The Greek people have voted, saying a resounding No to the terms of the bailout deal offered by their international creditors. What will this mean for Greece, the euro and the future of the EU? Our experts explain what happens next.

Costas Milas, Professor of Finance, University of Liverpool

Greek voters have confirmed their support for their prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, who now has the extremely challenging task of renegotiating a “better” deal for his country.

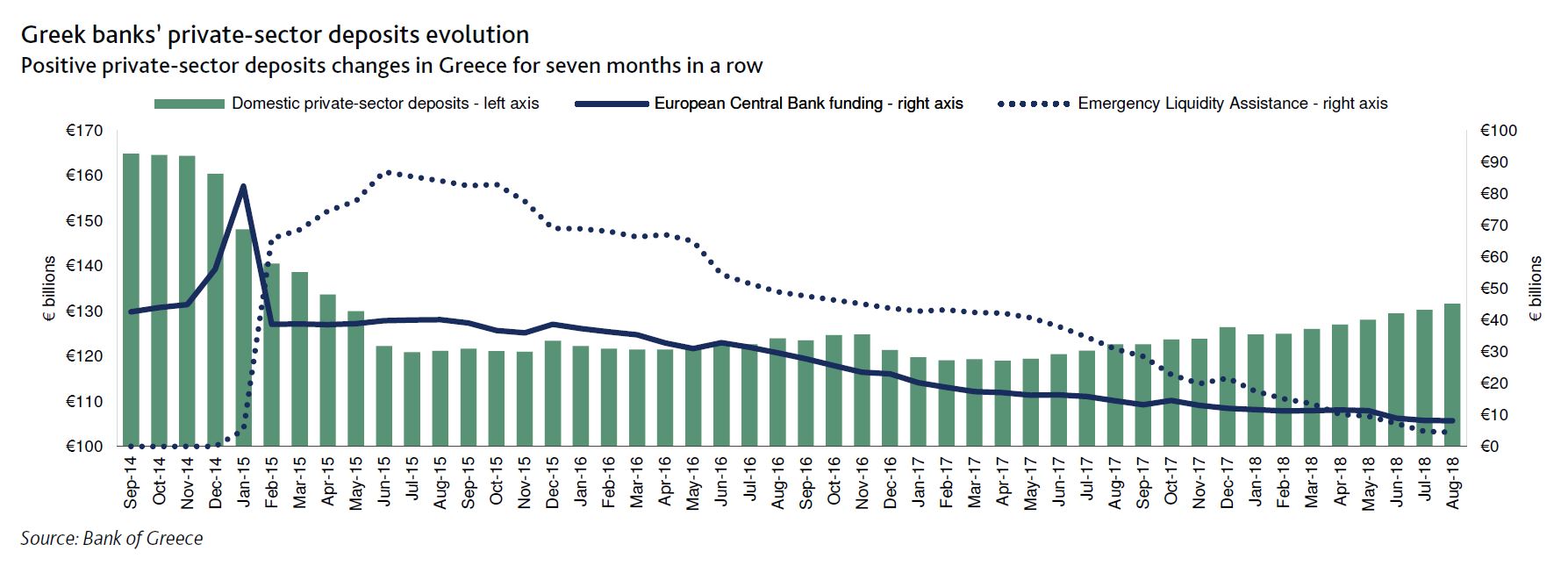

Nevertheless, time is very short. Greece’s economic situation is critical. On July 2, Greek banks reportedly had only €500m in cash reserves. This buffer is not even 0.5% of the €120 billion deposits that Greek citizens have to their names. It is only capital controls preventing Greek banks from collapsing under the strain of withdrawal.

Basic mathematical calculations reveal how desperate the situation is. There are roughly 9.9m registered Greek voters. Assume that – irrespective of whether they voted Yes or No – some 2.8m voters (that is, a very modest 28.2% of the total number of registered voters) decide to withdraw their daily limit of €60 from cash machines on Monday morning. Following this pattern, banks will run out of cash in three days and therefore collapse (note: 3 x 2.8m x 60 ≈ 500m).

There is therefore very little time for the Greek government to strike the deal with their creditors that will instantaneously give the ECB the “green light” to inject additional Emergency Liquidity Assistance (ELA) to Greek banks to support their cash buffer and save them from collapse. In other words, Greece does not have the luxury of playing “hard ball” with its creditors. An agreement has to be imminent.

Financial markets, expected to start very nervously on Monday morning, will probably stay relatively calm as the reality of the economic situation spelled out above is more likely than not to lead to some sort of agreement (provided, of course, that Greece’s creditors will listen to Tsipras). Whether this agreement is good for the Greeks, this is an entirely different story.

