The dots that the FOMC members contribute to the plot indicate their expectations for the federal funds rate.

Technically, it’s what they think rates should be, not a prediction of what rates will be on those dates. Is that a forecast? You can call it whatever you like. I think “forecast” is close enough.

But before we analyze the whatever-you-call-it, let’s look back at the not-so-distant past.

Here’s a rate history of the last 16 years:

I’ve highlighted this fact before, but it’s worth mentioning again: In 2007, less than a decade ago, the fed funds rate was over 5%. So were the interest rates for Treasury bills, CDs, and money market funds.

People were making 5% on their money, risk-free. It seems like ancient history now, but that year marked the end of a halcyon era of ample rates that most of us lived through.

The chart below shows historical certificate of deposit rates—but remember, you could put your money in a money market fund and do better than the six-month certificate of deposit yield, back in 2007.

Today’s young Wall Street hotshots have never seen anything like that. To them, the jump from 0.5% to 0.75% must seem like a big deal. It’s really not. If the chart above were a heart monitor readout, we would say this patient is now dead and that last blip was an equipment glitch.

The point to all this is that these near-zero rates to which we have all adapted are by no means normal or necessary to sustain a vibrant economy.

We’ve done fine with much higher rates before. They are even beneficial in some ways—they give savers a return on their cash, for instance. But there are likely to be consequences once we embark on this rate-increase cycle.

The FOMC cast members are all old enough to remember those bygone days of higher rates as well as I do. So, we would think they might at least foresee a return to normalcy at some point in the future.

Not so.

The FOMC members see nothing of the sort

Here is the official dot plot published by the FOMC. (I have included their preferred heading so that no one complains about my calling it a forecast, even though that’s what it is.)

Each dot represents the assessment of an FOMC member. That group includes all the Fed governors and the district bank presidents. All 17 of them submit dots, including the presidents of districts who aren’t in the voting rotation right now. There would be 19 dots if the two vacant governor seats had been filled.

That flat set of dots under 2016 represents a rare instance of Federal Reserve unanimity: They all agree where rates are right now. (See, consensus really is possible.) The disagreement sets in next year. For 2017, there’s one lone dot above the 2.0% line, but the majority (12 of 17) are below 1.5%.

Nevertheless, it will be a much different year than this one if they follow through. The dots imply that the fed funds rate will rise a total of 75 basis points next year.

Presumably, that would be three 25 bps moves, but they can split it however they want. They could ignore their expectations completely, too. This time last year, the FOMC said to expect a 100 bps rise, or four rate hikes, in 2016. We got only one.

Follow the dots on out and you see that their assessments trend a little higher in the following two years, and then we have the “longer run” beyond 2019. Most FOMC participants think rates at 3% or less will be appropriate as we enter the 2020s.

The most hawkish dot is at 3.75%.

Think about what this means

Today’s FOMC can imagine raising rates only to the point they fell to about halfway through their 2007–2008 easing cycle. They see no chance that overnight rates will reach 5% again. None.

Here is another view of the same data, that shows how the dots shifted.

Looking at each set of red (September) and blue (December) dots, we see only a slightly more hawkish tilt than we saw three months ago. The “Longer Term” sets are almost identical—two of the doves moved up from the 2.5% level, while the two most hawkish hung tight at 3.75% and 3.50%.

That word hawkish is relative here. By 2007 standards, these two voters are doves. But, Toto, I’ve a feeling we aren’t in 2007 anymore.

Tag: Federal Reserve

Federal Reserve offers vote of confidence in US economy (so there’s no reason to panic)

No one was really surprised that the Fed raised its target interest rate by one-quarter of a percentage point. Yet some people are really upset about it and worried this will slow down a fragile economic recovery.

I would disagree with that view for several reasons.

My biggest reason is that a quarter-point is not a very big change. I recognize that the economy isn’t yet chugging along at full steam yet, but the Fed acknowledged that by making the smallest increase it could and implying that it’s unlikely to be followed by another increase in January or even in March or May. If we did get another increase that soon, it would only be in response to clear signs of strong economic growth in the U.S.

No magic wand

We should remember that monetary policy is not a magic wand.

Changes like this take time to percolate through the economy and are made with the expectation that their full impact won’t be experienced for several months. What the Fed really said today was that it fully expects that the economy will continue to strengthen over the coming three to six months.

One argument made by those against today’s rate hike (and any others the Fed might be considering) is that there’s still considerable slack in the U.S. labor market. Put another way, our recovery from the Great Recession hasn’t yet reached everyone – meaning a lot of people are still out of work or can’t get the jobs they want – and we should keep rates as low as possible to continue to encourage businesses to expand and to hire more workers.

There’s some merit to this concern. The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ broadest measure of labor underutilization is still at 9.3 percent (including discouraged workers and people who can’t find full-time work). While that certainly sounds bad, this rate was over 17 percent during the worst parts of the recent recession, so we’ve made tremendous progress.

The economy continues to create jobs at a healthy pace – adding 178,000 jobs last month and adding an average of 188,000 per month over the past year. In other words, the Fed is giving our economy a vote of confidence that this level of job creation is likely to continue.

Why a stronger dollar isn’t a concern

Another big concern is that this increase will lead to the dollar getting even stronger in international currency markets.

There are several reasons for the dollar’s rise – most of them have nothing to do with monetary policy. This means that the dollar would continue to strengthen even if the Fed did nothing. One way to look at the dollar’s recent rise is the world is saying they are confident that the U.S. economy will continue to outperform most other regions.

A rate increase is probably a good thing right now because we’ve had the lowest interest rates ever for nearly a decade, and loose monetary policy has probably done about as much as it can for now. It’s not that I think higher rates will be even more helpful, but that I think low rates aren’t likely to help the economy much anymore.

