The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has today written to authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) outlining further steps it plans to take to reinforce sound residential mortgage lending practices. These steps have been developed following discussions with other members of the Council of Financial Regulators.

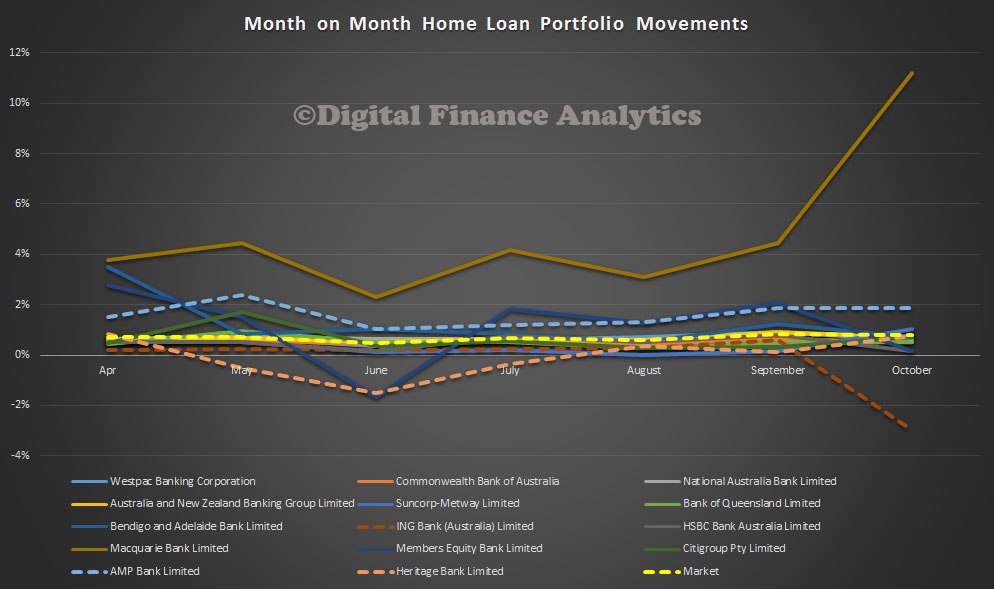

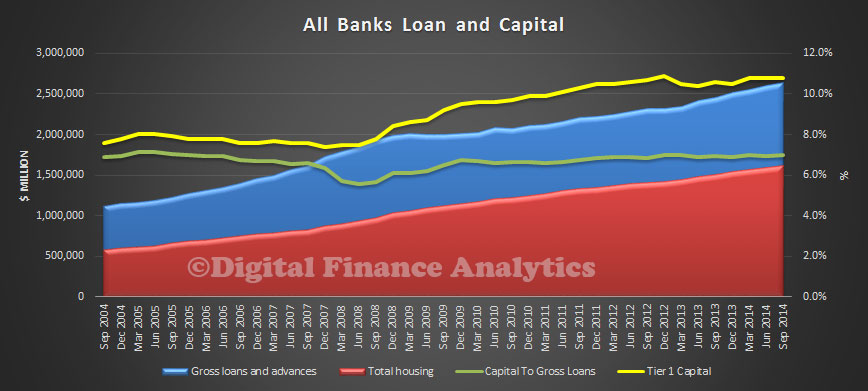

