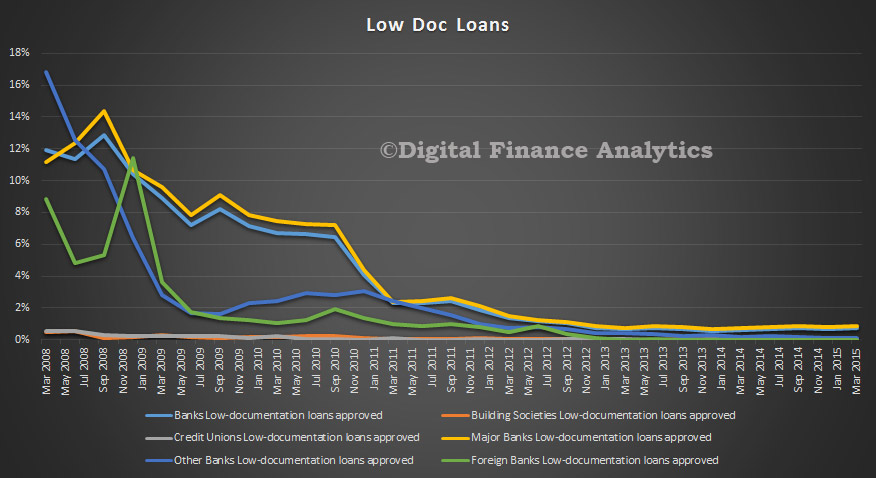

The proportion of low doc loans written is miniscule and now consistently low. Most low doc borrowers would now be knocking on the door of the non-ADI’s as they do not have the same heavy supervisory oversight and are tending to be more flexible – but there is little public data on this.

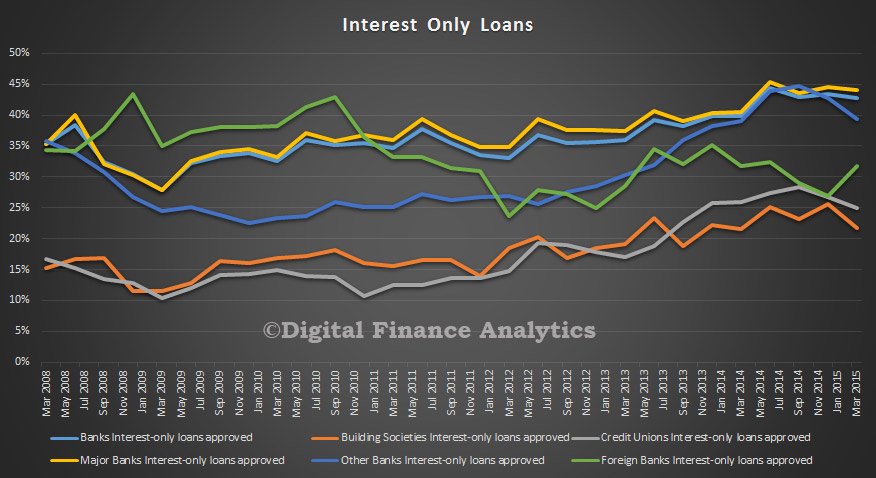

The proportion of low doc loans written is miniscule and now consistently low. Most low doc borrowers would now be knocking on the door of the non-ADI’s as they do not have the same heavy supervisory oversight and are tending to be more flexible – but there is little public data on this. Turning to interest only loans, the Majors, and Other Banks are most likely to write this type of loan. However, we note the rising proportion of Credit Unions, Building Societies and Foreign Banks who will consider the proposition.

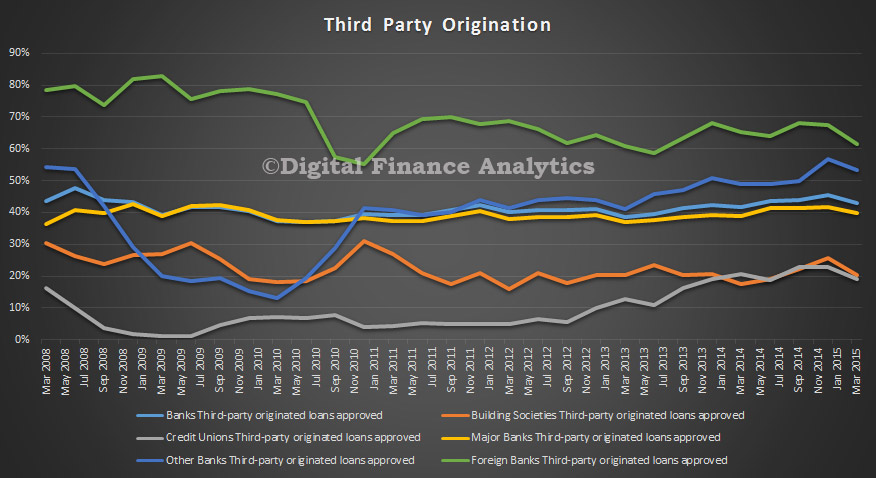

Turning to interest only loans, the Majors, and Other Banks are most likely to write this type of loan. However, we note the rising proportion of Credit Unions, Building Societies and Foreign Banks who will consider the proposition. Finally, looking at the use of the broker channel, Foregin Banks originate the highest proportion this way, with the smaller Banks also in on the third party origination game. Credit Unions and Building Societies are less inclined to use Brokers, though there have been some increase in recent years.

Finally, looking at the use of the broker channel, Foregin Banks originate the highest proportion this way, with the smaller Banks also in on the third party origination game. Credit Unions and Building Societies are less inclined to use Brokers, though there have been some increase in recent years.