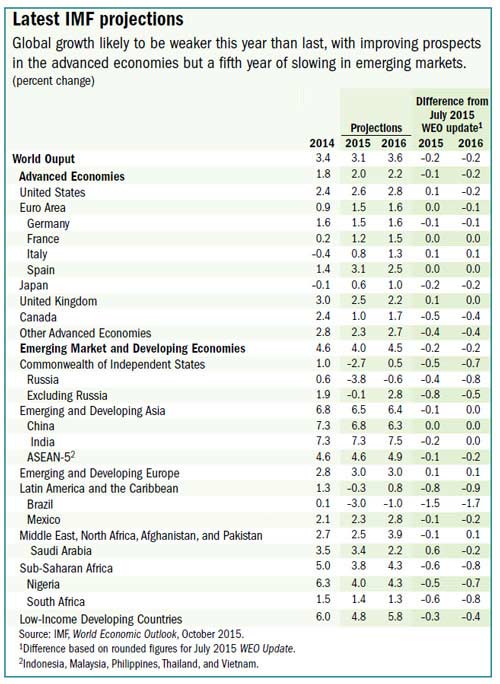

In the latest release, the IMF have provided data to October 2015, and also some specific analysis of the Australian housing market. We think they are overoptimistic about the local scene, and we explain why.

