Interesting panel remarks at the IMF conference “Rethinking macro policy III: progress or confusion?” by Jaime Caruana, General Manager, Bank for International Settlements in Washington DC. The comments were entitled “The international monetary and financial system:eliminating the blind spot”.

Introduction

Thank you for inviting me to discuss the international monetary and financial system (IMFS) at this engaging conference. The design of international arrangements suitable for the global economy is a long-standing issue in economics. The global financial crisis has put this issue back on the policy agenda. In my panel remarks, I would like to concentrate on an important blind spot in the system. The current IMFS consists of domestically focused policies in a world of global firms, currencies and capital flows – but are local rules adequate for a global game ? I shall argue that liquidity conditions often spill over across borders and can amplify domestic imbalances to the point of instability. In other words, the IMFS as we know it today not only does not constrain the build-up of financial imbalances, it also does not make it easy for national authorities to see these imbalances coming.

Certainly, some actions have been taken to address this weakness in the system: the regulatory agenda has made significant progress in strengthening the resilience of the financial system. But we also know that risks and leverage will morph and migrate, and that the regulatory response by itself will not be enough. Other policies also have an important role to play. In particular, I shall argue that, in order to address this blind spot, central banks should take international spillovers and feedbacks – or spillbacks, as some may call them – into account, not least out of enlightened self-interest.

Local rules in a global game

Let me briefly characterise the present-day IMFS, before describing the spillover channels. In contrast to the Bretton Woods system or the gold standard, the IMFS today no longer has a single commodity or currency as nominal anchor. I am not proposing to go back to these former systems; rather, I will argue in favour of better anchoring domestic policies by taking financial stability considerations into account, internalising the interactions among policy regimes, and strengthening international cooperation so that we can establish better rules of the game.

So what are the rules of the game today? If there are any rules to speak of, they are mainly local. Most central banks target domestic inflation and let their currencies float, or follow policies consistent with managed or fixed exchange rates in line with domestic policy goals. Most central banks interpret their mandate exclusively in domestic terms. Moreover, the search for a framework that can satisfactorily integrate the links between financial stability and monetary policy is still work in progress with some way to go. The development and adoption of such a framework represent one of the most significant and difficult challenges for the central bank community over the next few years.When one looks at the international policy discussions, the main focus there is to contain balance of payments imbalances, with most attention paid to the current account (ie net flows) and not enough attention to gross flows and stocks – ie stocks of debt. This policy design does not help us see – much less constrain – the build-up of financial imbalances within and across countries. This, in my view, is a blind spot that is central to this debate. Global finance matters – and the game is undeniably global even if the rules that central banks play by are mostly local!

International spillover channels

Monetary regimes and financial conditions interact globally and reinforce each other. The strength and relevance of the spillovers and feedbacks tend to be underestimated. Let me briefly sketch four channels through which this happens. The first works through the conduct of monetary policy: easy monetary conditions in the major advanced economies spread to the rest of the world via policy reactions in the other economies (eg easing to resist currency appreciation and maintain competitiveness). This pattern goes beyond emerging market economies: many central banks have been keeping policy interest rates below those implied by traditional domestic benchmarks, as proxied by Taylor rules.

