The Bank of England just published an interesting report on household finances. There are some interesting parallels with Australia.

Tag: Bank of England

The Next Bank of England Governor Must Take A Radically Different Approach

Following the monumental Conservative election victory, now is the time for the economics to work through. Mark Carney is due to leave his post as governor of the Bank of England at the end of January after six and a half years in charge, and the chancellor, Sajid Javid, will be choosing a replacement soon – perhaps before Christmas. Via the UK Conversation.

This will be a pivotal decision for the chancellor – no doubt in close consultation with Boris Johnson and his advisers. Whoever they pick should not expect a honeymoon period. They are arriving against the backdrop of Brexit, widening regional inequality and the prospect of a downturn in the global economy.

The frontrunners are said to be Minouche Shafik, director of London School of Economics; Kevin Warsh, a former top official at the US Federal Reserve; and Andrew Bailey, chief executive of UK regulator the Financial Conduct Authority. Add to these names Jon Cunliffe and Ben Broadbent, both currently deputy governors at the Bank. Behind this sits a couple of more alternative candidates: Santander chair and former Labour minister Shriti Vadera and Boris Johnson’s former economic adviser, Gerard Lyons.

An alternative governor may be just the required medicine at present, since there is a strong case for someone willing to think differently about central bank management. With interest rates still very low in the UK and most other developed economies, there are widespread concerns that central banks will be unable to fight another downturn using the classic response of cutting rates.

Beyond this, there are arguments for revising the entire model of central banking. In recent years, the trend has been for them to manage rates without any political interference and to concentrate purely on keeping inflation low. Indeed, it is almost 30 years to the day since the Reserve Bank of New Zealand became the first central bank to make inflation the sole priority.

In times of inflation, this system made sense. But since the 2007-08 financial crisis, the world has found itself in a situation where economic growth is much weaker and deflation is more of a risk than inflation.

The Bernanke exception

As former Federal Reserve chair Ben Bernanke said in a speech in Tokyo in 2003, “in the face of inflation … the virtue of an independent central bank is its ability to say ‘no’ to the government”, but with protracted deflation of the kind that has continually dogged Japan, “a more cooperative stance” by central banks towards the government is required.

His argument was essentially that it’s hard to sustain inflation by manipulating interest rates, and that you’re more likely to be successful using the fiscal levers of government spending and tax cutting. The same approach is arguably required in the UK today and across the developed world.

Having lost the ability to properly stimulate the economy using interest rates, the Bank of England and other central banks have taken it in turns to resort to quantitative easing – essentially creating money with which to buy mainly government bonds from banks and other financial institutions. This was supposed to drive extra liquidity into the economy, but mainly it has just been used to bid up prices in the likes of the bond market and stock market and exacerbate the wealth gap.

As an alternative, some commentators are now touting “helicopter money”: this would involve central banks creating money that would be handed straight to the public via government tax cuts or public spending – thus requiring them to coordinate their policies in a way that does not happen at present.

This could be pursued in conjunction with a novel concept called “modern monetary theory”, which envisages government targets to boost demand and inflation financed by a disciplined central bank that keeps interest rates at zero. We are already seeing signs of the government moving in the same direction by shifting away from austerity towards more generous spending.

As for the Bank of England’s own targets, greater policy cooperation with the government would provide wiggle room for focusing beyond inflation. In particular, the Bank could play a role in addressing regional inequality. The UK already has the one of the worst rates of regional inequality in the developed world, with areas like the north of England and West Midlands bringing up the rear. This will be heightened by leaving the EU, since these same areas are key to international supply chains and expected to be the worst hit.

The answer is for the government to pursue an industrial policy that aims to improve productivity in regions where it is weakest, through the likes of targeted tax breaks and economic development zones, with an accommodating Bank of England providing the funding to facilitate.

More productive areas attract more capital, which is the reason behind the north-south divide in the first place. Such an industrial policy would encourage more investment in these areas, produce real-wage increases, boost local demand and stimulate regional development. In short, it would help counteract the impact of Brexit.

Long-term thinking

Two central criteria for the appointment of the next Bank of England governor stand out. First, they must understand the deeper economic and social circumstances that have led to Brexit and the UK’s shift to the right. They must act as governor for the whole country and not just for London plc: a move away from focusing on smoothing short-term fluctuations towards prioritising long-term growth.

Second, the job specification for the next governor says that the candidate should have “acute political sensitivity and awareness”. This might suggest that the government does not want another governor with such outspoken views on say, the economic risks from Brexit. Be that as it may, policy coordination needs to be a priority. I don’t rule out the possibility of the leading candidates being able to work like this, but I worry that they will be too orthodox for the challenge. The government should recognise the shifting sands in central bank policy and appoint someone who is willing to lead from the front.