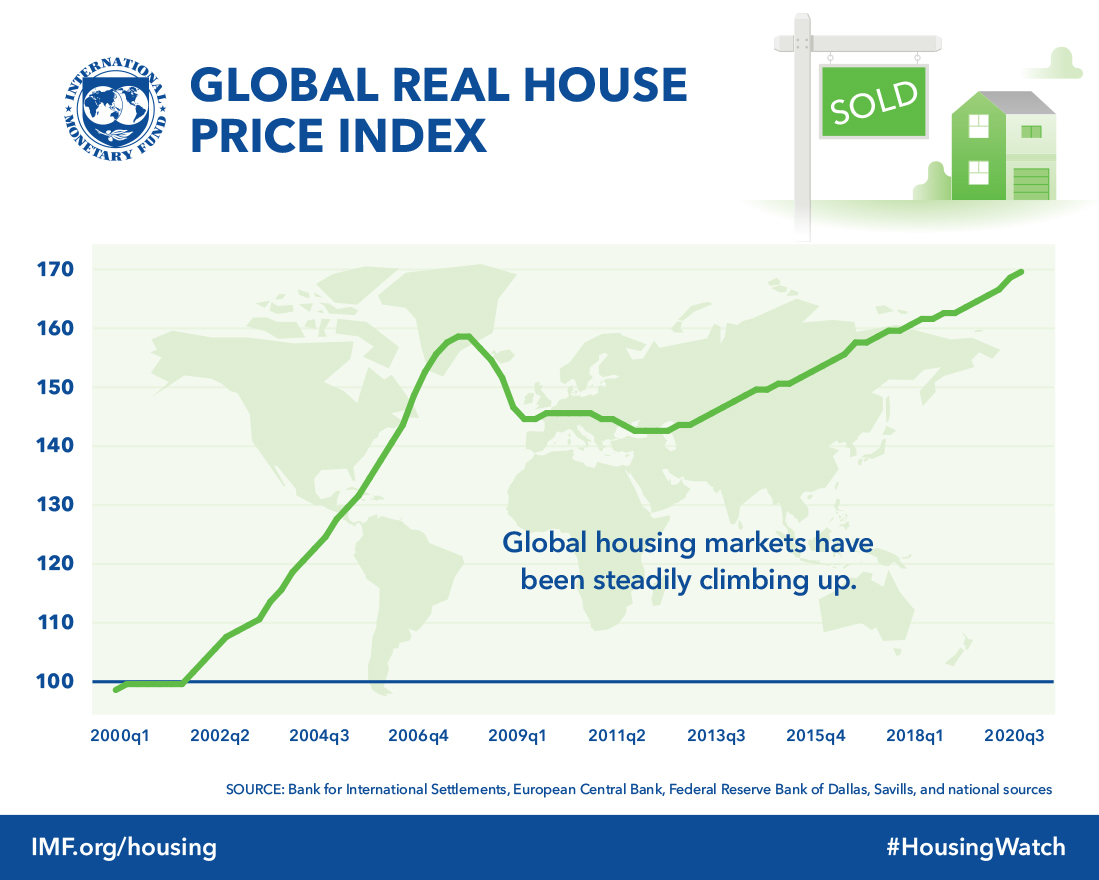

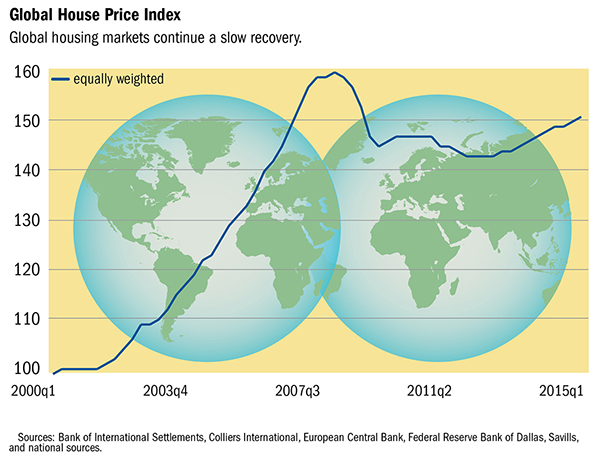

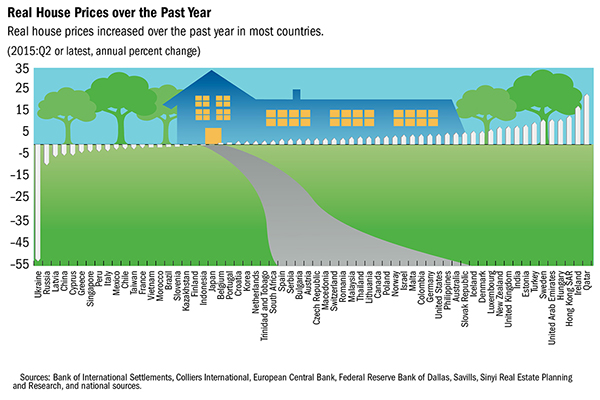

But first, according to the IMF, globally, house prices continue a slow recovery. The Global House Price Index, an equally weighted average of real house prices in nearly 60 countries, inched up slowly during the past two years but has not yet returned to pre-crisis levels.

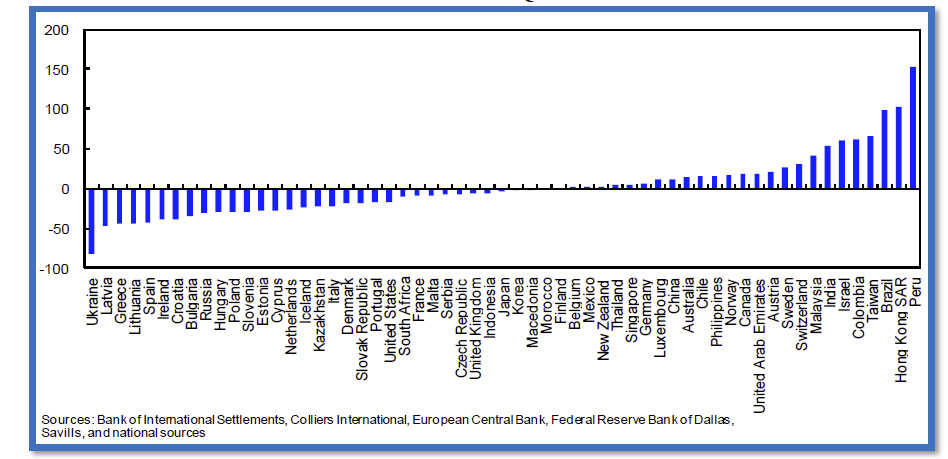

As noted in previous quarterly reports, the overall index conceals divergent patterns: over the past year, house prices rose in two-thirds of the countries included in the index and fell in the other one-third.

As noted in previous quarterly reports, the overall index conceals divergent patterns: over the past year, house prices rose in two-thirds of the countries included in the index and fell in the other one-third.

