In December 2014, The Bank For International Settlements issued proposed Revisions to the Standardised Approach for credit risk for comment. It proposes an additional level of complexity to the capital calculations which are at the heart of international banking supervision. Comments on the proposals were due by 27 March 2015. These latest proposals, which have unofficially been dubbed “Basel IV”, is a continuation of the refining of the capital adequacy ratios which guide banking supervisors and relate to the standardised approach for credit risk. It forms part of broader work on reducing variability in risk-weighted asset. We want to look in detail at the proposals relating to residential real estate, because if adopted they would change the capital landscape considerably. Note this is separate from the proposal relating to the adjustment of IRB (internal model) banks. Whilst it aspires to simplify, the proposals are, to put it mildly, complex

For the main exposure classes under consideration, the key aspects of the proposals are:

- Bank exposures would no longer be risk-weighted by reference to the external credit rating of the bank or of its sovereign of incorporation, but they would instead be based on a look-up table where risk weights range from 30% to 300% on the basis of two risk drivers: a capital adequacy ratio and an asset quality ratio.

- Corporate exposures would no longer be risk-weighted by reference to the external credit rating of the corporate, but they would instead be based on a look-up table where risk weights range from 60% to 300% on the basis of two risk drivers: revenue and leverage. Further, risk sensitivity would be increased by introducing a specific treatment for specialised lending.

- The retail category would be enhanced by tightening the criteria to qualify for the 75% preferential risk weight, and by introducing a fallback subcategory for exposures that do not meet the criteria.

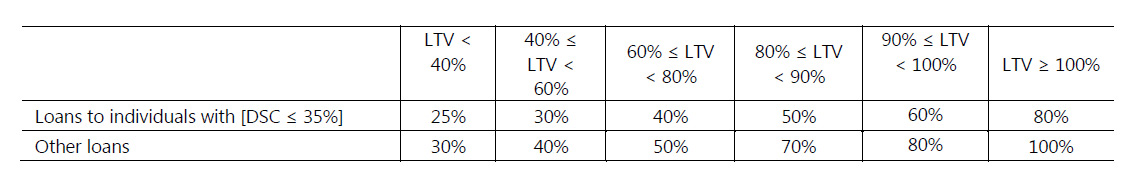

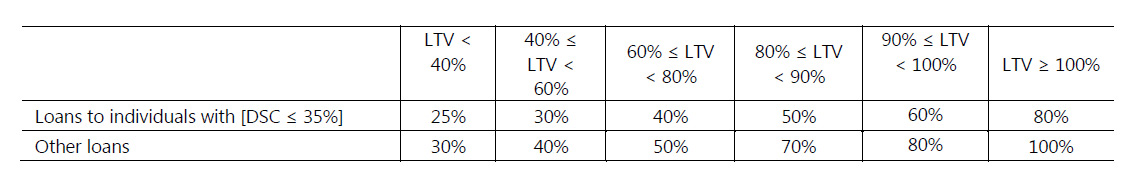

- Exposures secured by residential real estate would no longer receive a 35% risk weight. Instead, risk weights would be determined according to a look-up table where risk weights range from 25% to 100% on the basis of two risk drivers: loan-to-value and debt-service coverage ratios.

