So Australia dodged the “recession bullet” thanks to a rebound in the December quarter. It was helped by resources sector income from higher prices especially coal and iron ore, households who raided their savings to lift expenditure over the Christmas season, and Government sector infrastructure spending.

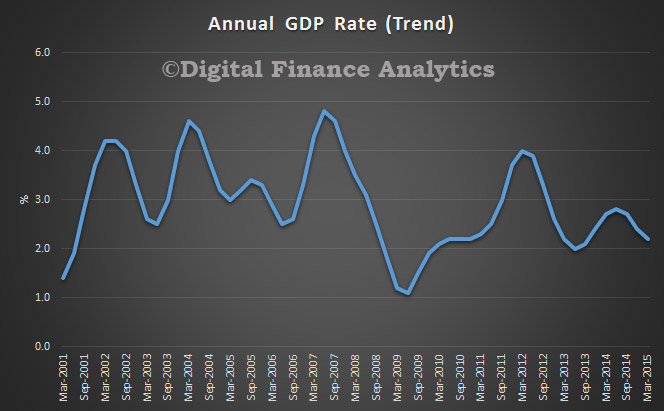

But the underlying contribution from business excluding resources looks weak, and it seems the whole confection of managing the mining sector slow-down by stoking the housing sector is to be questioned. Growth at 2.4 per cent is lower than the 3 per cent plus target. Low interest rates are not encouraging business to invest. Even lower rates won’t help. Low wage growth is part of the problem, but it is a symptom of underlying disease.

But the underlying contribution from business excluding resources looks weak, and it seems the whole confection of managing the mining sector slow-down by stoking the housing sector is to be questioned. Growth at 2.4 per cent is lower than the 3 per cent plus target. Low interest rates are not encouraging business to invest. Even lower rates won’t help. Low wage growth is part of the problem, but it is a symptom of underlying disease.

