“Where consumers see a card surcharge, they should check to see what non-surcharged methods of payment are available. Before paying a surcharge, they should think about whether any benefits from using that payment method outweigh the cost of the surcharge; if not they should consider switching to an alternative payment method. This will not only save them money, it will help keep costs down for businesses and will put pressure on card schemes to keep their charges low”. This was Tony Richards, 26th Annual Credit Law Conference and discussed the revised card payment surcharging regime.

In his speech he started by looking at data on average merchant service fees (or MSFs) show that there are very large differences in the cost of different card systems for merchants. These costs ranged from an average of just 0.14 per cent of transaction value for eftpos in the June quarter to about 2 per cent of transaction value for Diners Club. For MasterCard and Visa transactions, the average cost to merchants of debit cards was 0.55 per cent of transaction value, while the average cost of credit card transactions was 0.81 per cent. The average cost of American Express cards was 1.66 per cent of transaction value.

But these averages mask significant variation across different merchants. Many merchants pay up to 1–1½ per cent on average for MasterCard and Visa credit card transactions. And it is not unusual for merchants to pay 2–3 per cent to receive an American Express card payment.

Then he discussed five key elements of the new framework contained in the Bank’s new surcharging standard and the Government’s amendments to the Competition and Consumer Act.

First, the new framework preserves the right of merchants to surcharge for more expensive cards, but it does not require them to do so. Under the framework, a merchant that decides to surcharge a particular type of card may not surcharge above their average cost of acceptance for that card type.

For example, if on average it costs a merchant 1 per cent of the value of a transaction to receive a Visa credit card payment, the merchant may apply a surcharge of up to 1 per cent for that type of card. The merchant would not, however, be able to apply the same 1 per cent surcharge if the customer chose instead to pay with a debit card that was less costly to the merchant.

Second, the definition of card acceptance costs that can be included in a card surcharge has been narrowed. Acceptable costs will be limited to fees paid to the merchant’s card acquirer (or other payments facilitator) and a limited number of other documented costs paid to third parties for services directly related to accepting the particular type of card. A merchant’s internal costs cannot be included in a surcharge.

Third, a merchant that wishes to surcharge will typically have to do so in percentage terms rather than as a fixed-dollar amount. In the airline industry, this means that surcharges on lower-value airfares have been reduced significantly.

Fourth, the Government has given the ACCC investigation and enforcement powers over cases of possible excessive surcharging.

The Bank’s standard and the ACCC’s enforcement powers apply to payment surcharges in six card systems that have been designated by the Reserve Bank – eftpos, the MasterCard debit and credit systems, Visa’s debit and credit systems, and the American Express companion card system. However, Reserve Bank staff have been in discussions with other card systems that have not been designated and we expect that those systems will all be including conditions in their merchant agreements that are similar to the limits on surcharges under the Bank’s standard. This will mean that merchants that wish to surcharge on payments in these other systems will be contractually bound to similar surcharging caps to those that apply to the regulated systems.

Fifth, surcharging in the taxi industry – which is subject to significant regulation in many other aspects – will remain the responsibility of state taxi regulators. Until recently, surcharges of 10 per cent were typical in that industry. However, authorities in five of the eight states and territories have now taken decisions to limit surcharges to no more than 5 per cent. As new payment methods and technologies emerge, the Bank expects that it will be appropriate for caps on surcharges to be reduced below 5 per cent. The Government and the Bank will continue to monitor developments in the taxi industry with a view to assessing whether further measures are appropriate.

The first stage of implementation of the surcharging reforms took effect on 1 September and covers surcharging of card payments by large merchants. Merchants are defined as large if they meet certain tests in terms of their consolidated turnover, balance-sheet size or number of employees. The framework will take effect for other, smaller merchants in September 2017.

There are a few reasons for the delayed implementation for smaller merchants. Most importantly, these merchants are less likely to have a detailed understanding of their payment costs. Since the new framework involves enforcement by the ACCC, the Bank considered it important to ensure that such merchants have simple, easy-to-understand monthly and annual statements that show their average payment costs for each of the card systems subject to the Bank’s standard. Accordingly, as part of the new regulatory framework, acquirers and other payment providers must provide merchants with such statements by mid 2017. All merchants will be required to comply with the new surcharging framework from September 2017 and ACCC enforcement will apply also to smaller merchants from that point.

