According to the ABS’ latest estimates, the total value of Australia’s assets as at end June 2014 was around $12½ trillion, or around $500,000 for each person living in Australia. After an adjustment is made for net foreign liabilities, the net asset position, or net wealth, was around $10 trillion, which is the equivalent to around six times Australia’s annual GDP.

The second observation is that, over recent decades, net wealth has increased at a faster rate than has GDP. Between 1989 and 2014, the nominal value of net wealth increased at an average pace of around 7 per cent per year, compared with an average increase in nominal GDP of around 6 per cent. While net wealth grew more slowly than GDP in the first half of the 1990s, for most of the time since it has grown more quickly than GDP.

The third observation relates to the composition of our national assets. Land is the asset class with the highest value. As at June 2014, it accounted for 34 per cent of the value of our national assets. This is followed by non-dwelling construction – offices, factories, infrastructure, etc. – which accounts for a further 18 per cent of total assets. And then overseas financial assets and the value of our dwellings each account for a little under 15 per cent of the national balance sheet. Intellectual property assets account for only around 2 per cent of the total.

The third observation relates to the composition of our national assets. Land is the asset class with the highest value. As at June 2014, it accounted for 34 per cent of the value of our national assets. This is followed by non-dwelling construction – offices, factories, infrastructure, etc. – which accounts for a further 18 per cent of total assets. And then overseas financial assets and the value of our dwellings each account for a little under 15 per cent of the national balance sheet. Intellectual property assets account for only around 2 per cent of the total.

The final and perhaps most interesting set of observations relate to how the structure of the balance sheet has changed through time.

The final and perhaps most interesting set of observations relate to how the structure of the balance sheet has changed through time.

One very clear trend has been a substantial increase in the value of our foreign financial assets and liabilities; both have increased much faster than net wealth. In effect, as we have become more globally integrated as a nation, there has been a grossing-up of our balance sheet with the rest of the world. Australians now hold many more overseas assets than they once did. And, conversely, overseas residents now hold many more Australian assets than they once did.

So, how do we explain this increase in the value of our residential land over recent decades?

So, how do we explain this increase in the value of our residential land over recent decades?

There are two main structural factors.