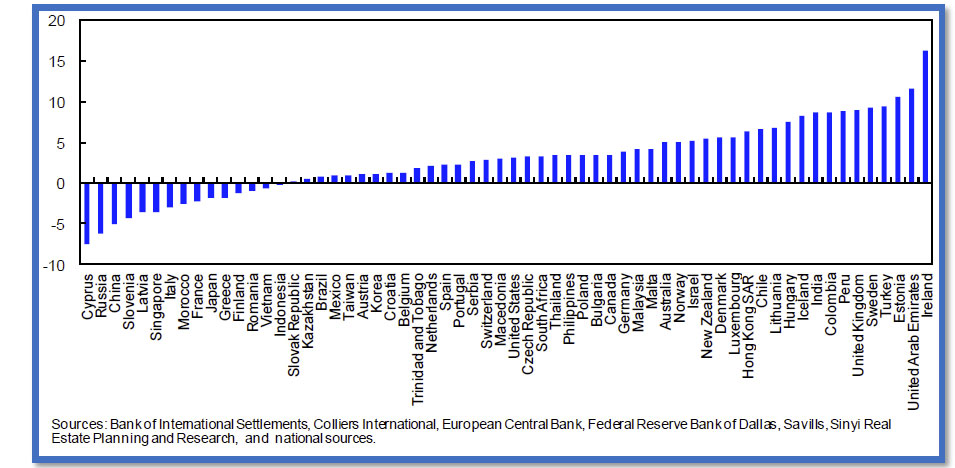

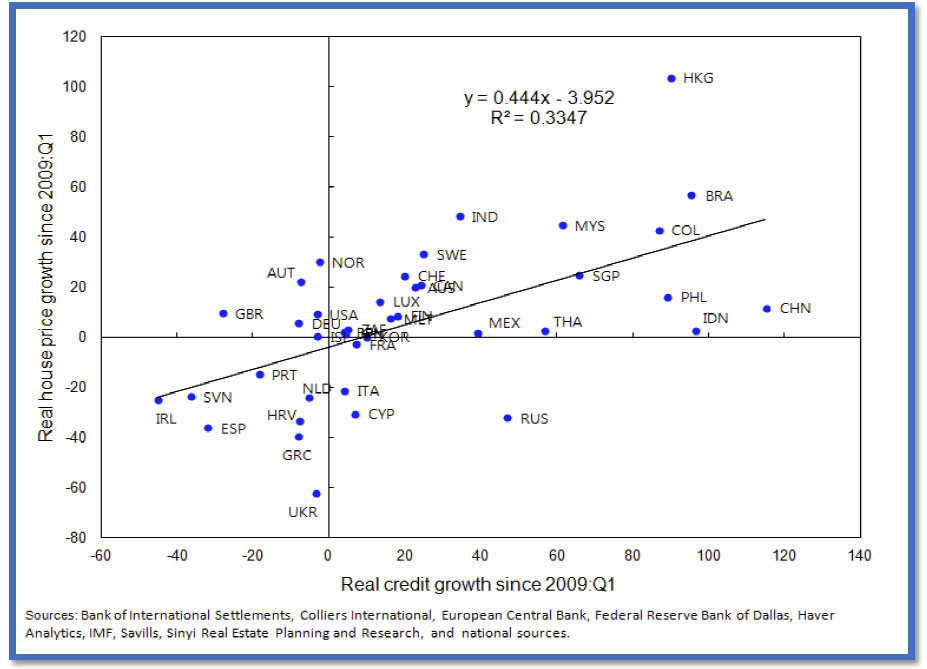

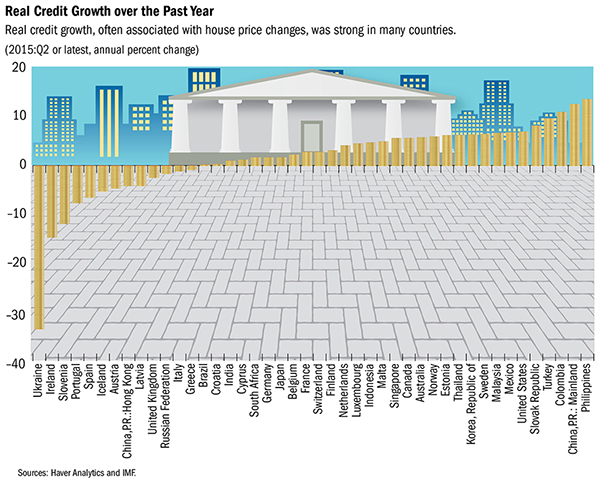

Credit growth has been strong in many countries. As noted in July’s quarterly report, house prices and credit growth have gone hand-in-hand over the past five years. However, credit growth is not the only predictor for the extent of house price growth; several other factors appear to be at play.