I’d like to see rates return to a slightly higher level so that we have the flexibility to decrease them if needed. In the past, we’ve relied almost exclusively on monetary policy to moderate the ups and downs in the economy and that flexibility isn’t available to us right now.

Some risks

The Fed has certainly heard President-elect Donald Trump talk about his ideas for significant tax cuts and infrastructure investments. Congress has expressed mixed feelings about these proposals, so it’s not certain that they will actually happen. If they do, each of these would boost the economy some, although not right away.

Another reason to raise rates earlier rather than later stems from the beliefs of some economists that loose monetary policy has been a causal factor in several past recessions.

I’m not a strong proponent of this view, but I agree that this potential exists. I’m a more worried about the potential for inflation when banks decide to start using the US$2 trillion they have saved up and deposited at the Fed, but that’s a conversation for another time.

Looking ahead to 2017, a lot will depend on how well the new administration does and how successful they are at getting their proposals through Congress. Assuming the economy continues to plod along, I’d expect another quarter-point increase in mid- to late 2017.

Author: , Associate Professor of Economics, Vassar College

Yellen’s Fed faces a tricky rates dilemma in 2017 that may end up tripping up Trump

Editor’s note: The Federal Reserve’s policy-setting committee raised its target interest rate a quarter-point to a range of 0.5 percent to 0.75 percent, only the second such move in eight years. In the widely anticipated decision, the Fed signaled it anticipates raising rates another 0.75 percentage point in 2017 – likely in three quarter-point hikes – a faster pace of tightening than previously expected. We asked two experts to analyze what this will mean for the not too distant future.

Between a rate hike and a hard place

Steven Pressman, Colorado State University

As almost everyone expected, the Fed raised interest rates, and banks will now pass their higher costs on to companies and consumers, leading to higher borrowing rates throughout the economy.

The bigger issue, however, concerns likely increases in 2017. Here the message was somewhat ambiguous. While indicating that three 0.25 percentage point increases were possible in 2017, compared with the previous guidance that only two rate hikes were likely next year, Janet Yellen stressed in her press conference that any changes would be small and remain highly uncertain. She continually noted that the Federal Reserve would have to adjust its thinking in 2017 based on actual economic circumstances.

The Federal Open Market Committee press release was likewise rather ambiguous. It indicated that monetary policy “remains accommodative” and that future adjustments will depend on the “economic outlook” and “incoming data.”

The important takeaway from all this is that it is really not clear what the Fed will do next year. The reason for this is that the Fed is damned if they raise interest rates considerably in 2017 and damned if they don’t.

On the one hand, debt remains a Damocles sword hanging over the U.S. economy, and a rise in rates could cut the thread. Household debt is approaching levels reached before the 2008 financial crisis, which suggests that households may be approaching the point at which they cannot repay their loans – something that can bring down banks and the U.S. economy. And real median household income remains US$1,000 below pre-Great Recession levels and $1,500 below its all-time peak in the 1990s. U.S. households, responsible for 70 percent of all spending in our economy, face a double squeeze that cannot continue.

Worse still, many households remain underwater on their mortgages. Others are slightly above water, unable to come up with the realtor commissions and moving expenses that would let them sell their home and find a more affordable place to live. Higher interest rates will worsen this problem by reducing home affordability and prices.

On the other hand, at some point, perhaps soon, the U.S. economy will enter another recession. If the tax cuts and spending increases proposed by President-elect Trump get enacted, a ballooning budget deficit (made worse by the onset of a recession) will hinder the ability of fiscal policy to create jobs. Interest rate cuts then become our only viable policy tool.

So with rates already near zero, central banks cannot lower them very much. For this reason, they want to load up on ammunition, and push them up some. At the same, time they fear the consequences of doing this. Today’s Fed guidance was ambiguous for a good reason – they are caught on the horns of a nasty dilemma.

How higher rates will hurt Mexico and tie up Trump

Wesley Widmaier, Griffith University

Donald Trump has promised to build a wall and make Mexico pay. But the Fed’s decision to continue raising rates higher – known as tighter monetary policy – may push Trump to send money abroad, even to Mexico, a common target of his scorn on the campaign trail.

History shows that monetary policy decisions can have complex effects.

With a U.S. recovery continuing, the Fed’s tightening is raising fears of a reaction similar to the 1994 Mexican peso crisis. If this happens, the Trump administration may face hard choices.

Just like today, early 1994 saw then-Fed Chair Alan Greenspan move from an easy money stance and resume raising rates. Greenspan argued that the stock market was flirting with a bubble, bank earnings were low and inflation might revive. Raising interest rates was seen as the solution to ease the market bubble, pull money back from emerging markets and tamp down on a return of inflation.

However, the Fed’s moves back then had unexpected effects. Like many middle-income countries today, Mexico had issued dollar-denominated tesobonos to insure against exchange rate risk. But as the Fed raised rates over 1994, Mexico found it harder to make payments on the bonds, prompting a run on the peso.

The U.S. responded with a $50 billion rescue. Dollars had to flow south – or a Mexican collapse might send immigrants north.

Of course, this is not a dynamic unique to Mexico. As Fed moves raise the cost of servicing dollar-denominated debts, increased debt-servicing costs could have global repercussions.

However, Mexico’s economy has been a subject of some recent concern. If Fed restraint heightens those concerns, Trump may need to forget the wall – and pay Mexico instead.

Fed Lifts Rate As Expected

The Fed has lifted its target rate by 0.25%, the second move up in 10 years. They signalled only gradual increases in the federal funds rate which is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run.