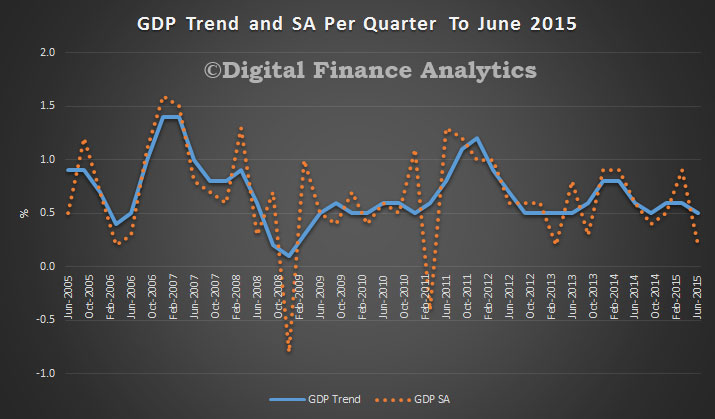

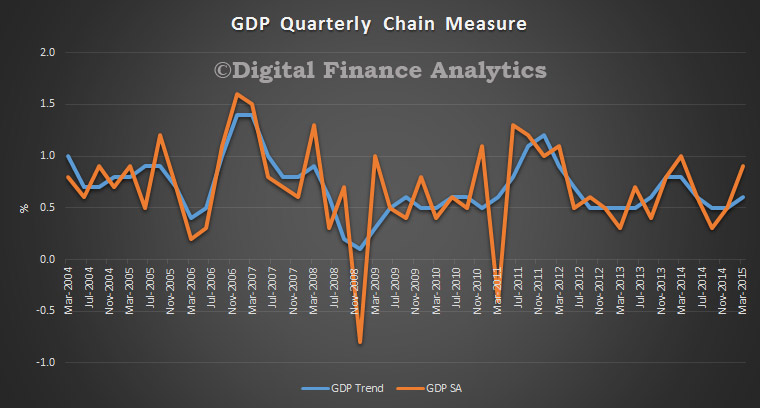

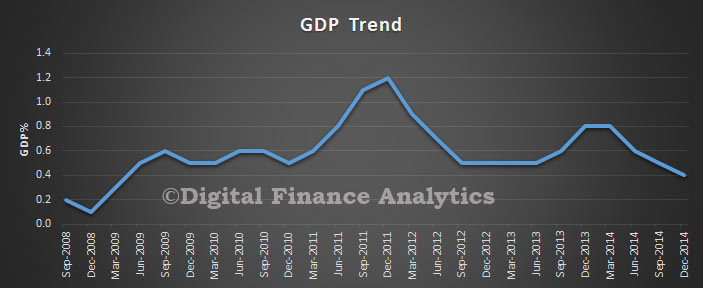

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) shows that the Australian economy recorded broad-based growth of 1.1 per cent in seasonally adjusted chain volume terms in the December quarter 2016, a rebound from the previous quarter’s decline of 0.5 per cent, Australia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has now grown 2.4 per cent through the year.

Growth was recorded in 15 out of 20 industries. Strongest growth was observed in Mining, Agriculture, forestry and fishing, and Professional scientific and technical services, each industry contributed 0.2 percentage points to GDP growth.

Household final consumption expenditure contributed 0.5 percentage points to GDP growth. Net exports contributed 0.2 percentage points. Public and private capital formation both contributed 0.3 percentage points this quarter after both detracted from GDP growth last quarter.

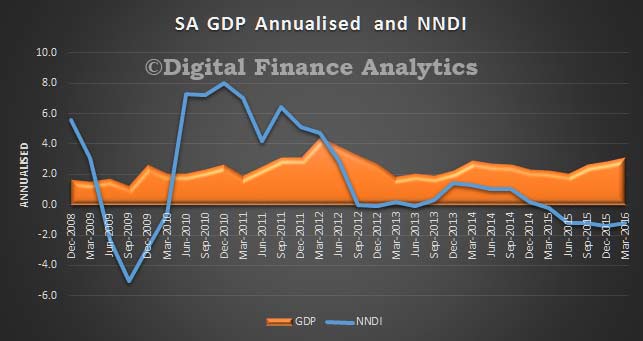

The Terms of trade grew by 9.1 per cent in the December quarter due to strong price rises in Coal and Iron ore. The terms of trade is now 15.6 per cent higher than December quarter 2015. Nominal GDP grew by 3.0 per cent to be 6.1 per cent higher through the year. Real net national disposable income increased by 2.9 per cent for the quarter.

The strength in commodity prices helped drive a 16.5 per cent increase in Private non-financial corporation’s Gross operating surplus. Compensation of employees decreased 0.5 per cent for the quarter to be 1.5 per cent higher through the year. This is in line with the subdued wage price index (1.9 per cent through the year) and employment growth (0.7 per cent through the year) previously published by the ABS.