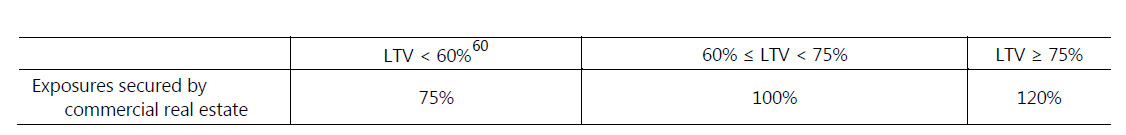

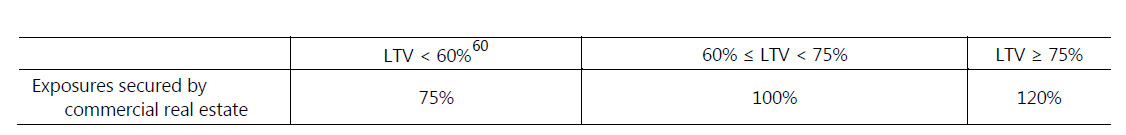

- Exposures secured by commercial real estate are subject to further consideration where two options currently envisaged are: (a) treating them as unsecured exposures to the counterparty, with a national discretion for a preferential risk weight under certain conditions; or (b) determining the risk weight according to a look-up table where risk weights range from 75% to 120% on the basis of the loan-to-value ratio.

- The credit risk mitigation framework would be amended by reducing the number of approaches, recalibrating supervisory haircuts, and updating corporate guarantor eligibility criteria.

Real Estate Capital Calculation Proposals

The recent financial crisis has demonstrated that the current treatment is not sufficiently risk-sensitive and that its calibration is not always prudent. In order to increase the risk sensitivity of real estate exposures, the Committee proposes to introduce two specialised lending categories linked to real estate (under the corporate exposure category) and specific operational requirements for real estate collateral to qualify the exposures for the real estate categories.

Currently the standardised approach contains two exposure categories in which the risk-weight treatment is based on the collateral provided to secure the relevant exposure, rather than on the counterparty of that exposure. These are exposures secured by residential real estate and exposures secured by commercial real estate. Currently, these categories receive risk weights of 35% and 100%, respectively, with a national discretion to allow a preferential risk weight under certain strict conditions in the case of commercial real estate.

Residential Owner Occupied Real Estate

In order to qualify for the risk-weight treatment of a residential real estate exposure, the property securing the mortgage must meet the following operational requirements:

- Finished property: the property securing a mortgage must be fully completed. Subject to national discretion, supervisors may apply the risk-weight treatment for loans to individuals that are secured by an unfinished property, provided the loan is for a one to four family residential housing unit.

- Legal enforceability: any claim (including the mortgage, charge or other security interest) on the property taken must be legally enforceable in all relevant jurisdictions. The collateral agreement and the legal process underpinning the collateral must be such that they provide for the bank to realise the value of the collateral within a reasonable time frame.

- Prudent value of property: the property must be valued for determining the value in the LTV ratio. Moreover, the value of the property must not be materially dependent on the performance of the borrower. The valuation must be appraised independently using prudently conservative valuation criteria and supported by adequate appraisal documentation.

The current standardised approach applies a 35% risk weight to all exposures secured by mortgage on residential property, regardless of whether the property is owner-occupied, provided that there is a substantial margin of additional security over the amount of the loan based on strict valuation rules. Such an approach lacks risk sensitivity: a 35% risk weight may be too high for some exposures and too low for others. Additionally, there is a lack of comparability across jurisdictions as to how great a margin of additional security is required to achieve the 35% risk weight.

In order to increase risk sensitivity and harmonise global standards in this exposure category, the Committee proposes to introduce a table of risk weights ranging from 25% to 100% based on the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio. The Committee proposes that the risk weights derived from the table be applied to the full exposure amount (ie without tranching the exposure across different LTV buckets).

The Committee believes that the LTV ratio is the most appropriate risk driver in this exposure category as experience has shown that the lower the outstanding loan amount relative to the value of the residential real estate collateral, the lower the loss incurred in the event of a default. Furthermore, data suggest that the lower the outstanding loan amount relative to the value of the residential real estate collateral, the less likely the borrower is to default. For the purposes of calculating capital requirements, the value of the property (ie the denominator of the LTV ratio) should be measured in a prudent way. Further, to dampen the effect of cyclicality in housing values, the Committee is considering requiring the value of the property to be kept constant at the value calculated at origination. Thus, the LTV ratio would be updated only as the loan balance (ie the numerator) changes.

