The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

European Central Bank chief Christine Lagarde warned on Thursday that the coronavirus had delivered a “major shock” to the global economy that required urgent, coordinated action, as she unveiled fresh stimulus to keep credit flowing. Via France24

The latest major central bank to jump into the fray, the ECB launched a flurry of measures to cushion the impact of the virus, including increased bond purchases and cheap loans to banks.

But it surprised observers by leaving key interest rates unchanged.

The Paris and Frankfurt stock exchanges extended earlier losses after Lagarde‘s announcements to post drops of more than 10 percent in the early afternoon.

“The spread of the coronavirus COVID-19 has been a major shock to the growth prospects of the global economy and the euro area,” Lagarde told reporters in Frankfurt.

“Even if ultimately temporary by nature, it will have a significant impact on economic activity.”

She urged governments to step up and do their bit alongside monetary policymakers as fears mount of a credit crunch that could destabilise banks and hurt small businesses.

“Governments and all other policy institutions are called upon to take timely and targeted actions,” she said.

“In particular, an ambitious and coordinated fiscal policy response is required to support businesses and workers at risk.”

Whether the eurozone manages to avoid a recession will “clearly depend on the speed, the strength and the collective approach that will be taken by all players,” she said.

Super-cheap loans

As part of its stimulus package, the ECB’s governing council agreed a new round of cheap loans to banks, known as long-term refinancing operations (LTROs) “to provide immediate support to the euro area financial system”.

They also eased conditions on an existing “targeted” LTRO programme, aiming to “support bank lending to those affected most by the spread of the coronavirus, in particular small- and medium-sized enterprises”.

And the ECB will pile an extra 120 billion euros ($135 billion) of “quantitative easing” (QE) asset purchases this year on top of its present 20 billion per month.

The QE scheme will include “a strong contribution from the private sector,” the ECB said, as room to buy government debt while respecting self-imposed limits has grown tight.

On top of the monetary measures, the ECB’s banking supervision arm said it would allow banks to run down some of the capital buffers they must build up in good times to weather crises.

Its teams supervising individual lenders may provide more flexibility to institutions under their remit, such as giving them more time to patch up shortfalls in their risk management, while a broader range of assets will count towards the watchdog’s capital requirements.

‘Bravo’

Ahead of Thursday’s meeting, analysts had highlighted tweaks to the ECB’s bank lending scheme in particular as a critical tool for virus response.

“Bravo!” Pictet Wealth Management analyst Frederik Ducrozet tweeted after the statement, hailing the ECB’s “bold decisions”.

Ducrozet noted that under the changes to the TLTRO programme, lenders that loan the cash they get from the central bank on to the real economy will enjoy an interest rate potentially as low as -0.75 percent.

At 0.25 percentage points below the rate the ECB charges on banks’ deposits in Frankfurt, the difference represents an effective subsidy to the financial system.

Meanwhile the central bank dispensed with what many expected would be a purely symbolic interest rate cut of just 0.1 or 0.2 percentage points.

The US Federal Reserve last week and Bank of England on Tuesday had space to cut interest rates by half a percentage point each to ease financial conditions.

But the ECB’s already-negative deposit rate robbed it of that option.

Governments on hook

Lagarde again reiterated the ECB’s long-standing call on governments to do more with their fiscal powers to buttress the eurozone economy.

In a conference call Tuesday with European heads of government, the former International Monetary Fund (IMF) head “drew comparisons with past crises” like the 2008 financial crisis, a European source told AFP.

Such past trials were overcome by central banks and governments working in concert.

In mid-February, Lagarde reiterated that “monetary policy cannot, and should not, be the only game in town” to stimulate the economy.

Italy on Wednesday announced 25 billion euros of support to its economy and the European Union has also mobilised up to 25 billion euros.

Today we look at the recently confirmed merger talks between Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank. Will such a merger will really help to resolve the deep structural issues in the Eurozone?