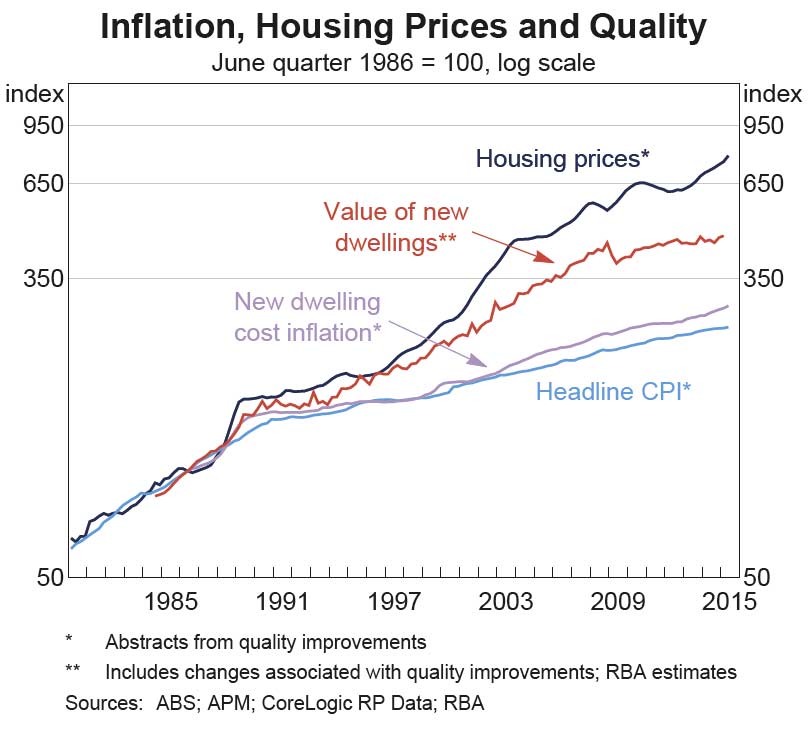

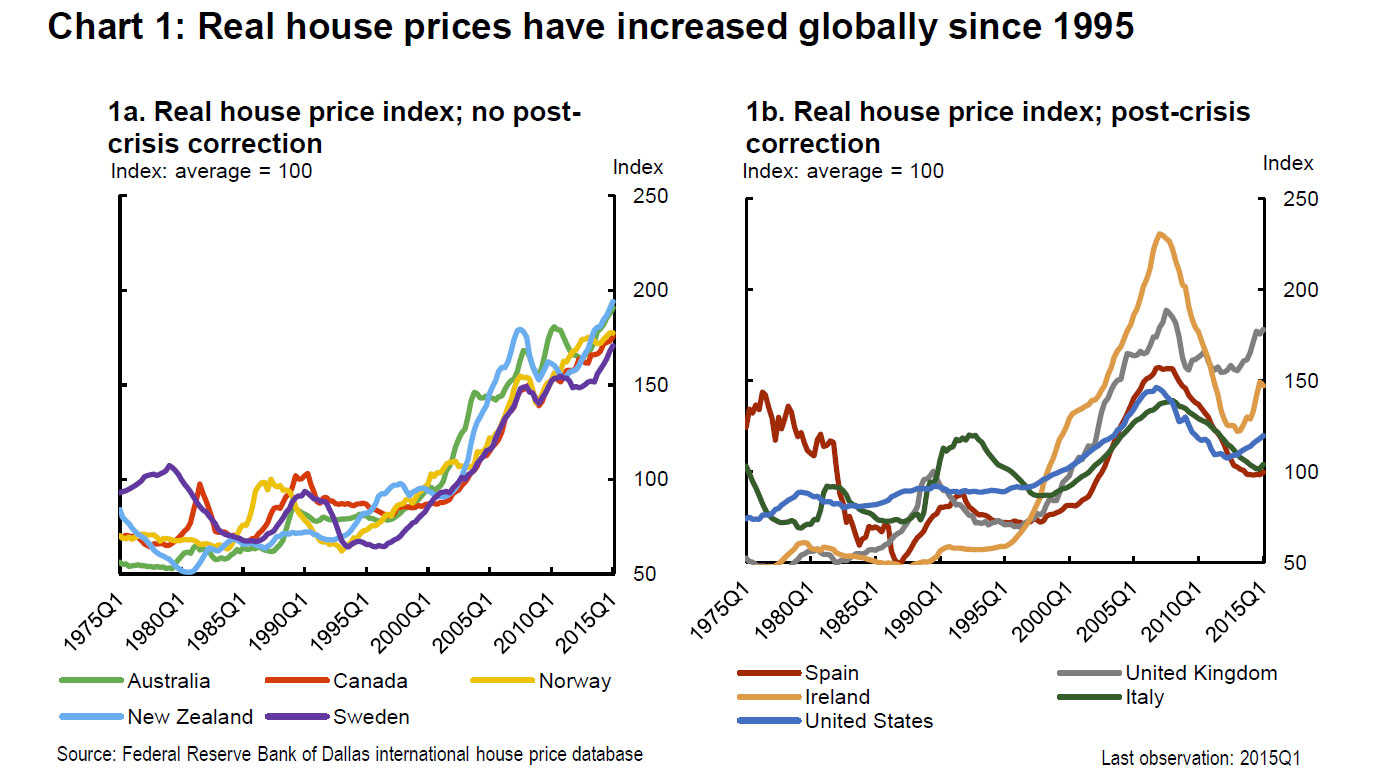

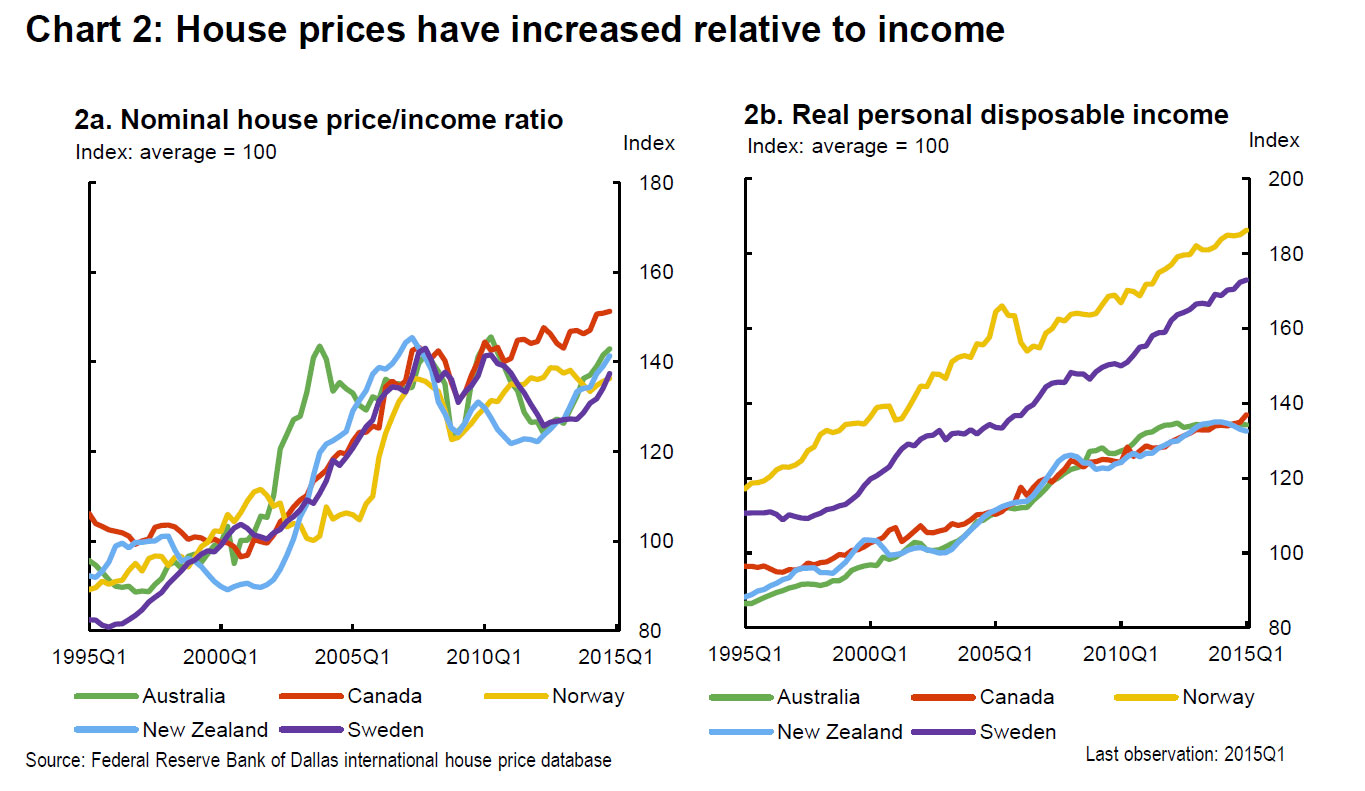

The first is the combination of financial liberalisation and low inflation. In the 1970s and 1980s, regulation of the financial system and high inflation served to hold down land prices artificially. They did this by limiting the amount that people could borrow. When the financial system was liberalised and low inflation became the norm, people’s borrowing capacity increased. Many Australians took advantage of this and borrowed more in an effort to buy a better property than they previously could have done. But, of course, collectively we can’t all move to better properties. And so the main effect of increased borrowing capacity was to push up housing prices, and that means land prices.

