The end of the year is always a time when there are currency and liquidity issues in China. This has to do with things like taxes being paid, and bonuses for workers etc. So it’s not a great surprise that the same happens in 2016 too. Then again, the overnight repo rate of 33% on Tuesday was not exactly normal. That indicates something like a black ice interbank market, things that can get costly fast.

I found it amusing to see Bloomberg report that: “As banks become more reluctant to offer cash to other types of institutions, the latter have to turn to the exchange for money, said Xu Hanfei at Guotai Junan Securities in Shanghai. Amusing, because I bet many will instead have turned to the shadow banking system for relief. So much of China’s financial wherewithal is linked to ‘the shadows’ these days, it would make sense for Beijing to bring more of it out into the light of day. Don’t hold your breath.

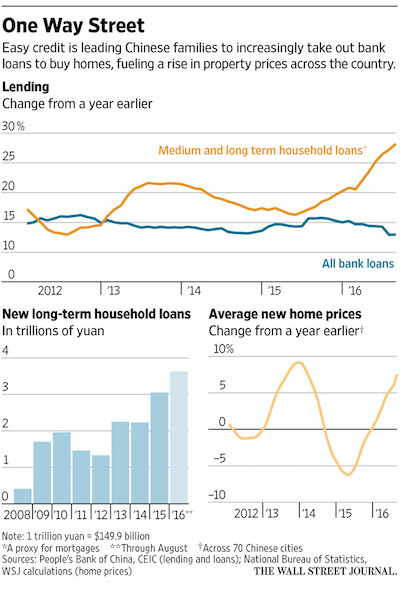

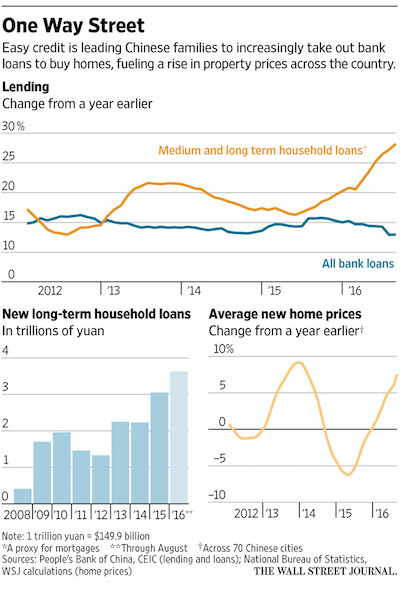

Tyler on last night’s situation: ..the government crackdown on the credit and housing bubble may be serious for once due to fears about “rising social tensions”, much of the overnight repo rate spike was driven by the PBOC which pulled a net 150 billion yuan of funds in open-market operations..”. And the graph that comes with it:

It all sounds reasonable and explicable, though I’m not sure ‘core leader’ Xi would really want to come down hard on housing -he certainly hasn’t so far-, but there are things that do warrant additional attention. The first has to be that on Sunday January 1 2017, a ‘new round’ of $50,000 per capita permissions to convert yuan into foreign currencies comes into effect. And a lot of Chinese people are set to want to make use of that, fast.

Because there is a lot of talk and a lot of rumors about an impending devaluation. That’s not so strange given the continuing news about increasing outflows and shrinking foreign reserves. And those $50,000 is just the permitted amount. Beyond that, things like real estate purchases abroad, and ‘insurance policies’ bought in Hong Kong, add a lot to the total.

What makes this interesting is that if only 1% of the Chinese population -close to 1.4 billion people- would want to make use of these conversion quota, and most of them would clamor for US dollars, certainly since its post-election rise, if just 1% did that, 14 million times $50,000, or $700 billion, would potentially be converted from yuan to USD. That’s almost 20% of the foreign reserves China has left ($3.12 trillion in October, from $4 trillion in June 2014).

In other words, a blood letting. And of course this is painting with a broad stroke, and it’s hypothetical, but it’s not completely nuts either: it’s just 1% of the people. Make it 2%, and why not, and you’re talking close to 40% of foreign reserves. This means that the devaluation rumors should not be taken too lightly. If things go only a little against Beijing, devaluation may become inevitable soon.

