In my latest discussion with Veronica Morgan in the “Elephant In The Room” podcast, we look at household perceptions and financial data across our surveys.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

In my latest discussion with Veronica Morgan in the “Elephant In The Room” podcast, we look at household perceptions and financial data across our surveys.

I caught up with journalist Royce Kurmelovs, author of “Just Money”, a newly published book which examines how Australians became some of the most indebted people in the world.

Fair disclosure, I was interviewed by Royce as he researched the subject.

Economist John Adams and Analyst Martin North examines the latest data, and considers the implications.

The earlier show with Eddie Hobbs we discussed:

Steve Mickenbecker from Canstar and I discuss the complexity of health insurance

The latest edition of our finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

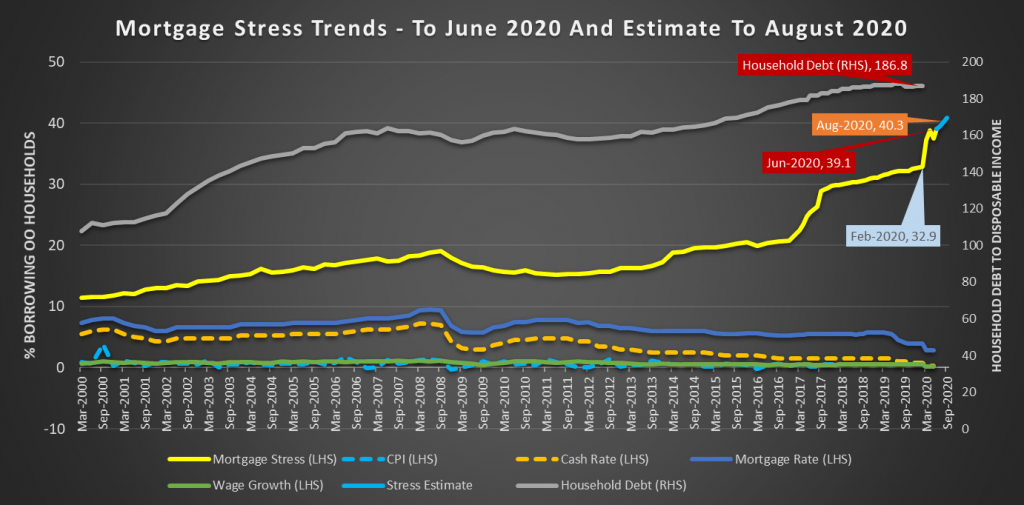

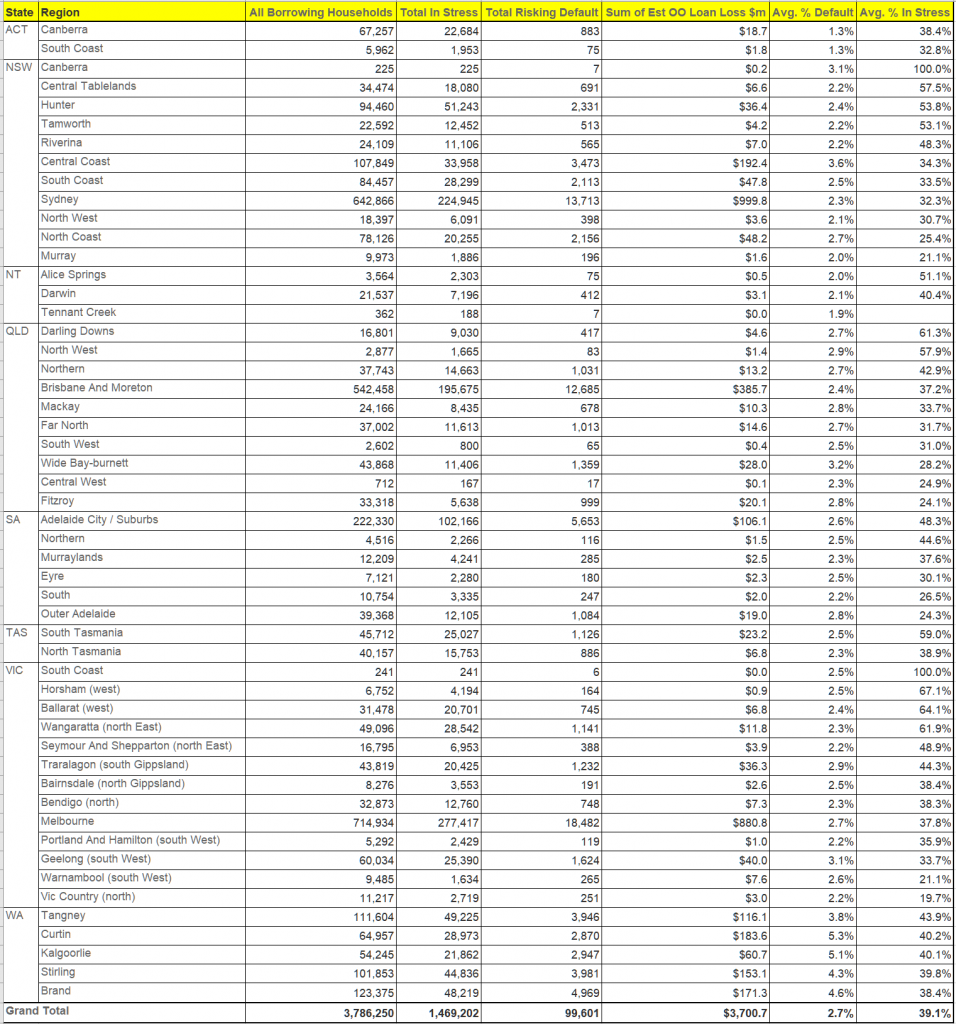