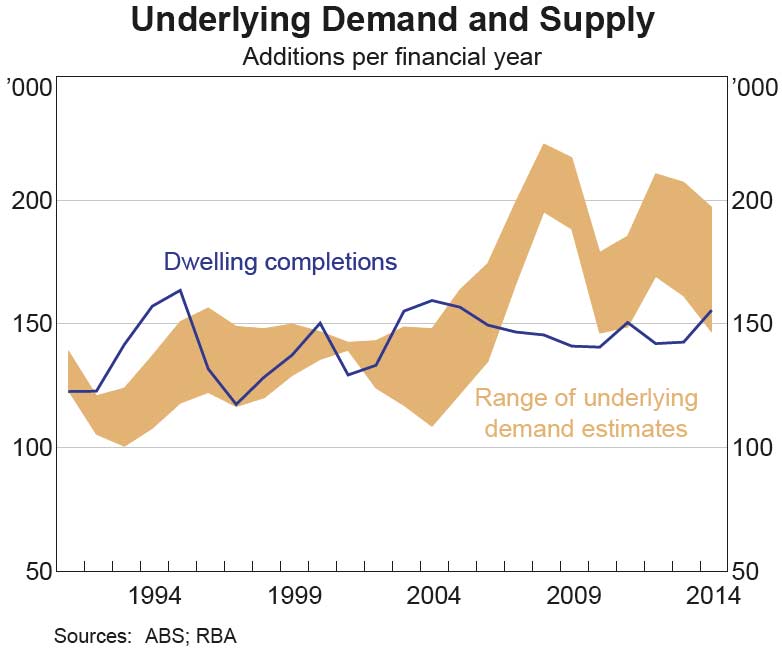

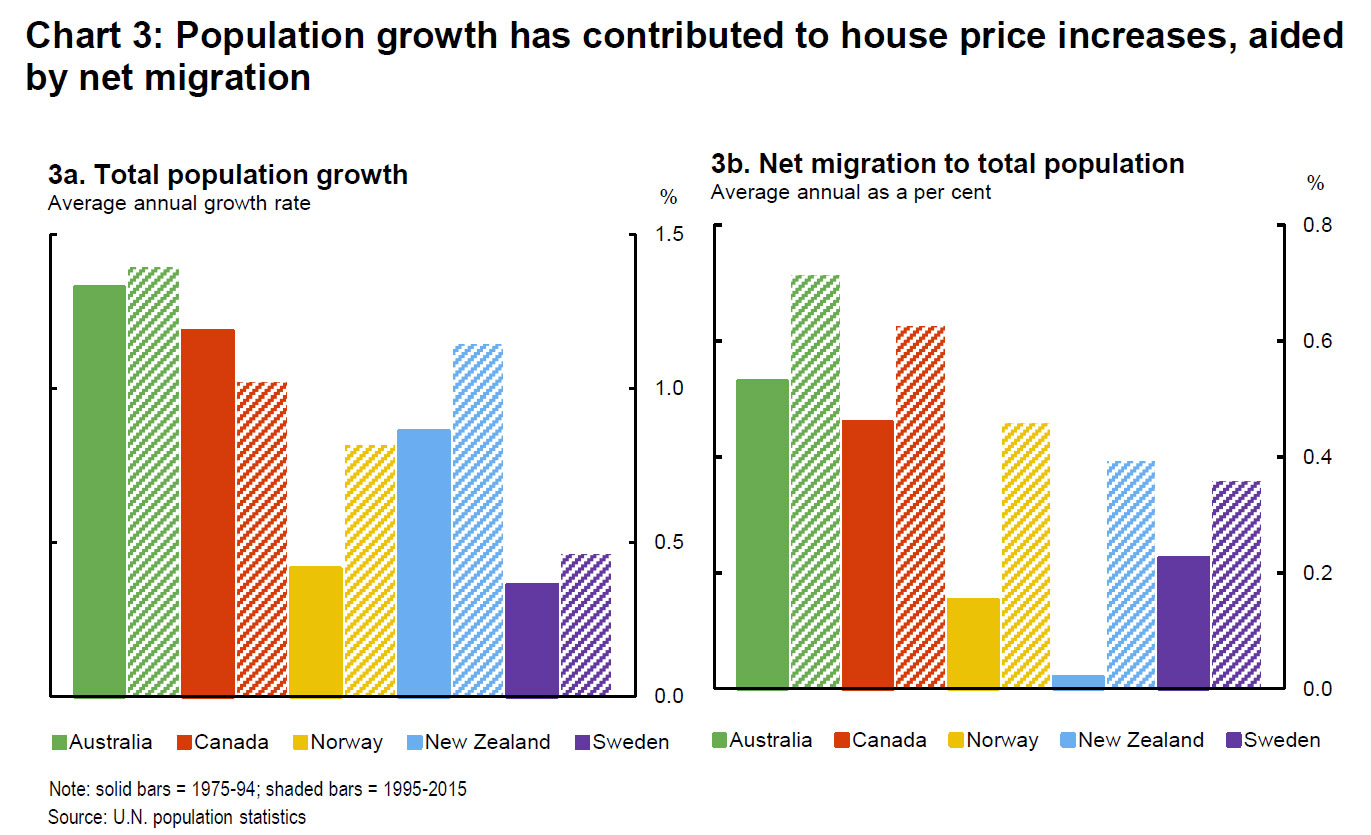

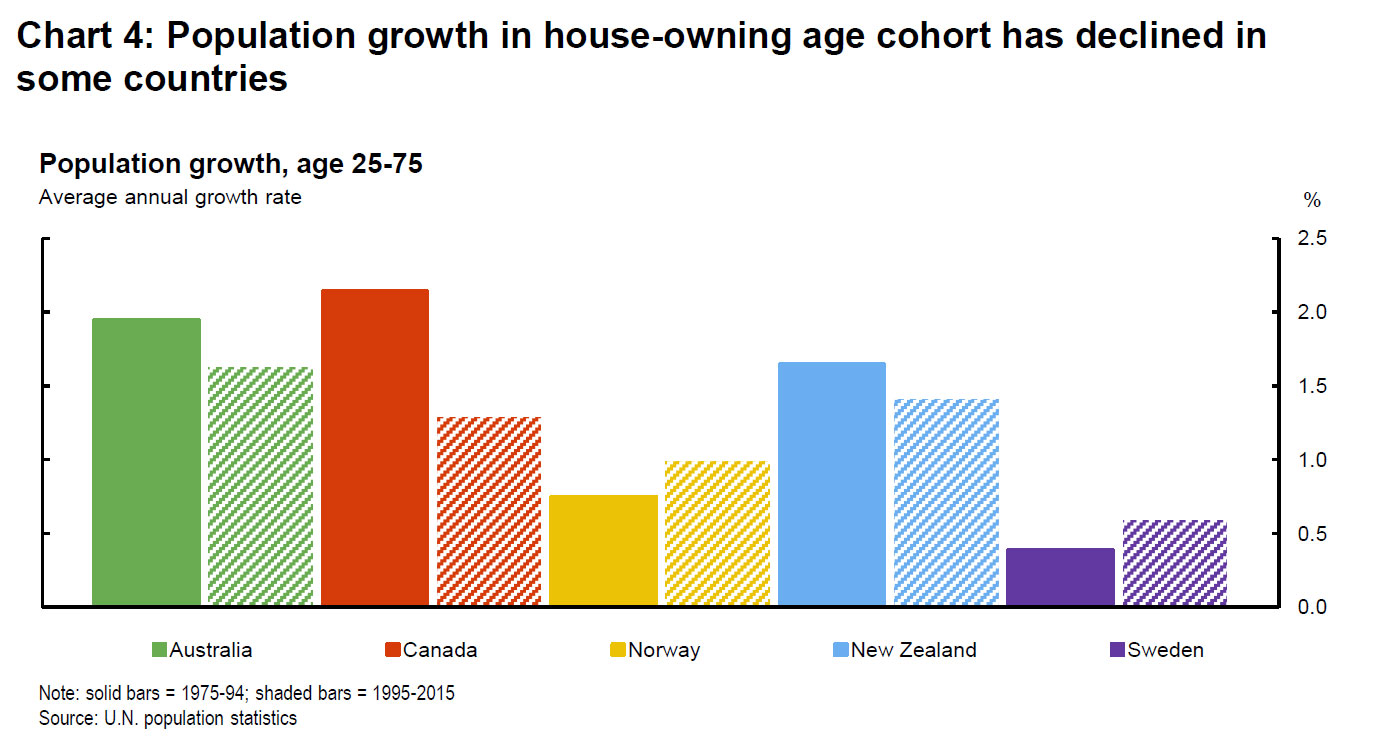

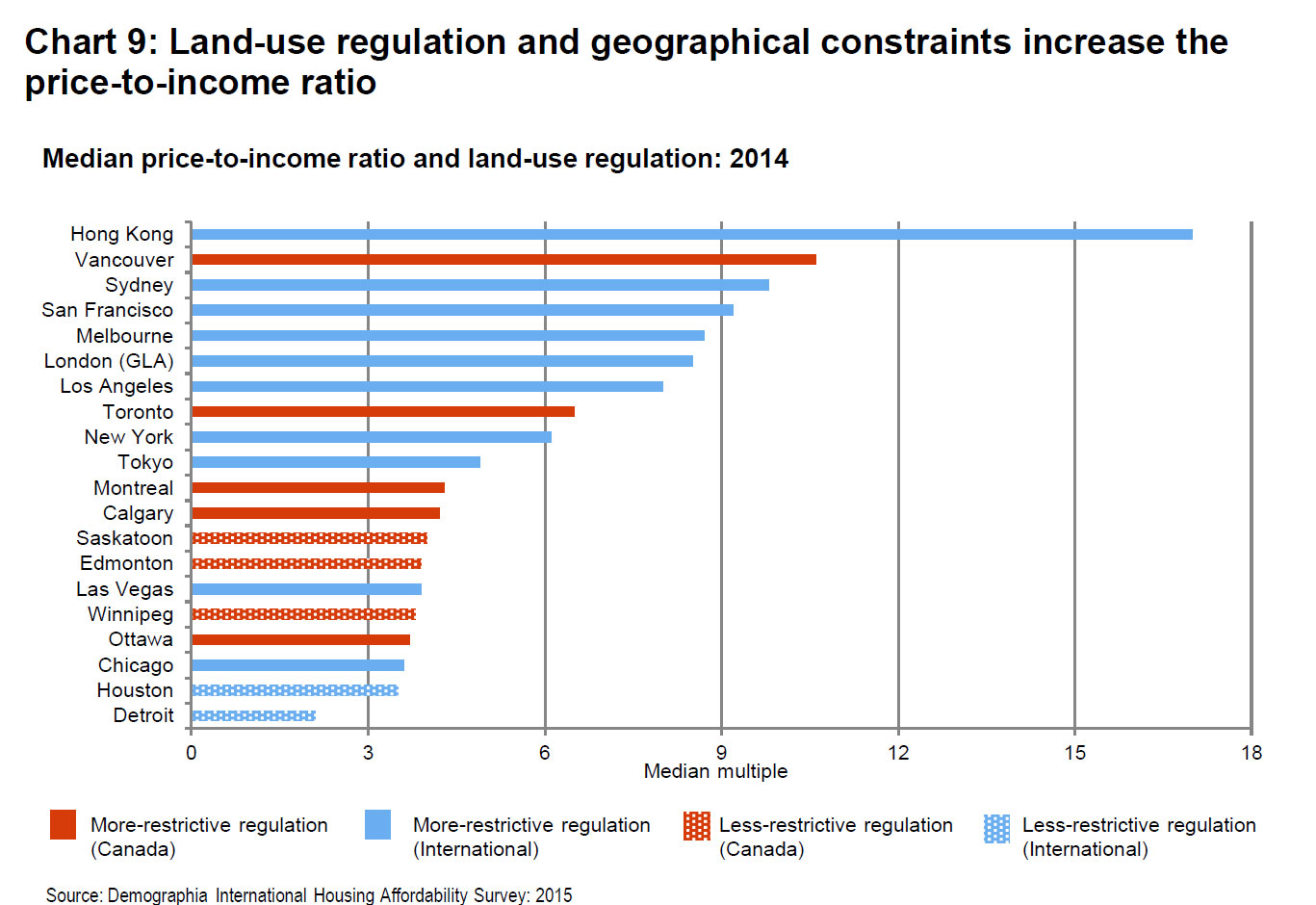

The second factor is the combination of strong population growth and the structural difficulties of increasing the effective supply of residential land. Since 1989, the Australian population has increased by more than 40 per cent, or around 7 million people, one of the fastest rates of increase among the advanced economies. The difficulties of responding to this on the supply side of the housing market have been well documented. They include the challenges of developing land on the urban fringe and of rezoning land close to city centres for urban infill. They also include, in some areas, underinvestment in transportation infrastructure. This underinvestment has effectively constrained the growth in the supply of ‘well-located’ land at a time when demand for this type of land has grown very strongly. The result has been a higher average price of land in our major cities.

Another possible structural explanation is that the higher land prices reflect an upward revision to people’s expectations of future income growth and thus the amount they are prepared to pay for housing services. One possible reason for this is that the growth of our cities generates a positive externality – by bringing more people together competition is improved and productivity is higher. While this might be part of the story, I think it is unlikely to be a central part. Real income growth per capita did pick up markedly from around the mid 1990s, but it has subsequently slowed substantially, with apparently little effect on the price of land relative to income.