Eurozone (EZ) GDP growth now looks likely to slow to just 1% this year according to a report published by Fitch Ratings‘ Economics team. The deterioration in growth prospects and declining inflation expectations will prompt the ECB to consider restarting asset purchases.

Economic activity data from the EZ has deteriorated more sharply than other parts of the world in recent months and has delivered the biggest negative surprise relative to market and Fitch’s own expectations.

“While numerous transitory factors are partly to blame, these cannot explain the breadth and depth of the slowdown. Rather, we believe that the slowdown has been primarily the result of deterioration in the external environment as net trade turned from a tailwind to a headwind,” said Fitch’s Chief Economist, Brian Coulton.

The domestic slowdown in China has, we believe, played a particularly important role here. Germany’s greater trade openness and larger exposure to China leave the largest European economy’s expansion more vulnerable to China’s domestic cycle and import demand. This is underlined by Germany having seen the biggest deterioration in activity data among the EZ economies – despite a healthy domestic economy with few of the imbalances that typically spark an abrupt downturn in domestic demand. Furthermore, the deterioration in manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Indices (PMIs) since last summer has been greatest in countries with a large auto export sector, dragged down by the first decline in global car sales since 2009 and the first fall in vehicle sales in China for several decades.

The weakening in EZ external indicators has not been matched in the domestic economy. Labour market performance remains strong supporting household income growth, monetary policy remains supportive, bank lending conditions are easy and credit to households and businesses continues to grow. Only in Italy have we seen evidence of private sector borrowers reporting somewhat tighter credit availability. Fiscal policy is also being eased in the EZ and should be supportive of growth in 2019. Private sector debt ratios have improved significantly since 2012 in Italy, Spain and Germany.

EZ growth should recover through the course of 2019 as the policy response in China helps to stabilise its economy from the middle of the year, one-off impediments to growth in Germany unwind, and EZ macro policy is eased. However, early indications for 1Q19 and the profile of our China forecast mean that there will not be much of a pick-up in EZ quarterly growth before 2H19.

This suggests that EZ growth in 2019 is likely to be around 1% compared with our December 2018 GEO forecast of 1.7%, a substantial cut. Both Germany and Italy will see similar revisions, with 2019 GDP growth now forecast at around 1% and 0.3% respectively. Even with this lower forecast, downside risks remain from an escalation in global trade tensions, a deeper slowdown in China, a disorderly no-deal Brexit or increased uncertainty related to domestic political tensions.

The sharp deterioration in growth prospects and falling inflation expectations are likely to result in renewed monetary stimulus measures from the ECB.

“We had already been expecting the ECB to delay the start of its policy normalisation -both interest rates and balance sheet reduction – but we now believe it will seriously consider restarting QE asset purchases relatively soon,” added Robert Sierra, Director in Fitch’s Economics team..

We also foresee the ECB announcing a one- to two-year long-term refinancing operation (LTRO) in March to replace the existing TLTRO2 programme, which matures from June 2020. The rationale for a new targeted LTRO (TLTRO) is less convincing in light of improved conditions in the banking sector, but the ECB will want to avoid an unwarranted tightening in credit conditions by abruptly withdrawing liquidity facilities.

Last Wednesday, the European Banking Authority (EBA) began the process of stress testing Europe’s largest banks in an effort to assess their individual capital adequacy under stressed conditions. The publication of a draft stress test methodology coincided with the announcement of the resolution of Spain’s Banco Popular Espanol, a bank that fared relatively well in the 2016 stress test results published 10 months ago.

The draft stress test methodology and the timing of its publication convey two key messages for European Union (EU) banks andinvestors. First, the stress test for 2017-18 will be tougher, given that it will include the new accounting rule known as International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) No. 9, which requires that banks set aside provisions on all loans in advance of default. Second, notwithstanding EU supervisors’ efforts to harmonise rules and enhance stress testing, Banco Popular’s failure has revealed once more the principal limitations of stress testing in signalling potential failures, which has resulted in scepticism toward the exercise.

