The second consultative document on Revisions to the Standardised Approach for credit risk has been released for discussion.

There are a number of significant changes to residential property risk calculations . These guidelines will eventually become part of “Basel III/IV”, and will apply to banks not using their internal assessments (which are also being reviewed separately).

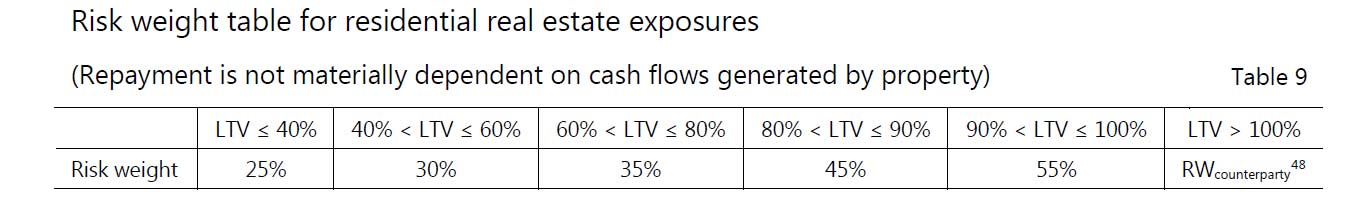

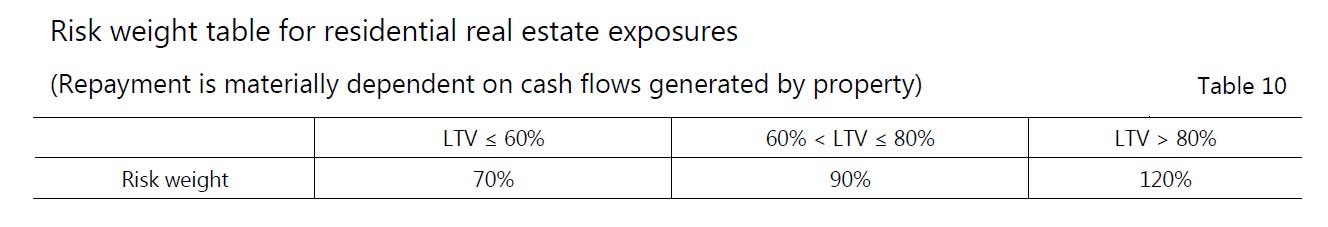

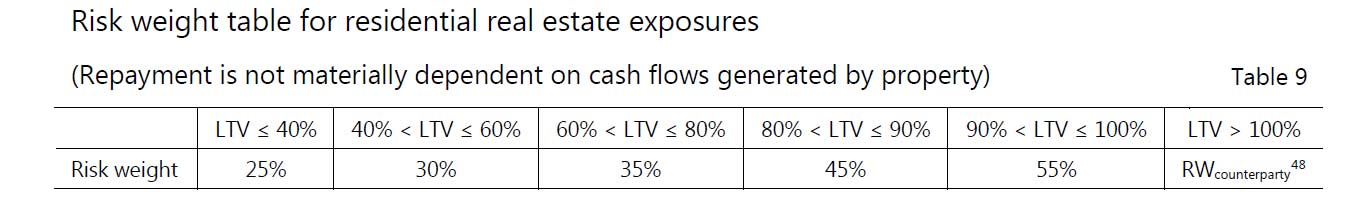

First, risk will be assessed by loan to value ratios, with higher LVR’s having higher risk weights. Second, investment property will have a separate a higher set of LVR related risk-weights. Third, debt servicing ratios will not directly be used for risk weights, but will still figure in the underwriting assessments.

There are also tweaks to loans to SME’s.

These proposals differ in several ways from an initial set of proposals published by the Committee in December 2014. That earlier proposal set out an approach that removed all references to external credit ratings and assigned risk weights based on a limited number of alternative risk drivers. Respondents to the first consultative document expressed concerns, suggesting that the complete removal of references to ratings was unnecessary and undesirable. The Committee has decided to reintroduce the use of ratings, in a non-mechanistic manner, for exposures to banks and corporates. The revised proposal also includes alternative approaches for jurisdictions that do not allow the use of external ratings for regulatory purposes.

