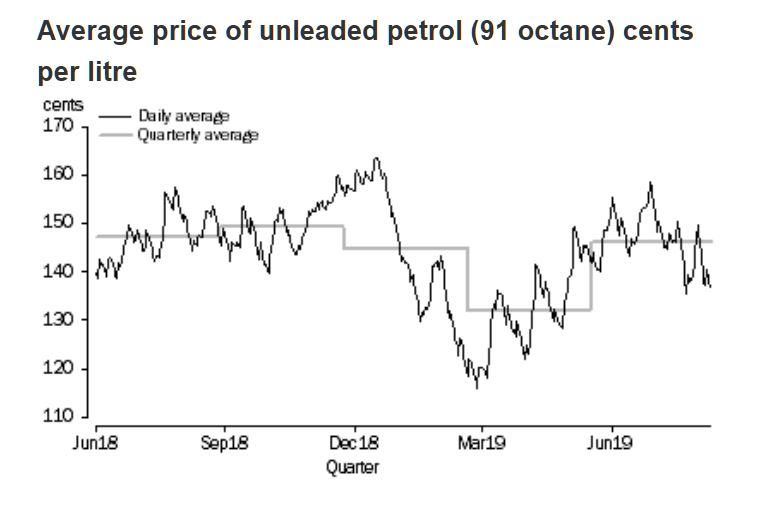

The annual average retail petrol price in 2018–19 was the highest in real terms (i.e. adjusted for inflation) in four years according to the ACCC’s latest report on the Australian petroleum market for June quarter 2019.

The report shows that in the five largest cities, Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, the average annual petrol price in 2018–19 was 141.2 cents per litre (cpl), nearly 7.0 cpl higher than last year. In nominal terms (i.e. with prices not adjusted for inflation) it was the highest annual average price in five years.

Annual average retail petrol prices in the five largest cities in nominal and real terms: 2000–01 to 2018–19

“The most significant contributor to this increase was the depreciation over the year in the AUD-USD exchange rate, which decreased by USD 0.06 to USD 0.72,” said ACCC Chair Rod Sims.

“This was the lowest annual average AUD-USD exchange rate in the last 15 years. The AUD–USD exchange rate is a significant determinant of Australia’s retail petrol prices because international refined petrol is bought and sold in US dollars in global markets.”

A significant development in the petrol industry in the first half of 2019 has been the change in price setter at both Coles Express, to Viva Energy, and Woolworths, to EG Group, retail sites.

The report found that compared with market average prices, Coles Express prices were lower in most capital cities after Viva Energy began setting prices. However, they remained above the market average price in all eight capital cities. At Woolworths, prices were higher in most capital cities after EG Group took over the retail sites, although in the majority of cities, prices were still below the market average price.

“The ACCC will monitor prices at these retail sites very closely in future,” Mr Sims said.

Mr Sims said it was important for motorists to shop around for cheap fuel by using the available fuel price websites and apps. For those motorists in the five largest cities, they can also use information about petrol price cycles on the ACCC website to time their purchases.

Retail petrol prices in the three smaller capital cities; Canberra, Hobart and Darwin, are typically higher than prices in the five largest cities. However, the report noted that, in the first half of 2019, there were periods when prices in Darwin and Canberra were below prices in the five largest cities.

Monthly average retail prices in Darwin were lower than in the five largest cities between February and May 2019, and monthly average retail prices in Canberra were lower than in the five largest cities in both April and May 2019.

“This was the first time monthly average prices in Canberra were below the average price in the five largest cities since April 2012,” Mr Sims said. “The reduction in prices in the Darwin and Canberra is good news for motorists in those locations.”

The lower prices in Canberra may have been influenced by the possibility of greater regulation of the petroleum industry arising from the current ACT Legislative Assembly petrol inquiry. The situation in Canberra is similar to that in Darwin in 2015, when the decrease in petrol prices coincided with increased local scrutiny of petrol prices by the NT Government.

The report noted that in the June quarter 2019, average retail petrol prices across the five largest cities were 145.3 cpl, an increase of 15.0 cpl from the March quarter 2019. The principal driver of the increase was rising international crude oil and refined petrol prices in the quarter. These continue to be influenced by the agreements made since late-2016 by the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cartel, and some other crude oil producing countries, including Russia, to cut production.

Other petrol fast facts:

- Brisbane petrol prices were higher than the other large Australian cities.

- The city–country petrol price differential decreased in the quarter to 1.5 cpl.

- Analysis of NSW’s Coffs Harbour petrol prices shows there are a range of prices available to motorists if they shop around.

- Diesel and automotive LPG prices in the five largest cities both increased.