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in November indicates that the labor market has continued to strengthen and that economic activity has been expanding at a moderate pace since mid-year. Job gains have been solid in recent months and the unemployment rate has declined. Household spending has been rising moderately but business fixed investment has remained soft. Inflation has increased since earlier this year but is still below the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run objective, partly reflecting earlier declines in energy prices and in prices of non-energy imports. Market-based measures of inflation compensation have moved up considerably but still are low; most survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations are little changed, on balance, in recent months.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. The Committee expects that, with gradual adjustments in the stance of monetary policy, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace and labor market conditions will strengthen somewhat further. Inflation is expected to rise to 2 percent over the medium term as the transitory effects of past declines in energy and import prices dissipate and the labor market strengthens further. Near-term risks to the economic outlook appear roughly balanced. The Committee continues to closely monitor inflation indicators and global economic and financial developments.

In view of realized and expected labor market conditions and inflation, the Committee decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate to 1/2 to 3/4 percent. The stance of monetary policy remains accommodative, thereby supporting some further strengthening in labor market conditions and a return to 2 percent inflation.

In determining the timing and size of future adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will assess realized and expected economic conditions relative to its objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments. In light of the current shortfall of inflation from 2 percent, the Committee will carefully monitor actual and expected progress toward its inflation goal. The Committee expects that economic conditions will evolve in a manner that will warrant only gradual increases in the federal funds rate; the federal funds rate is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run. However, the actual path of the federal funds rate will depend on the economic outlook as informed by incoming data.

The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction, and it anticipates doing so until normalization of the level of the federal funds rate is well under way. This policy, by keeping the Committee’s holdings of longer-term securities at sizable levels, should help maintain accommodative financial conditions.

US Regulators Say Wells Fargo Has More To Do

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Federal Reserve Board on Tuesday announced that Bank of America, Bank of New York Mellon, JP Morgan Chase, and State Street adequately remediated deficiencies in their 2015 resolution plans. The agencies also announced that Wells Fargo did not adequately remedy all of its deficiencies and will be subject to restrictions on certain activities until the deficiencies are remedied.

Resolution plans, required by the Dodd-Frank Act and commonly known as living wills, must describe the company’s strategy for rapid and orderly resolution under bankruptcy in the event of material financial distress or failure of the company.

In April 2016, the agencies jointly determined that each of the 2015 resolution plans of the five institutions was not credible or would not facilitate an orderly resolution under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, the statutory standard established in the Dodd-Frank Act. The agencies issued joint notices of deficiencies to the five firms detailing the deficiencies in their plans and the actions the firms must take to address them. Each firm was required to remedy its deficiencies by October 1, 2016, or risk being subject to more stringent prudential requirements or to restrictions on activities, growth, or operations. The review and the findings announced today relate only to the joint deficiencies identified in April 2016.

The agencies jointly determined that Wells Fargo did not adequately remedy two of the firm’s three deficiencies, specifically in the categories of “legal entity rationalization” and “shared services.” The agencies also jointly determined that the firm did adequately remedy its deficiency in the “governance” category. In light of the nature of the deficiencies and the resolvability risks posed by Wells Fargo’s failure to remedy them, the agencies have jointly determined to impose restrictions on the growth of international and non-bank activities of Wells Fargo and its subsidiaries. In particular, Wells Fargo is prohibited from establishing international bank entities or acquiring any non-bank subsidiary.

The firm is expected to file a revised submission addressing the remaining deficiencies by March 31, 2017. If after reviewing the March submission the agencies jointly determine that the deficiencies have not been adequately remedied, the agencies will limit the size of the firm’s non-bank and broker-dealer assets to levels in place on September 30, 2016. If Wells Fargo has not adequately remedied the deficiencies within two years, the statute provides that the agencies, in consultation with the Financial Stability Oversight Council, may jointly require the firm to divest certain assets or operations to facilitate an orderly resolution of the firm in bankruptcy.

The Federal Reserve Board is releasing the feedback letters issued to each of the five firms. The letters describe the steps the firms have taken to address the deficiencies outlined in the April 2016 letters. The feedback letter issued to Wells Fargo discusses the steps the firm has taken to address its deficiencies and those needed to adequately remedy the two remaining deficiencies.

The determinations made by the agencies today pertain solely to the 2015 plans and not to the 2017 or any other future resolution plans. In addition to requiring that the firms address their deficiencies, in April the agencies also identified institution-specific shortcomings, which are weaknesses identified by both agencies, but are not considered deficiencies.

The agencies in April also provided guidance to be incorporated into the next full plan submission due by July 1, 2017, to the five firms, as well as Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Citigroup, and will review those plans under the statutory standard. If the agencies jointly decide that the shortcomings or the guidance are not satisfactorily addressed in a firm’s 2017 plan, the agencies may determine jointly that the plan is not credible or would not facilitate an orderly resolution under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code.

The decisions announced today received unanimous support from the FDIC and Federal Reserve boards.

Feedback letters:

Bank of America (PDF)

Bank of New York Mellon (PDF)

JP Morgan Chase (PDF)

State Street (PDF)

Wells Fargo (PDF)

How the Fed joined the fight against climate change

The Federal Reserve’s policy committee is expected to lift its target interest rate a quarter-point – to a range of 0.5 percent to 0.75 percent – at its final meeting of 2016.

The main reasons the Fed has kept rates near zero for eight years have been to restore economic growth and lower unemployment – goals that have been largely achieved. But doing so has had an important, if little noticed – and probably unintended – side effect: It has been promoting efforts to curb global warming.

Solar projects like this one in Pueblo, Colorado, become more attractive when rates are very low. Rick Wilking/Reuters

That is, the ultra-low interest rates have favored sustainable projects like wind farms and corporate solar installations, the kind that are necessary if the world is to transition to a low-carbon future in line with the Paris climate accord. At the same time, they have discouraged unsustainable, high-carbon projects like coal power plants that appear cheap but become unprofitable over time when you factor in the cost of carbon.

Government policy, without help from the Fed, could nudge businesses and consumers to reduce carbon emissions. But, as my research shows, governments walk a fine line when setting carbon policies. They may fail to adequately address climate risks with policies that are too lenient or come too late or they may create systemic instability and financial crises with policies that are too harsh or aggressive.