Author: Drew Woodhouse, Lecturer in Economics, Sheffield Hallam University

The Financial Stability Implications Of Climate Change [Video]

The Bank of England released a discussion paper and scenarios for the finance sector to consider the risks of climate change (whatever the cause). They conclude that financial assets are at risk and these risks need to be recognised and accounted for.

Bank of England On Stress Testing The Financial Stability Implications Of Climate Change

According to the Bank of England, climate change creates risks to both the safety and soundness of individual firms and to the stability of the financial system. These risks are already starting to crystallise, and have the potential to increase substantially in the future. There is a pressing need for central banks, regulators and financial firms to accelerate their capacity to assess and manage these risks.

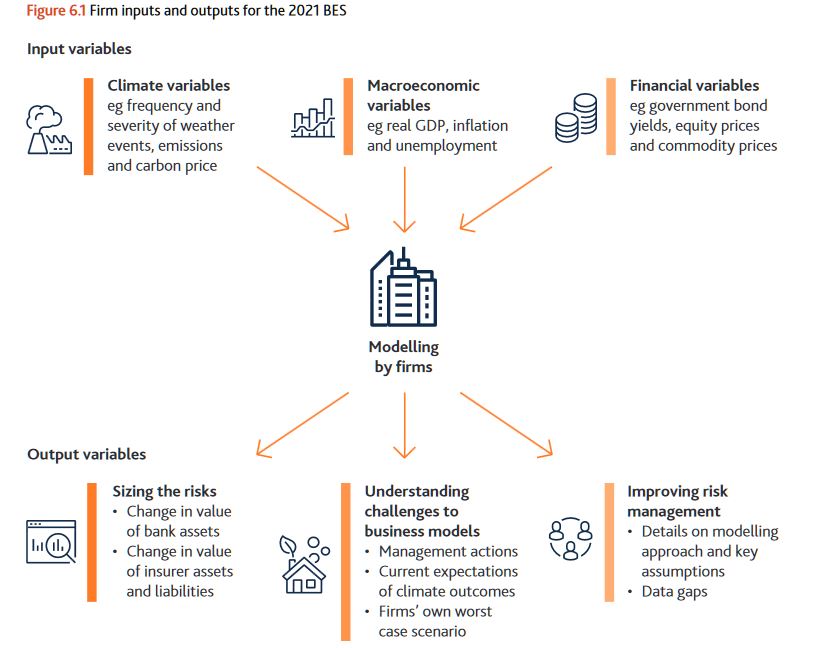

So, the Bank of England has published a discussion paper which sets out its proposed framework for the 2021 Biennial Exploratory Scenario (‘BES’) exercise.

The objective of the BES is to test the resilience of the largest banks and insurers (‘firms’) to the physical and transition risks associated with different possible climate scenarios, and the financial system’s exposure more broadly to climate-related risk.

They say, conducting a climate stress test poses distinct challenges compared to conventional macrofinancial or insurance stress tests. To ensure it is effective in light of these challenges, the Bank is using this discussion paper to consult relevant stakeholders on the design of the exercise. This includes financial firms, climate scientists, economists, other industry experts, and informed stakeholder groups.

Whilst climate-related risks will materialise over decades, actions today will affect the size of those future risks. It is therefore important that firms, and other stakeholders such as the Bank, continue to develop innovative approaches to measure climate-related risks before it is too late to ensure resilience to them. The BES will use exploratory scenarios to size these future risks and to explore how firms might respond to them materialising, rather than testing firms’ capital adequacy.

The key features of the BES are:

- Multiple Scenarios that cover climate as well as macro-variables: to test the resilience of the UK’s financial system against the physical and transition risks in three distinct climate scenarios. These range from taking early, late and no additional policy action to meet global climate goals.

- Broader participation: both banks and insurers are exposed to climate-related risks, and the action of one will spill over to affect the other. For insurers, this exercise builds on the scenarios developed for this year’s insurance stress test.

- Longer time horizon: is needed as climate-related risks crystallise over a much longer timeframe than conventional risks. The BES proposes a modelling horizon of 30 years. This is because climate change, and the policies to mitigate it, will occur over a much longer timeframe than the normal horizon for stress testing. To make these scenarios credible and tractable, the Bank proposes that the BES examine firms’ resilience using fixed balance sheets, focusing on sizing the risks and the scale of business model adjustment required to respond to these risks, rather than testing the adequacy of firms’ capital to absorb those risks.

- Counterparty-level modelling: a bottom up, granular analysis of counterparties’ business models split by geographies and sectors is proposed to accurately capture the exposure to climate-related risks.

- Output: the Bank will disclose aggregate results of the financial sector’s resilience to climate-related risk rather than individual firms.

The Governor Mark Carney said: “The BES is a pioneering exercise, which builds on the considerable progress in addressing climate related risks that has already been made by firms, central banks and regulators. Climate change will affect the value of virtually every financial asset; the BES will help ensure the core of our financial system is resilient to those changes.”