Digital Finance Analytics has released the results of our rolling 52,000 household surveys to the end of June, which reveals that mortgage stress rose to 39.1%, compared with 37.5% in May. In addition, rental stress was 39.4%. Moreover, a larger number of property investors with a mortgage (51.3%) are underwater from a cash-flow perspective. This is new analysis which suggests investors are caught in the financial crisis headlights.

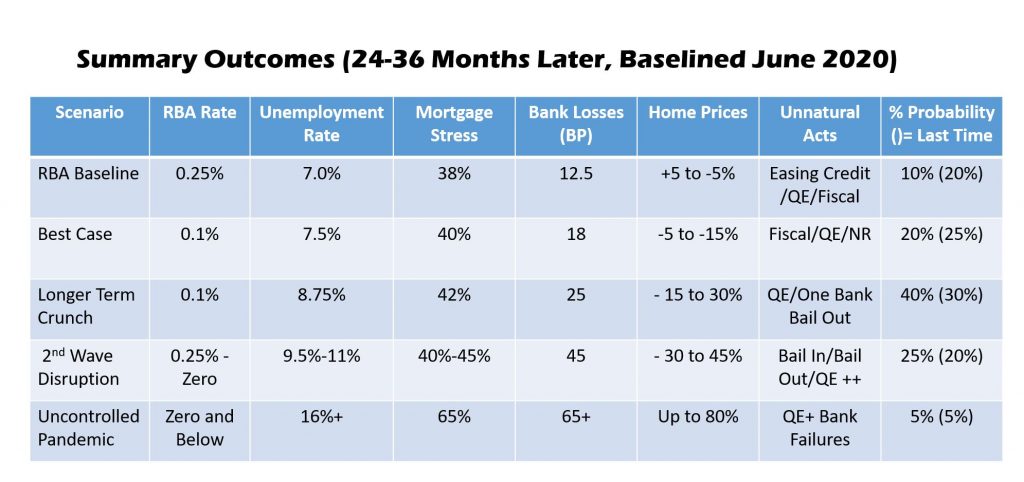

We discussed all this on our live stream last night, where we also updated our price scenarios:

We measure stress in cash-flow terms, money in, money out, rather than a set percentage of income dedicated to paying mortgage or rental payments. If the net income flows are lower than the net payment outflows, households are classified as stressed. These households will cut back on expenditure, put more of credit cards, or tap into deposits. While, they may have access to other assets – for example investment properties or share portfolios, negative cash flow remains a significant challenge.