So one way to reduce these risks is for the business sector to voluntarily and swiftly proceed with the transition to a low-carbon, “green” economy. And thanks to the Fed, the low-interest rate environment is supporting just that.

Opportunity costs

Under the Paris Agreement, more than 190 countries agreed to limit the global temperature increase to below 2 degrees Celsius.

Just last month, the agreement entered into force after countries representing 55 percent of global emissions ratified it.

But the accord doesn’t actually force countries to do anything to live up to their pledges, and many companies have long been resistant to the kinds of policies, like carbon taxes and cap-and-trade systems, that would achieve those aims. Furthermore, U.S. President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to exit the accord.

So how can we reach those goals?

My own research suggests one way to get there is through the widespread adoption of capital budgeting techniques – the process of determining the viability of long-term investments – that take into account the opportunity costs of both financial capital and carbon dioxide.

The opportunity cost of financial capital is simply the rate of return the company could have earned on its next best investment alternative. If a project cannot return at least that, it should not be funded.

On the other hand, atmospheric capital, as measured by carbon dioxide emissions, is not privately owned, making its opportunity cost much harder to measure. This cost includes the benefits we forgo when emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, such as more stable agricultural yields, reduced losses from less violent weather, greater biodiversity, etc. If a project cannot generate a return on carbon that is at least commensurate with the benefits we give up as a result of the project’s carbon emissions, the project should be rejected.

Estimates of the social cost of carbon for the next 35 years have been produced by the U.S. Interagency Working Group on Social Cost of Carbon and other organizations, such as Stanford University. Estimates from these two sources range from approximately US$37 to about $220 per ton of carbon dioxide, while many companies report internal carbon prices at or below the lower end of this range.

Historically, companies creating these costs haven’t borne the brunt of it, but that is changing as countries, states, provinces and cities are imposing or planning to impose various carbon pricing mechanisms. Examples include China, the European Union, California, Canada and U.S. states in the Northeast and Middle Atlantic region.

Since the planning horizon for long-term capital budgeting projects like power plants and solar installations often extends out 10 to 20 years or more, that carbon cost is likely to grow quite a bit, and more of it will be billed to the companies doing the polluting, meaning carbon-intensive projects will become increasingly expensive.

While the Fed does not influence the opportunity cost of carbon – and whether companies account for it – it does influence the opportunity cost of financial capital. Specifically, the Fed influences the time value of money by setting interest rates.

Patient investors

The time value of money is the compensation borrowers pay investors for their patience.

If the interest rate is high, people are very impatient and prefer cash flows now, perhaps leading them to prefer to invest in a polluting power plant that pays out right away rather than an expensive windmill farm. If the interest rate is very low, on the other hand, people have easy access to funding and can wait a long time for cash flows that come much later. That makes longer-term, riskier projects like that windmill farm more attractive because their value will grow as governments punish carbon emitters – and investors will be rewarded for their patience.

It is the Fed’s manipulation of the time value of money that affects the choice of high-carbon versus low-carbon projects, especially when an expected rising opportunity cost of carbon is included in the analysis. So with rates hovering at unprecedented lows for nearly a decade, today’s investors can afford to be patient.

Investments in the green economy that initially may seem expensive but pay off over the long term are favorably viewed when rates are low because positive cash flows in the more distant future are barely discounted. That is, their present value equivalents (the current worth of a future sum of money) are almost the same as the future amounts because so little interest would be earned were they invested elsewhere. That means the positive future cash flows are more likely to outweigh the initial costs of green projects.

In fact, there has been a solid 57 percent increase in renewable energy capacity in the U.S. since 2008, while dirtier power sources – though still dominant – have waned.

Coal, for example, made up 21.5 percent of energy production in 2015, down from 34 percent in 2008. Renewables, meanwhile, climbed to 11.5 percent from 10.2 percent in the same period. Actual consumption tells a similar story, with coal-making up 16 percent of all energy consumed in 2015, compared with 22.6 percent in 2008. Consumption of renewable energy climbed to 9.8 percent from 7.3 percent.

The expansion of the renewable energy sector was driven by a number of factors including cost reductions associated with technological improvements as well as policy support in the form of tax breaks, but the low-interest rate environment undoubtedly contributed to the acceleration of the low-carbon transition.

Will the music stop?

The Fed has been able to keep the time value of money at record low levels for so long thanks to persistently low inflation. If inflation begins to accelerate as economic growth increases, the Fed no longer has that ability, and the upcoming rate rise will be just the beginning. That will begin to shift the valuations of high- and low-carbon projects, making the former a bit more attractive, the latter a bit less so.

But a quarter-point increase won’t change valuations much. For now, the low interest rates will continue to favor long-term sustainable projects that will help us reach the Paris targets, while discouraging unsustainable ones that become unprofitable once budgeting analyses consider the likely future implementation of carbon taxes and new emissions regulations.

If we do reach those targets, we would have the Fed and the markets to thank – and not Congress or Trump – for a successful transition to a low-carbon economy.

Author: Assistant Professor of Finance, St. Joseph’s University

Fintech – What Are The Risks?

Fed Governor Lael Brainard spoke on “The Opportunities and Challenges of Fintech” and highlighted the tension between the lightning pace of development of new products and services being brought to market–sometimes by firms that are new or have not historically specialized in consumer finance–and the duty to ensure that important risks around financial services and payments are addressed.The key challenge for regulatory agencies is to create the right balance.

Fintech has the potential to transform the way that financial services are delivered and designed as well as the underlying processes of payments, clearing, and settlement. The past few years have seen a proliferation of new digitally enabled financial products and services, in addition to new processes and platforms. Just as smartphones revolutionized the way in which we interact with one another to communicate and share information, fintech may impact nearly every aspect of how we interact with each other financially, from payments and credit to savings and financial planning. In our continuously connected, on-demand world, consumers, businesses, and financial institutions are all eager to find new ways to engage in financial transactions that are more convenient, timely, secure, and efficient.