The proposed risk weighting of real estate loans has also been modified, with the loan-to-value ratio as the main risk driver. The Committee has decided not to use a debt service coverage ratio as a risk driver given the challenges of defining and calibrating a global measure that can be consistently applied across jurisdictions. The Committee instead proposes requiring the assessment of a borrower’s ability to pay as a key underwriting criterion. It also proposes to categorise all exposures related to real estate, including specialised lending exposures, under the same asset class, and apply higher risk weights to real estate exposures where repayment is materially dependent on the cash flows generated by the property securing the exposure.

This consultative document also includes proposals for exposures to multilateral development banks, retail and defaulted exposures, and off-balance sheet items.The credit risk standardised approach treatment for sovereigns, central banks and public sector entities are not within the scope of these proposals. The Committee is considering these exposures as part of a broader and holistic review of sovereign-related risks.

Comments on the proposals should be made by Friday 11 March 2016.

Looking in more detail at the property-related proposals, the following risk weights will be applied to loans against real property:

- which are finished properties

- covered by a legal mortgage

- with a valid claim over the property in case of default

- where the borrower has proven ability to repay – including defined DSR’s

- with a prudent valuation (and in a falling market, a revised valuation), to derive a valid LVR

- all documentation held

If all criteria a met the following risk weights are proposed.

For residential real estate exposures to individuals with an LTV ratio higher than 100% the risk weight applied will be 75%. For residential real estate exposures to SMEs with an LTV ratio higher than 100% the risk weight applied will be 85%. If criteria are not met, then 150% will apply.

For residential real estate exposures to individuals with an LTV ratio higher than 100% the risk weight applied will be 75%. For residential real estate exposures to SMEs with an LTV ratio higher than 100% the risk weight applied will be 85%. If criteria are not met, then 150% will apply.

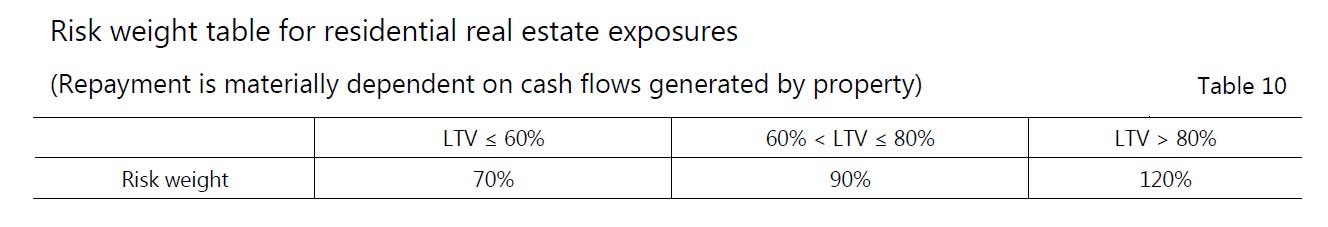

Turning to investment property, where cash flow from the property is the primary source of income to service the loan