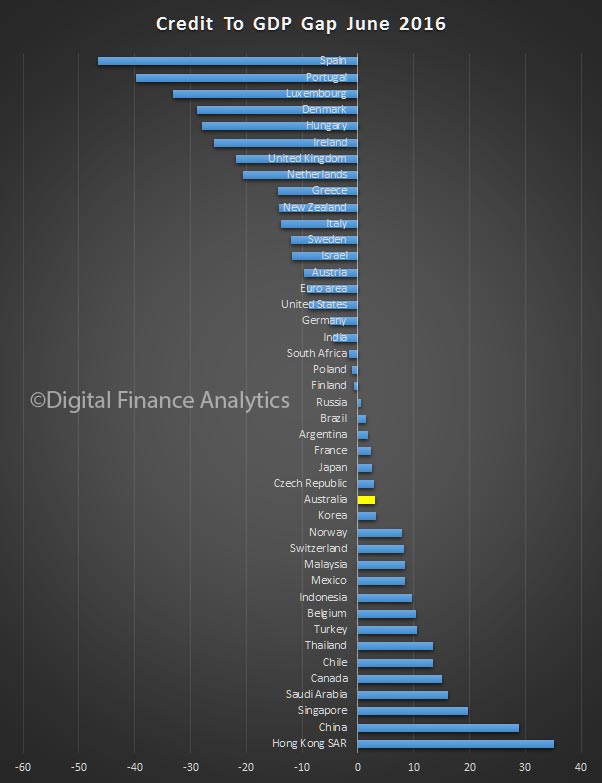

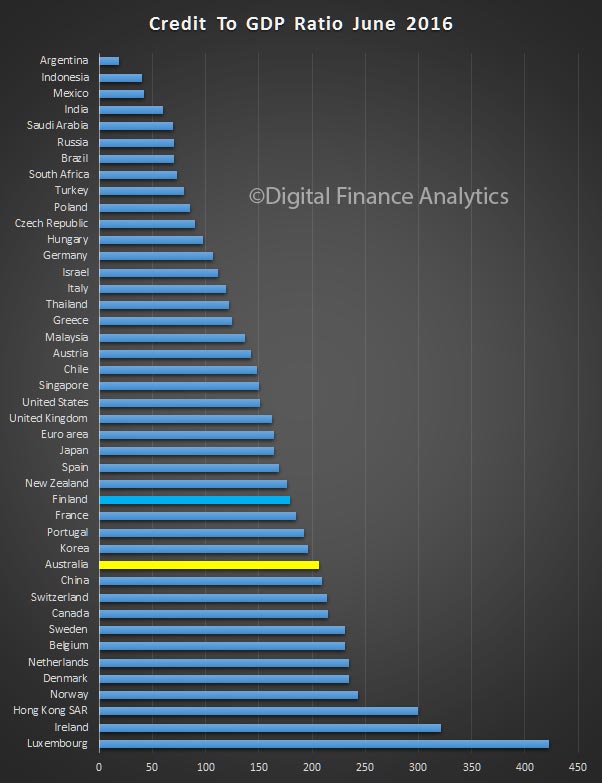

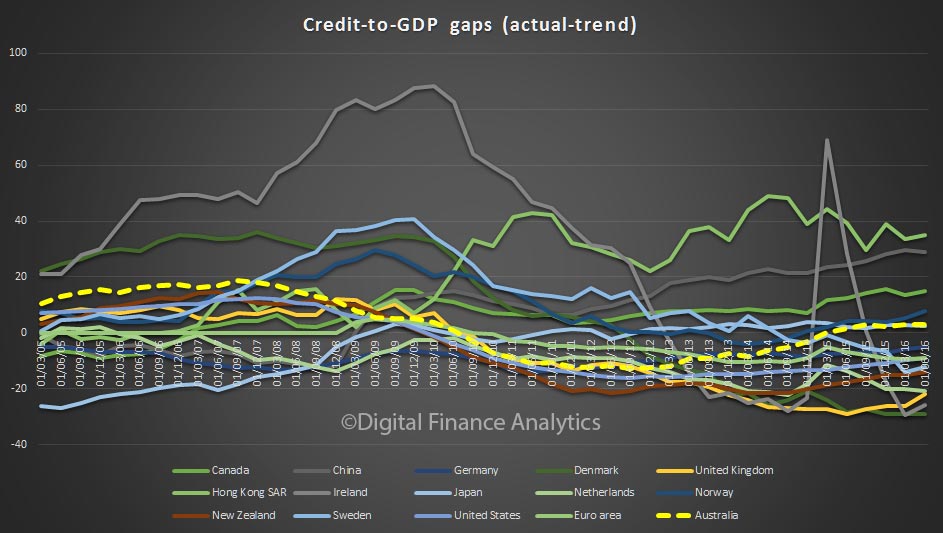

The BIS says

The BIS says