Wayne Byres speech “Fortis Fortuna Adiuvat: Fortune Favours the strong”, as Chairman of APRA, at the AFR Banking & Wealth Summit, makes two significant points.

First, there are elevated risks in the residential lending sector (even after the recent tactical announcements on interest only loans). Banks remain highly leveraged businesses.

Second, despite the delays from Basel, APRA will consult this year on potential changes to the capital ratios, reflecting the Australian Banks’ focus on mortgage lending and the need to be “unquestionably strong”.

A further indication that mortgage costs will continue to rise!

In the past few days, there has been a great deal of attention given to our recent announcement on additional measures to strengthen one particular part of the financial system: the residential mortgage lending market. These measures build on the steps we have taken over the past two years to bolster loan underwriting practices and moderate investor lending, in an environment that we considered to be one of heightened risk.

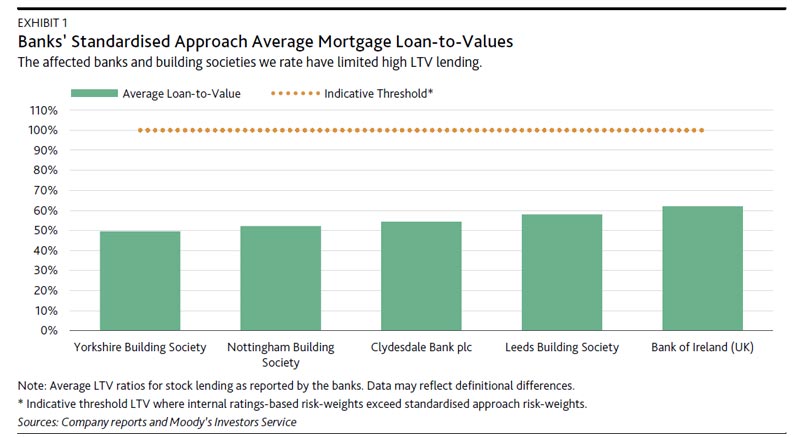

Those measures had a positive impact (Chart 1), but at the same time the risk environment certainly hasn’t moderated:

- house prices remain high;

- household income growth remains subdued;

- the already high ratio of household debt to income has got higher;

- the already low official cash rate has got lower (although not all of this reduction has flowed to borrowers, particularly investors; and

- competitive pressures haven’t diminished.

It’s important to be clear that our goal in implementing the additional measures we announced on Friday is not to determine house prices. Housing prices are not within the control, nor the mandate, of the prudential regulator. Nor, as the Reserve Bank Governor said last night, can prudential measures address underlying supply-demand issues within the housing market. Rather, our role in the current environment is to promote a higher-than-normal degree of prudence – definitely by lenders and, ideally, also borrowers – in both credit decisions and balance sheet strength. On this occasion, we have focussed on interest-only lending to complement our earlier measures. Although there are perfectly legitimate reasons why individual borrowers might prefer an interest-only loan, in aggregate the level of interest-only lending creates additional vulnerabilities and we came to the view some additional moderation in this area was warranted.

We chose not to lower the investor lending growth benchmark at this point in time, given the need to accommodate the increasing supply of housing in the construction pipeline. However, limitations on the volume of new interest-only lending will impact investors more acutely than owner-occupiers, given that around two-thirds of lending to investors is on an interest-only basis. Furthermore, although the 12-month annual growth rate for investor lending is currently below the 10 per cent benchmark, the run rate in more recent months has been closer to (if not a little above) 10 per cent on an annualised basis. Therefore, even with the benchmark unchanged, lenders are still likely to have to tighten their lending practices and slow lending from that in recent months to ensure they remain comfortably below the desired level.

This latest step is a tactical response to current market conditions – we can and will do more (or less) as conditions evolve. We also developing a more strategic response that recognises that, in the Australian banking system, housing lending risks and capital adequacy are far from independent issues.

The banking system certainly has higher capital adequacy ratios than it used to. But overall leverage has not materially declined. The proportion of equity that is funding banking system assets has improved only modestly, from a touch under 6 per cent a decade ago to just on 6½ per cent at the end of 2016. Notwithstanding the extra capital that new regulation has required, banking remains a highly leveraged business.

Unquestionably strong

One way to think about our objective in establishing ‘unquestionably strong’ capital requirements is that we should be able to assert, with credibility, that the banking system can withstand reasonably foreseeable adversity and continue to provide its core function of financial intermediation for the Australian community.

Unfortunately, there is no universal measure of financial strength that provides a clear cut answer to that test. So we need to be able to look at this question through multiple lenses. In thinking about the concept of ‘unquestionably strong’, there are three basic ways to do that:

- relative measures: the FSI adopted a relative approach in suggesting that unquestionably strong regulatory capital ratios would be positioned in the top quartile of international peers. We have said on a number of occasions that we do not intend to tie ourselves mechanically to some particular percentile, but top quartile positioning is a useful sense check which we can certainly use to guide our policy-making.

- alternative measures: regulators do not have exclusive domain over measures of financial strength. There are a range of alternative measures, such as those used by rating agencies, which can be used to benchmark Australian banks. Again, we do not intend to tie ourselves too closely to these measures, but it would be difficult to argue the banking system is unquestionably strong if alternative measures of capital strength, particularly those that are influential in investment decision-making, were to suggest something to the contrary.

- absolute measures: relative and alternative measures are useful guides, but the real test for a bank to claim it is unquestionably strong is whether it can comfortably survive extreme but plausible adversity. So stress testing, which doesn’t rely on relativities with other banks, or competing measures of strength, provides another useful guide for us.

Using multiple measures will provide useful insights on the banking system’s strength, but unfortunately will be unlikely to give us a single ‘right’ answer. At best it will provide a range for possible calibration which would reasonably meet our objective that, whichever lens you look through, we can credibly claim to have capital standards that produce an unquestionably strong banking system. We will still need to exercise judgement, taking account of other dimensions of risk within the system – both quantitative (such as liquidity and funding) and qualitative (such as risk management and risk culture within banks, and the strengths of the statutory framework and crisis management powers on which the stability of the system is built). Inevitably, some will argue the calibration should be higher, and others think it too high, but at the very least our logic and rationale should be transparent, and we can readily explain how our decisions are consistent with the FSI’s intent.As things stand today, our plan is to issue an information paper around the middle of the year, which will set out how we view the banking system through the various lenses that I have just mentioned, the extent of further strengthening required, and the timeframe over which that can be achieved in an orderly manner.

Beyond establishing the aggregate level of capital, we will need to follow that up with consultation on how the regulatory framework should allocate that capital across the different types of risk exposure. Some of those changes will flow from the inevitable direction of the work in Basel that I referred to earlier: this will include, for example, greater limitations on the use of internal credit risk models, and the inevitable removal of operational risk models. These changes will primarily impact the larger banks.

But, coming back to my starting point, probably the biggest issue we will need to resolve in ensuring capital is appropriately allocated is whether and how we adjust the risk weights for housing-related exposures. Our announcement last week reflected a tactical response to current conditions in the housing market. We will continue to refine these sorts of measures as long as they are needed. But a longer term and more strategic response will involve a review, during the course of our work on ‘unquestionably strong’, of the relative and absolute capital requirements for housing exposures. That should not be taken to imply that there will be a dramatic increase in capital requirements for housing lending: APRA has always imposed capital requirements for housing exposures that are well above international minimum standards, so we do not start with glaring deficiencies. By anyone’s standard, however, we have a banking system that has a notable concentration in housing. It is therefore important we give that issue particular attention as we think about how to put the concept of ‘unquestionably strong’ into practice.