In many cases, fintech puts financial change at consumers’ fingertips–literally. Today’s consumers, particularly millennials, are accustomed to having a wide range of applications, options, and information immediately accessible to them. Almost every type of consumer transaction–ordering groceries, downloading a movie, buying furniture, or arranging childcare, to name a few–can be done on a mobile device, and there are often multiple different applications that consumers can choose for each of these tasks based on their preferences. It seems inevitable for this kind of convenience, immediacy, and customization to extend to financial services. Indeed, according to the Federal Reserve Board’s most recent survey of mobile financial services, fully two-thirds of consumers between the ages of 18 and 29 having a mobile phone and a bank account use mobile banking.

New fintech platforms are giving consumers and small businesses more real-time control over their finances. Once broad adoption is achieved, it is technologically quite simple to conduct cashless person-to-person fund transfers, enabling, among other things, the splitting of a check after a meal out with friends or the sending of remittances quickly and cheaply to friends or family in other countries. Financial management tools are automating savings decisions based on what consumers can afford, and they are helping consumers set financial goals and providing feedback on expenditures that are inconsistent with those goals. In some cases, fintech applications are automatically transferring spare account balances into savings, based on monthly spending and income patterns, effectively making savings the default choice. Other applications are providing consumers with more real-time access to earnings as they are accrued rather than waiting for their regular payday. This service may be particularly valuable to the nearly 50 percent of adults with extremely limited liquid savings. It is too early to know what the overall impact of these innovations will be, but they offer the potential to empower consumers to better manage cash flow to reduce the need for more expensive credit products to cover short-term cash needs.

One particularly promising aspect of fintech is the potential to expand access to credit and other financial services for consumers and small businesses. By reducing loan processing and underwriting costs, online origination platforms may enable financial services providers to more cost effectively offer smaller-balance loans to households and small businesses than had previously been feasible. In addition, broader analysis of data may allow lenders to better assess the creditworthiness of potential borrowers, facilitating the responsible provision of loans to some individuals and firms that otherwise would not have access to such credit. In recent years, some innovative Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) have developed partnerships with online alternative lenders, with the goal of expanding credit access to underserved small businesses.

The challenge will be to foster socially beneficial innovation that responsibly expands access to credit for underserved consumers and small businesses, and those who otherwise would qualify only for high-cost alternatives. It would be a lost opportunity if, instead of expanding access in a socially beneficial way, some fintech products merely provided a vehicle to market high-cost loans to the underserved, or resulted in the digital equivalent of redlining, exacerbating rather than ameliorating financial access inequities.

We are also monitoring a growing fintech segment called “regtech” that aims to help banks achieve regulatory compliance more effectively. Regtech firms are designing new tools to assist banks and other financial institutions in addressing regulatory compliance issues ranging from onboarding new customers to consumer protection to payments and governance. Many of the current solutions are focused on Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) regulatory requirements, including know-your-customer (KYC) and suspicious activity reporting requirements. The solutions utilize new technologies and data-analytic techniques that may reduce the costs and time needed for banks to identify and assess customers’ money-laundering and terrorist-financing risks. However, it is too early to tell the degree to which innovative approaches to customer due diligence, such as KYC utilities, will deliver efficiency gains such as those outlined in the recent Bank for International Settlements Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures report on correspondent banking.

Ensuring Risks Are Managed and Consumers Are Protected

While financial innovation holds promise, it is crucial that financial firms, customers, regulators, and other stakeholders understand and mitigate associated risks. There is a tension between the lightning pace of development of new products and services being brought to market–sometimes by firms that are new or have not historically specialized in consumer finance–and the duty to ensure that important risks around financial services and payments are addressed. Firms need to ensure that they are appropriately controlling and mitigating both risks that are unique to fintech as well as risks that exist independently of new technologies.

For example, some fintech firms are exploring the use of nontraditional data in underwriting and pricing credit products. While nontraditional data may have the potential to help evaluate consumers who lack credit histories, some data may raise consumer protection concerns. Nontraditional data, such as the level of education and social media usage, may not necessarily have a broadly agreed upon or empirically established nexus with creditworthiness and may be correlated with characteristics protected by fair lending laws. To the extent that the use of this type of data could result in unfairly disadvantaging some groups of consumers, it requires careful review to ensure legal compliance. In addition, while consumers generally have some sense of how their financial behavior affects their traditional credit scores, alternative credit scoring methods present new challenges that could raise questions of fairness and transparency. It may not always be readily apparent to consumers, or even to regulators, what specific information is utilized by certain alternative credit scoring systems, how such use impacts a consumer’s ability to secure a loan or its pricing, and what behavioral changes consumers might take to improve their credit access and pricing.

Similarly, fintech innovations that rely on data sharing may create security, privacy, and data-ownership risks, even as they provide increased convenience to consumers. Recent examples of large-scale fraud and cybersecurity breaches have illustrated the significance of possible security risks. As the data sets that financial institutions utilize expand beyond traditional consumer credit histories, data privacy will become a growing concern, as will data ownership and whether or not the consumer has any say over how these data are used and shared or whether he or she can review it for accuracy. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau recently issued a request for information to better understand the benefits and risks associated with new financial services that rely on access to consumer financial accounts and account-related information.

In addition to the risks I have outlined that are specific to new financial technologies, firms also must control for risks that have always been present, even in brick-and-mortar financial institutions. For example, risks around the BSA and Anti-Money Laundering rules cut across all segments and all portfolios. Similarly, firms must monitor credit and liquidity risks of loans acquired or processed via fintech platforms, especially given that these products have not been tested over an economic cycle.