Sarah Breeden the Executive Director sponsor for climate change said “None of us can know exactly how climate change will unfold, but we do know that it will create risks to the financial system. I am excited that this ground-breaking exercise will for the first time allow us to quantify this risk and so determine the actions we need to take today if we are to minimise these future risks.”

The Bank is consulting on the design of the exercise and welcomes feedback on the feasibility and the robustness of these proposals from firms, their counterparties, climate scientists, economists and other industry experts by 18 March 2020. The final BES framework will be published in the second half of 2020 and the results of the exercise will be published in 2021.

The Banks concludes, there are many challenges involved in designing such an exercise and this proposal seeks to balance various trade-offs. These include providing a comprehensive description of the potential risks while also creating a tractable exercise for firms, and providing sufficient detail in the scenarios to allow results to be aggregated consistently while also providing scope for firms to assess the risks in a granular way.

Machine Learning On The Rise In Financial Services

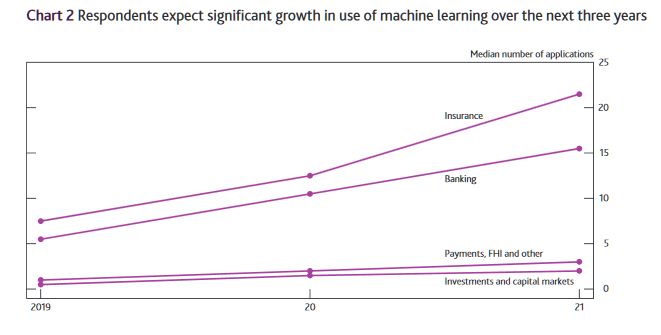

The Bank of England (BoE) and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) have a keen interest in the way that ML is being deployed by financial institutions.

They conducted a joint survey in 2019 to better understand the current use of ML in UK financial services. The survey was sent to almost 300 firms, including banks, credit brokers, e-money institutions, financial market infrastructure firms, investment managers, insurers, non-bank lenders and principal trading firms, with a total of 106 responses received.

In the financial services industry, the application of machine learning (ML) methods has the potential to improve outcomes for both businesses and consumers. In recent years, improved software and hardware as well as increasing volumes of data have accelerated the pace of ML development. The UK financial sector is beginning to take advantage of this. The promise of ML is to make financial services and markets more efficient, accessible and tailored to consumer needs. At the same time, existing risks may be amplified if governance and controls do not keep pace with technological developments. More broadly, ML also raises profound questions around the use of data, complexity of techniques and the automation of processes, systems and decision-making.

The survey asked about the nature of deployment of ML, the business areas where it is used and the maturity of applications. It also collected information on the technical characteristics of specific ML use cases. Those included how the models were tested and validated, the safeguards built into the software, the types of data and methods used, as well as considerations around benefits, risks, complexity and governance.

Although the survey findings cannot be considered to be statistically representative of the entire UK financial system, they do provide interesting insights.

The key findings of the survey are:

- ML is increasingly being used in UK financial services. Two thirds of respondents report they already use it in some form. The median firm uses live ML applications in two business areas and this is expected to more than double within the next three years.

- In many cases, ML development has passed the initial development phase, and is entering more advanced stages of deployment. One third of ML applications are used for a considerable share of activities in a specific business area. Deployment is most advanced in the banking and insurance sectors.

- From front-office to back-office, ML is now used across a range of business areas. ML is most commonly used in anti-money laundering (AML) and fraud detection as well as in customer-facing applications (eg customer services and marketing). Some firms also use ML in areas such as credit risk management, trade pricing and execution, as well as general insurance pricing and underwriting.

- Regulation is not seen as a barrier but some firms stress the need for additional guidance on how to interpret current regulation. Firms do not think regulation is a barrier to ML deployment. The biggest reported constraints are internal to firms, such as legacy IT systems and data limitations. However, firms stressed that additional guidance around how to interpret current regulation could serve as an enabler for ML deployment.

- Firms thought that ML does not necessarily create new risks, but could be an amplifier of existing ones. Such risks, for instance ML applications not working as intended, may occur if model validation and governance frameworks do not keep pace with technological developments.

- Firms use a variety of safeguards to manage the risks associated with ML. The most common safeguards are alert systems and so-called ‘human-in-the-loop’ mechanisms. These can be useful for flagging if the model does not work as intended (eg. in the case of model drift, which can occur as ML applications are continuously updated and make decisions that are outside their original parameters).

- Firms validate ML applications before and after deployment. The most common validation methods are outcome-focused monitoring and testing against benchmarks. However, many firms note that ML validation frameworks still need to evolve in line with the nature, scale and complexity of ML applications.