The LTV ratio is defined as the total amount of the loan divided by the value of the property. For regulatory capital purposes, when calculating the LTV ratio, the value of the property will be kept constant at the value measured at origination, unless an extraordinary, idiosyncratic event occurs resulting in a permanent reduction of the property value. Modifications made to the property that unequivocally increase its value could also be considered in the LTV. The total amount of the loan must include the outstanding loan amount and any undrawn committed amount of the mortgage loan. The loan amount must be calculated gross of any provisions and other risk mitigants, and it must include all other loans secured with liens of equal or higher ranking than the bank’s lien securing the loan. If there is insufficient information for ascertaining the ranking of the other liens, the bank should assume that these liens rank pari passu with the lien securing the loan.

In addition, as mortgage loans on residential properties granted to individuals account for a material proportion of banks’ residential real estate portfolios, to further increase the risk sensitivity of the approach, the Committee is considering taking into account the borrower’s ability to service the mortgage, a proxy for which could be the debt service coverage (DSC) ratio. Exposures to individuals could receive preferential risk weights as long as they conform to certain requirement(s), such as a ‘low’ DSC ratio. This ratio could be defined on the basis of available income ‘net’ of taxes. The DSC ratio would be used as a binary indicator of the likelihood of loan repayment, ie loans to individuals with a DSC ratio below a certain threshold would qualify for preferential risk weights. The threshold could be set at 35%, in line with observed common practice in several jurisdictions. Given the difficulty in obtaining updated borrower income information once a loan has been funded, and also given concerns about introducing cyclicality in capital requirements, the Committee is considering whether the DSC ratio should be measured only at loan origination (and not updated) for regulatory capital purposes.

The DSC ratio is defined as the ratio of debt service payments (including principal and interest) relative to the borrower’s total income over a given period (eg on a monthly or yearly basis). The DSC ratio is defined using net income (ie after taxes) in order to focus on freely disposable income. The DSC ratio must be prudently calculated in accordance with the following requirements:

- Debt service amount: the calculation must take into account all of the borrower’s financial obligations that are known to the bank. At loan origination, all known financial obligations must be ascertained, documented and taken into account in calculating the borrower’s debt service amount. In addition to requiring borrowers to declare all such obligations, banks should perform adequate checks and enquiries, including information available from credit bureaus and credit reference agencies.

- Total income: income should be ascertained and well documented at loan origination. Total income must be net of taxes and prudently calculated, including a conservative assessment of the borrower’s stable income and without providing any recognition to rental income derived from the property collateral. To ensure the debt service is prudently calculated, the bank should take into account any probable upward adjustment in the debt service payment. For instance, the loan’s interest rate should (for this purpose) be increased by a prudent margin to anticipate future interest rate rises where its current level is significantly below the loan’s long-term level. In addition, any temporary relief on repayment must not be taken into account for purposes of the debt service amount calculation.

Notwithstanding the definitions of the DSC and LTV ratios, banks must, on an ongoing basis, have a comprehensive understanding of the risk characteristics of their residential real estate portfolio.

The risk weight applicable to the full exposure amount will be assigned, as determined by the table below, according to the exposure’s loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, and in the case of exposures to individuals, also taking into account the debt service coverage (DSC) ratio. Banks should not tranche their exposures across different LTV buckets; the applicable risk weight will apply to the full exposure amount. A bank that does not have the necessary LTV information for a given residential real estate exposures must apply a 100% risk weight to such an exposure.

Some points to note.

Some points to note.