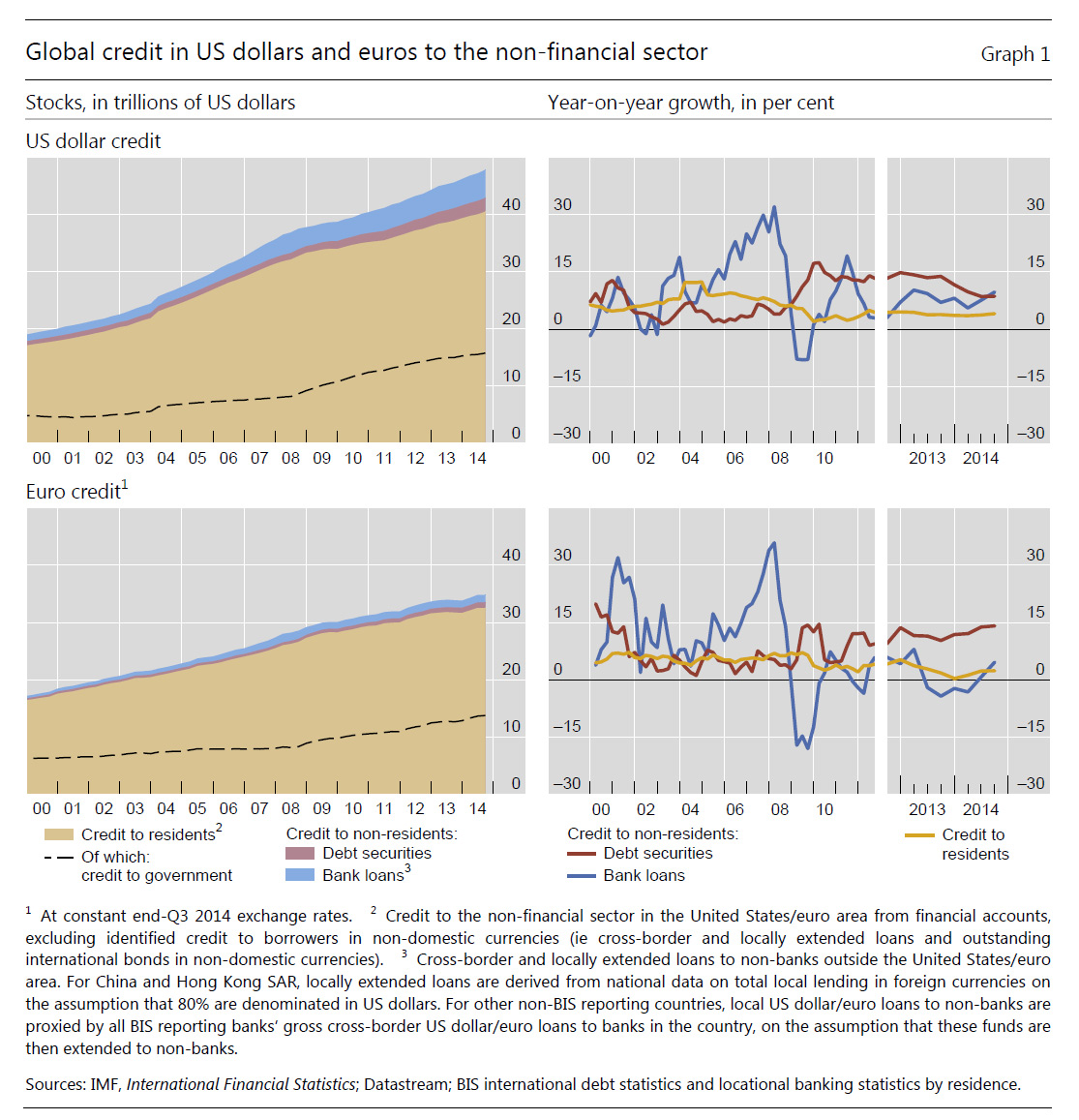

The second channel involves the international use of currencies: most notably, the domains of the US dollar and the euro extend so broadly beyond their respective domestic jurisdictions that US and euro area monetary policies immediately affect financial conditions in the rest of the world. The US dollar, followed by the euro, plays an outsize role in trade invoicing, foreign exchange turnover, official reserves and the denomination of bonds and loans. A key observation in this context is that US dollar credit to non-bank borrowers outside the United States has reached $9.2 trillion, and this stock expands on US monetary easing. In fact, under this monetary policy for the United States, US dollar credit has been expanding much faster abroad than at home (Graph 1, top right-hand panel).

Third, the integration of financial markets allows global common factors to move bond and equity prices. Uncertainty and risk aversion, as reflected in indicators such as the VIX index, affect asset markets and credit flows everywhere. In the new phase of global liquidity, where capital markets are gaining prominence and the search for yield is a driving force, risk premia and term premia in bond markets play an important role in the transmission of financial conditions across markets. This role has strengthened in the wake of central bank large-scale asset purchases. The Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchases compressed not only the US bond term premium, but also long-term yields in many other bond markets. More recently, the new programme of bond purchases in the euro area put downward pressure not only on European bond yields but apparently also on US bond yields, even amid expectations of US policy tightening.

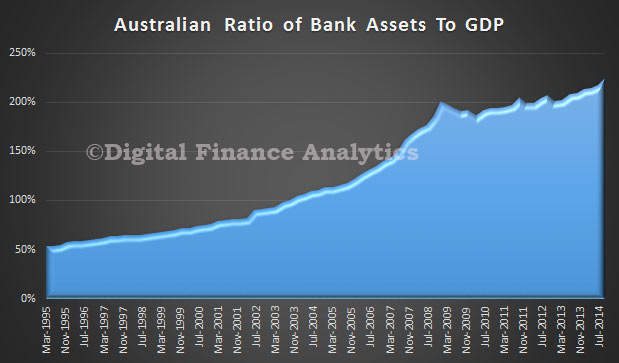

A fourth channel works through the availability of external finance in general, regardless of currency: capital flows provide a source of funding that can amplify domestic credit booms and busts. The leverage and equity of global banks jointly drive gross cross-border lending, and domestic currency appreciation can accelerate those inflows as it strengthens the balance sheets of local firms that have financed local currency assets with US dollar borrowing. In the run-up to the global financial crisis, for instance, cross-border bank lending contributed to raising credit-to-GDP ratios in a number of economies.

Through these channels, monetary and financial regimes can interact with and reinforce each other, sometimes amplifying domestic imbalances to the point of instability. Global liquidity surges and collapses as a result. What I have just described is the spillovers and feedbacks – and the tendency to create a global easing bias – with monetary accommodation at the centre. But these channels can also work in the opposite direction, amplifying financial tightening when policy rates in the centre begin to rise, or even seem ready to rise – as suggested by the taper tantrum of 2013. Nevertheless, it is an open question whether the effect of the IMFS is symmetric in this regard, creating as much of a tightening bias as it does an easing bias. In both cases, it is important to try to eliminate the blind spot and keep an eye on the dynamics of global liquidity.