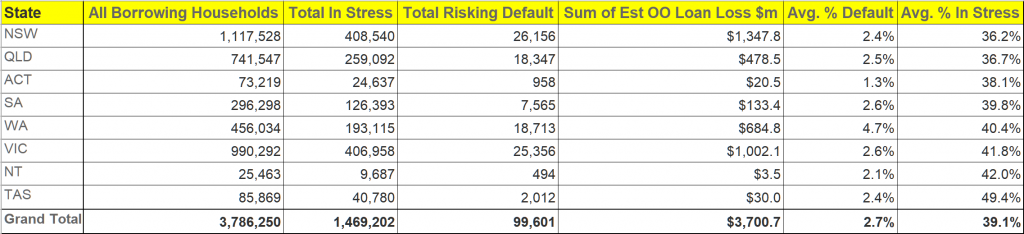

This equates to 1.47 million owner occupied mortgage holders under financial pressure, and 1.7 million households in rental accommodation. More than 820,000 property investors are in difficulty.

The complex interplay of higher unemployment, JobSeeker and JobKeeper, together with the 490,000 mortgages with payment deferrals provides the backcloth for our analysis. However, by examining the financial flow status of households we have noted some realignment of households in the past month, with more casual and part-time workers able to return to work, but a significant rise in structural unemployment as larger companies, such as larger retailers, big consulting firms, and finance firms, make reductions in staff. These permanent cuts reflect the rightsizing of businesses in reaction to the economic downturn. Then we have the new Melbourne lock-down.

Turning to the detailed analysis, across the states, Tasmania has the highest proportion of households in mortgage stress, at 49.4%, followed by the NT and Victoria. However, the largest counts of stressed mortgage holders are in NSW, with 408,540 and VIC with 406,958. The highest risk of default rates are found in WA at 4.7%, VIC at 2.6% and SA at 2.6%.

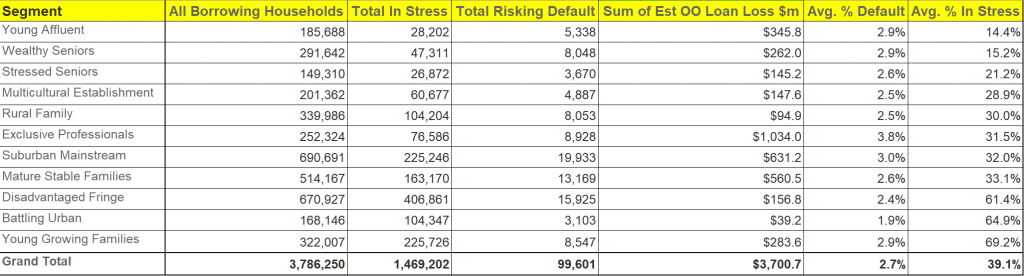

Within our household segments, the highest mortgage stress levels are among Young Growing Families, at 69.2% of households, which includes cohorts of recent first-time buyers, with more than 225,000 households at risk. Next, those on the urban fringe, are also exposed, along with more typical battlers. We are also seeing a rise in affluent stress, where households on higher incomes are experiencing significant issues. The Exclusive Professional segment, the top few percent on an income basis, include 31.5% stressed, which equates to more than 76,000 households across the country. Significantly, in value terms, they hold around 28% of all default risk to the banks by value.

Mortgage stress is apparent not just in the main urban centres, but across the regions. This is a structural not caused by COIVD, but amplified by it.