So the story is really one of increased borrowing capacity, strong population growth and a slow supply response.

It is arguable that the main impact of higher land prices is not really to increase our national wealth, but to change the distribution of that wealth.

The distributional effects are in two dimensions. The first is cross-sectional, with the existing owners of dwellings receiving capital gains when land prices increase. The second is the distribution of wealth across generations, with the current owners of dwellings earning capital gains but future generations paying higher housing costs. Both of these aspects of changing wealth distribution have economic and social consequences, neither of which, I suspect, are yet fully understood.

How the intergenerational distribution ultimately plays out will depend critically upon the extent to which the gains that have accrued to the current generation are passed on to the next generation. In general, we know relatively little about intergenerational transfers, but what we do know suggests that things may be changing gradually. One illustration of this can be seen in the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, which suggests that, over time, there has been some increase in the share of first-home buyers that are receiving loans from family and friends. There is also some evidence of younger generations receiving increased assistance with household expenses from older generations, including by continuing to live in the family home.

Three issues relevant to monetary policy that are closely related to the issues I have been talking about.

Three issues relevant to monetary policy that are closely related to the issues I have been talking about.

Higher land prices and spending

The first of these is the link between higher housing prices and household spending.

There is a well-established research literature empirically demonstrating that higher housing wealth boosts household consumption. For example, work done by my colleagues at the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) has estimated that a rise in wealth of $100 leads to a rise in non-housing spending of between $2 and $4 per year.

There are two commonly accepted channels that explain this relationship.

The first is a pure wealth channel. To the extent that higher dwelling prices are perceived to increase wealth, households should spend a little of that extra wealth each year over their lifetime.

The second is the collateral channel, as higher land prices increase the value of collateral that can be posted by potential borrowers. The increased collateral makes it easier for credit-constrained households to borrow to increase their spending. Similarly, businesses can find it easier to finance projects that previously might have struggled to get finance.

Over recent years, there has, however, been some reinterpretation of the role of the pure wealth channel.