In that regard, a remarkable change seems to be that while China’s always been intent on keeping foreign investment out, now all of a sudden they announce they’re going to sharply reduce restrictions on foreign investment access in 2017. While at the same time restricting mergers and acquisitions by Chinese corporations abroad, in an attempt to keep -more- money from flowing out. Something that has been as unsuccessful as so many other pledges.

The yuan has declined 6.6% in value in 2016 (and 15% since mid-2014), and that’s probably as bad as it gets before some people start calling it an outright devaluation. More downward pressure is certain, through the conversion quota mentioned before. After that, first there’s Trump’s January 20 inauguration, and a week after, on January 27, Chinese Lunar New Year begins.

May you live in exciting times indeed. It might be a busy week in Beijing. As AFP reported at the beginning of December:

Trump has vowed to formally declare China a “currency manipulator” on the first day of his presidency, which would oblige the US Treasury to open negotiations with Beijing on allowing the renminbi to rise.

Sounds good and reasonable too, but how exactly would China go about “allowing the renminbi to rise”? It’s the last thing the currency is inclined to do right now. It would appear it would take very strict capital controls to stop the currency from plunging, and that’s about the last thing Xi is waiting for. For one thing, the hard-fought inclusion in the IMF basket would come under pressure as well. AFP continues:

China charges an average 15.6% tariff on US agricultural imports and 9% on other goods, according to the WTO.

Chinese farm products pay 4.4% and other goods 3.6% when coming into the United States.

China is the United States’ largest trading partner, but America ran a $366 billion deficit with Beijing in goods and services in 2015, up 6.6% on the year before.

I don’t know about you, but I think I can see where Trump is coming from. Opinions may differ, but those tariff differences look as if they belong to another era, as in the era they came from, years ago. Lots of water through the Three Gorges since then. So the first thing the US Treasury will suggest to China on the first available and convenient occasion after January 20 for their legally obligatory talk is: let’s equalize this. What you charge us, we’ll charge you. Call it even and call it a day.

That would both make Chinese products considerably more expensive in the States, and open the Chinese economy to American competition. There are many hundreds of billions of dollars in trade involved. And of course I see all the voices claiming that it will hurt the US more than China and all that, but what would they suggest, then? You can’t leave this tariff gap in place forever, so what do you do?

I’m sure Trump and his team, Wilbur Ross et al, have been looking at this a lot, it’s a biggie, and have a schedule in their heads for phasing out the gap in multiple steps. Steps too steep and short for China, no doubt, but then, I don’t buy the argument that the US should sit still because China owns so much US debt. That’s a double-edged sword if ever there was one, and all hands on the table know it.

If you’re Xi, and you’re halfway realist, you just know that Trump will aim to cut the $366 billion 2015 deficit by at least 50% for 2017, and take it from there. That’s another big chunk of change the core leader stands to lose. And another major pressure point for the yuan, obviously. How Xi would want to avoid devaluation, I don’t know. How he would handle it once it can no longer be avoided, don’t know that either. Trump’s trump card?

One other change in China in 2016 warrants scrutiny. That is, the metamorphosis of many Chinese people from caterpillar savers into butterfly borrowers. Or gamblers, even. It’s one thing to buy units in empty apartment blocks with your savings, but it’s another to buy them with money you borrow. But then, many Chinese still have access to few other investment options. That’s why the $50,000 conversion to USD permission as per January 1 could grow real big.

But in the meantime, many have borrowed to buy real estate. And they’ve been buying into a genuine absolute bubble. It’s not always evident, because prices keep oscillating, but the last move in that wave will be down.

If I were Xi, all these things would keep me up at night. But I’m not him, and I can’t oversee to what extent his mind is still in the ‘omnipotent sphere’, if he still has the impression that in the end, come what may, he’s in total control. In my view, his problem is that he has two bad choices to choose from.