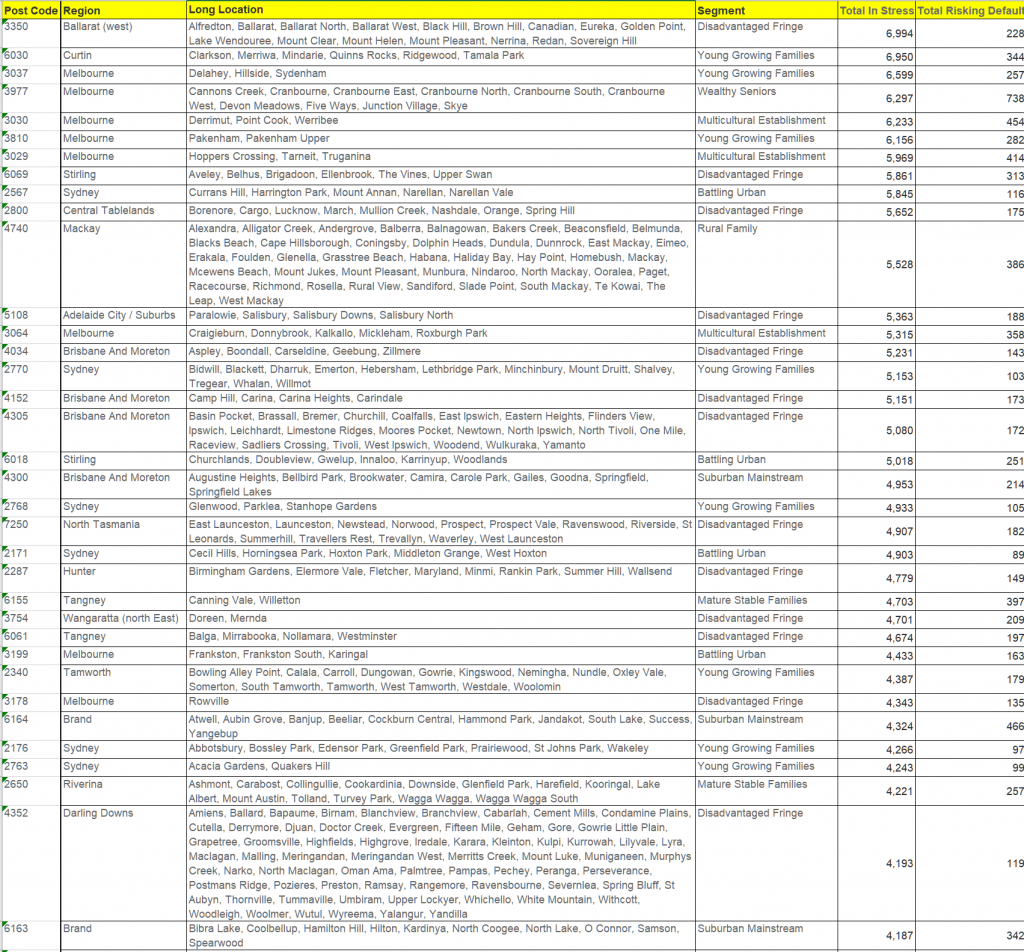

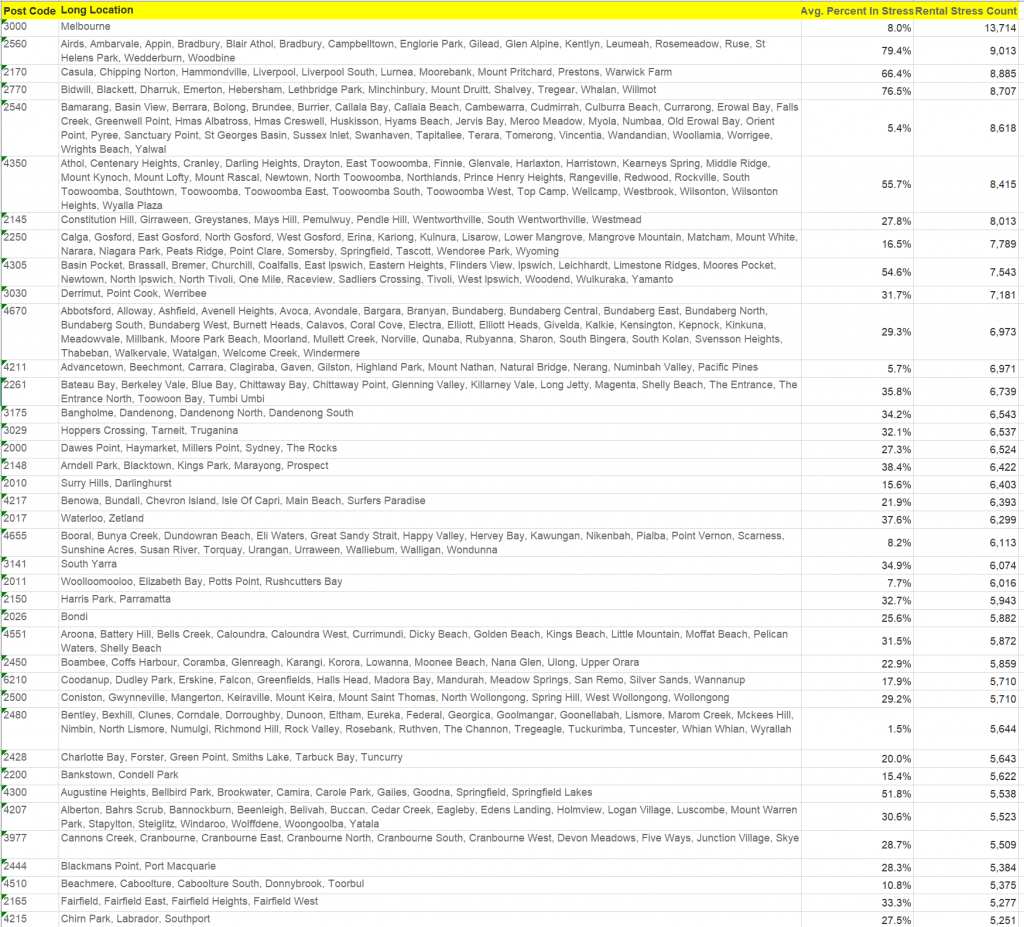