- Firms mostly design and develop ML applications in-house. However, they sometimes rely on third-party providers for the underlying platforms and infrastructure, such as cloud computing.

- The majority of users apply their existing model risk management framework to ML applications. But many highlight that these frameworks might have to evolve in line with increasing maturity and sophistication of ML techniques. This was also highlighted in the BoE’s response to the Future of Finance report. In order to foster further conversation around ML innovation, the BoE and the FCA have announced plans to establish a public-private group to explore some of the questions and technical areas covered in this report.

Bank of England’s Plans To Accelerate Digital Disruption

On 20 June, the Bank of England announced plans to facilitate the UK economy’s adoption of new technology through a more open financial infrastructure, via Moody’s. Although many of these plans would ultimately enable faster adoption of new technology with broader and cheaper access to financial services, they would likely be an overall credit negative for incumbent banks, which generate profits thanks in part to high barriers to entry and privileged access to data.

The Bank of England’s announcements include a variety of proposals including better infrastructure to improve payments, easier access to finance for small and midsize enterprises (SMEs), smoothing the transition to a lower-carbon economy, reducing the regulatory burden on the financial industry, and facilitating the adoption of cloud-based technologies to increase operational resilience.

Some of these initiatives will directly benefit incumbent banks. The introduction of a climate stress test will help banks reposition their credit portfolios in anticipation of the transition to a less carbon-intensive economy and thus avoid the credit risk in so-called stranded assets. The Bank of England will also explore ways of using machine learning and artificial intelligence to reduce the need for regulated financial firms to supply it with large amounts of data and to automate part of its own analytical work. These efforts should reduce regulatory costs for banks. And, a new policy on the use by banks of cloud technology and the automation of more post-trade processes will help firms adopt a cheaper and more robust infrastructure.

However, these benefits for banks are likely to be outweighed by the effect of proposals to further open up financial services provision in the UK and reduce barriers to entry.

In the payments system, the Bank of England notes that while payments via card systems are convenient for customers, these processes entail friction and inertia that result in costs for the real economy. For example, fees can consume between 0.5% and 2% per transaction, while the eventual transfer of funds between buyer and seller can take several days to complete (with fees and delays being typically greater for international transactions). In response, the UK government announced a review of payments systems, which will likely lead to further initiatives to further boost the ability of providers of newer and cheaper forms of direct payment to access the

wider market.

For its part, the Bank of England will continue to open up its real time gross settlement payment system to non-bank payment service providers. The central bank will also consult on whether to allow more firms beyond a small group of systemically important banks to access its balance sheet. Such moves, while apparently cautious at this stage, will intensify competition and lead to further margin pressure on incumbent UK banks. In addition, the Bank of England will explore ways to support new digital currencies such as that announced by Facebook, which are also likely to disintermediate established banks.

Meanwhile, the central bank will also promote greater competition in SME financing. Currently, the vast majority of SME lending in the UK is conducted through the largest four banking groups, and new entrants face significant barriers to entry, typically lacking the customer account data which helps banks make their credit decisions. The Bank of England suggests further promoting the existing principles of “open banking,” which allows customers to take control of their data and share them securely with alternative providers, helping SMEs create a “portable credit file.” Doing so would aim to reduce barriers to entry and stimulate competition, thus adding to margin pressure on banks.

Since the open banking initiative began in early 2018, there has been little effect on market shares in retail banking in the UK. But over time, the above measures mean that incumbent banks would likely experience margin declines in some of their traditionally more profitable activities of commercial lending.

Bank Of England Holds At 0.75%

The latest from the UK suggests inflation will fall below the 2% lower bounds as downside risks to growth build and the Brexit issue still haunts the halls. The Bank held the current rate, and will continue its market operations to stimulate the economy.

The Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) sets monetary policy to meet the 2% inflation target, and in a way that helps to sustain growth and employment. At its meeting ending on 19 June 2019, the MPC voted unanimously to maintain Bank Rate at 0.75%.

The Committee voted unanimously to maintain the stock of sterling non-financial investment-grade corporate bond purchases, financed by the issuance of central bank reserves, at £10 billion. The Committee also voted unanimously to maintain the stock of UK government bond purchases, financed by the issuance of central bank reserves, at £435 billion.

The MPC’s most recent economic projections, set out in the May Inflation Report, assumed a smooth adjustment to the average of a range of possible outcomes for the United Kingdom’s eventual trading relationship with the European Union and were conditioned on a path for Bank Rate that rose to around 1% by the end of the forecast period. In those projections, GDP growth was a little below potential during 2019 as a whole, reflecting subdued global growth and ongoing Brexit uncertainties. Growth then picked up above the subdued pace of potential supply growth, such that excess demand rose above 1% of potential output by the end of the forecast period. As excess demand emerged, domestic inflationary pressures firmed, such that CPI inflation picked up to above the 2% target in two years’ time and was still rising at the end of the three-year forecast period.

