U.S. non-bank mortgage lenders may face further margin pressure as interest rates continue to rise owing to higher funding costs relative to banks with lower-cost, stable depository funding, Fitch Ratings says.

Profitability metrics for non-bank mortgage lenders are generally weak, with expenses outstripping net revenues by approximately 21% across the five public non-bank mortgage companies for the 4.5-year period ending June 30, 2018.

We expect consolidation to continue as a result of weak profitability, with non-bank lenders seeking scale efficiencies to combat rising rates, persistently high technology and regulatory compliance costs, and declining refinancing activity. That said, non-bank lenders with multiple origination channels and established mortgage servicing platforms that generate higher fee income and more sustainable earnings should be better positioned for the shifting trends of the interest rate and economic cycles. These lenders are generally less exposed to cyclical swings in the mortgage market, as the complementary nature of origination and servicing businesses can serve as a natural hedge, reducing earnings volatility.

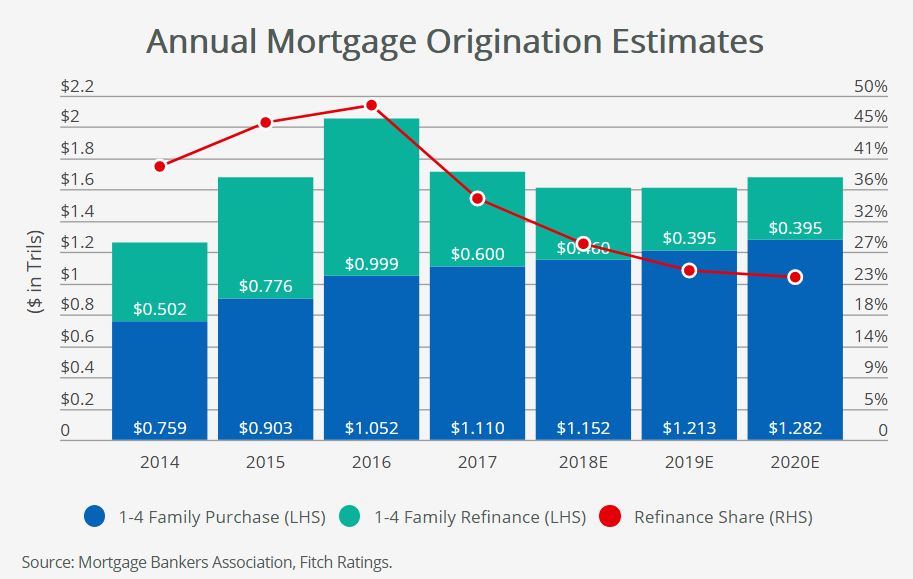

Aside from driving funding costs higher, Fitch also sees rising interest rates as a headwind to origination volumes, which could further pressure profitability in the medium term. Forecasts by the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) call for originations of $1.6 trillion annually from 2018-2020, down 6% from 2017 levels. Refinancings should drop to 24% of originations by 2020, down from 49% in 2016, in the face of rising rates, according the MBA.

Positively, mortgage servicing right (MSR) valuations generally increase with rising rates and economic growth, as prepayments fall and default risk lessens. Reflecting these dynamics, MSR valuations have increased in recent years, averaging 104bps of the unpaid principal balance of servicing portfolios for the five public non-bank mortgage companies.

Ratings assigned to non-bank mortgage servicers are typically in the ‘B’ to ‘BB’ rating categories, reflecting the highly cyclical and monoline nature of the business, valuation volatility associated with MSRs, elevated legislative and regulatory scrutiny, weak earnings profiles and reliance on short-term wholesale funding sources.