The 2018 stress test will once again look at the effect of macroeconomic stress on a bank’s viability, taking into account market risk and litigation risk. Additionally, the test will include simulations of risk charges under IFRS 9 of expected credit losses. IFRS 9 addresses the issue of loan-loss provisions being “too little and too late,” something regulators identified as a shortcoming that amplified the 2007-09 banking crisis. The accounting change will require banks to model credit risk losses for loans even before they have defaulted, and increase the level of provisions as they start to deteriorate.

Considering that banks must use IFRS 9 starting in January 2018, the inclusion of the new rule in the next stress test is not surprising. However, its potential effect on banks’ capital in the stress test is opaque given the difficulty in estimating stressed simulated risk provisions that must be based on a new accounting concept ahead of its implementation deadline. However, incremental risk provisioning under IFRS 9 will focus on loans that show deterioration in borrowers’ credit quality since inception of the loan. Therefore, we expect banks that are challenged by low growth and persistent asset quality pressures will be more affected. Although the stress test again will not involve a pass-or-fail decision benchmarked against a hurdle rate, the 2018 stress test is still likely to force some banks to hold more capital.

With the resolution of Banco Popular, whose subordinated creditors were bailed-in and their investment effectively wiped out, we expect that the EBA’s 2018 stress test again will single out weak candidates, but the results still may not reliably predict the next failure. Although the 2016 stress test formally identified Banco Popular as the weakest among the six participating Spanish banks, it was by no means among the most vulnerable candidate when taking into account a capital measure undertaken shortly after the year-end 2015 cut-off date for the test. The bank reported a relatively weak common equity Tier 1 ratio of 7.0% in the adverse scenario, but, adjusted for a €2.5 billion rights issue that had been concluded by the time the results were published, the bank’s result ranked second-best in the Spanish peer group, with a solid 10% pro forma result.

In the wake of the Italian constitutional referendum, the country’s banking crisis is going from bad to worse. The European Central Bank (ECB)‘s decision to refuse an extension to Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena to raise €5 billion (£4.2 billion) has left the country’s third-largest bank facing a government bailout that looks likely to inflict severe pain on many ordinary Italian savers.

As if that were not enough, Italy’s biggest bank, UniCredit, announced a restructuring plan that requires a capital raising of €13 billion in the first three months of next year. Given the torrid time Monte dei Paschi has had trying to find sufficient private backing, will UniCredit need help from the Italian taxpayer, too?

The problems at Monte dei Pashci and UniCredit reflect the parlous state of the country’s banking system. The economy has been struggling for a number of years and borrowers have been defaulting, creating a mountain of bad loans. Around 20% of bank loans are bad, amounting to a staggering €360 billion (about one-third of all bad loans in the eurozone).

More than 70% of these loans are to small and medium-sized businesses. Small firms in Italy tend to have numerous bank relationships, commonly with accounts at four or five banks. Hence their defaults have polluted bank balance sheets across the sector.

I hear critics saying the Bank of Italy, the regulator, was slow to deal with the problem, only intervening within the past 18 months. Individual banks also stand accused of being complicit in rolling over non-performing loans – disguising the true picture. The situation is worse for banks in the south, where economies have been faring even worse. And Matteo Renzi’s defeat in the referendum exacerbates the whole problem by denying the sector reforms to help banks recover bad loans by speeding up insolvency processes, among other things.

Too much good life? Irene van der Meijs

The bail-in problem

The Bank of Italy restructured four small banks last year, but its ability to rapidly resolve problems at bigger banks is hindered by EU bank bailout and state aid rules. These say direct state aid cannot be provided until a bank has looked for private injections of capital, including making investors in a class of bank debts known as bail-in bonds take some pain by converting their bonds into shares.