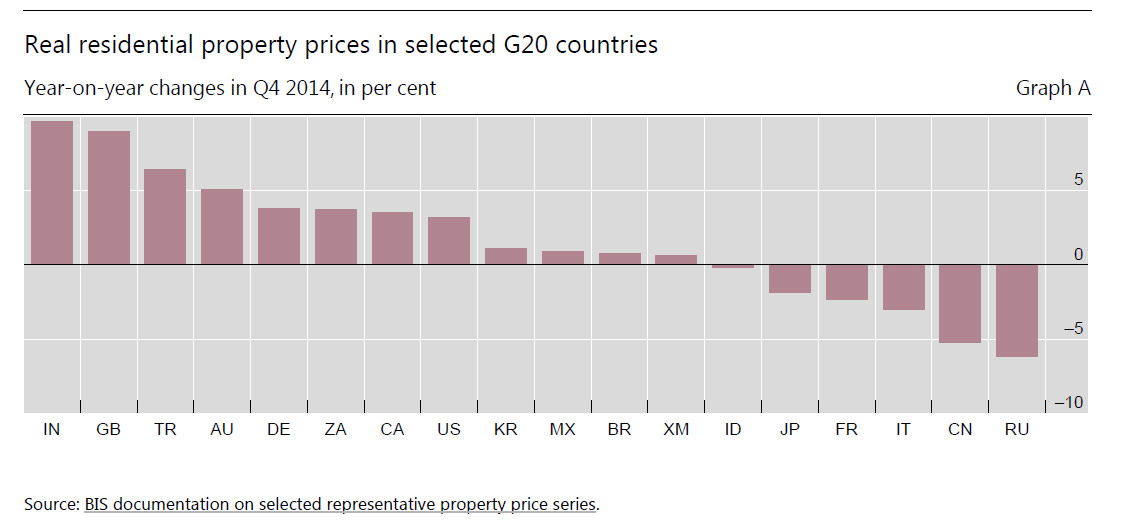

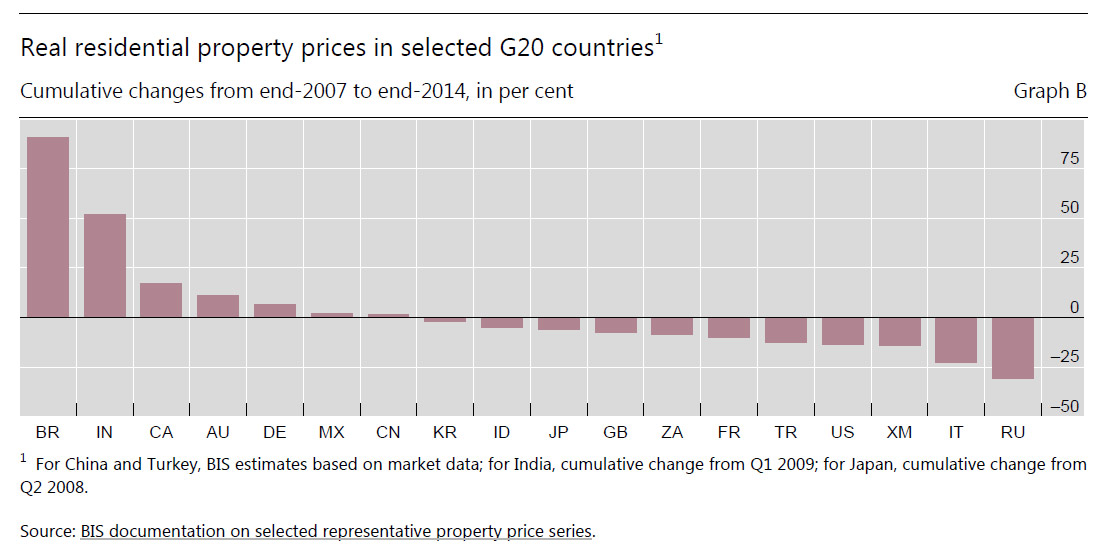

- Differences in real estate markets, as well as different underwriting practices and regulations across jurisdictions make it difficult to define thresholds for the proposed risk drivers that are meaningful in all countries.

- Another concern is that the proposal uses risk drivers prudently measured at origination. This is mainly to dampen the effect of cyclicality in housing values (in the case of LTV ratios) and to reduce regulatory burden (in the case of DSC ratios). The downside is that both risk drivers can become less meaningful over time, especially in the case of DSC ratios, which can change dramatically after the loan has been granted.