Since the Committee’s previous meeting, the near-term data have been broadly in line with the May Report, but downside risks to growth have increased. Globally, trade tensions have intensified. Domestically, the perceived likelihood of a no-deal Brexit has risen. Trade concerns have contributed to volatility in global equity prices and corporate bond spreads, as well as falls in industrial metals prices. Forward interest rates in major economies have fallen materially further. Increased Brexit uncertainties have put additional downward pressure on UK forward interest rates and led to a decline in the sterling exchange rate.

As expected, recent UK data have been volatile, in large part due to Brexit-related effects on financial markets and businesses. After growing by 0.5% in 2019 Q1, GDP is now expected to be flat in Q2. That in part reflects an unwind of the positive contribution to GDP in the first quarter from companies in the United Kingdom and the European Union building stocks significantly ahead of recent Brexit deadlines. Looking through recent volatility, underlying growth in the United Kingdom appears to have weakened slightly in the first half of the year relative to 2018 to a rate a little below its potential. The underlying pattern of relatively strong household consumption growth but weak business investment has persisted.

CPI inflation was 2.0% in May. It is likely to fall below the 2% target later this year, reflecting recent falls in energy prices. Core CPI inflation was 1.7% in May, and core services CPI inflation has remained slightly below levels consistent with meeting the inflation target in the medium term. The labour market remains tight, with recent data on employment, unemployment and regular pay in line with expectations at the time of the May Report. Growth in unit wage costs has remained at target-consistent levels.

The Committee continues to judge that, were the economy to develop broadly in line with its May Inflation Report projections that included an assumption of a smooth Brexit, an ongoing tightening of monetary policy over the forecast period, at a gradual pace and to a limited extent, would be appropriate to return inflation sustainably to the 2% target at a conventional horizon. The MPC judges at this meeting that the existing stance of monetary policy is appropriate.

The economic outlook will continue to depend significantly on the nature and timing of EU withdrawal, in particular: the new trading arrangements between the European Union and the United Kingdom; whether the transition to them is abrupt or smooth; and how households, businesses and financial markets respond. The appropriate path of monetary policy will depend on the balance of these effects on demand, supply and the exchange rate. The monetary policy response to Brexit, whatever form it takes, will not be automatic and could be in either direction. The Committee will always act to achieve the 2% inflation target.

The Art Of Credit Creation

Today we discuss how banks lend, and why the idea that bank deposits limit bank lending is plain wrong and helps to explain why home prices have exploded in recent years.

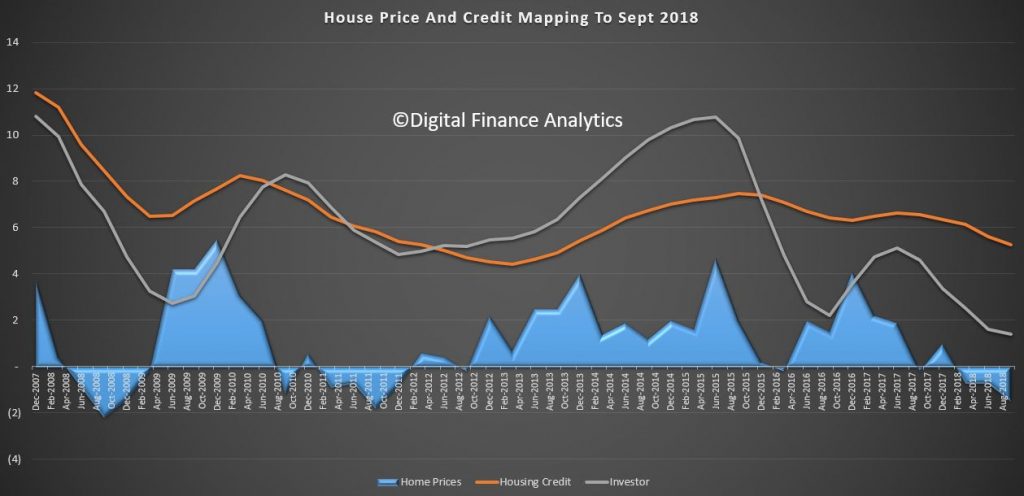

The correlation between home prices and credit availability are clear to see. We have updated this chart to take account of 2018 data. As credit rose from 2012 onward, home prices did too. It also suggests that if credit availability is tightened, we should expect prices to fall – take note, given the current tighter underwriting standards now in force. This is why I predict ongoing falls in property prices.

And more specifically, credit for property investment is even more strongly correlated. As we know investors are attracted by the capital growth, and also the capital gains and negative gearing tax breaks available.