Policy implications: from the house to the neighbourhood

This leads to my second point, that central banks should take the international effects of their own actions into account in setting monetary policy. This takes more than just keeping one’s own house in order; it will also require contributing to keeping the neighbourhood in order. An important precondition in this regard is the need to continue the work of incorporating financial factors into macroeconomics. If policymakers can better manage the broader financial cycle, that would in itself already help constrain excesses and reduce spillovers from one country to another.

But policymakers should also give more weight to international interactions, including spillovers, feedbacks and collective action problems, with a view to keeping the neighbourhood in order. How to start broadening one’s view from house to neighbourhood? One useful step would be to reach a common diagnosis, a consensus in our understanding of how international spillovers and spillbacks work. The widely held view that the IMFS should focus on large current account imbalances, for instance, does not fully capture the multitude of spillover channels that are relevant in this regard.

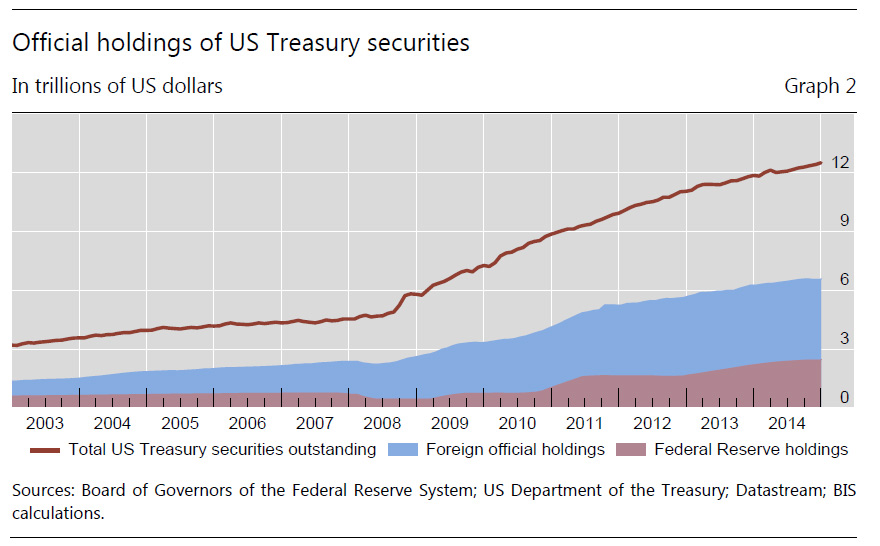

An array of possibilities then presents itself in terms of the depth of international policy cooperation, ranging from extended local rules to new global rules of the game. To extend local rules, major central banks could internalise spillovers so as to contain the risk of financial imbalances building up to the point of blowing back on their domestic economies. Incorporating spillovers in monetary policy setting may improve performance over the medium term. This approach is thus fully consistent with enlightened self-interest. The need for policymakers to pay attention to global effects can be seen clearly in the major bond markets. Official reserve managers and major central banks hold large portions of outstanding government debt.

If investors treat bonds denominated in different currencies as close substitutes, central bank purchases that lower yields in one bond market also weigh on yields in other markets. For many years, changes in US bond yields have been thought to move yields abroad; in the last year, many observers have ascribed lower global bond yields to the ECB’s consideration of and implementation of large-scale bond purchases. Central banks ought to take account of these effects when setting monetary policy. However, even if countries do optimise their own domestic policies with full information, a global optimum cannot be reached when there are externalities and strategic complementarities as in today’s era of global liquidity. This means that we will also need more international cooperation. This could mean taking ad hoc joint action, or perhaps even developing new global rules of the game to help instil additional discipline in national policies. Given the pre-eminence of the key international currencies, the major central banks have a special responsibility to conduct policy in a way that supports global financial stability – a way that keeps the neighbourhood in order.

Importantly, the domestic focus of central bank mandates need not preclude progress in this direction. After all, national mandates in bank regulation and supervision have also permitted extensive international cooperation and the development of global principles and standards in this area.

Conclusion

To conclude, the current environment offers us a good opportunity to revisit the various issues regarding the IMFS. Addressing the blind spot in the system will require us to take a global view. We need to better anchor domestic policies by taking financial factors into account. We also need to understand and internalise the international spillovers and interactions of policies. This new approach will pose challenges. We have yet to develop an analytical framework that allows us to properly integrate financial factors – including international spillovers – into monetary policy. And there is work to be done to enhance international cooperation. All these elements together would help establish better global rules of the game.

The global financial crisis has demonstrated that international cooperation in crisis management can be effective. For instance, the establishment of international central bank swap lines can be seen as an example of enlightened self-interest. However, we must also recognise that there are limits to how far and how fast the global safety nets can be extended to mitigate future strains. This puts a premium on crisis prevention. Each country will need to do its part and contribute to making the global financial system more resilient – and I would add here that reinforcing the capacity of the IMF is one element in this regard. And taking international spillovers and financial stability issues into account in setting monetary policy is a useful step in this direction.