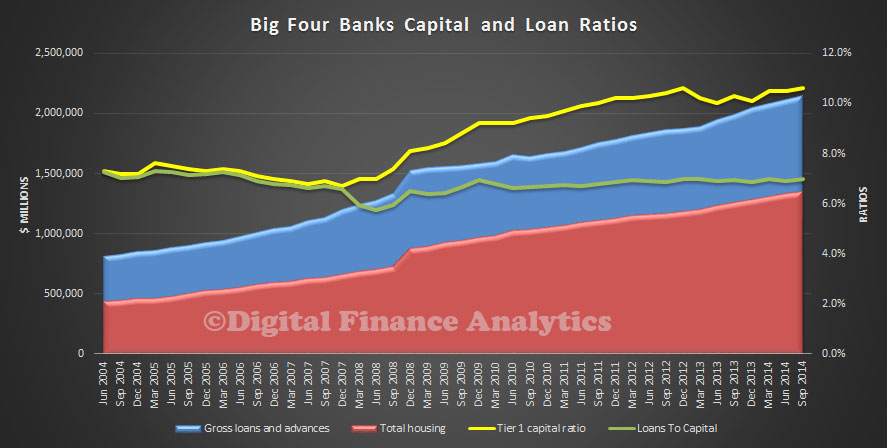

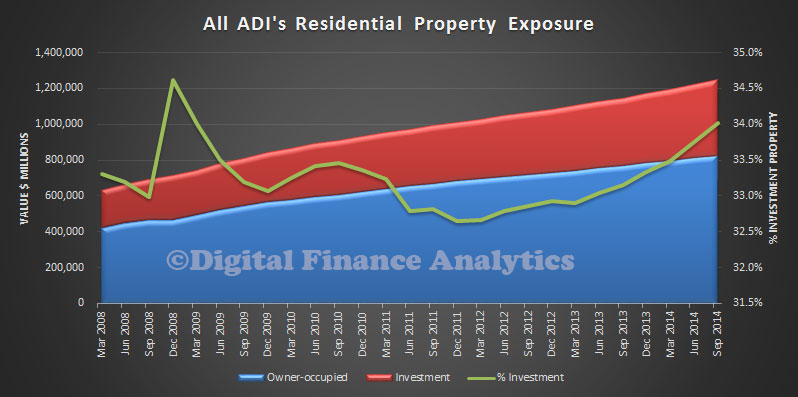

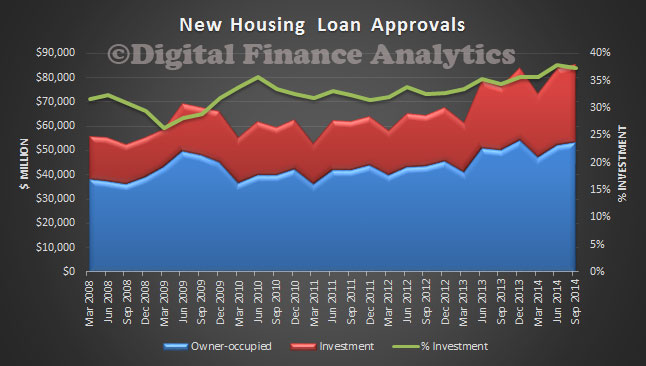

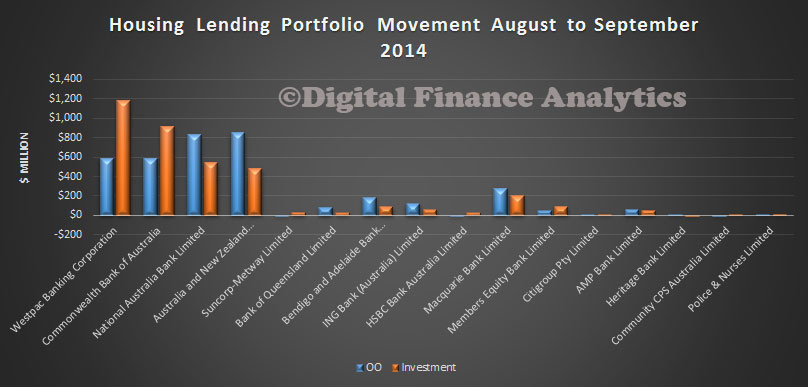

In the context of historically low interest rates, high levels of household debt, strong competition in the housing market and accelerating credit growth, APRA has indicated it will be further increasing the level of supervisory oversight on mortgage lending in the period ahead.

