The international reform agenda has focussed on four broad objectives:

- building resilient financial firms (particularly banks);

- ending too-big-to-fail;

- transforming shadow banking into transparent and resilient market-based financing; and

- making derivative markets safer.

When we look at each of these areas, I am confident that most people in this room would agree with the broad conclusion that a great deal of work has been done, and that in all cases we are better off today than we were pre-2007. But I suspect many of you would also hold to the view that there is more to do before we can genuinely sit back and say the job is done.

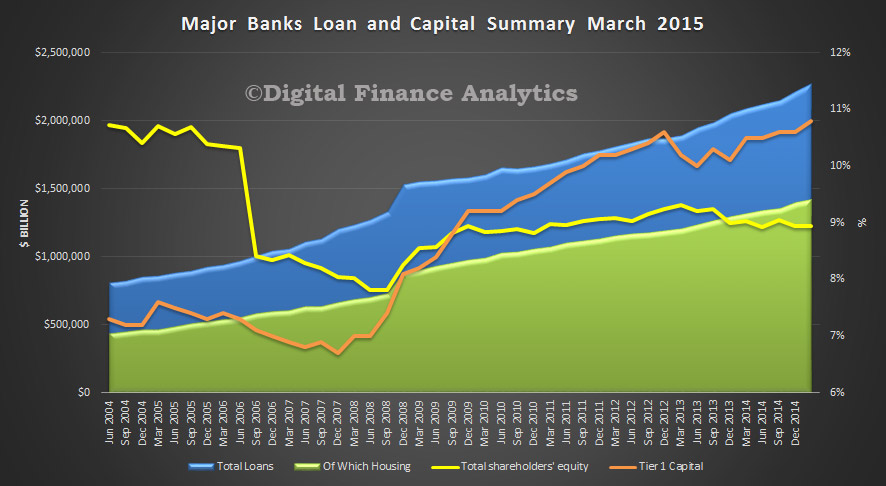

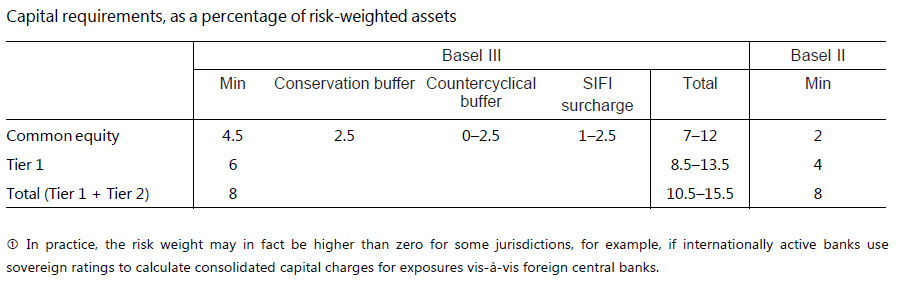

Let’s start with bank capital and liquidity. Basel III substantially increased the quality and quantity of bank capital and, just as importantly, introduced new standards for liquidity and funding where there had previously been an international void. Even though many of these new standards are not required to be fully in place for a few years yet, we can look at the banking industry today and say that, by and large, the industry is meeting the new standards with:

- substantial amounts of new equity having been raised;

- capital instruments that did not act as a loss absorber being replaced;

- greater levels of liquidity, and (more importantly) better liquidity management evident; and

- excessive structural maturity mismatches being contained to more prudent levels.

All of this has been achieved without, as was predicted by some when the reforms were announced, the sky falling in. Indeed, resilience has become a virtue for financial firms, and critical to being a strong competitor in financial markets. Long may that continue.

Critical to making sure this is not a temporary phenomenon has been consistent implementation of the Basel III standards into national regulations. One of the more important post-crisis reforms that does not always get the credit it deserves is the decision by member jurisdictions to open themselves up to a much greater level of peer review. The Basel Committee’s Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP) has been instrumental in demonstrating to the world that the G20’s commitment to the full, timely and consistent implementation of Basel III was serious – and it has placed the spotlight on areas where it has not yet been delivered. Having been intimately involved in the first dozen or so of these reviews, I can confidently say they have had an unambiguously positive impact. Similar peer review programmes by the FSB and other standard-setters have provided additional scrutiny and transparency to national implementation in a range of other areas.

The important point to note is that, when we think about post-crisis reforms, it is not just financial firms that have needed to lift their game; regulatory agencies have needed to do likewise.