The logic is that these unsecured bondholders should bear the same risks as shareholders, thus reducing the burden on the taxpayer in the event of a rescue. Investors have nonetheless been lured into these bail-in bonds, including those of Monte dei Paschi and UniCredit, by higher returns than other bank bonds, betting they would not end up being converted.

In most countries institutional investors including pension funds and insurance companies are the main investors in unsecured bank bonds. But in Italy there’s an additional problem: households own about a third of the total – 40,000 retail investors own Monte dei Paschi bonds, for instance.

When the four small Italian banks were restructured, the value of their bonds was wiped out. In addition to political condemnation, there were widespread protests and at least one suicide. Particularly when the country is going through such a politically volatile period, the government will be very wary of another bail-in as part of any Monte dei Paschi rescue. Depositors above around €90,000 are also supposed to lose out, though it is hard to see this being politically possible regardless of the rules.

What comes next

The ECB decided the request from Monte dei Paschi for a deadline extension for its recapitalisation from year-end to January 20 was a delaying tactic. It said the bank had to sort things out faster – together with the new Italian government, headed by Renzi loyalist Paolo Gentiloni. This means the world’s oldest bank, established in 1472, now has barely two weeks to find a private solution and avoid inflicting a bail-in on the country.

The recapitalisation plan has three components. The first is a voluntary bond swap – similar to bail-in bonds, except bondholders choose whether to convert their bonds to shares or not. This has raised around €1 billion from institutional investors, but there has been no take-up from retail investors. They have viewed the exchange as too risky and have been concerned about whether the regulator has fully approved the retail swap transactions.

Second, Monte dei Paschi hopes to get €1 billion from Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund. Finally, a consortium of banks has said it will try to sell the bank’s shares in the open market. They will not be underwritten, however, so there is no guarantee of raising significant funds.

The sick old man of Italy. francesco carniani

So even if the capital-raising is successful there is likely to be a shortfall of several billion euros. The question then is what happens next. The government will certainly not let this historic institution fail, despite a national debt in excess of 130% of GDP – among the highest in the world.

Failure to resolve the problems would compound financial market jitters surrounding Italian banks. That could lead to widespread failure and the export of similar problems, due to a collapse of confidence, to other fragile eurozone countries.

To unlock an injection of state funds the Bank of Italy would therefore need to decide whether to follow the EU rules and risk the wrath of the retail bondholders with a bail-in – and/or provide guarantees to cover their losses. Ironically, the ECB would then potentially have to provide guarantees, liquidity injections and capital support to maintain confidence in the Italian system.

Meanwhile, all eyes will be on the UniCredit capital-raising to see if it fares any better. It should do: UniCredit’s proposed rights issue requires market credibility that Monte dei Paschi does not have at present. Were it to hit difficulties, however, this crisis will move from major to monumental. Either way, it looks likely to be some time before the problems in Italian banking even begin to look like being resolved.

Author: , Professor of Banking and Finance, Bangor University

Poul Thomsen, Director, European Department, IMF gave a press conference on the Euro area. Growth estimates are up slightly in the short term, but there are significant structural issues across fiscal management and banking supervision and longer term growth remains mediocre.

I am going to explain to you that for Europe actually we are revising growth forecast up even for the Euro area although slightly. And the main challenge is really of a medium-term nature.

Let me start with the Euro area. The recovery is continuing after a strong start at the beginning of the year. We are now projecting growth to be 1.7 percent in 2016. That’s a slightly upward revision compared to when we were together six months ago. However, the medium-term forecast is indeed quite mediocre. We have potential growth around 1.5 percent. With that we have several important countries that even 10 years down the road will still have unemployment above pre-crisis levels, which is clearly unsatisfactory.

The reasons for the subdued outlook I think are well-understood by now, there are some long-term challenges, demographic challenges, low productivity, like in other advanced countries and there are, secondly, a number of crisis legacies. There is high structural unemployment. There is high debt, and non‑performing loans in the banking sectors.