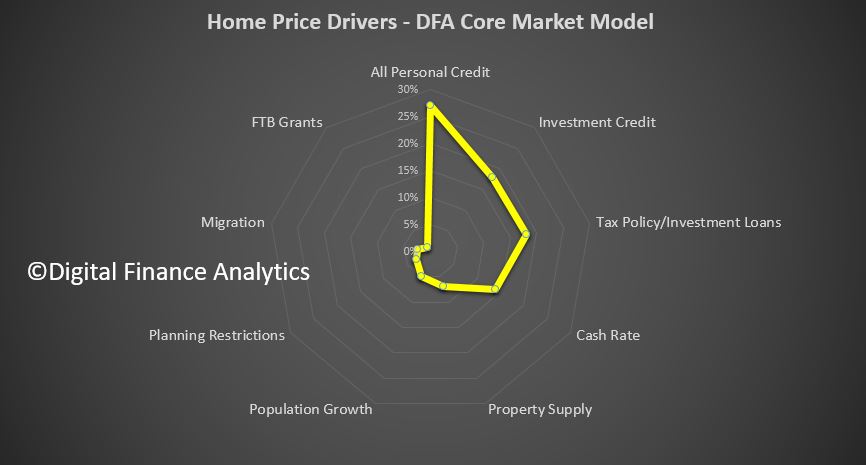

What’s most interesting is the relative weight of these different factors in driving home prices. The four most powerful levers in terms of home prices is first overall growth in personal credit, including mortgages and other loans at 27% of total impact. Investment lending contributed a further 18%, followed by tax policy for investment property at 17% and the cash rate at 14%. The other factors, the ones which are spoken about the most, property supply, population growth, planning restrictions and migration, together make up just 22% of total impact. Or in other words, without addressing the credit elephant in the room, tax policy and interest rates, the chances of taming prices is low. First time buyer incentives were less than 1%!

So the greatest of these is credit policy, which has for years allowed banks to magic money from thin air, to lend to borrowers, to drive up home prices, to inflate the banks balance sheet, to lend more to drive prices higher – repeat ad nauseam! Totally unproductive, and in fact it sucks the air out of the real economy and money directly out of punters wages, but make bankers and their shareholders richer. Plus, the second order impacts to the construction sector.

Two final observations. First the GDP calculation we use in Australia is flattered by housing growth (triggered by credit growth) and construction activity. The second driver of GDP growth is population growth. But in real terms neither of these are really creating true economic growth, as seen in the per capita data.

Second, the capital regulatory framework from the Bank For International Settlements is still a hangover from the days when deposits were thought to drive loans – so holding a ratio of assets to protect deposits made sense. But given the multiplier effect available to banks via their ability to issue bonds and the like increase their loan books, the BIS rules as currently formulated are ineffective. In fact by applying low risk weights to mortgage loans, they encourage to banks to leverage up more – in Australia our major banks have only about 5%of shareholder capital at risk. This is way too low.

To, conclude, to solve the property equation, and the economic future of the country, we have to address credit. But then again, I refer to the fact that most economists still think credit is unimportant in macroeconomic terms!

The alternative is to continue to let credit grow well above wages, and lift the already heavy debt burden even higher. In fact, some are calling for a reversal of recent credit tightening to resurrect home price growth. But, that is, ultimately unsustainable, and why there will be an economic correction in Australia, and quite soon.

UK Bank “Ring Fencing” Goes Live In 6 Weeks

In less than six weeks, ten years on from the financial crisis, one of the largest ever reforms to the structure of the UK banking industry comes into force. While most will notice little difference on day one, ring-fencing

the largest UK banks has involved significant changes behind the scenes.

The Bank of England says this reform will make the provision of core banking services more resilient, and protect taxpayers from further bail outs. These are real benefits but are conditional on the ring-fence being maintained over time, meaning this will be a continuous process for both the PRA and the banks.

This was outlined in a speech “From Construction to Maintenance: Patrolling the ring-fence” given by James Proudman, Executive Director, UK Deposit Takers Supervision.

Financial crises generate significant and persistent costs. The Bank of England has estimated that the costs of crises amount to 75% of GDP on average. The previous crisis resulted in the Government providing £65 billion of capital to RBS and Lloyds to prevent them failing and disrupting the provision of vital banking services to their customers. Since then, a comprehensive regulatory reform package was developed – which in large part has now been implemented – to reduce the likelihood that such a crisis could happen again.

A decade on from the financial crisis, one of the largest ever reforms to the structure of the UK banking industry is coming into force. By 1 January 2019, the largest UK banking groups must have implemented the ‘ring-fencing’ – or separation – of their UK retail business from their international and investment banking operations. This means that the core banking services on which retail and small business customers depend should not be threatened should things go wrong in wholesale financial markets or the global economy.