Given the new framework has only been effective for two weeks, it is too early to be definitive about how the new surcharging regime applying to large merchants has affected the surcharging behaviour of those merchants. However, based on some corporate announcements and an initial survey of some websites, I think it is possible to make six initial observations.

First, and most prominently, the major domestic airlines have moved away from fixed-dollar surcharges to percentage-based surcharging. This will result in a very significant reduction in surcharges payable on lower-value airfares. The two full-service airlines have introduced surcharges for on-line payments of 1.3 per cent for credit cards and 0.6 per cent for debit cards. A passenger wishing to pay for a $100 domestic airfare by card will now pay a surcharge of $1.30 or 60 cents, as opposed to a surcharge of up to $7-8 previously. Surcharges on some high-value airfares may rise with the shift to percentage-based surcharges. However, the airlines have implemented caps on surcharges of $11 for domestic fares and $70 for international fares, indicating that they continue to prefer to not pass on their full payment costs on purchases of more expensive tickets.

Second, there does not appear to have been any increase in the prevalence of surcharging. It remains the case that companies that face relatively low merchant service fees are tending not to surcharge, while those businesses which receive a high proportion of expensive cards are more likely to surcharge.

Third, the surcharge rates for credit cards that have been announced show significant variation, which is consistent with other evidence that there is a lot of variation in the merchant service fees faced by different businesses. In the case of the Qantas group, for example, Qantas is charging a credit card surcharge of 1.3 per cent while Jetstar – which presumably receives fewer high-cost cards – is charging a surcharge of 1.06 per cent.

Fourth, as required by the Australian Consumer Law, merchants that have announced changes to their surcharges are continuing to offer non-surcharged means of payment. In the face-to-face environment, this typically includes cash, eftpos and sometimes MasterCard and Visa debit cards. In the on-line environment, it typically includes payments via BPAY, POLi or direct debit, which are typically low-cost for merchants.

Fifth, while there are still many instances of ‘blended’ credit card surcharges, there are some early signs of greater discrimination in surcharges. Blending refers to the practice of charging the same surcharge across a number of systems regardless of their cost – say across the MasterCard, Visa and American Express credit systems.

The new framework allows merchants to set the same surcharge for a number of different payment systems, provided that the surcharge is no greater than the average cost of acceptance of the lowest-cost of those systems. For example, if a merchant accepts cards from two credit card systems, which have average costs of acceptance of 1 per cent and 1.5 per cent, it can set separate surcharges of up to 1 per cent and 1.5 per cent, respectively. If it wishes to set a single surcharge, it cannot average the costs and set a 1.25 per cent surcharge for both systems, since it would be surcharging one of those systems excessively. In this example, the maximum common surcharge that could be charged would be 1 per cent.

While I think we are already seeing some reduction in the practice of blended surcharging, it is likely that we will see this trend continue from mid 2017 when new rules on the interchange fees exchanged between banks for card transactions take effect. Without wishing to go into details, the Bank will for the first time be placing a cap on the maximum interchange fee that can be paid on any card transaction. This will significantly reduce the cost of MasterCard and Visa payments for those merchants which currently receive a high proportion of high-interchange cards.

The sixth change has been in the event ticketing industry, where it was previously very difficult to avoid a card surcharge in the on-line environment. Given this, the ACCC had already required the major ticketing companies to show their surcharges as a separate component within their headline, up-front pricing. Effective 1 September, the two major companies have now removed their card surcharges and are now quoting a simple, single price for all payment methods.