So the picture is nuanced. The recovery is on track. The short-term outlook is indeed slightly better than when we were together six months ago, but clearly the political uncertainty in the sense of fragility has increased, Brexit, the refugee crisis, et cetera. So there clearly are downside risks that are dominating if we look beyond the near term.

What are the policy implications? For one, monetary policy, we continue to think that the ECB is doing the right thing with the accommodative monetary policy. We see that there is space to do more if needed, but clearly the scope for doing more on monetary policy is limited. Clearly, monetary policy is being overburdened.

Two, fiscal policy. The overall fiscal stance in the Euro area this year is slightly expansionary. Next year it’s set to be neutral. We think this is appropriate given where we are in the cycle. As I said, the recovery is broadly proceeding as expected.

But we do think that the distribution could be better, we think that some countries with fiscal space should use that space. And we think a number of countries with high debt should consolidate more than currently is the case.

We still have seven countries inside the Euro zone that are set to have debt above 100 percent of GDP which, of course, significantly limits fiscal space. I think it’s important to preserve broad, political support inside the Euro zone not least for the policy of the ECB. I think it’s critical that the fiscal rules are implemented as envisioned and that fiscal adjustment is not delayed during times like now when the recovery is on track.

Countries without fiscal space, as we have said before, can also improve the growth outlook by improving the composition of their budget to promote a stronger potential growth. We continue to support the so-called Juncker Initiative and the plans in this regard for an extension and enlargement are welcome.

Third, structural reforms. Unemployment in the Euro area is primarily structural and the key issue is structural reforms to boost potential growth. There are good examples of how structural reforms really have a good payoff in the Euro zone, but there are clearly also signs of adjustment fatigue and a lost reform momentum in recent years.

In that regard, we are supporting talking about policy efforts to develop outcome-based benchmarks to incentivize structural reform and I think this is some work we want to encourage. As far as the priorities, I shall not comment on the structural reforms. They are very country-specific as you know. To reduce the labor tax wedge and the labor market duality; to open up closed professions; to proceed with a single market, covering a single market in services, capital, energy and transport. But as I said, this really varies from country to country.

Fourth, we need the repair of the banking sector’s balance sheets to continue. We have the problem of non-performing loans, as you know, in a number of countries. We welcome the work that is going on inside the ECB in this regard with the high level working groups. We think it’s critical that the supervisor sets ambitious targets for reduction in NPLs over time, over time. It should not be something excessively pro-cyclical. This has to be over time, but there needs to be ambitious targets and there needs to be follow up with close monitoring and review.

There are some other issues that my colleagues in MCM have discussed with you. I shall not go into them. Clearly, the European banks have an issue with profitability and need to improve their business model but this has been discussed at length by my colleagues so I’ll just mention it. It’s a very important issue.

So let me sum up for the Euro area. Where are we? Cyclical recovery on track. Monetary policy appropriate. Fiscal policy overall appropriate with some need to redistribute, so countries who have space should use it, while all the countries with high debt should consolidate more.

There’s a lot of talk about Germany. We think that Germany has some fiscal space and should use it. We have about 0.5 percent of GDP in our recently published staff report and we see a case for using it particularly on infrastructure. And this will help, will have a positive spillover, but it is a limited spillover.

The problem with the low growth in the Euro zone is mainly a structural one, that requires structural reforms in the individual countries and we should not believe that just to get Germany to do more is going to solve the Euro zone’s growth problem. It is mainly a structural problem that requires structural reforms.

One more issue before I turn to Eastern Europe outside the Euro zone. The UK, Brexit, this is a new and unexpected development since we last met. While sterling obviously has declined sharply, there have been no major negative market reactions in part because of a very strong and appropriate policy reaction by central banks, by the Bank of England, but also announcements by the ministry of finance to stand ready with an appropriate fiscal policy response if needed.