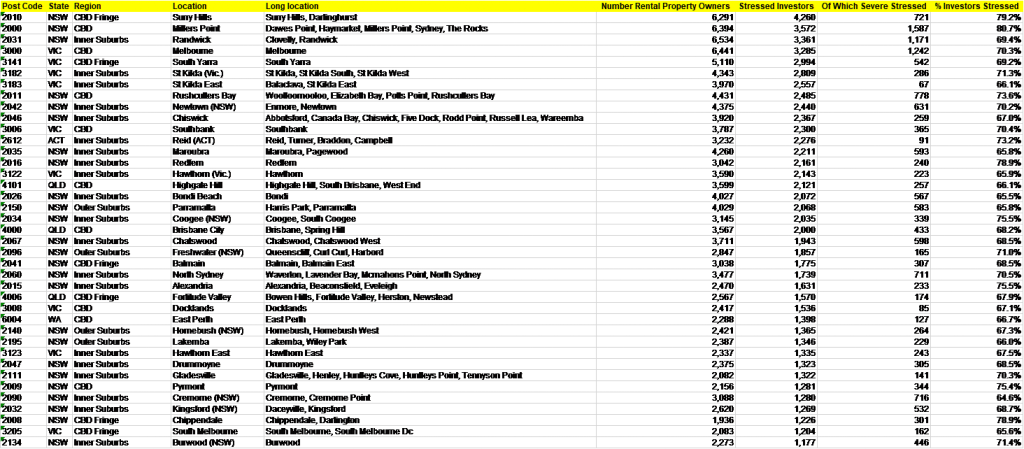

Stress varies by post code. Here are the top 30:

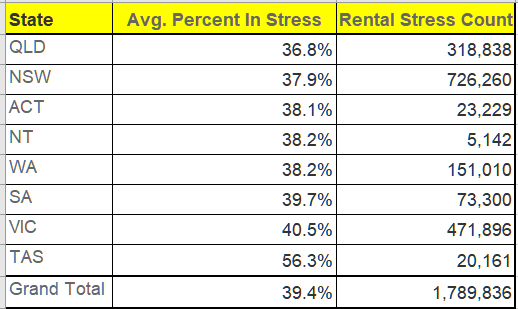

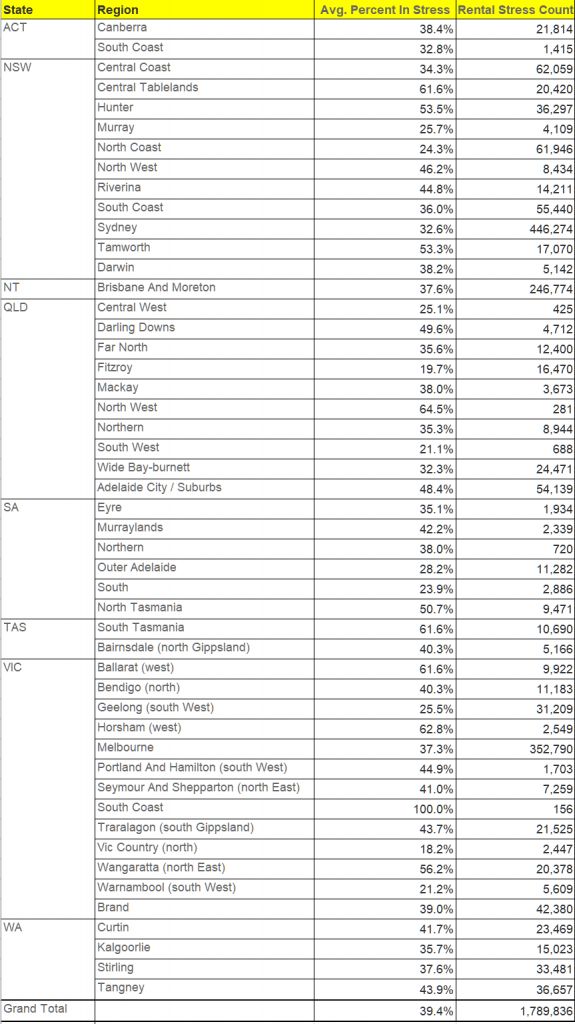

Turning to rental stress, the patterns are somewhat similar. The highest stress among renters is found in TAS at 6.3%, followed by VIC at 40.5% and SA at 39.7%. Whilst on a percentage basis the lowest levels of stress are in QLD (36.8%) and NSW, 37.9%, in fact the largest count of stressed households in also in NSW, as here the proportion of households renting is the highest (reflecting the poor affordability of housing in the state, despite rents falling in real terms.

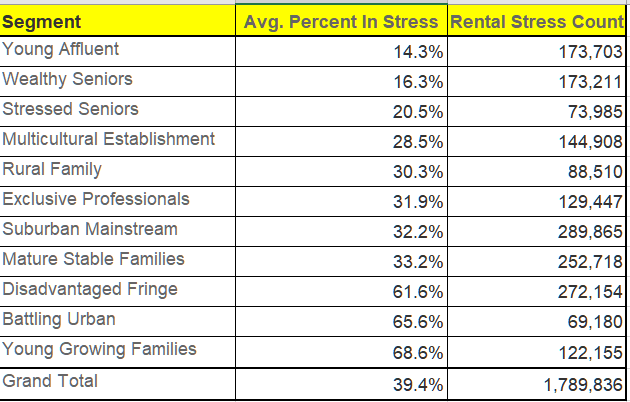

Across the DFA household segments, once again, Young Growing Families are most stressed, at 68.6%, whereas the largest counts are among suburban mainstream households (289,000), Disadvantaged Fringe (272,000) and Mature Stable (252,000).

Once again rental stress is widely distributed across the regions, and should not be regarded as a capital city problem.

