Australia’s Financial System Inquiry (FSI), due to report by end-2014, is likely to recommend higher capital requirements for the large banks, says Fitch Ratings. A higher capital charge and/or a rise to the mortgage risk-weighting floor for the four domestic systemically important banks (D-SIBs) are the most likely ways in which this will be implemented. In either case, Fitch maintains that Australia’s banks are well positioned to meet the additional buffers though internal capital generation.

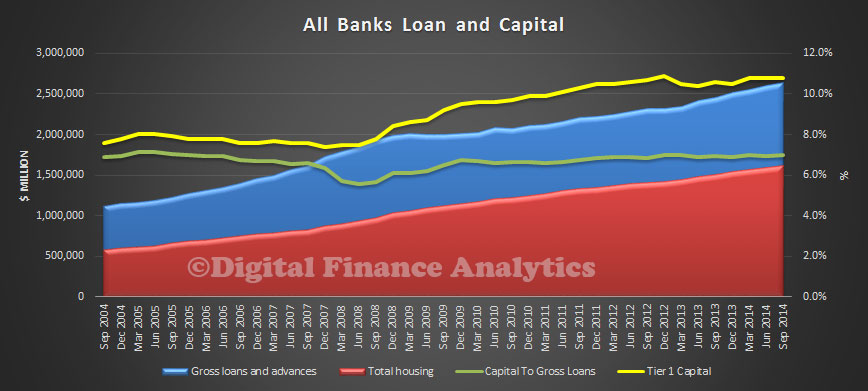

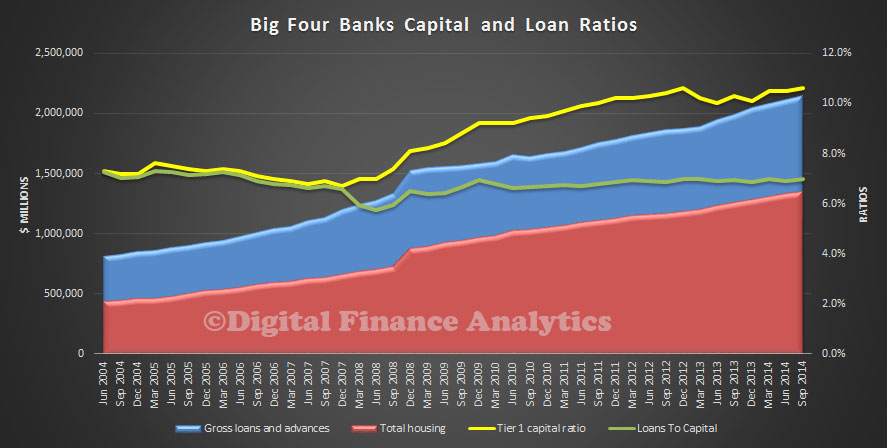

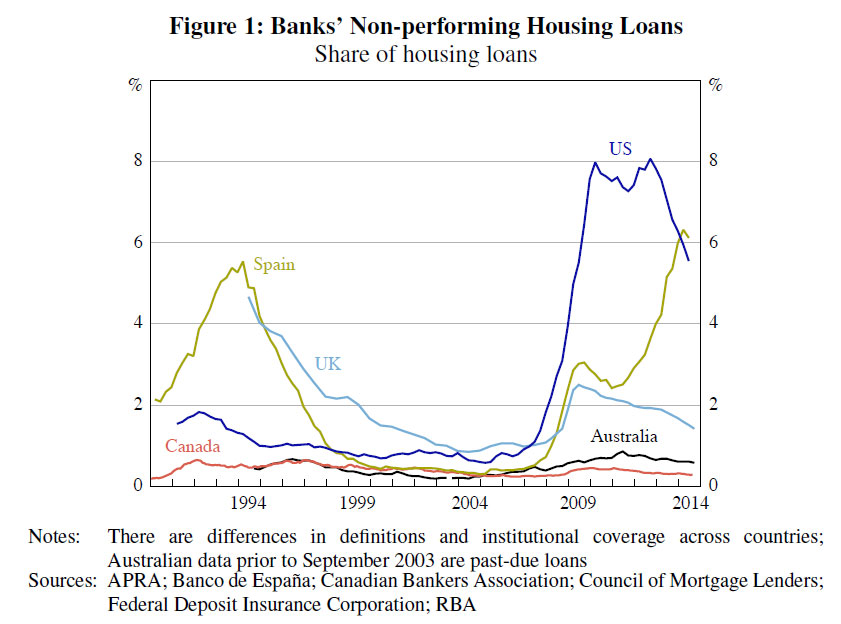

Australia’s bank capital profiles have strengthened since 2008, though they are about average relative to their international peers. Fitch maintains that additional capital requirements for the four D-SIBs – ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac – would be credit positive.