In part, this reflects the issues that I was speaking about a few moments ago; that is, that higher housing prices not only deliver capital gains to the existing owners but also imply a higher price of future housing services. The reinterpretation of the evidence is that the link between housing wealth and spending arises not so much through the traditional pure wealth channel, but rather because higher housing prices are sometimes a proxy for faster expected income growth into the future. And it is this lift in expected income growth that spending is really responding to.

Interestingly, other colleagues at the RBA have recently been examining this idea, again using household level data from the HILDA Survey. They find clear evidence in favour of a collateral channel, especially for younger households who are more likely to be credit constrained. In contrast, they find no evidence in favour of the traditional pure wealth effect. Instead, their evidence is consistent with the alternative expected-income idea. Perhaps, the most intriguing aspect of their results is that when housing prices in a particular area increase, renters in that area increase their consumption. The increase is not as large as for owner occupiers, but it is an increase. The conclusion that my colleagues reach is that it is a common third factor such as higher expected future income, or less income uncertainty, that is, at least partly, responsible for the observed association between housing wealth and spending.

If this conclusion is correct, then I think it helps partly explain what is going on in the economy at the moment. In the early 2000s, when housing prices and real incomes were rising quickly, many households used the higher value of their housing assets to increase their spending. Nowadays, this is not happening on the same scale that it once was. With slower expected future income growth and increased concerns about future housing costs, the response to higher housing prices looks to be smaller than it was previously. And this smaller response is affecting overall spending in the economy.

