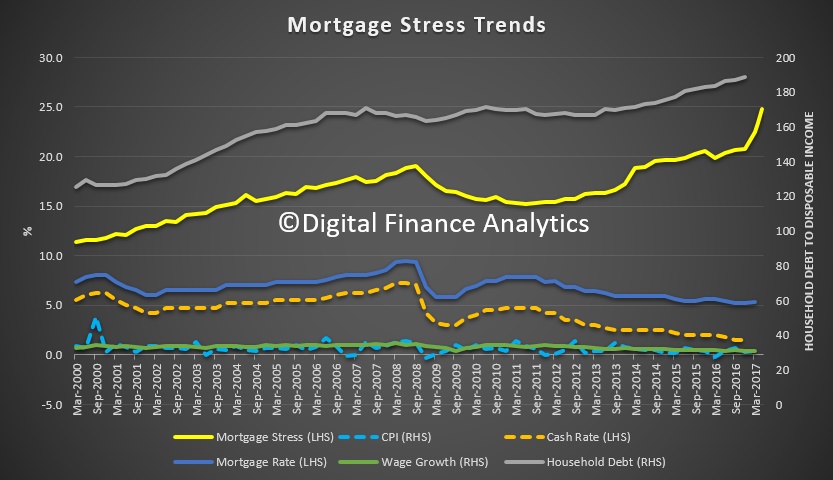

More people are now saying that households need to brace for mortgage rate rises. Among the crowd is Malcolm Turnbull who warned households to prepare for interest rates to climb.

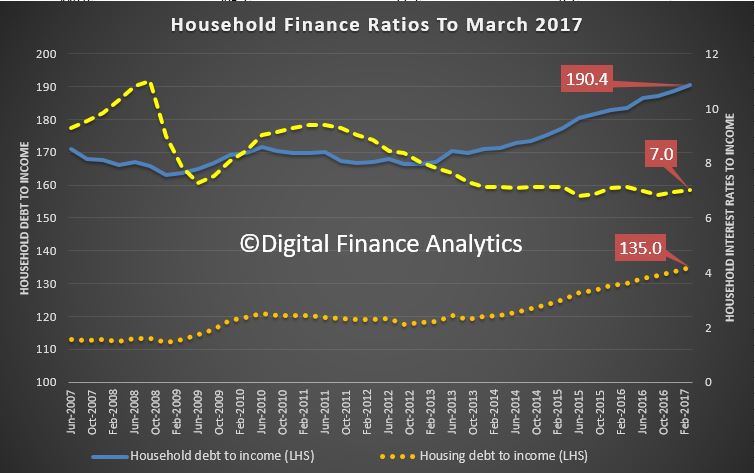

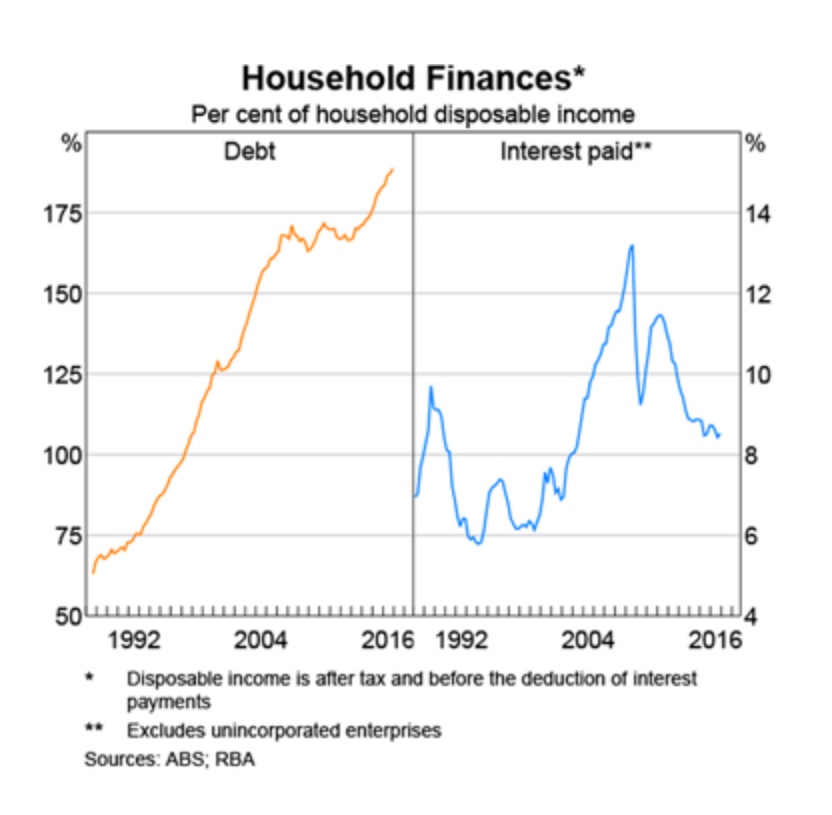

It is all a bit late given the level of debt which we have across Australia. As we discussed before, the debt quagmire will really hurt.