The FSI, led by Chairman David Murray, is expected to push for regulatory changes that would reinforce the improvements in recent years. The gap between Australia’s banks and global peers in terms of capital strength has closed, though an objective of the FSI is to bring the largest banks back into the upper quartile. Increasing the D-SIB capital buffer requirement from the current 1ppt, as well as implementing a mortgage risk-weight floor for banks using advanced models to calculate regulatory capital, are likely to be two areas of focus for the Murray report.

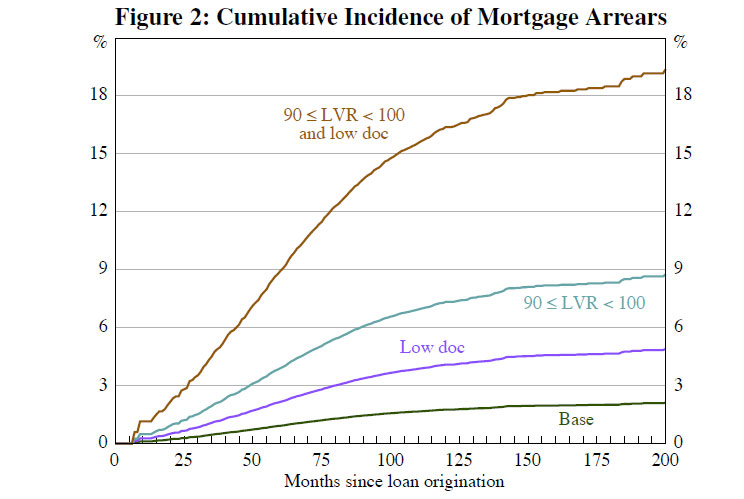

A number of global initiatives are addressing the wide discrepancy in risk weights based on banks’ internal models, including a Basel Committee project. Risk-weights for residential mortgages have been a particular focus because they can be very low. In Sweden, the risk-weight floor for residential mortgages was raised to 25% from 15% this year, while Norway is raising its floor to 20%-25% from 10%-20%. In Switzerland, the authorities are reviewing the differences between risk-weights based on banks’ internal models and those based on the standard approach used by domestic and regional banks.

Taking the global context into account, there is the potential for the FSI to recommend raising Australia’s mortgage risk-weight floor to 25%, which would result in capital shortfalls for each of the four major banks – AUD2.9bn for ANZ (the lowest) to in excess of AUD4.6bn for Westpac, based on FY14 numbers and assuming the banks maintain an internal buffer of 1ppt over the fully loaded regulatory requirements. Under a more aggressive scenario, where the risk-weight floor is increased to 30%, the D-SIB charge also raised 2ppt to 3ppt, and a 1ppt internal buffer maintained, the capital shortfalls would be between AUD12bn-15bn for each of the Big 4, and total around AUD53bn. With combined profits for the four banks of around AUD29bn in FY14, the capital shortfall under this scenario would be just less than twice annual profit before dividend.

The Basel Committee’s framework for D-SIBs is more flexible and less prescriptive than the G-SIB framework that applies to the world’s largest banks, but the phase-in for both starts in 2016. Few jurisdictions have yet finalised their D-SIB implementation, but the current 1ppt requirement in Australia appears low compared with Sweden, where a systemic risk buffer of 3ppt is required from 1 January 2015, with a further 2ppt within Pillar 2. Hong Kong, Singapore and India are considering D-SIB buffers of up to 2.5ppt, 2.0ppt and 0.8ppt, respectively, although these have not necessarily been finalised.

Fitch expects that the Australian authorities would set implementation timetables so that the banks would be able to generate the bulk of capital internally, even under the latter scenario.

Increasing the capital of the Big 4 would continue the trend for credit profile strengthening that has occurred since 2008 at a time when there are concerns about risks from rising property prices and exposure to a slowing China and commodity cycle. However, competitively, the higher D-SIB charges and risk-weight floors for the Big 4 could erode some of their substantial scale advantages relative to smaller competitors.

It is important to note that if the measures to address the problems of ‘too big to fail’ banks went beyond higher capital requirements and included measures such as ‘bail-in’ of senior creditors, this would be likely to result in downgrades of Fitch’s Support Ratings and Support Rating Floors – the agency currently factors in a very high likelihood of government support for the major banks, given their strong market position in the domestic banking system. The Issuer Default Ratings, however, would be unaffected, as no Australian bank is currently at its Support Rating Floor.