Banks have now largely completed the ring-fencing of their retail operations, and have done so with little disruption to their customers and counterparties. The PRA’s supervisory focus will turn to ensuring the ring-fences that have been established are effective in practice, and remain so. Ring-fencing both broadens the range of regulatory requirements, and increases the intensity of supervision, for the groups in scope. As such, ring-fencing will remain a focus for the PRA – as well as for the banks themselves – in the coming years.

All large UK banking groups – defined as those with ‘core’ retail deposits greater than £25 billion – are required to implement ring-fencing by 2019. Currently, seven banking groups cross this threshold. Between them, these groups have around £5 trillion of assets, both in the UK and overseas.

The ring-fencing regime is designed to be consistent with the other parts of the post-crisis regulatory framework. The most systemically-important ring-fenced banks will be held to higher capital requirements. The Systemic Risk Buffer will be applied to ring-fenced banks to ensure they are adequately capitalised and resilient to shocks. We expect ring-fenced banks to have, on average, around 1.5 percentage points more high-quality ‘Tier 1’ capital than non-systematically important banks. And a ring-fenced bank will not be able to be capitalised by debt raised externally by its group, which would give rise to so-called ‘double leverage’.

Overall, the Bank estimates that ring-fenced banks’ total loss absorbency will be, on average, around 27% of their risk-weighted assets, higher than the 17% recommended by the ICB. Ring-fencing also helps improve the resolvability of the big UK banking groups. The resolution strategy for groups including ring-fenced banks will typically involve a bail-in at the level of the holding company. Bail-in would recapitalise the relevant entity by passing losses up to the holding company to be borne by shareholders and debt-holders. This should stabilise the group. Structural separation then provides authorities with additional options as part of any subsequent restructuring.

Ring-fencing, together with other elements of the post-crisis regulatory landscape, means that the key providers of important retail banking services are less likely to fail following a shock to the economy or the financial system. But if banks do get into trouble, there will be greater certainty that important banking services will continue to be provided without disrupting customers and without the need for Government bail-outs. This is the key difference ring-fencing delivers should we experience a repeat of the financial crisis.

To comply with the legislation, each banking group has had to restructure to ensure that their new ring-fenced banks can meet prudential requirements on a standalone basis, have their own governance arrangements and have viable business models.

In some cases, a banking group’s ring-fenced bank has been established as a brand new legal entity. Setting up a bank from scratch is a considerable undertaking, even more so for a bank which will have millions of customers from day one. In fact, last year the PRA authorised the three largest new banks ever established in the UK. And by the end of this year, we will have assessed and approved more than 50 applications for senior management positions within these groups, and considered the suitability of their proposed prudential sub-groups, containing hundreds of entities between them. Ring-fencing also resulted in the Bank helping ring-fenced banks undertake around 20 on-boarding operations to payment systems settling across the books of the Bank, and admitting six banks to the Sterling Monetary Framework.

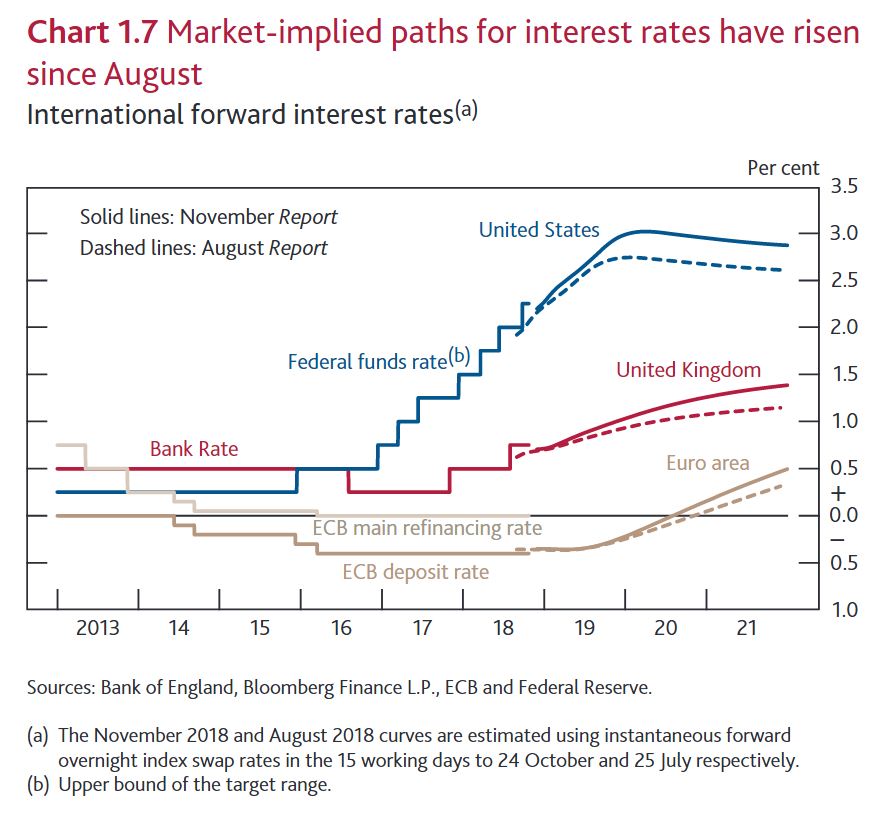

UK Expects Rate Rises Ahead

The Bank of England published their November 2018 inflation report overnight.