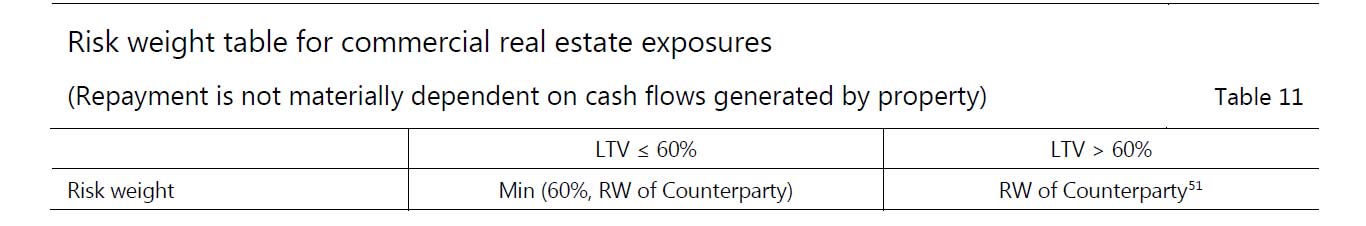

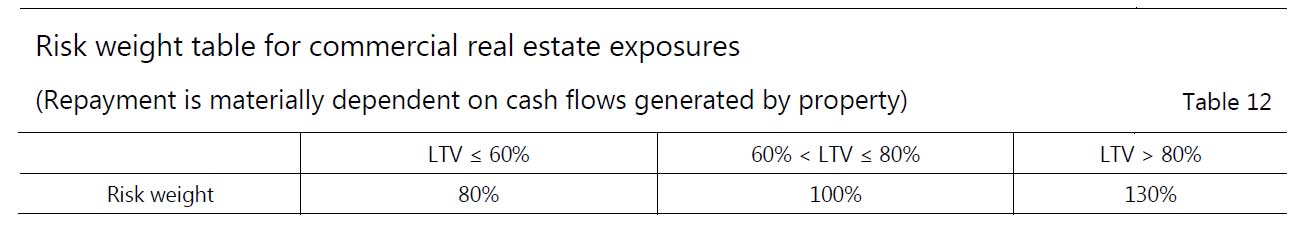

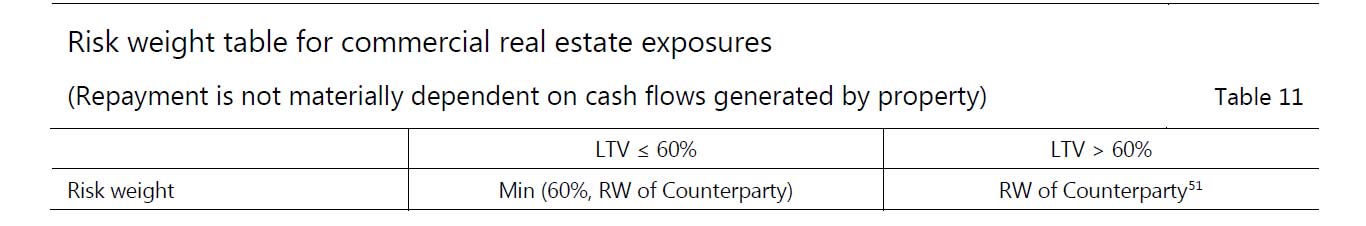

Commercial property will have different ratios, based on counter party risk weight.

Commercial property will have different ratios, based on counter party risk weight.

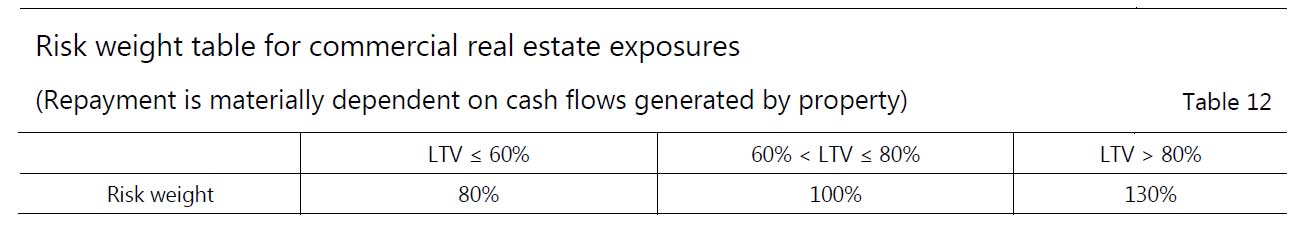

But again, those properties serviced by cash flow have higher weightings.

But again, those properties serviced by cash flow have higher weightings.

Development projects will be rated at 150%.

Development projects will be rated at 150%.

Bearing in mind that residential property today has a standard weight of 35%, it is clear that more capital will be required for high LVR and investment loans. As a result, if these proposals were to be adopted, then borrowers can expect to pay more for investment loans, and higher LVR loans.