Furthermore, as a general rule, the introduction of new products or services typically involves heightened risks as a financial institution enters into new areas with which it may not have experience or that may not be consistent with its overall business strategy and risk tolerance. Banks collaborating with fintech firms must control for the risks associated with the associated new products, services, and third-party relationships. When incorporating innovation that is consistent with a bank’s goals and risk tolerance, bankers will need to consider which model of engagement is most appropriate in light of their business model and risk-management infrastructure, manage any outsourced relationships consistent with supervisory expectations, ensure that regulatory compliance considerations are included in the development of new products and services, and have strong fallback plans in place to limit the risks associated with products and partners that may not survive.

With the growing number of partnerships between banks and fintech companies, we often receive questions about the applicability of our vendor risk-management guidance. We are actively reviewing our guidance to determine whether any adjustments or clarifications may become appropriate in the context of these arrangements. We hear concerns from community bankers in particular about their internal capacity to undertake the requisite due diligence and ongoing vendor management on their own, especially with much larger vendors, and questions about whether the interagency service providers supervision program might be relevant in this context. We are thinking about whether changes brought about by fintech and fintech partnerships may warrant consideration of any changes to the interagency supervision program for service providers.

Regulatory Engagement

I believe that the Federal Reserve is well-positioned to help shape this innovation as it develops, and it is important that we be clear about our expectations and mindful of the possible effects of our actions. The policy, regulatory, and supervisory decisions made by the Federal Reserve and other financial regulators can impact the ways in which new financial technologies are developed and implemented, and ultimately how effective they are. It is critical that fintech firms and financial institutions comply with all applicable legal protections and obligations. At the same time, it is important that regulators and supervisors not impose undue burdens on financial innovations that would provide broad social benefits responsibly. An unduly rigid regulatory or supervisory posture could lead to unintended consequences, such as the movement of innovations outside of the regulated banking industry, potentially creating greater risks and less transparency.

The rapid pace of change and the large number of actors–both banks and nonbanks–in fintech raise questions about how to effectively conduct our regulatory and supervisory activities. In one sense, regulators’ approach to fintech should be no different than for conventional financial products or services. The same basic principles regarding fairness and transparency should apply regardless of whether a consumer obtains a product through a brick-and-mortar bank branch or an online portal using a smartphone. Indeed, the same consumer laws and regulations that apply to products offered by banks generally apply to nonbank fintech firms as well, even though their business models may differ. However, the application of laws and regulations that were designed based on traditional financial products and delivery channels may give rise to complex or novel issues when applied to new products or new delivery channels. As a result, we are committed to regularly engage with firms and the technology to develop a shared understanding of these issues as they evolve.

Fundamentally, financial institutions themselves are responsible for providing innovative financial services safely. Financial services firms must pair technological know-how and innovative services with a strong compliance culture and a thorough knowledge of the important legal and compliance guardrails. While “run fast and break things” may be a popular mantra in the technology space, it is ill-suited to an arena that depends on trust and confidence. New entrants need to understand that the financial arena is a carefully regulated space with a compelling rationale underlying the various rules at play, even if these are likely to evolve over time. There is more at stake in the realm of financial services than in some other areas of technological innovation. There are more serious and lasting consequences for a consumer who gets, for instance, an unsustainable loan on his or her smartphone than for a consumer who downloads the wrong movie or listens to a bad podcast. At the same time, regulators may need to revisit processes designed for a brick-and-mortar world when approaching digital finance. To ensure that fintech realizes its positive potential, regulators and firms alike should take a long view, with thoughtful engagement on both sides.

When we look back at times of financial crisis or missteps, we frequently find that a key cause was elevating short-term profitability over long-term sustainability and consumer welfare. It was not long ago that so-called exotic mortgages originally designed for niche borrowers became increasingly marketed to low- and moderate-income borrowers who could not sustain them, ultimately with disastrous results. In addition to the financial consequences for individual consumers, the drive for unsustainable profit can contribute to distrust in the financial system, which is detrimental to the broader economy. It is critical that firms providing financial services consider the long-term social benefit of the products and services they offer. Concerns regarding long-term sustainability are magnified in situations where banks may bear credit or other longer-term operational risks related to products delivered by a fintech firm. One useful question to ask is whether a product’s success depends on consumers making ill-informed choices; if so, or if the product otherwise fails to provide sufficient value to consumers, it is not going to be seen as responsible and may not prove sustainable over time.

The key challenge for regulatory agencies is to create the right balance. Ultimately, regulators should be prepared to appropriately tailor regulatory or supervisory expectations, to the extent possible within our respective authorities, to facilitate fintech innovations that produce benefits for consumers, businesses, and the financial system. At the same time, any contemplated adjustments must also appropriately manage corresponding risks.

US Household Debt Hits $12.4 Trillion

The latest just released Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit from the New York Fed showed a small increase in overall debt in the third quarter of 2016, prompted by gains in non-housing debt, and new all time highs in student loans which hit $1.279 trillion, rising $20 billion in the quarter.11.0% of aggregate student loan debt was 90+ days delinquent or in default at the end of 2016 Q3.

Total household debt rose $63 billion in the quarter to $12.35 trillion, driven by a $32 billion increase in auto loans, which also hit a record high of $1.14 trillion. 3.6% of auto loans were 90 or more days delinquent.

Mortgage balances continued to grow at a sluggish pace since the recession while auto loan balances are growing steadily, and hit a new all time high of $1.14 trillion.

What was most troubling, however, is that delinquencies for auto loans increased in the third quarter, and new subprime auto loan delinquencies have not hit the highest level in 6 years.

The rise in auto loans, a topic closely followed here, has been fueled by high levels of originations across the spectrum of creditworthiness, including subprime loans, which are disproportionately originated by auto finance companies.

Disaggregating delinquency rates by credit score reveals signs of distress for loans issued to subprime borrowers—those with a credit score under 620.