- The DSC ratio is defined using net income (ie after taxes) in order to focus on freely disposable income. That said, the Committee recognises that differences in tax regimes and social benefits in different jurisdictions make the concept of ‘available income’ difficult to define and there are concerns that the proposed definition might not be reflective of the borrower’s ability to repay a loan. Further, the level at which the DSC threshold ratio has been set might not be appropriate for all borrowers (eg high income) or types of loans (eg those with short amortisation periods). Therefore the Committee will explore whether using either a different definition of the DSC ratio (eg using gross income, before taxes) or any other indicator, such as a debt-to-income ratio, could better reflect the borrower’s ability to service the mortgage.

- There are no specific proposal to treat loans that are past-due for more than 90 days.

Investment Loans

Bearing in mind that 35% of all loans are for investment purposes in Australia, the proposals relating to loans for investment purposes are important. So how will they be treated under Basel 4?

There are a number of pointers in the proposals, though its not totally clear in our view. First, we think the proposals would apply to separate loans where repayment is predicated on income generated by the property securing the mortgage, i.e. investment loans rather than a normal loans where the mortgage is linked directly to the underlying capacity of the borrower to repay the debt from other sources. Such loans might fall into a special commercial real estate category, specialist lending category, or a fall back to the unsecured category, each with different sets of capital weights.

The Committee proposes that any exposure secured with real estate that exhibits all of the characteristics set out in the specialised lending category should be treated for regulatory capital purposes as income-producing real estate or as land acquisition, development and construction finance as the case may be, rather than as exposures secured by real estate. Any non-specialised lending exposure that is secured by real estate but does not satisfy the operational requirements should be treated for regulatory capital purposes as an unsecured exposure, either as a corporate exposure or other retail exposure, as appropriate.

Specialised lending exposure, would be defined so if all the following characteristics, either in legal form or economic substance were met:

- The exposure is typically to an entity (often a special purpose entity (SPE)) that was created specifically to finance and/or operate physical assets;

- The borrowing entity has few or no other material assets or activities, and therefore little or no independent capacity to repay the obligation, apart from the income that it receives from the asset(s) being financed;

- The terms of the obligation give the lender a substantial degree of control over the asset(s) and the income that it generates; and

- As a result of the preceding factors, the primary source of repayment of the obligation is the income generated by the asset(s), rather than the independent capacity of a broader commercial enterprise.

On the other hand, in order to qualify as a commercial real estate exposure, the property securing the mortgage must meet the same operational requirements as for residential real estate. If the loan is a commercial real estate category, the risk weight applicable to the full exposure amount will be assigned according to the exposure’s loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, as determined in the table below. Banks should not tranche their exposures across different LTV buckets; the applicable risk weight will apply to the full exposure amount. A bank that does not have the necessary LTV information for a given commercial real estate exposure must apply a 120% risk weight.

LTV Note, if this LTV refers to market value, the threshold should be set at a lower level: eg 50%.

Note, if this LTV refers to market value, the threshold should be set at a lower level: eg 50%.

Where the requirements are not met, the exposure will be considered unsecured and treated according to the counterparty, ie as “corporate” exposure or as “other retail”. However, in exceptional circumstances for well developed and long established markets, exposures secured by mortgages on office and/or multipurpose commercial premises and/or multi-tenanted commercial premises may be risk-weighted at [50%] for the tranche of the loan that does not exceed 60% of the loan to value ratio. This exceptional treatment will be subject to very strict conditions, in particular:

- the exposure does not meet the criteria to be considered specialised lending

- the risk of loan repayment must not be materially dependent upon the performance of, or income generated by, the property securing the mortgage, but rather on the underlying capacity of the borrower to repay the debt from other sources

- the property securing the mortgage must meet the same operational requirements as for residential real estate