At this point in time, APRA does not propose to introduce across-the-board increases in capital requirements, or caps on particular types of loans, to address current risks in the housing sector. However, APRA has flagged to ADIs that it will be paying particular attention to specific areas of prudential concern. These include:

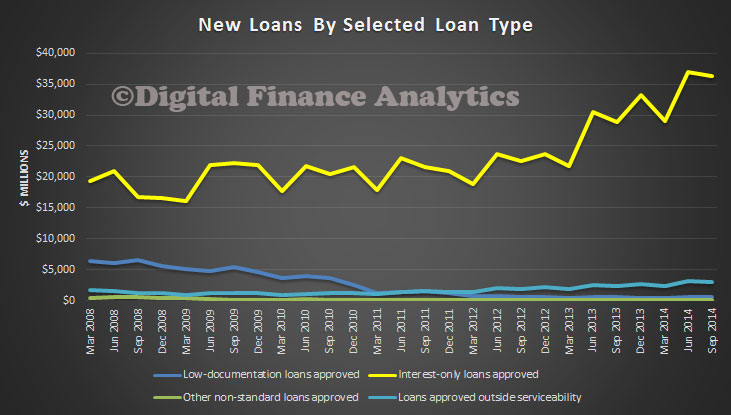

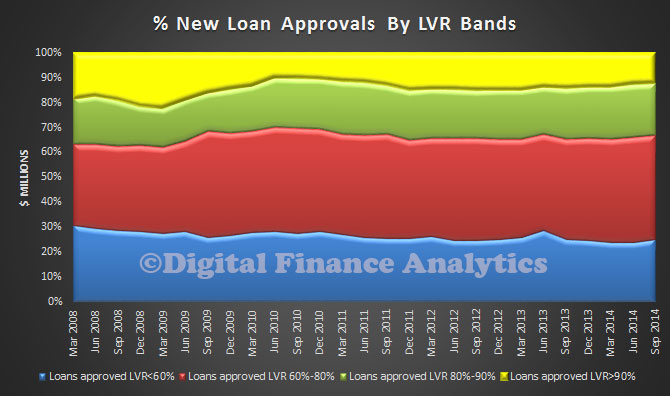

- higher risk mortgage lending — for example, high loan-to-income loans, high loan-to-valuation (LVR) loans, interest-only loans to owner occupiers, and loans with very long terms;

- strong growth in lending to property investors — portfolio growth materially above a threshold of 10 per cent will be an important risk indicator for APRA supervisors in considering the need for further action;

- loan affordability tests for new borrowers — in APRA’s view, these should incorporate an interest rate buffer of at least 2 per cent above the loan product rate, and a floor lending rate of at least 7 per cent, when assessing borrowers’ ability to service their loans. Good practice would be to maintain a buffer and floor rate comfortably above these levels.

In the first quarter of 2015, APRA supervisors will be reviewing ADIs’ lending practices and, where an ADI is not maintaining a prudent approach, may institute further supervisory action. This could include increases in the level of capital that those individual ADIs are required to hold.

APRA Chairman Wayne Byres noted that while in many cases ADIs already operate in line with these expectations, the steps announced today will help guard against a relaxation of lending standards and, where relevant, prompt some ADIs to adopt a more prudent approach in the current environment.

‘This is a measured and targeted response to emerging pressures in the housing market. These steps represent a dialling up in the intensity of APRA’s supervision, proportionate to the current level of risk and targeted at specific higher risk lending practices in individual ADIs’ he said.

‘There are other steps open to APRA, should risks intensify or lending standards weaken and, in conjunction with other members of the Council of Financial Regulators, we will continue to keep these under active review.’

The steps announced today build on the enhanced monitoring and supervisory oversight of residential mortgage lending risks that APRA has put in place over the past year, which has included a major stress test of the banking industry, targeted reviews of ADIs’ residential mortgage lending and the release of detailed guidance to ADIs on sound residential mortgage lending practices.

APRA’s heightened supervisory focus on lending standards will be conducted in conjunction with the review of interest-only lending announced today by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). APRA and other members of the Council of Financial Regulators will continue to work closely together to monitor, assess and respond to risks in the housing market as they develop.

Today’s letter to ADIs can be found on the APRA website here: www.apra.gov.au/adi/Publications/Pages/other-information-for-adis.aspx

BACKGROUND

Q: What impact does APRA expect this announcement to have?

A: The aim of this announcement is to further reinforce sound residential mortgage lending practices in the context of historically low interest rates, high levels of household debt, strong competition in the housing market and accelerating housing credit growth. We expect this announcement will help guard against any relaxation of lending standards, and also prompt some ADIs to reinforce their lending practices where there is scope for a more prudent approach in the current risk environment.