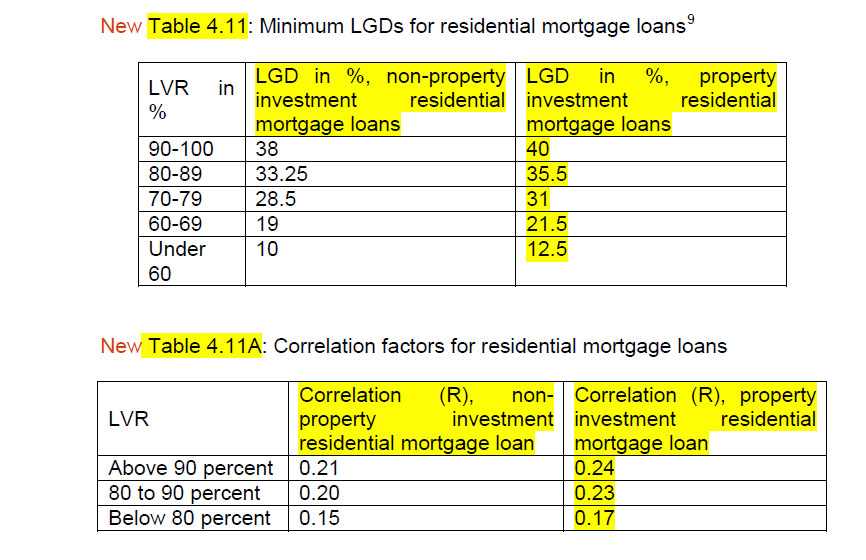

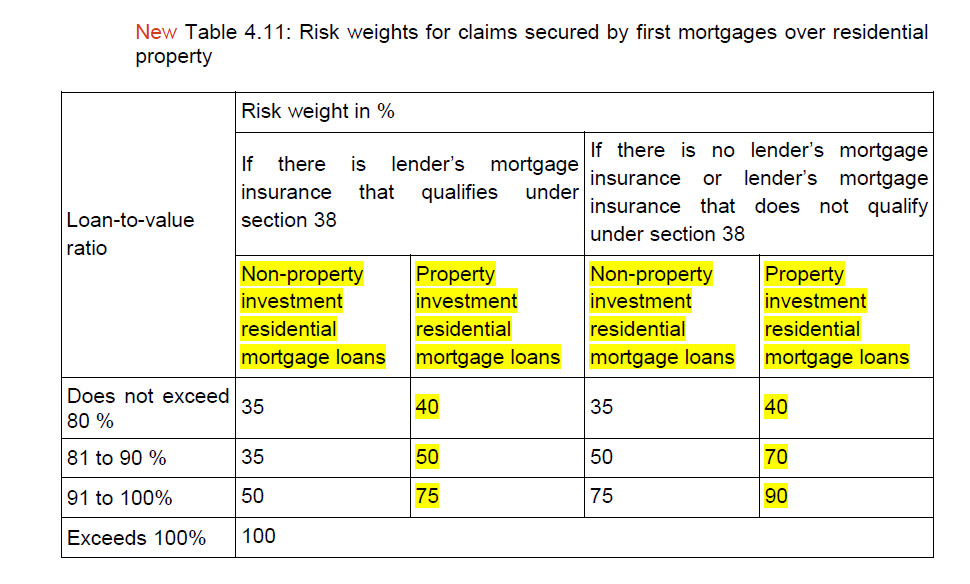

There is still more to do, and the Basel Committee’s upcoming meeting has a busy agenda. If I have a reservation when it comes to the remaining policy work programme of the Committee, it is that the finish line still looks a little too far away in some key areas. We may be better off if we narrow our focus and devote our resources to a few key issues – which I would argue centre on the IRB approach and the reliability of models in the regulatory framework – and make sure we deal with them as quickly as possible. That doesn’t mean we should not address the full range of remaining issues on the agenda, but the need for immediate action is much less.

Too-big-to-fail has been a long-standing problem; almost by definition, long-standing problems don’t have an easy answer. Nevertheless, measures that reduce implicit subsidies and price risk correctly should substantially improve the resilience, efficiency and competitiveness of the financial system, so our efforts are undoubtedly adding value. And we have made good headway. Regimes for identifying and applying higher capital requirements for G- and D-SIBs (and soon G-SIIs), more robust resolution arrangements, the development of meaningful recovery plans that do not rely on public sector support, and current efforts to establish greater loss-absorbing capacity in the world’s G-SIBs will not necessarily rid the world completely of the too-big-to-fail problem, but will lessen the difficulties that authorities face in times of stress. It is certainly a worthwhile investment to make.

When it comes to shadow banking and derivative reforms, we have made important progress in key areas, but the task is far from complete. In the case of shadow banking, we continue to grapple with understanding what exists in the shadows. The good news is that our knowledge is better than it was, and we are all alert to the risks, but we cannot yet feel confident that a concentration of risk could not be lurking undetected. The increased use of trade repositories and CCPs for derivatives markets has created a more transparent and orderly trading environment. But again, we have not yet done all we need to to get a good global picture of the risks in these markets.

