Despite all its huff and puff on housing, a senior economist has warned voters the government will disappoint on the one reform almost everyone wants.

Professor Richard Holden said it would be a “real shame but no surprise” if Tuesday’s federal budget failed to curb tax perks for property investors.

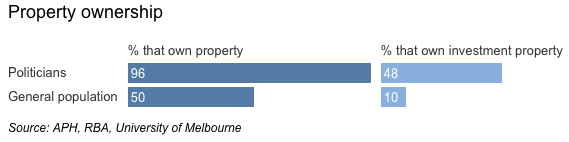

“There is now consensus that there should be a move away from negative gearing and to prune back the capital gains discount. I think everyone agrees except the government and maybe the Property Council,” he told The New Daily.

“It’s very hard to find anybody else. You’ve got Jeff Kennett, John Hewson, Malcolm Turnbull before he became Prime Minister. Everyone seems to agree it’s a bizarre system that’s driving up prices.”

What’s in the housing package? Click to find out

After haemorrhaging support to Labor by doing nothing to help first home buyers in his pre-election 2016 budget, Treasurer Scott Morrison spent the end of last year swearing he’d focus on housing affordability this time around.

He’s been forced to walk back some of that rhetoric, as policy options evaporated under pressure from Labor, interest groups and the Abbott faction.

What hasn’t changed is Mr Morrison’s pledge not to touch negative gearing. But he’s been less emphatic on the capital gains tax discount, which allows landlords to pay tax at their marginal rate on only 50 per cent of the capital gains they realise when they sell a property.

A wide array of experts, including Richard Holden, agree these tax perks favour wealthy investors, and contribute to the difficulty of young Australians entering the property market, at least in Sydney and Melbourne.

A new survey by CoreLogic, a property data firm, found that 87 per cent of non-home owners are concerned about affordability; 30 per cent are looking to inheritance or parents to help them buy; and 62 per cent living with parents say they can’t afford to move out. It surveyed 2010 people aged 18 to 64.

By CoreLogic’s estimate, houses cost 7.2 times the yearly income of an Australian household, up from 4.2 times income 15 years ago. And a 20 per cent deposit costs 1.5 years of household income, up from 0.8 years.

Professor Holden was more enthusiastic about incentives for older Australians to downsize to smaller homes, especially if that involves a stamp duty discount.

“Stamp duty is like the worst tax in the history of the world and everyone with a minute’s economic education thinks it should be replaced with a land tax, so anything that pushes in that direction is a good idea.”

However, if the incentive allowed wealthy individuals to exceed the superannuation balance cap, that “would be a concern, depending on how it’s structured”.

Professor Holden also praised the government’s push to invest more in affordable rental housing: “The idea that housing affordability bites at the very lowest end is a really big deal.”

But he rubbished the government’s proposal to offer subsidised savings account to help first home buyers save a mortgage deposit.

“We saw the government float the idea of accessing super. Now, myself and Saul Eslake and others all came out vociferously and angrily against that. I don’t know if it was causal, but they backed down,” Professor Holden said.

“But now they’re talking about tax-preferred savings accounts for first home buyers, and for the life of me I can’t understand why they can’t seem to get through their heads that anything of that nature is just boosting demand.”

Daniel Cohen, co-founder of lobby group First Home Buyers Australia, said he disagreed with the view that subsidised savings accounts would only push up prices.

“As a standalone policy, they are correct, which is why we want to see policies that are also decreasing demand from investors, and we want to see affordable supply also increase,” Mr Cohen told The New Daily.

“What economists are not considering, I feel, is that first home buyers still have a deposit hurdle, and with the current costs of living, average wages and stamp duty, that is a really big hurdle.”

He said the accounts would act as “financial literacy” to encourage young Australians who might not have considered it to save for a home.

For Mr Cohen, the biggest budget disappointment would be no reform on negative gearing and capital gains.