Credit growth has been strong in many countries. As noted in July’s quarterly report, house prices and credit growth have gone hand-in-hand over the past five years. However, credit growth is not the only predictor for the extent of house price growth; several other factors appear to be at play.

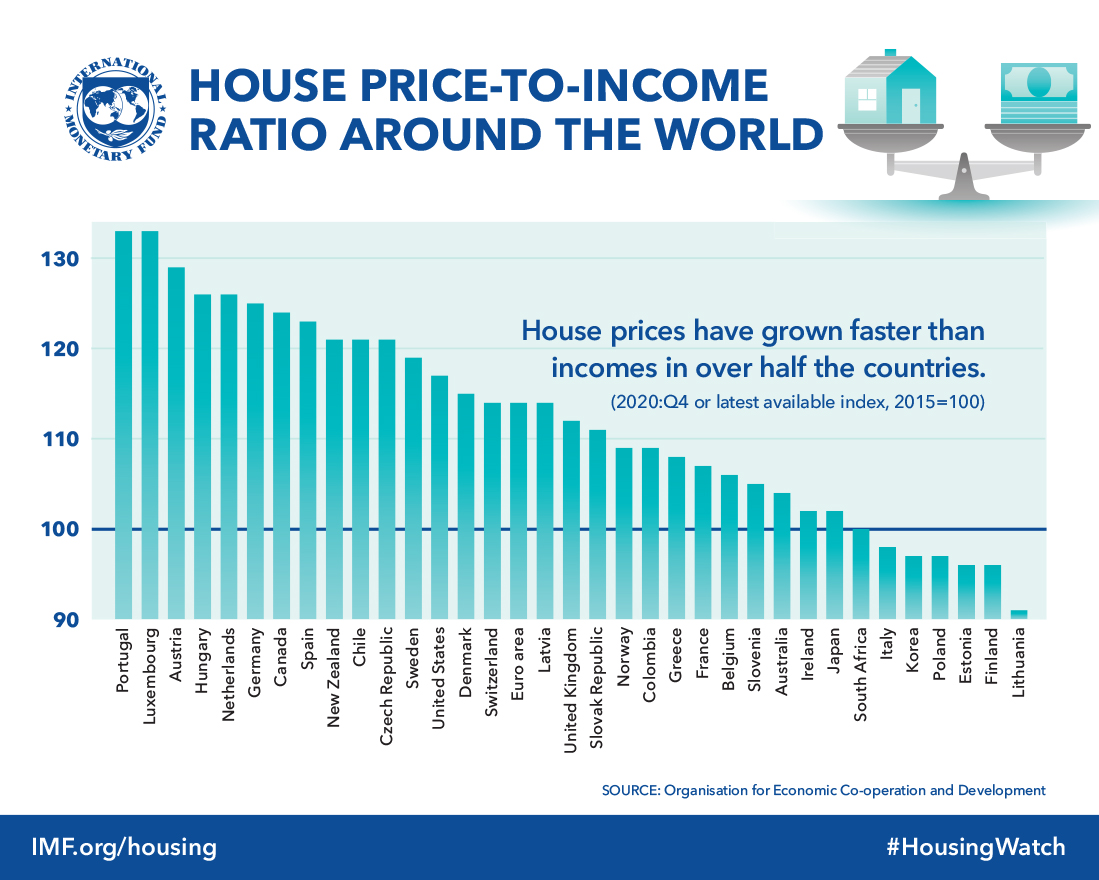