It is not that employment is too bad, but incomes are static, costs are rising, and underemployment is the spectre at the feast.

But lets be clear, it is not a financial stability problem, yet. It is highly unlikely the banks will see their mortgage defaults rise that much, because currently many households are still protected by lofty capital gains sufficient to repay the lender. They also have tremendous pricing power, as has been demonstrated in the past few months, with a litany of out of cycle rate hikes. Expect more to come. Their capital base is strong, and rising (and APRA has been light on them). As a result, banks profits will rise – this explains recent stock market moves.

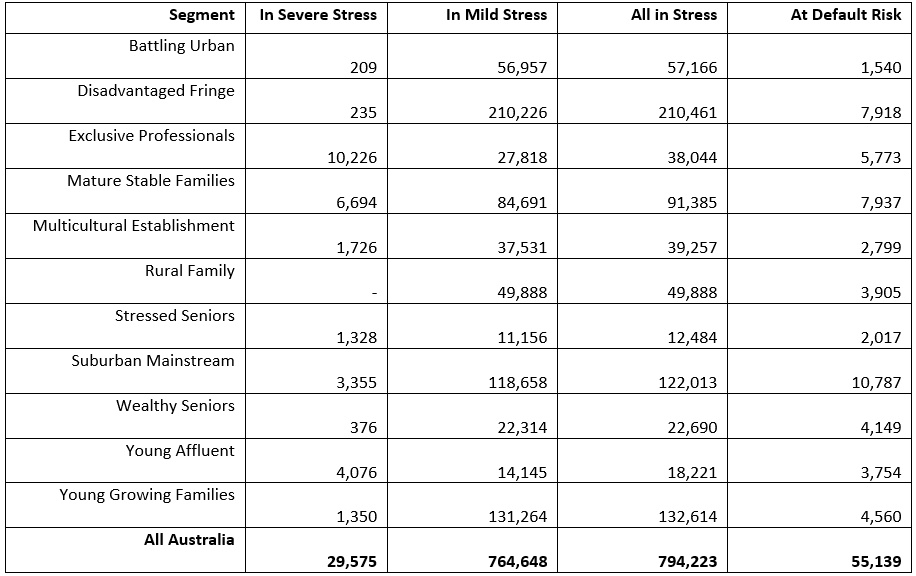

No, the real impact is among households. We think here are three groups of households who should be taking great care just now.

There are some amazing offers around for first time buyers, and lenders are falling over each other to try and attract them. This is because banks need new loans to fund their growth. But these buyers should beware. They are buying in at the top of the market, when rates are low. Banks have tightened their underwriting standards, but still they are too lax. Just because the bank says you can afford a loan does not mean it is the right thing to do. Any purchaser should run the numbers on a mortgage rate 3% (yes 3%) higher than the current rates on offer. If you can still afford the repayments, then go ahead. If not, and remember incomes are not growing very fast – best delay.