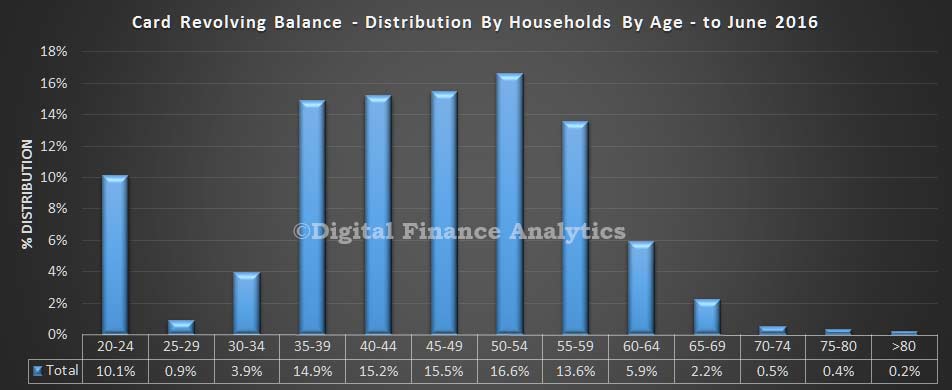

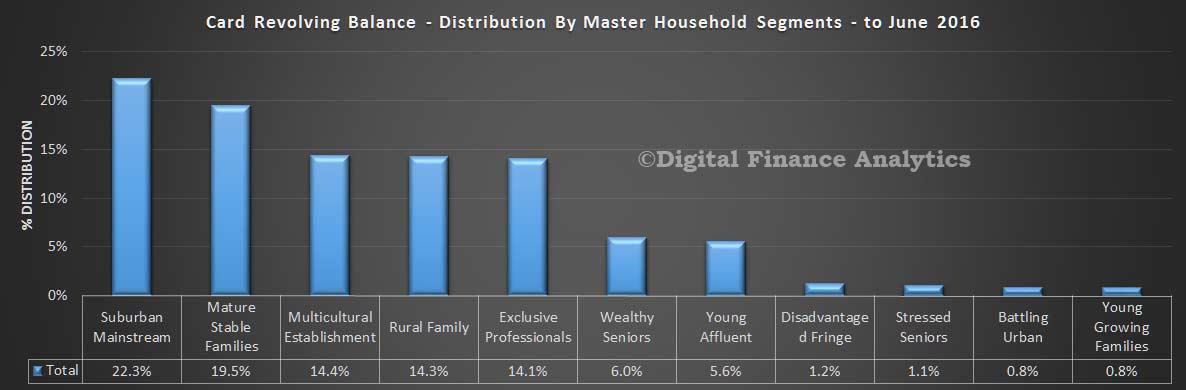

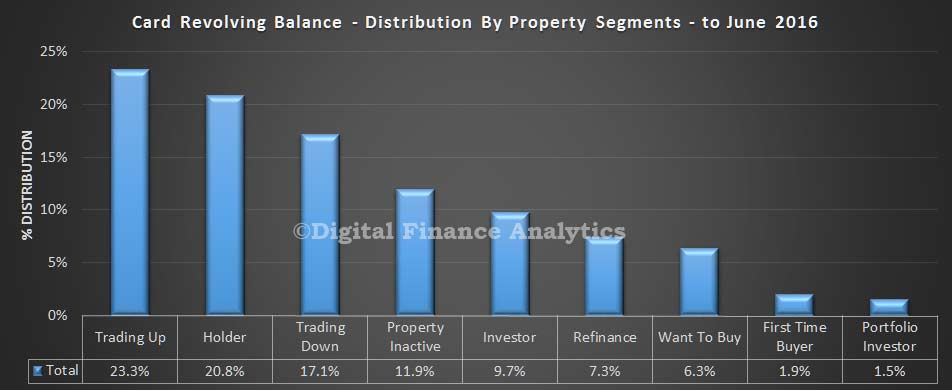

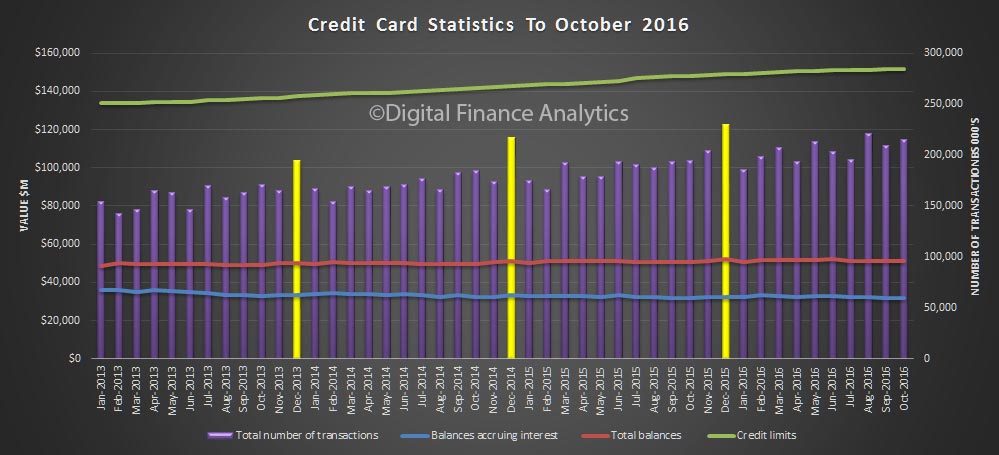

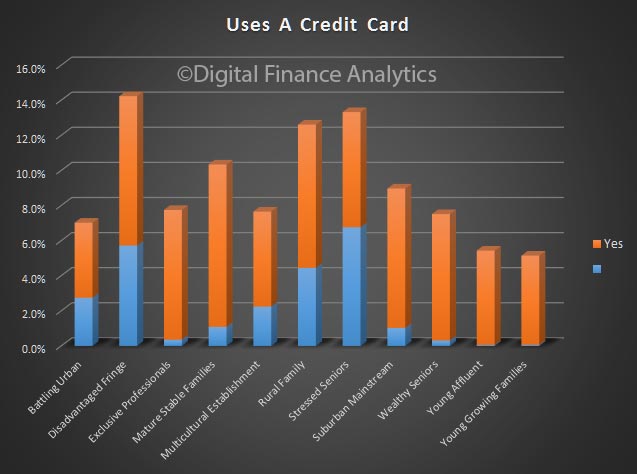

But card use varies by our household segments as used in our surveys.

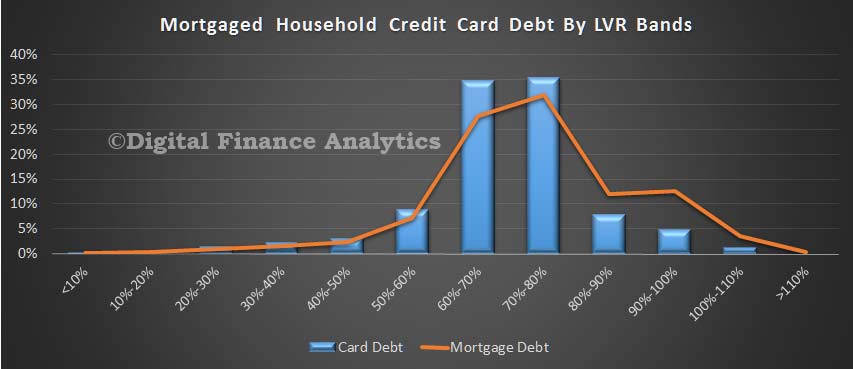

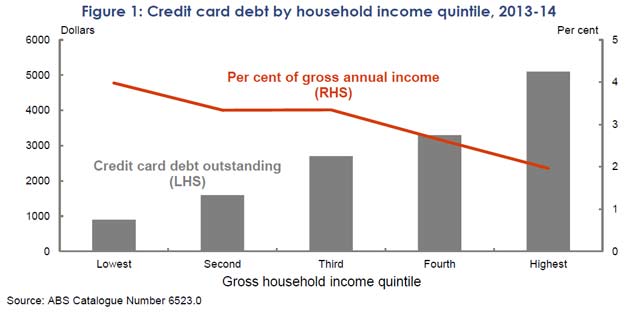

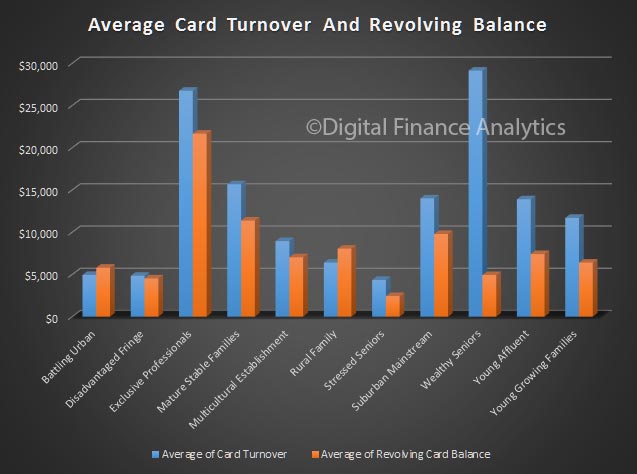

But card use varies by our household segments as used in our surveys. If we then overlay the average transaction turnover and revolving balances these also vary by segment. For examples, wealthy seniors use their cards and have high turnover balances, but revolve very little. On the other hand, exclusive professionals use their cards, and revolve significantly.

If we then overlay the average transaction turnover and revolving balances these also vary by segment. For examples, wealthy seniors use their cards and have high turnover balances, but revolve very little. On the other hand, exclusive professionals use their cards, and revolve significantly. This once again highlights the importance of customer segmentation within financial services. You can read more about our analysis of credit card economics here.

This once again highlights the importance of customer segmentation within financial services. You can read more about our analysis of credit card economics here.