That brings me to an important general observation. We have done better in implementing reforms where we have set international minimum standards, but allowed national regulators a degree of discretion to tailor the nature and timing of local requirements to local circumstances. A corollary of this is that we have tended to do better in implementing reforms that relate to financial firms than we have for reforms that relate to financial markets.

Some countries have gone faster and some slower on Basel III, some have introduced the minimum requirements and some have seen fit to do more, some have had to tailor the new requirements to fit with domestic legislative requirements, but generally speaking the new set of minimum standards have been implemented fairly uniformly around the globe (including by countries that are not members of the Basel Committee). The community of national regulators has been able to do this largely because there is scope, given their status as minimum international standards applying to individual firms, for a degree of domestic discretion. There are, if you like, safety values that mean domestic needs can be accommodated while at the same time preserving a common internationally‑agreed minimum. And, because they are applied to individual firms, the externalities that are imposed on other jurisdictions by any variations in implementation are fairly limited – provided, of course, the minimum standards are met.

Progress has been more difficult in areas where a much higher degree of cooperation or consistency is needed. International aspects of recovery and resolution planning, for example, are far less advanced than domestic aspects. It is even more evident when we look at many of the market-based standards. Today’s financial markets are global (or at very least highly inter-connected), and cannot work efficiently if they are subject to regulations that vary widely from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In other words, the externalities from inconsistent implementation are much greater. A coherent and consistent regulatory regime – critical to limiting opportunities for arbitrage and the tendency for activity to flow to the weakest regulatory environment – requires us all to look beyond our domestic bases, but this has at times proven difficult.

There is no simple solution to this, beyond a recognition that we need to redouble our efforts towards cooperation for the global good. We cannot get away from the fact we are national regulators, with domestic mandates. Where taxpayer funds are ultimately at risk, it is difficult to expect otherwise. But all is not lost because, in an increasingly inter-connected world, domestic interests and the global common good are often quite well aligned. And we have to remember that we all lose if sound economic activity is significantly impeded.

Before I conclude, I would like to highlight two areas where I think we have not yet done anywhere near enough to address the shortcomings that the financial crisis highlighted.

The first is in the supervision of financial firms. We have done a great deal to strengthen the regulatory framework within which financial firms operate. We cannot, however, hope to achieve financial stability, and resilience in individual firms, with just a rulebook.

Whatever type of football you follow, you would not ask two professional football teams to adjudicate a match by themselves. Even though all the players may know the rulebook very well, their competitive instincts mean that without on-field officials, the temptation to break the rules would likely be too great. Any such a game is likely to quickly degenerate into chaos.

Good match officials are critical to an attractive match. They keep the game flowing, their presence acts as reminder to players to play within the rules, and they will sometimes be able to head off infringements before they occur. When needed, they will ensure transgressions are detected and penalised. Good supervisors play a similar role in the financial system – the game is better for the participants and the spectators when high quality officials are monitoring the play.

I do not think we have yet invested enough in promoting good supervision. Indeed, the immediate post-crisis period seemed to start with a philosophy that we should have less supervision and more rules. The strengthened rules were absolutely essential, but they will not be effective in the long run without being supplemented by strong and robust supervision. Our approach is Australia is not to consider supervisors as a means of enforcing regulation, but rather regulation as a means of empowering good supervision. But this philosophy is not universally held, and I think the system is weaker for it.

The second area that we still have room to make serious improvement is in the inter-related areas of governance, culture and remuneration. Building up capital and liquidity, and ensuring loss absorbing capacity in the event of failure, will undoubtedly make for a more resilient financial system. But they will only offer a partial remedy to the problems that were experienced unless there are behavioural changes within financial firms as well.

Culture is a nebulous concept, much more difficult to define and observe than capital adequacy. But strengthening culture, like strengthening capital, is critical to long-run stability. We regularly see instances where participants in financial markets, when faced with an ethical dilemma, fail to ask themselves ‘is this right?’ Instead, the question has often been ‘can I get away with this?’ – or, more ominously, in some cases it appears no question was asked because the attitude was ‘if you ain’t cheating, you ain’t trying’. For an industry that is ultimately founded on trust, something serious is amiss, and strong and ethical leadership within financial firms is needed to set this right.

Both the industry, and the community of supervisors, is still grappling with how best to make assessments of organisational culture, and how to respond when a culture is shown to be in need of improvement. Much has to do with the incentives that individuals face and how they signal what an organisation truly values (and what it does not). It is clear that, in many cases, aspirational statements of organisational culture have been no match for the personal incentives that are created for individuals. Much of the post-crisis reform agenda has been aimed at getting the organisational interests of financial firms more aligned with those of the wider community. Getting personal incentives correspondingly aligned with organisational interests needs to be seen as equally important. On this, we all have more to do.