As to GDP, we had two scenarios before the Brexit vote, a modest impact and a strong impact. We are largely in the modest impact scenario. Actually, we have revised slightly upwards our UK growth forecast because essentially of developments in Q2 data that came out a lot stronger than we had before. But we are largely in the modest impact scenario and that’s of course very good news. The main issues are, as you know, in the longer term how is this going to be handled? And it’s absolutely critical that the uncertainty in this regard is settled sooner rather than later.

Let me turn to Eastern Europe. Despite the sort of mediocre growth globally, the recovery in Eastern Europe is nearly complete. Output gaps are closing and unemployment is falling to pre-crisis levels. And that is obviously good news. It’s on the back of strong wage growth and accelerating credit growth and this is much welcome. The key challenge facing Eastern Europe is also of a medium-term nature. It is to boost potential growth.

We estimate that potential growth is about half of what it was before the crisis. To some extent, it is not surprising, in the sense that the first 25 years [of transition] clearly provided some easy catch-up gains in productivity, some low-hanging fruits, and it was always in the cards that the next 25 years, if you want, would be a bit more difficult. It’s a more difficult reform, more fundamental and institutional reforms, and this is the scaly part of the challenge.

There are also some crisis legacies, that weigh on growth but so it’s a mix of issues. The key challenge in Eastern Europe is to overcome these things that are weighing on potential growth and get potential growth back up. Without that increase in potential growth, Eastern Europe will not be able to continue the current growth rates without experiencing external imbalances.

So that’s the challenge. In terms of the macroeconomic policy mix, with inflation still low but a number of countries with a high [external] debt, we think that generally the current monetary policy stance in Eastern Europe is appropriate, but we would like to see more fiscal adjustment in a number of these countries than actually is taking place.

Now when we talk about Eastern Europe, I find it more and more difficult because in some ways the group is getting more and more heterogeneous. There are some countries that are doing very well and the other countries that are doing not so well. So the challenges they face are difficult to sort of generalize in a broad presentation like this.

Broader structural reforms, of course, are critical: measures to increase investment. And I think here the key challenge is what I alluded to before, fundamental institutional reforms that are needed to allow Eastern Europe to sort of continue to converge apace with Western Europe.

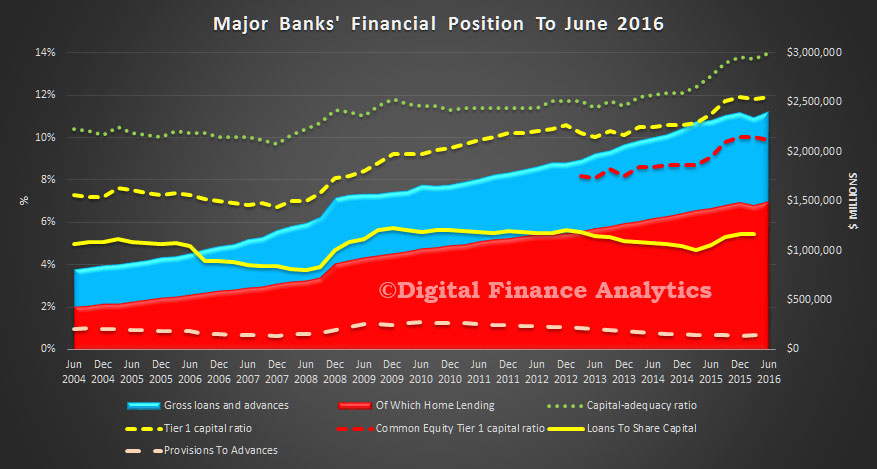

The logic since the GFC is that capital ratios need to be higher, so if a bank gets into difficulty, there is a greater chance it can be managed to an outcome without needing government bail-outs or depositors loosing their shirts. This is one way of managing the “Too Big To Fail” problem. For example, in Australia, the big four have lifted their overall ratios from 10% to 14%. Tier 1 capital has also risen. But of course higher capital costs.

However, now it seems that European Banks (who have been struggling to lift capital ratios to a reasonable level – The 2016 stress testing is worth reading) may be let off the hook.

