In a speech to TheCityUK Jon Cunliffe charts the development of macroprudential policy and the establishment of the macroprudential policy framework in the UK by the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee (FPC) since the Committee’s inception in 2011. He also looks ahead at some of the policy questions facing the FPC.

A key outcome of the financial crisis was the recognition that international standards were needed not just to ensure that individual banks were safe but also to ensure that the financial system as a whole was safe. The crisis showed that there are powerful dynamics in the financial system itself which drive booms in good times and busts in bad times. Seven years on from the crisis and four years from the establishment of the FPC, Jon says it is fair to ask how well regulators have done in putting in place the machinery to manage those risks and whether these have come at the expense of economic growth.

The contours of the new regulatory framework are clear and agreed and implementation is well underway, Jon notes, citing rules on bank capital and liquidity, resolution and work on addressing risks from outside the banking system, for instance from derivatives.

But he argues that this “standing framework” can only go so far in addressing risk. The role of macro-prudential authorities like the FPC is not just to ensure that regulations address the risk that financial firms and banks can pose to the financial system as a whole. It is also to monitor the build-up of risk and the development of new types of risk and to take action to address them.

In this area, macroprudential policy is at a much earlier stage of development, partly because the focus has so far been on creating the framework for policy, partly because there are still differing views internationally as to what time-varying, countercyclical macroprudential policy should and could do. Nonetheless, the FPC has taken some important steps here.

First, using macroprudential policy to address changing risks depends upon a clear assessment of risks and of the action necessary to address them. This is why the FPC has changed the structure and content of the Financial Stability Report. “The intention is that such a shorter, more focussed report will create a discipline for the FPC’s thinking, aid its communication and make it easier for others to hold us to account.”

Second, the Committee is developing the use of stress testing to assess macroprudential as well as microprudential risk. “At present we are using stress testing to help us judge how resilient the banking system is to different, severely adverse, but plausible, scenarios. A development of this approach would be to use stress testing more countercyclically. Rather than testing every year against a scenario of constant severity, the severity of

the test and the resilience banks need to pass it would be greater in boom times when credit and risk is building up in the financial system and it has further to fall, and then reduced in weaker periods when there is less risk in the system and the economy needs the banking system to maintain lending.”

Thirdly, the FPC has been looking at macroprudential risks beyond the banking system. Its recommendation on portfolio limits for high loan-to-income mortgages is an example of the committee taking a broad view of financial stability that goes wider than direct risks to the banking system.

On the question of whether financial regulation has gone too far, Jon says only now that reforms are being implemented is it possible for policymakers to see the whole picture of how they work together in practice and that some adjustments will be needed. “Given the depth and complexity of the financial crisis and the corresponding depth and complexity of the reforms, we should expect rather than be surprised that we will need to refine and adjust some of the regulatory reforms.”

However, while some adjustments may be necessary as we see how the reforms work in practice, Jon warns against seeking more generally to trade-off between financial stability and growth and notes that the post-crisis world requires a major adjustment in bank business models.

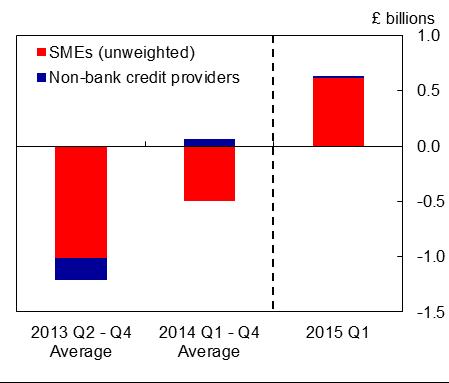

Jon also points out that in the long build-up of the credit cycle ahead of the crisis, while lending nearly doubled this did not lead to a very large increase in the financing of companies. Instead, lending was mainly directed to other financial institutions, mortgages and real estate.

“While we have relearned some familiar lessons in recent years, we have also learned some new ones. We have had to develop a new regulatory framework, macroprudential institutions like the FPC, and new policy approaches. Over the next few years we will certainly need to refine all of these. The implementation of the detailed reforms will inevitably throw up unforeseen effects in particular places, and where it is justified, we

will need to revisit issues. But we should be careful about talking about turning back the overall regulatory dial or trying to trade off the risk of financial instability for short-term growth.”