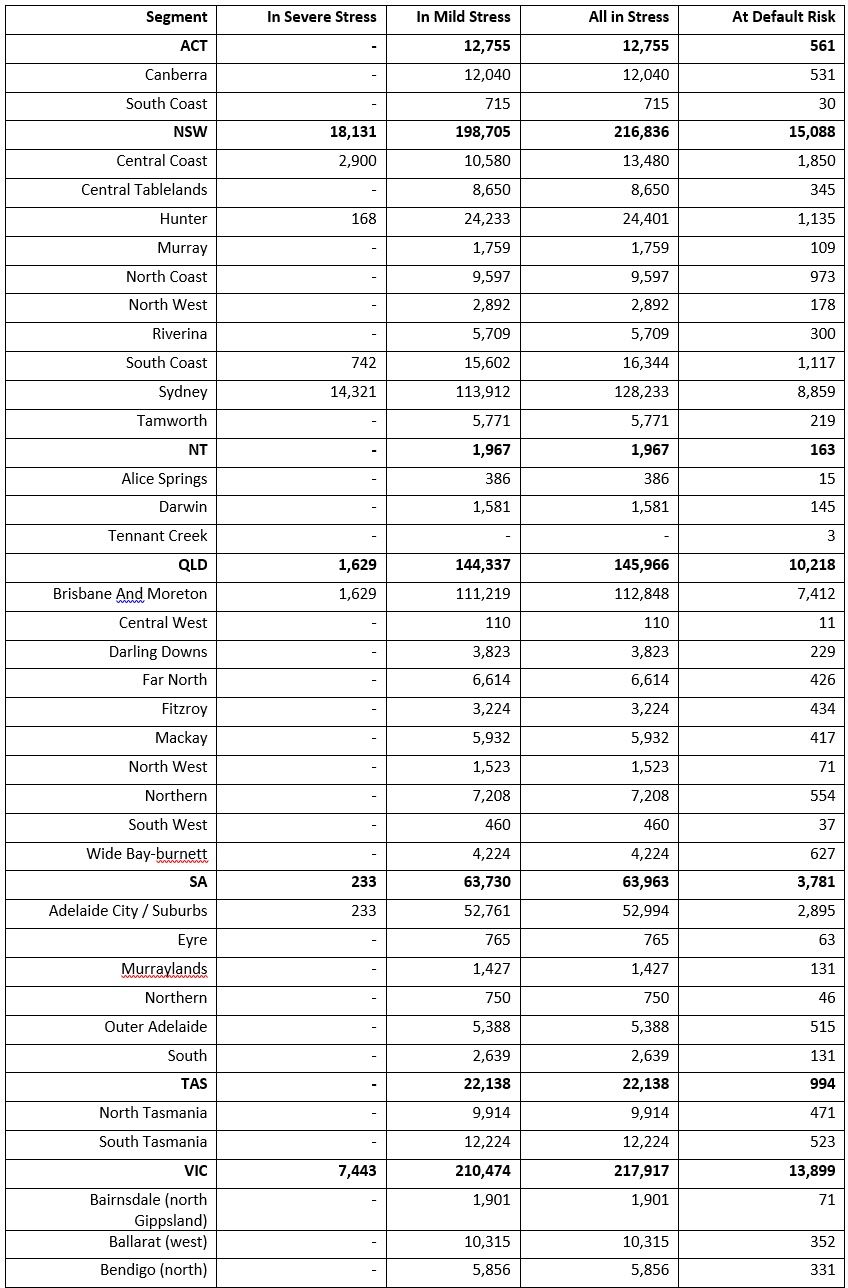

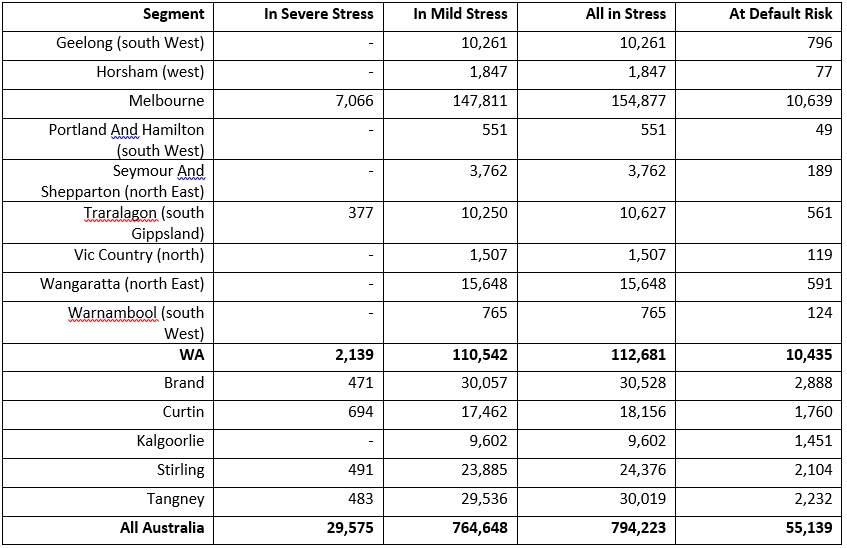

Second, there are people with mortgages in financial difficulty now. Well over 24% of households do not have sufficient cash-flow to pay the mortgage and other household expenses. The temptation is to use the credit card to fill the gap – but this is expensive, and only a short term fix. Households in strife need to build a budget (less than half have one) so they know what they are spending, and start to cut back. Talk to your lender also, as they have an obligation to assist in cases of hardship. And be very careful about refinancing your way out of trouble, it so often does not work.

Third there are property investors who are seeing rental incomes and mortgage repayments moving in opposite directions. As a result, despite tax breaks, the investment property looks a less good deal. Of course recent capital gains are there – and some savvy investors are selling down to lock in capital value – but be careful now. New property investors are in for a shock as mortgage rates rise further. And multiple investors, are most at risk. Should property values decline, then this will mark the real turning point; but we think the investment property party may be over.

This will play out over the next couple of years, but the bottom line is simply, mortgages will be more expensive, and households need to prepare now. Turnbull is right.