Richard Holden, Professor of economics, UNSW Australia

By calling this referendum and shutting off negotiations for nearly a week, the Syriza party has brought the Greek banking system very close to insolvency. Greece can’t print euros so Greek banks will soon need to issue IOUs, or the demand for money will not be met, leading to utter chaos. Who will accept these? How will they be valued? These are big, scary questions to which nobody knows the answer.

By voting No, Greece has tied the hands of European Central Bank president Mario Draghi. As a matter of politics there’s not much he can do in the short-term and with Greek banks insolvent he may not be able to do anything simply as a matter of law.

At least one if not all the major Greek banks are likely to fail early this week. When this happens, the Greek economy will essentially come to a halt. Nobody knows what will happen, but it surely won’t be good.

The other depressing consequence of the No vote is that Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis’s promise to resign if his fellow citizens voted Yes will not come about. It has been abundantly clear that Syriza representatives have been miles out of their depth from the time they took office.

Everyone with real knowledge and experience of financial markets and liquidity crises told them to stop playing chicken with the IMF and ECB. They should start listening immediately.

George Kyris, Lecturer in International and European Politics, University of Birmingham

A historic referendum for Greece and Europe tells a very interesting story. While results indicate that a sizeable 61% rejected existing policies towards the Greek crisis, polls have consistently shown that the majority of Greeks want to remain in the eurozone. This exposes the success of Syriza based on its populism, which has allowed Greeks to think that they can stay a credible member of the EU, while at the same time taking unilateral decisions and refusing to recognise the obligations of their eurozone membership.

This not only creates unrealistic expectations but it is also a very sad result for the relationship between the EU and its citizens, which, once again, falls victim to national governments’ short-term strategies. In this climate of unrealistic expectations, the Greek government embarks on a mission impossible to secure a better deal for the country, where economic, political and social peace has been seriously undermined in the past few months and week especially.

The first reactions of Greece’s EU partners to the No vote are far from positive.

In his address after the referendum, Alexis Tsipras indicated the formation of an ad hoc national council with the participation of major political parties to prepare the negotiation strategy. The next few days will show if a more united Greek front is possible and capable of improving things for the crisis-hit country.

Ross Buckley, Professor, Faculty of Law at UNSW Australia

The Greek people have decisively voted No to more austerity imposed from Frankfurt. This is unsurprising. Voters rarely vote for higher taxes and lower pensions. However other polls reveal clearly that the Greek people overwhelmingly also want to retain the Euro. So this is one giant gamble. The Greeks are betting that the potential damage to other countries, especially Spain and Italy, and thus to the very fabric of the Euro, is simply too great for the Eurozone to eject Greece.

When voting on Sunday most Greeks probably felt they were reclaiming control of their own economy. However, paradoxically, the No vote has done the opposite. Greece’s short to medium term economic future is now in the hands of others, particularly Germany and France.

Greek banks today are all but out of Euros. Normally in this situation a nation’s central bank simply prints more currency. Greece can’t do that, as no one country controls production of the Euro. So the options over the next month or so seem to be that either Germany, France and the European Central Bank blink, and extend more credit to Greece, or Greece’s financial system will cease functioning and ultimately it will be forced to print drachma.

Remy Davison, Jean Monnet Chair in Politics and Economics at Monash University

With eyes wide shut, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras has sent his country to the wall.

The “OXI” voters in Athens last night were in full party mode. But in the cold, harsh light of day, the depressingly-painful hangover begins.

61% of voters will wish they didn’t drink so much of the OXI Kool-Aid. Especially when the realisation hits voters that they can only get €60 out of the ATM. Or €50, as €20 notes are now scarce.

The next hurdle for Athens is ominous. The government has a $3.5 billion repayment due to the ECB in mid-July. Defaulting on the 30 June IMF payment was not as serious as the media made out; the IMF default process is slow and ponderous. Conversely, the ECB controls Greece’s capital lifelines. Its emergency lending assistance (ELA) facility has kept Greek banks liquid up to this point. However, the ECB’s Governing Council and the Eurogroup ministers are unlikely to be sympathetic if Tsipras and Varoufakis attempt to renege on the ECB debt repayments.

A deal will ultimately be struck or Greek banks will not reopen without assistance from the ECB. Europe’s central bank will not refinance Greek banks endlessly, as the absence of capital controls before they were imposed on 29 June saw billions of euro offshored within days.

Tax evasion remains a systemic problem for Greece. A Swiss media source has reported that Athens is quietly offering amnesty from prosecution to Greek tax evaders, who have squirrelled away their euro in Swiss bank accounts, if they pay 21% tax.

A Grexit is still extremely unlikely. If there is one thing that government and opposition parties agree upon, it is that there will be no attempt to depart the eurozone. It is not in Greece’s interest, and there is no legal mechanism with which to do so.