Liabilities and risk

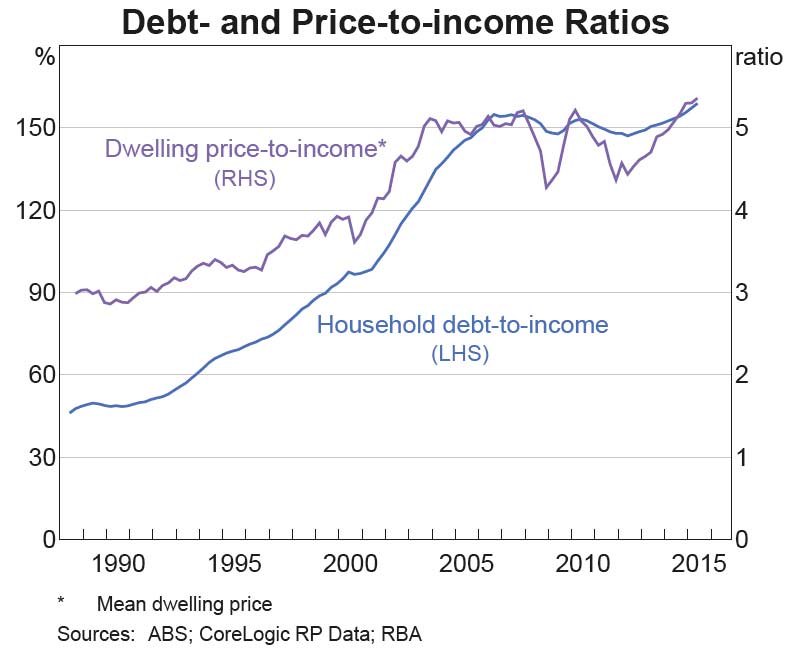

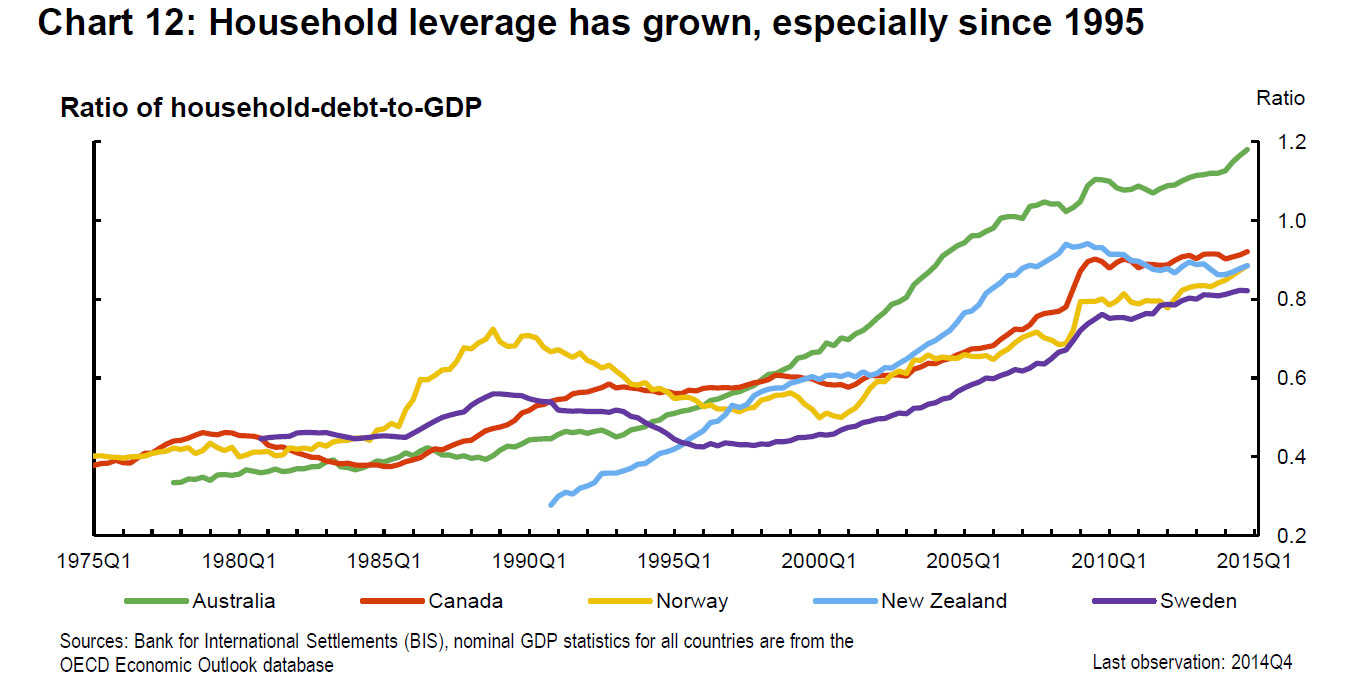

The second issue that I wanted to touch on is the increase in debt that has accompanied the increase in land prices.

Throughout this talk I have barely touched on the liability side of the balance sheet. This is largely for the reason that I spoke about at the start, namely that financing transactions that are internal to the country do not change Australia’s net wealth. However, these transactions can have a material impact on the profile and riskiness of the individual balance sheets within the economy.

The rise in land prices that I have spoken about is inextricably linked to the rise in household borrowing. Together, these two developments have grossed up the household sector’s balance sheet. This means that, on the assets side of the balance sheet, a given percentage change in housing prices has a bigger effect than it once did. And on the liabilities side, movements in interest rates also have a bigger effect.

We are still trying to understand fully the implications of all of this. However, I think it is difficult to escape the conclusion that household balance sheets are, on average, a little more risky than they once were. Many Australian households also seem to have reached a similar conclusion. This is reflected in the decision by many Australians to take a more prudent approach to their spending over recent years.

We are still trying to understand fully the implications of all of this. However, I think it is difficult to escape the conclusion that household balance sheets are, on average, a little more risky than they once were. Many Australian households also seem to have reached a similar conclusion. This is reflected in the decision by many Australians to take a more prudent approach to their spending over recent years.

I suspect that it is unlikely to be in our national interest for this more prudent approach to give way to household consumption once again growing consistently much faster than our incomes. This is something we continue to be cognisant of in the setting of monetary policy. Some decline in the rate of household saving is probably appropriate as the economy rebalances after the terms of trade and mining investment booms. But, given the position of household balance sheets, it is unlikely to be in our long-term interest for a consumption boom to be financed by a pick-up in household borrowing.

Generating growth

That brings me to my final issue: that is the need to generate sustainable growth in the economy.

Monetary policy can play some role here, including by helping reduce uncertainty by maintaining low and stable inflation and overall stability in the economy. But monetary policy is, ultimately, not a driver of medium-term economic growth. Indeed, while low interest rates are currently helping the economy through a period of transition, an extended period of low interest rates implies ongoing low returns to savers and low underlying returns on assets. This is not a world to which we should aspire.

One of the challenges we face as a country is to lift the expected risk-adjusted return on investment in new assets, whether they be physical assets or human capital. If we can do this, then we will see the investment in new assets that is crucial to the sustainable expansion in the economy.

There is no single lever that can be pulled here. But neither is there a shortage of sensible ideas that, if implemented, could improve the environment for the creation of new assets in Australia.

These ideas include: a strengthening of the culture of innovation; the removal of unnecessary and overly complicated regulation; and making competition work effectively in markets across the country. Increased investment in infrastructure, including in transport, probably also has a role to play here. Done properly, it could help lift the return to other forms of investment in a wide range of industries across the economy. Better transportation can also increase the effective supply of well-located land, making housing more affordable for many Australians. None of this is easy, but neither is it impossible.