To address the troubling surge in auto loan delinquencies, the NY Fed Liberty Street Economics blog posted an analysis of the latest developments in the sector. This is what it found.

Subprime Auto Debt Grows Despite Rising Delinquencies

The rise in auto loans has been fueled by high levels of originations across the spectrum of creditworthiness, including subprime loans, which are disproportionately originated by auto finance companies. Disaggregating delinquency rates by credit score reveals signs of distress for loans issued to subprime borrowers—those with a credit score under 620. In this post we take a deeper dive into the observed growth in auto loan originations and delinquencies. This analysis and our Quarterly Report are based on the New York Fed’s Consumer Credit Panel, a data set drawn from Equifax credit reports.

Originations of auto loans have continued at a brisk pace over the past few years, with 2016 shaping up to be the strongest of any year in our data, which begin in 1999. The chart below shows total auto loan originations broken out by credit score. The dollar volume of originations has been high for all groups of borrowers this year, with the quarterly levels of originations only just shy of the highs reached in 2005. The overall composition of both originations and outstanding balances has been stable.

As we noted in an earlier blog post, one feature of our data set is that it enables us to infer whether auto loans were made by a bank or credit union, or by an auto finance company. The latter are typically made through a car manufacturer or dealer using Equifax’s lender classification. Although it remains true that banks and credit unions comprise about half of the overall outstanding balance of newly originated loans, the vast majority of subprime loans are originated by auto finance companies. The chart below disaggregates the $1.135 trillion of outstanding auto loans by credit score and lender type, and we see that 75 percent of the outstanding subprime loans were originated by finance companies.Auto

In the chart below, auto loan balances broken out by credit score reveal that balances associated with the most creditworthy borrowers—those with a score above 760 (in gray below)—have steadily increased, even through the Great Recession. Meanwhile, the balances of the subprime borrowers (in light blue below), contracted sharply during the recession and then began growing in 2011, surpassing their pre-recession peak in 2015.

Delinquency Rates

Auto loan delinquency data, reported in our Quarterly Report, show that the overall ninety-plus day delinquency rate for auto loans increased only slightly in 2016 through the end of September to 3.6 percent. But the relatively stable delinquency rate masks diverging performance trends across the two types of lenders. Specifically, a worsening performance among auto loans issued by auto finance companies is masked by improvements in the delinquency rates of auto loans issued by banks and credit unions. The ninety-plus day delinquency rate for auto finance company loans worsened by a full percentage point over the past four quarters, while delinquency rates for bank and credit union auto loans have improved slightly. An even sharper divergence appears in the new flow into delinquency for loans broken out by the borrower’s credit score at origination, shown in the chart below. The worsening in the delinquency rate of subprime auto loans is pronounced, with a notable increase during the past few years.

It’s worth noting that the majority of auto loans are still performing well—it’s the subprime loans that heavily influence the delinquency rates. Consequently, auto finance companies that specialize in subprime lending, as well as some banks with higher subprime exposure are likely to have experienced declining performance in their auto loan portfolios.

Conclusion

The data suggest some notable deterioration in the performance of subprime auto loans. This translates into a large number of households, with roughly six million individuals at least ninety days late on their auto loan payments. Even though the balances of subprime loans are somewhat smaller on average, the increased level of distress associated with subprime loan delinquencies is of significant concern, and likely to have ongoing consequences for affected households.

Is Financial Risk Socially Determined?

From The St. Louis On The Economy Blog.

The authors of the In the Balance—Senior Economic Adviser William Emmons, Senior Analyst Lowell Ricketts and Intern Tasso Pettigrew, all with the St. Louis Fed’s Center for Household Financial Stability—found that eliminating so-called “bad choices” and “bad luck” reduced the likelihood of serious delinquency. With the exception of Hispanic families, this did not get rid of disparities in delinquency risk relative to the lower-risk reference group.

However, this exercise was based on the idea that the young (or less-educated or nonwhite) families’ financial and personal choices, behavior and exposure to luck could conform to those of the old (or better-educated or white) families. The authors suggested that such an approach may not be realistic.

A Lack of Choice?

“We believe a more realistic starting point for assessing the mediating role of financial and personal choices, behavior and luck in determining delinquency risk is a family’s peer group,” the authors wrote. They looked at how an individual family’s circumstances differ from its peer group, hoping to capture the “gravitational” effects of the peer group.

The odds are similar to those that were not adjusted, as seen in the figures below. (For 95 percent confidence intervals, see “Choosing to Fail or Lack of Choice? The Demographics of Loan Delinquency.”)

In particular, they examined how a randomly chosen family fared against the average of its peer group, such as how much debt a young black or Hispanic family with at most a high school diploma has compared to the family’s peer-group norm.

“We assume that the distinctive financial or personal traits associated with a peer group ultimately derive from the structural, systemic or historical circumstances and experiences unique to that demographic group,” the authors wrote.

When assuming that individual families’ choices extend only to deviations from peer-group averages, the authors estimated that:

- A family headed by someone under 40 years old is 5.8 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a family headed by someone 62 years old or more.

- Middle-aged families (those with a family head aged 40 to 61 years old) are 4.2 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as old families.

- A family headed by someone with at most a high school diploma is 1.8 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a family headed by someone with postgraduate education.

- A family headed by someone with at most a four-year college degree is 1.4 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a family headed by someone with postgraduate education.

- A black family is 2.0 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a white family.

- A Hispanic family is 1.2 times as likely to become seriously delinquent as a white family.

These demographic groups still appear to have a higher delinquency risk than older, better-educated and white families. This suggests that younger, less-educated and nonwhite families may have little choice in the matter.

“The striking differences in delinquency risk across demographic groups cannot be explained simply by referring to differences in risk preferences,” Emmons, Ricketts and Pettigrew wrote. “Instead, we suggest that deeper sources of vulnerability and exposure to financial distress are at work.”