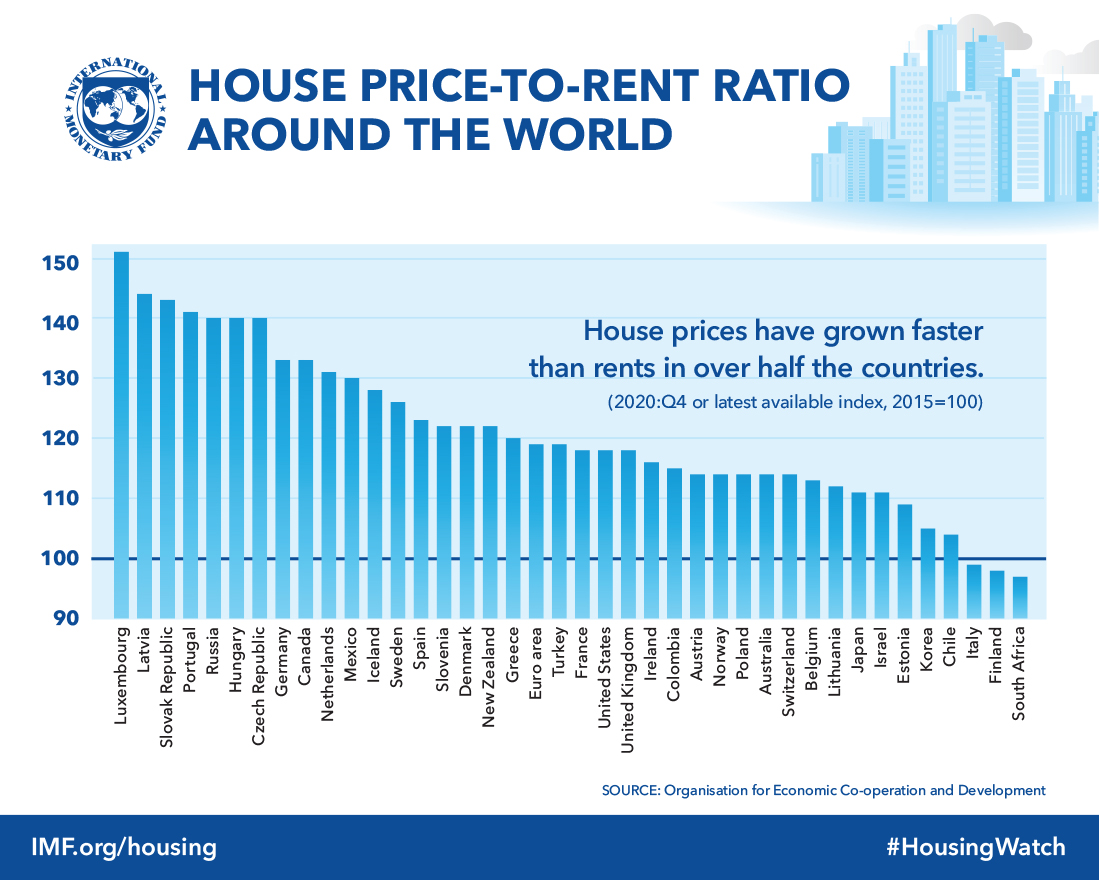

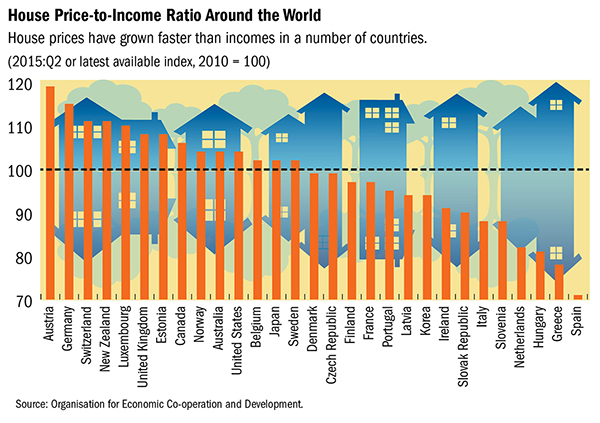

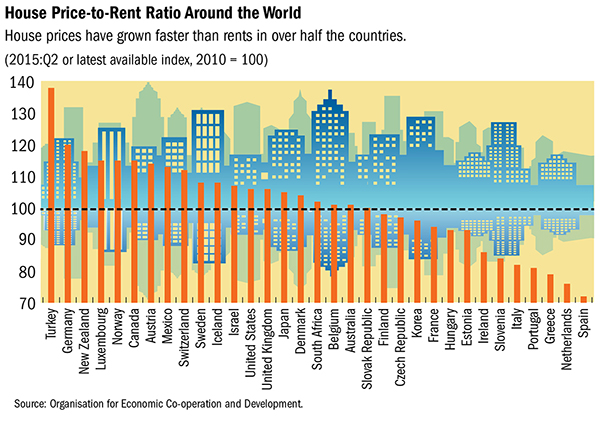

For OECD countries, house prices have grown faster than incomes and rents in almost half of the countries.

For OECD countries, house prices have grown faster than incomes and rents in almost half of the countries.