On one hand there was no change as “at its meeting ending on 31 October 2018, the MPC voted unanimously to maintain Bank Rate at 0.75%. The Committee voted unanimously to maintain the stock of sterling non-financial investment-grade corporate bond purchases, financed by the issuance of central bank reserves, at £10 billion. The Committee also voted unanimously to maintain the stock of UK government bond purchases, financed by the issuance of central bank reserves, at £435 billion”.

But the commentary highlighted the trend of higher rates ahead.

In August, the MPC raised Bank Rate to 0.75%. That had been anticipated well ahead of the announcement with most short‑term interest rates rising earlier in 2018).

In the run‑up to the November Report, stronger‑than‑expected activity and

inflation outturns, as well as increases in short‑term interest rates internationally, have pushed up the market‑implied path for Bank Rate. It is now expected to reach around 1.4% in three years’ time, up from 1.1% in August.

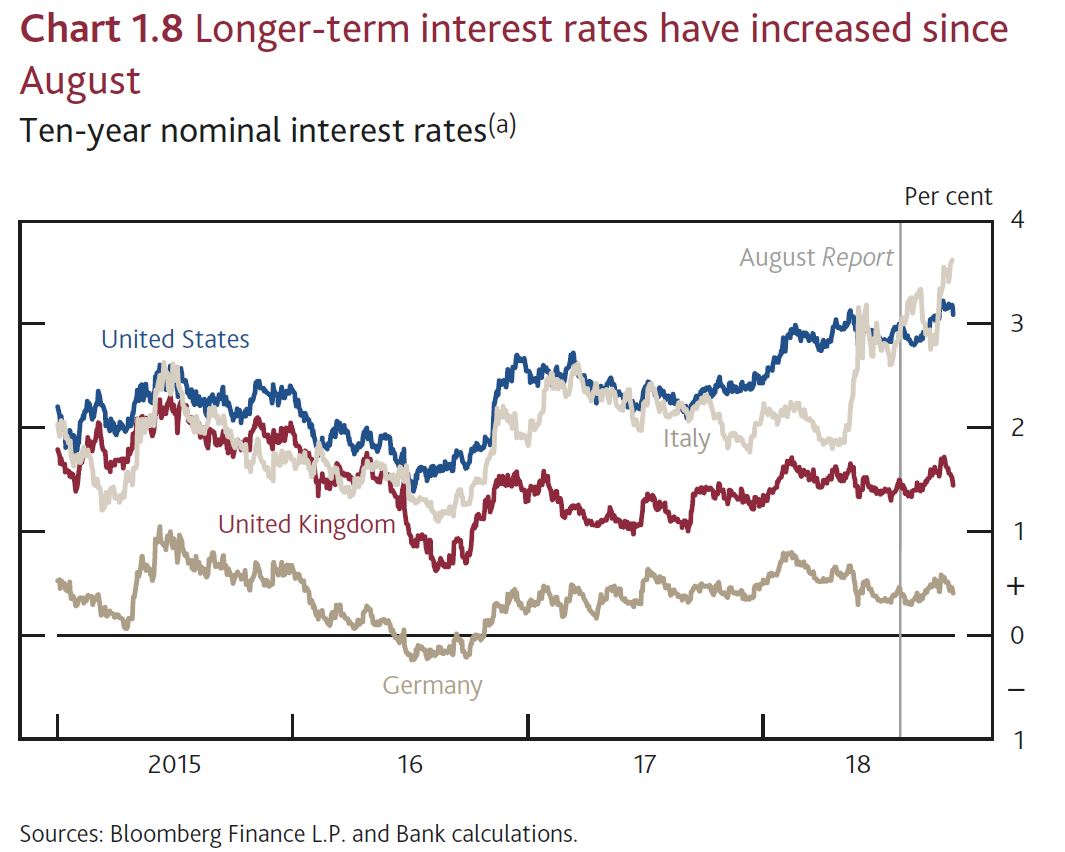

Long‑term UK interest rates have also risen since August, despite falling back in the run‑up to the November Report. Those rates have been affected in part by the increase in long‑term interest rates in other countries.

Unless there is a disorderly Brexit, it seems the market is now expecting 3 rate rises of 25 basis points ahead. As a result the pound moved higher.

Unless there is a disorderly Brexit, it seems the market is now expecting 3 rate rises of 25 basis points ahead. As a result the pound moved higher.