The authors also concluded: “Families with ‘delinquency-prone’ demographic characteristics—being young, less-educated and nonwhite—did not choose and cannot readily change these characteristics, so we should refrain from adding insult to injury by suggesting that they simply have brought financial problems on themselves by making risky choices.”

Each family was assigned to one of 12 peer groups, which were defined by age (young, middle-aged or old), race or ethnicity (white or black/Hispanic) and education (at most a high school diploma or any college up to a graduate/professional degree).

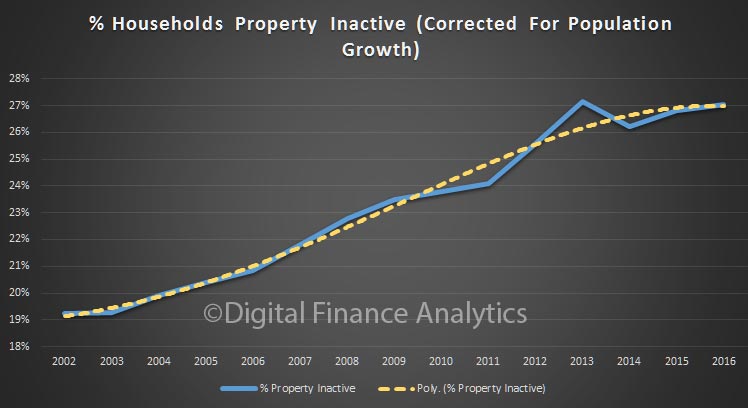

The Problem Of Home Ownership

The proportion of households in Australia who own a property is falling, more a renting, or living with family or friends. We track those who are “property inactive”, and the trend, over time is consistent, and worrying.

It is harder to buy a property today, thanks to high prices, flat incomes and higher credit underwriting standards. Whilst some will go direct to the investment property sector (buying a cheaper place with the help of tax breaks); many are excluded.

It is harder to buy a property today, thanks to high prices, flat incomes and higher credit underwriting standards. Whilst some will go direct to the investment property sector (buying a cheaper place with the help of tax breaks); many are excluded.

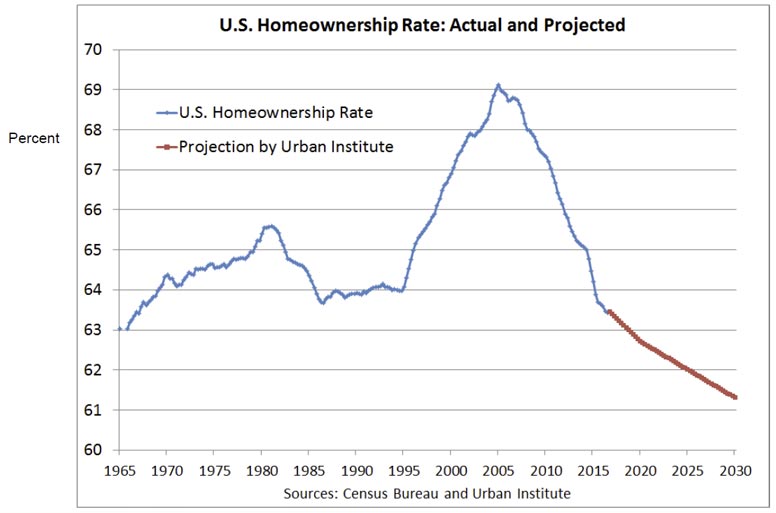

This exclusion is not just an Australian phenomenon. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis just ran an interesting session on “Is Homeownership Still the American Dream?” In the US the homeownership rate has been declining for a decade. Is the American Dream slipping away? They presented this chart:

A range of reasons were discussed to explain the fall. Factors included: the Great Recession and foreclosure crisis; tougher to get a mortgage now (but probably too easy before the crash); older, more diverse American population; stagnation of middle-class incomes; delayed marriage and childbearing; student loans and growing attractiveness of renting for some.

A range of reasons were discussed to explain the fall. Factors included: the Great Recession and foreclosure crisis; tougher to get a mortgage now (but probably too easy before the crash); older, more diverse American population; stagnation of middle-class incomes; delayed marriage and childbearing; student loans and growing attractiveness of renting for some.

Yet, there is very little association between local housing-market conditions experienced during the recent boom-bust cycle and changes in attitudes toward homeownership. The desire to be a homeowner remains remarkably strong across all age, education, racial and ethnic groups. To remain a viable option for all groups, homeownership must become more affordable and sustainable.

They went on to discuss how to address the gap.

Tax benefits are “demand distortions.” Most economists agree that tax preferences for shelter (especially homeownership) push up prices: Benefits are “capitalized” into price or rent. Tax benefits of $150 bn. annually are skewed toward homeowners in high tax brackets via tax deductibility or exclusion. Tax changes likely in 2017—lower rates and higher standard deduction—will reduce tax benefits for homeownership, perhaps slowing or reducing house prices.

There also are “supply distortions” in housing that push up prices/rents. Land-use regulations/restrictive building codes increase construction costs, making housing less plentiful and less affordable. Local governments could reduce these constraints, and housing of all types and tenures would become cheaper.

Tightening Underwriting Standards. Unsuccessful homeownership experiences stem from shocks (job loss, divorce, sickness) that expose unsustainable financing—i.e., too much debt and too little homeowners’ equity (HOE). Reduce the risk of financial distress and losing a home by encouraging or requiring higher HOE and less debt. This would increase the age of first-time homebuyers and reduce homeownership but also reduce the risk of foreclosures.

You can watch the video here. But I think there are some important insights which are applicable to the local scene here. Not least, you cannot avoid the discussion around tax – both negative gearing and capital gains benefits need to be on the table. Supply side initiatives alone will not solve the problem.