An extra-legal attempt (i.e., outside the EU treaties) by a qualified or absolute majority of EU member governments to vote for Greece’s ejection from the eurozone would result in a Greek application to the European Court of Justice for an injunction. A hearing by the ECJ on an attempt to remove Greece from the eurozone could potentially take two years or more, given the complete absence of precedent and the considerable time and resources required to compile briefs for a case of such complexity. Financial commentators who believe in a high probability of a Grexit are either deluded, or have little comprehension of how the institutional mechanisms and procedures of the EU actually work.

The tragedy is that Tsipras and Varoufakis did not need initiate this crisis, as Greece and the IMF were only $400 million apart in their negotiations before the Greek government walked out. Tspiras and Varoufakis have spun the recent IMF report, which calls for debt restructuring, as somehow supporting their side of the story.

In reality, the IMF has been heavily critical of the Tsipras-Varoufakis government and its unwillingness to undertake the requisite, difficult structural reforms that Greece needs, including further privatisation, industry deregulation and competition policy reform, rigorous taxation restructuring in the Greek merchant shipping industry, and tackling offshore tax evasion. Why a far-left government in Greece wants to help rich Greeks to avoid tax defies logic.

In June, a reasonable compromise may have been reached between Athens and the Eurogroup. But it’s unlikely Euro Area ministers will have much sympathy to spare in the next round of negotiations.

Greeks may have voted with an overwhelming “OXI”, but it’s unlikely they realised they might also be voting for capital controls, insolvent banks and a financial system on the verge of meltdown.

Nikos Papastergiadis, School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne

A profound recognition has been given now, not just by economists, but by the people of Greece, that the economic policies pushed by the troika are counter-productive.

The government can now walk into negotiations in a strengthened position. They can honour their promises. They have no intention to leave the eurozone, let alone the EU, but can focus on a debt restructure, tackling tax evasion and modernising the state.

I expect some sort of financial resolution in the next 24-48 hours, because a move back to the drachma would be catastrophic.

When politicians in Europe say things like ‘It’s not a problem for us there is no risk of economic contagion,’ that is a profoundly immoral comment given there’s a real risk Europeans will die this winter as a result of their policies. Their sense of solidarity with the union is profoundly blinkered. The risk is not just economic contagion, it’s political contagion. They don’t want Syriza to be the example for other European governments. They wanted Greece to be humbled and crippled by these austerity measures. This divide and conquer attitude means there will be long-term political consequences.

I am so proud of the courage demonstrated by Greeks who have stood up in the face of their own oligarchs, who launched a smear campaign against the government, and said ‘enough is enough’.

James Arvanitakis, Professor in Cultural and Social Analysis at University of Western Sydney

The Greek people have shown overwhelming support for the Greek government and their stance against the so-called troika.

While most commentators may claim they suspected the outcome, I think those who are honest would say the decision was too close to call. The 61% vote in favour of the government does not indicate this, but the reality is the vast majority of Greeks did not know themselves what their vote would be.

In the end, the existential crisis of potentially leaving the Euro and even the European Union was usurped by the fact that they have had enough: enough of austerity that has driven the economy into the ground, enough of 25% unemployment and a lost generation of productivity with 50% youth unemployment, and enough of the troika and the bankers holding them to ransom. As one academic said to me when I was recently there:

“Who created the crisis and who pays for it? Like the GFC, it was those that lent the money, those that fudged the figures and those who have moved their money into offshore accounts. We lose our houses, they sip Retsina and watch sunsets on the islands.”

So what is next for the Greek people?

The obvious answer is uncertainty. But the uncertainty and potential for financial meltdown seems to have usurped the absolute hopelessness that is associated with ‘more of the same’.

Over the last five years we have seen the Greek government meet most of the austerity requests put forward by the troika. Economic theory tells us that in the “long run”, the austerity would work. For the Greek population however, the long run is too far away, unrealistic and a party trick they are no longer willing to fall for.

Greeks have said enough. They have decided it is better to reboot the economy and suffer the potential consequences than continue to see deeply flawed measures bring nothing but financial misery.

Over the next few days we will see continued celebrations. These will quickly disappear depending on the outcome of the negotiations. As I have written elsewhere, Greek society is fraying, how the negotiations go including a potential “Grexit” would determine just how far this unravelling goes.

The heartbreaking image of an elderly man, 77-year-old retiree Giorgos Chatzifotiadis, collapsed on the ground openly crying in despair outside a Greek bank, captured the attention of the world. It is a manifestation of what happens when economic policy and ideology is separated from the impacts on real people.

The “No” vote will restore the pride that has evaporated. But whether this pride turns into something productive or something that is a chauvinistic nationalism, no-one knows.