It will also increase the burden of compliance on banks, and this will likely increase underwriting costs. Finally, whilst ongoing data on DSR will not be required, there is still a need to market-to-market in a falling market to ensure the LVR’s are up to date. This means, that if property valuations fall significantly, higher risk weights will start to apply, the further they fall, the larger the risk weights.

Finally, it continues the divergence between the relative risks of investment and owner occupied loans, the former demanding more capital, thus increasing the differential pricing of investment loans.

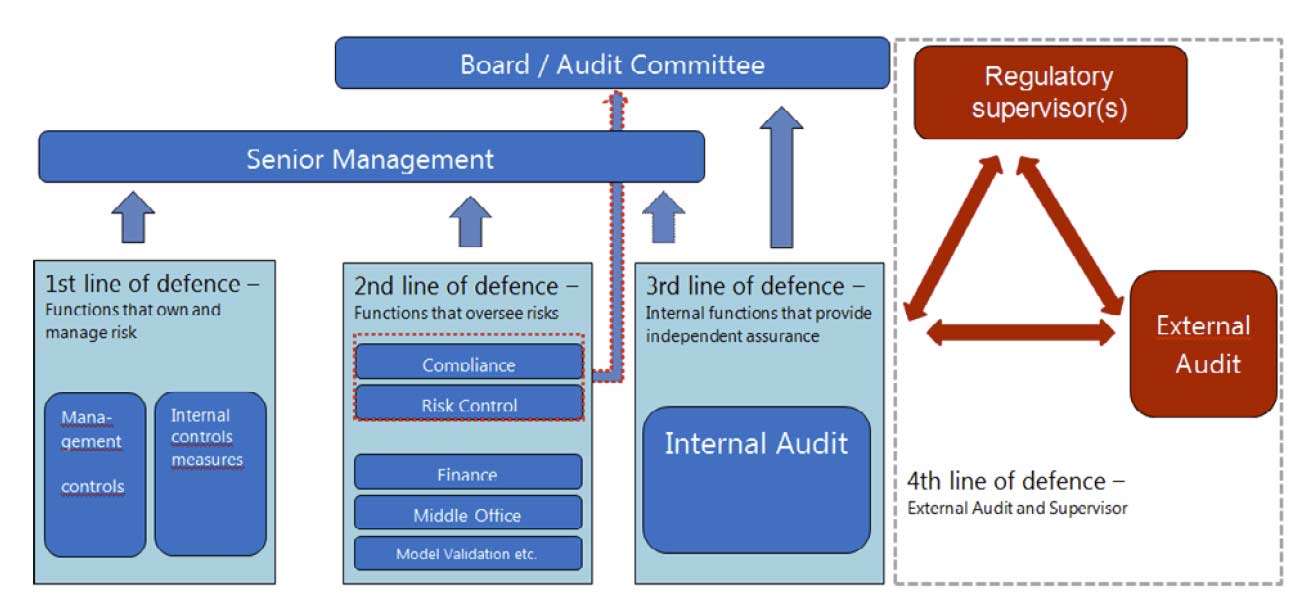

The Committee notes that the SA is a global minimum standard and that it is not possible to take into account all national characteristics in a simple approach. As such, national supervisors should require a more conservative treatment if they consider it necessary to reflect jurisdictional specificities. Furthermore, the SA is a methodology for calculating minimum risk-based capital requirements and should in no way be seen as a substitute for prudent risk management by banks.

Now, some will argue that in Australia, this will not impact the market much, as the major banks use their own internal models, however, as these are under review (with the intent of closing the gap somewhat with the standard methods used by the smaller players) expect the standard models to inform potential changes in the IRB set. Also, it is not clear yet whether banks who use lenders mortgage insurance for loans above 80% will be protected from the higher capital bands, though we suspect they may not. Non-bank lenders may well benefit as they are not caught by the rules, although capital market pricing may well change, and impact them at a second order level. We will be interested to see how local regulators handle the situation where an investment loan is partly serviced by income from rentals, and partly from direct income, which rules should apply – how will “materially dependent” be interpreted?