- two tests must be fulfilled, namely that (i) losses stemming from commercial real estate lending up to the lower of 50% of the market value or 60% of loan-to value (LTV) based on mortgage-lending-value (MLV) must not exceed 0.3% of the outstanding loans in any given year; and that (ii) overall losses stemming from commercial real estate lending must not exceed 0.5% of the outstanding loans in any given year. This is, if either of these tests is not satisfied in a given year, the eligibility to use this treatment will cease and the original eligibility criteria would need to be satisfied again before it could be applied in the future. Countries applying such a treatment must publicly disclose that these and other additional conditions (that are available from the Basel Committee Secretariat) are met. When claims benefiting from such exceptional treatment have fallen past-due, they will be risk-weighted at [100%].

Implications and Consequences

We should make the point, these are proposals, and subject to change. But it would mean that banks using the standard approach to capital could no longer just go with a 35% weighting, rather they will need to segment the book based on LTV and servicability at a loan by loan level. Investment loans may become more complex and demand higher capital weighting. The required data may be available, as part of the loan origination process, but additional processes and costs will be incurred, and it appears net-net capital buffers will be raised for most players. The capital would be determined using two risk drivers: loan-to-value and debt-service coverage ratios with risk weights ranging from 25 percent to 100 percent. Investment loans may require different treatment, (and the RBNZ discussion paper recently issued may be relevant here, where investment loans are handled on a different basis.)

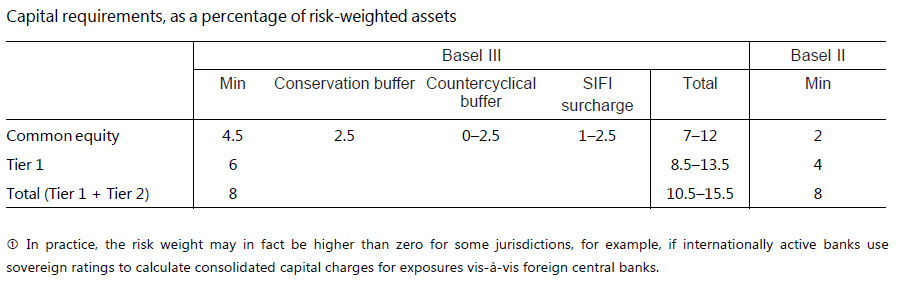

Finally, a word about those banks on IRB. Currently, under their internal models, they are sitting on an average weighting of around 17% (compared with 35% for standard banks). There are proposals to lift the floor to 20% minimum, and the FSI Inquiry recommend higher. Indeed, Murray called for the big banks to lift the average mortgage risk weighting to a range of 25% to 30%. This would bring them closer to the average mortgage risk weighting used by Australia’s regional banks and credit unions, though as described above, these, in turn, may change. Incidentally, the Bank of England thinks 35% is a good target. Basel 4 will also reduce the variance between standardised banks and those using their own models by requiring the internal models not to deviate from the RWA number in the standardised model by a certain amount: the so-called “capital floor”.

Interestingly the US is focussing on an additional measure, The Tier 1 Common measure, which is unweighted assets to capital, and has set a floor of 5%, or more. The Major Banks in Australia carry real, or non-risk-weighted, equity capital of just 3.7% of assets. Some banks are leveraged over seventy times the equity capital to loans, which is scarily high, but then the RBA (aka the tax payer) would bail them out if they get into trouble, so that’s OK (or not). This means that just $1.70 in assets will now support a $100 loan.

We wonder if the ever more complex models being proposed by Basel are missing the point. Maybe we should be going for something simpler. Many banks of course have invested big in advanced models to squeeze the capital lemon as hard as they can. But stepping back we need approaches which allow greater ability to compare across banks, and more transparent disclosure so we can see where the true risks lay. Certainly capital buffers should be lifted, but we suspect Basel 4, despite the best of intentions, is going down the wrong alley.