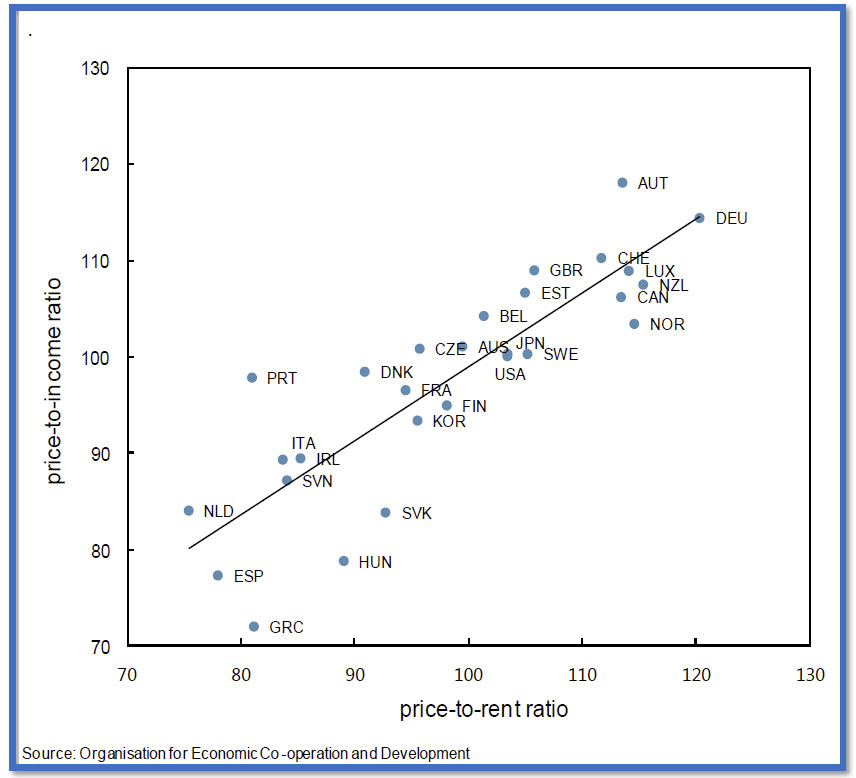

House price-to income and house price-to-rent ratios are highly correlated, as documented in the previous quarterly report.

House price-to income and house price-to-rent ratios are highly correlated, as documented in the previous quarterly report.