Rental stress by postcode

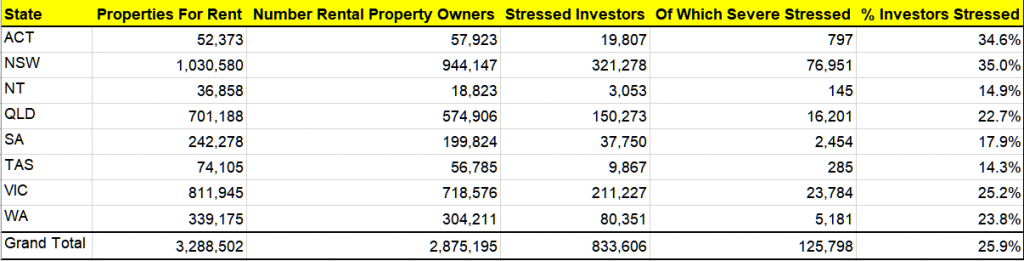

Finally, for the first time we are also reporting on property investors, and their property holdings. Across Australia, there are around 3.2 million properties available for letting (including short-term AirBnB type rentals as well as longer term residential). This excludes motels and hotel accommodation.

These properties are owned by around 2.8 million entities, including households and businesses. Around half the property available is covered by investment mortgages, which equates to around 1.65 million borrowers.

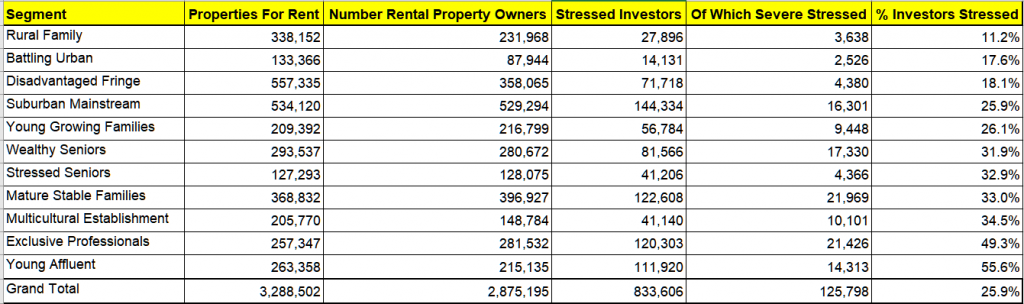

Of these 2.8 million entities, around 830,000 on a cash-flow basis, are not making sufficient to recover the costs of owning and letting their properties (stressed investors) of which 126,000 are severely stressed, most often because of low occupancy, or high repair costs. This is around 25.9% of all investment property, and 51.3% of mortgaged properties.

One complexity when analysing the more detailed footprint of investment property is that many owners live in different post codes to the properties they own. To account for this, we report the number of properties based on the location of the property itself, while the number of property investors and their stress status are reported on the basis of their home address, not the address of the property. That said, more than half reside in the same post code as their investment property.

NSW has the highest proportion of stressed investors at 35%, or around 321,000.

By segment, the most highly stressed investors are Young Affluent and Exclusive Professional investors (many of whom have multiple investment properties, so the pain is magnified).

The top stressed investor postcodes include areas close the CBD of Sydney and Melbourne, including Surry Hills, Millers Point and Randwick in Sydney and Melbourne CBD, South Yarra and St Kilda in Melbourne.

The full stress series is available via our Patreon page for US$50 plus GST. You can subscribe there to receive full monthly updates.

Are you on the right credit card? If not you are probably paying too much. I discuss this important issue with Canstar’s Steve Mickenbecker.

https://www.canstar.com.au/author/steve-mickenbecker/

Are you on the right credit card? If not you are probably paying too much. I discuss this important issue with Canstar’s Steve Mickenbecker.

I discuss mortgage rates with Canstar’s Steve Mickenbecker, and how its possible to save thousands of dollars over the life of a mortgage. We discuss the “apathy tax” and what we can do about it!

My latest discussion with Investment Manager Tony Locantro from Alto Capital. https://www.altocapital.com.au/

Things are getting interesting!