Either he will have to devalue the yuan, and sharply too (to avoid a second round), an option that risks serious problems with Trump and other leaders (IMF), and would take away much of the wealth the Chinese people thought they had built up -ergo: social unrest-.

Either that or he will be forced, if he wants to maintain some stability in the yuan’s valuation, to clamp down domestically with very grave capital controls, which carries the all too obvious risk of, once again, serious social unrest. And which would (re-)isolate the country to such an extent that the entire economic model that lifted the country out of isolation in the first place would be at risk.

This may play out relatively quickly, if for instance sufficient numbers of people (the 1% would do) try to convert their $50,000 allotment of yuan into dollars -and the government is forced to say it doesn’t have enough dollars-. But that is hard to oversee from the outside.

There are, for me, too many ‘unknown unknowns’ in this game. But I don’t see it, I don’t see how Xi and his crew will get themselves through this minefield without getting burned. I’m looking for an escape route, but there seem to be none available. Only hard choices. If you come upon a fork in the road, China, don’t take it.

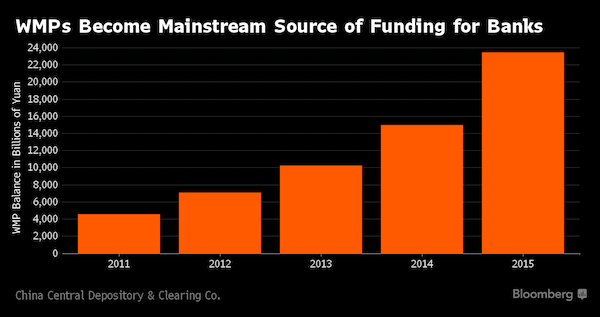

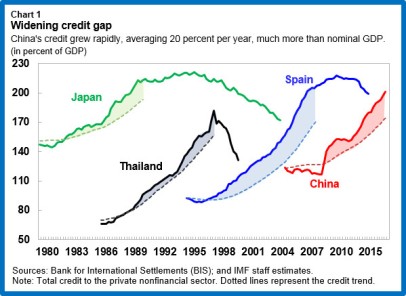

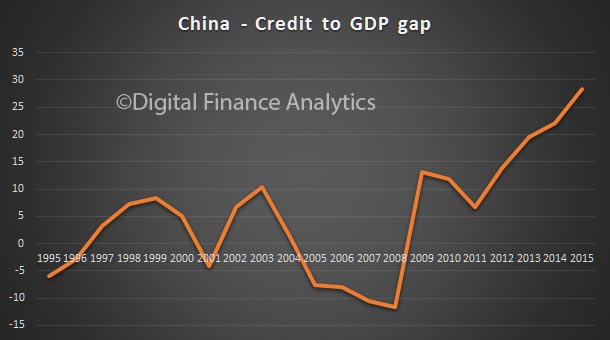

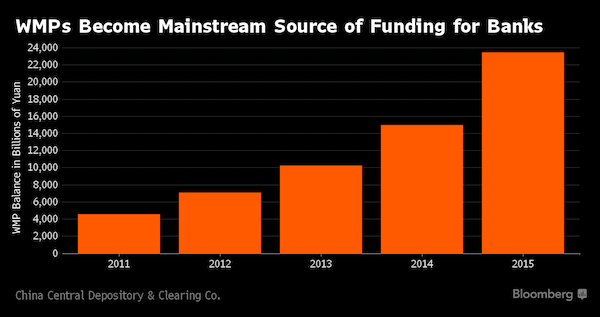

And mind you, this is all without even having touched upon the massive debts incurred by thousands upon thousands of local governments, and the grip that these debts have allowed the shadow banks to get on society, without mentioning the Wealth Management Products and other vehicles in that part of the economy, another ‘industry’ worth trillions of dollars. I mean, just look at the growth rates in these instruments:

There’s simply too much debt all throughout the system, and it’s due for a behemoth restructuring. You look at some of the numbers and graphs, and you wonder: what were they thinking?