A speech by VP Dombrovskis at the European Banking Federation Conference: Embracing Disruption has suggested that revised regulations due soon are likely to water down capital requirements in Europe. Significantly, the speaker is in charge of Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union in the EU.

Equalising average risk weights across the world cannot be the answer, we need an intelligent solution which takes account of the individual banks’ situations and maintains a risk sensitive approach to setting capital requirements. Different banks have different business models which involve different levels of risk. This needs to continue to be recognised so as to preserve Europe’s diverse financial landscape.

The Commission remains committed to striking the right balance between supporting reforms at a global level and respecting the diversity of Europe’s financial sector. We will continue to strive for a financial framework that gives companies enough space to innovate and consumers the certainty they need. And we will follow through on our work to review our legislative framework and make targeted adjustments to support investment and sustainable growth in Europe.

A solution we could not support is one which would weigh unduly on the financing of the broader economy in Europe. At a time when we are focused on supporting investment, we want to avoid changes which would lead to a significant increase in the overall capital requirements shouldered by Europe’s banking sector. This is a clear Commission position. It received strong backing from all EU countries in July. It is in line with the Basel Committee’s commitment.

With this work in mind, we will come forward with a revision of our own legislation the Capital Requirement Regulation and its sister directive CRD this autumn. Our aim has not changed. We want legislation which supports financial stability, but allows banks to lend and support investment in the wider economy.

Deutsche Bank, the 11th largest bank in the world, plunged to fresh all time lows on speculation whether the German government would or wouldn’t provide state aid to the bank (if needed), forcing the bank to state it does not need the funds at the same time as the government urged markets that “you can’t compare” Deutsche Bank and that “other” bank, Lehman Brothers, although looking at the chart, one may beg to differ.

However, while DB stock closed at session lows, over 7% lower on the day, with its market cap of $16 billion now rapidly approaching the $14 billion litigation settlement demanded by the DOJ, the bad news did not stop there.

In a report issued by Citigroup titled “Capital, Litigation & AT1 Coupon Risks”, bank analyst Andrew Coombs says that Deutsche reported an end-June CET1 ratio of 11.2% pro-forma for the HXB stake sale, but still only targets c11% by end-2016 as further litigation charges are assumed, with management expecting to resolve four of the five major outstanding litigation cases this year. To this Citi says that it “struggles” to see how Deutsche Bank can reach the fully-loaded SREP requirement of 12.25% in the medium-term.

Meantime, one of the largest derivatives books in the world is imploding. Deutsche Bank has over $61 TRILLION in derivatives on its books. It has lost nearly a quarter of its value in the last three weeks.

DB is not alone here. Across the board, we’re getting signs of an impending banking crisis in Europe. Credit Suisse (CS) is trading BELOW its 2012 banking crisis lows.

So is Barclays (BCS)

The EU banking system is $46 TRILLION in size. This is THREE TIMES larger than the US banking system, which nearly imploded the markets in 2008.

And the EU banking system as a whole is leveraged at 26 to 1. Lehman Brothers was leveraged only slightly higher than this at 30 to 1.

Indeed, we believe the global markets are on the verge of another Crisis, triggered by a crisis of faith in Central Banks.

2008 was Round 1 triggered by Wall Street banks. This next round, Round 2, will be even worse as faith in Central Banks collapses

If Deutsche Bank went down, and the German Government didn’t step in with a rescue, that would be a huge blow to Europe’s largest economy – and the global financial system. No one really knows where the losses would end up, or what the knock-on impact would be. It would almost certainly land a fatal blow to the Italian banking system, and the French and Spanish banks would be next. Even worse, the euro-zone economy, with France and Italy already back at zero growth, and still struggling with the impact of Brexit, is hardly in any shape to withstand a shock of that magnitude.

What we do know is that if some €42 trillion in derivatives – some three times more than the GDP of the European Union – were to suddenly lose their counterparty, the systemic damage would be unprecedented.