Q: What ‘higher risk lending’ practices will APRA be focussing on?

A: APRA will be focussing on the extent to which ADIs are lending at high multiples of borrower’s income, lending at high loan-to-valuation ratios, lending on an interest-only basis to owner-occupiers for lengthy periods and lending for very long terms.

Q: How was the 10 per cent threshold for investor lending determined?

A: The 10 per cent benchmark is not a hard limit, but is a key risk indicator for supervisors in the current environment. The benchmark has been established after advice from members of the Council of Financial Regulators, taking into account a range of factors including income growth and recent market trends.

Q: How was the 2 per cent buffer and 7 per cent floor lending rate determined?

A: The guidance on serviceability assessments was based on a number of considerations, including past increases in lending rates in Australia and other jurisdictions, market forecasts for interest rates, international benchmarks for serviceability buffers, and long-run average lending rates.

Q: Is the 10 per cent growth in investor lending, or the 2 per cent buffer, a hard limit?

A: No. These figures are intended to be trigger points for more intense supervisory action. Where banks are achieving materially faster growth, utilising a lower buffer, and/or otherwise materially growing the other higher risk parts of their portfolio, it will be a trigger for supervisors to consider whether more intensive supervisory action, including higher capital requirements, may be warranted.

Q: What sort of supervisory action might be considered if banks exceed these thresholds?

A: There are a range of actions that APRA can take, depending on the circumstances. These could include some or all of increased reporting obligations, additional on-site reviews, mandated reviews by external parties, and higher capital requirements.

Q: How may this affect borrowers from obtaining home loans from ADIs?

A: APRA does not expect this to have any effect on the availability of credit for people borrowing within their means to purchase a home. ADIs already conduct affordability tests to ensure that new borrowers are not overstretching themselves to purchase property, or relying on expectations of future increases in house prices to afford to do so. This guidance will primarily guard against any further relaxation in standards.

Q. Why has APRA not introduced high LVR or serviceability limits, as in other countries?

A: In short, we do not see those sorts of limits as necessary or appropriate at this stage. APRA’s response has been targeted on the specific areas of prudential concern in the current environment: these include risks around serviceability when interest rates are at historically low levels, strong investor loan growth and broader considerations of each ADI’s risk profile. The impact of any APRA actions will therefore be felt by those banks pursing higher risk lending strategies and/or using lower loan underwriting standards.

There is, of course, a range of further actions that could be taken in relation to residential mortgage lending practices if the risk outlook intensifies, and APRA will continue to keep these under review as market conditions and lending standards evolve.

Q: What role did the Council of Financial Regulators play in the decision-making?

A: Given that these supervisory tools sit within APRA’s supervisory and regulatory framework, APRA is ultimately responsible for determining the appropriate supervisory response. However, we have taken advice from other members of the Council of Financial Regulators in developing our approach, and will continue to do so. ASIC has also today announced a review that it will be carrying out a review of interest-only lending, which will support APRA’s efforts to reinforce sound lending practices.

Q: Why is there a threshold for growth in investor lending, not total housing credit?

A: There is currently very strong growth in lending to property investors, as highlighted by the Reserve Bank in its most recent Financial Stability Review (FSR). This is leading to imbalances in the housing market; the RBA noted in the FSR that “the direct risks to financial institutions would increase if these high rates of lending growth persist, or increase further.” APRA’s approach has therefore sought to target the higher areas of risk.

Q: Does this relate to the recommendation on risk weights in the Financial System Inquiry report?

A: No. The recommendation on risk weights in the FSI report is focused on competitive issues with risk modelling, whereas the announcement today is in relation to further supervisory steps to address specific risks in residential mortgage lending.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the Australian financial services industry. It oversees Australia’s banks, credit unions, building societies, life and general insurance companies and reinsurance companies, friendly societies and most of the superannuation industry. APRA is funded largely by the industries that it supervises. It was established on 1 July 1998. APRA currently supervises institutions holding $4.9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.