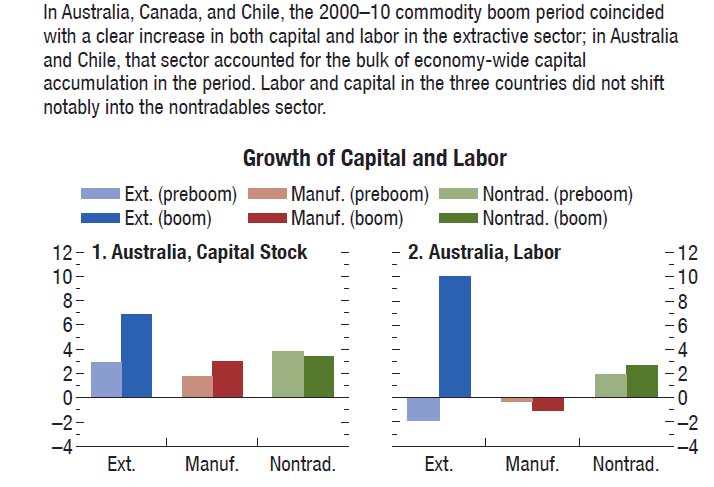

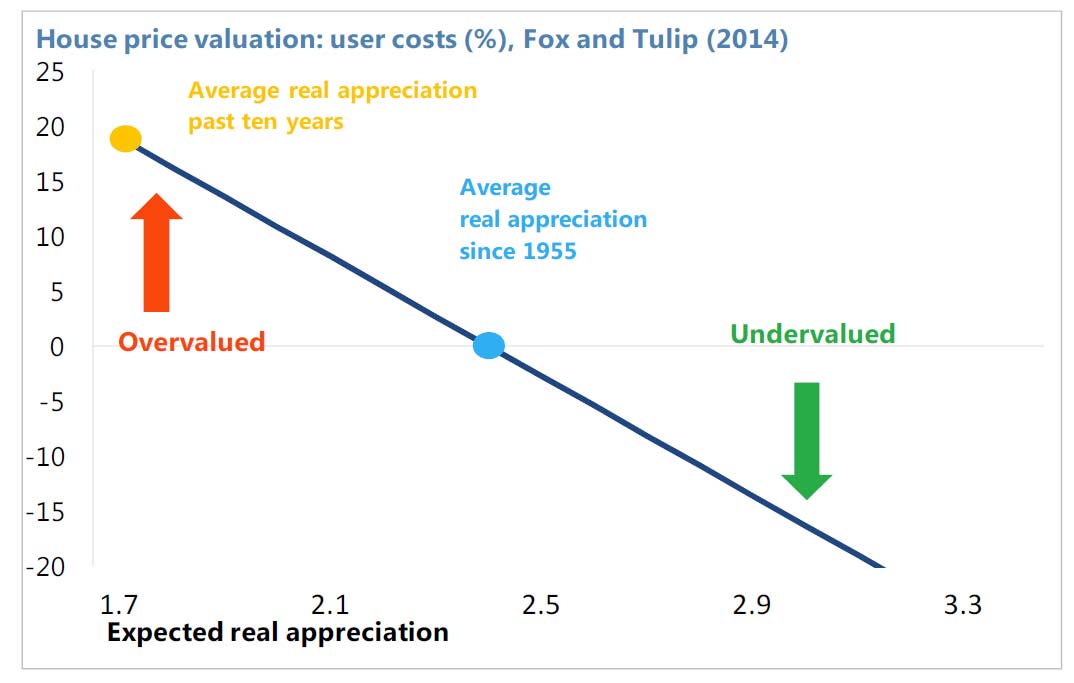

Turning to the Australia specific analysis, Adil Mohommad, Dan Nyberg, and Alex Pitt (all at the IMF) argue that house prices are moderately stronger than consistent with current economic fundamentals, but less than a comparison to historical or international averages would suggest. Here is just a summary of their arguments, the full report is available.

Turning to the Australia specific analysis, Adil Mohommad, Dan Nyberg, and Alex Pitt (all at the IMF) argue that house prices are moderately stronger than consistent with current economic fundamentals, but less than a comparison to historical or international averages would suggest. Here is just a summary of their arguments, the full report is available.

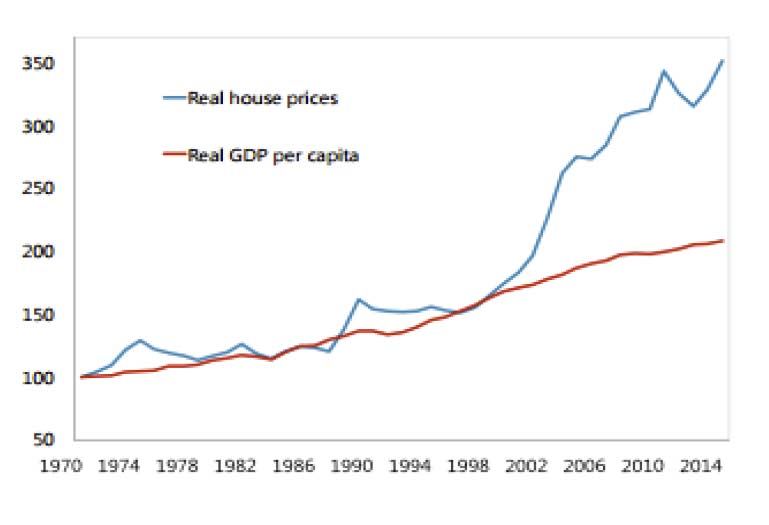

Argument: House prices have risen faster in Australia than in most other countries, suggesting, ceteris paribus, overvaluation.

Counter argument 1: House prices are in line on an absolute basis – Price-to-income ratios have risen in Australia and now near historic highs. However, international comparisons suggest that Australia is broadly in line with comparator countries, although significant data comparability issues make inference difficult.

Counter argument 1: House prices are in line on an absolute basis – Price-to-income ratios have risen in Australia and now near historic highs. However, international comparisons suggest that Australia is broadly in line with comparator countries, although significant data comparability issues make inference difficult.

Counter argument 2: The equilibrium level of house prices has also risen sharply – Lower nominal and real interest rates and financial liberalization are key contributors to the strong increases in house prices over the past two decades. The various house price modeling approaches indicate that house prices are moderately stronger (in the range of 4-19 percent) than economic fundamentals would suggest.

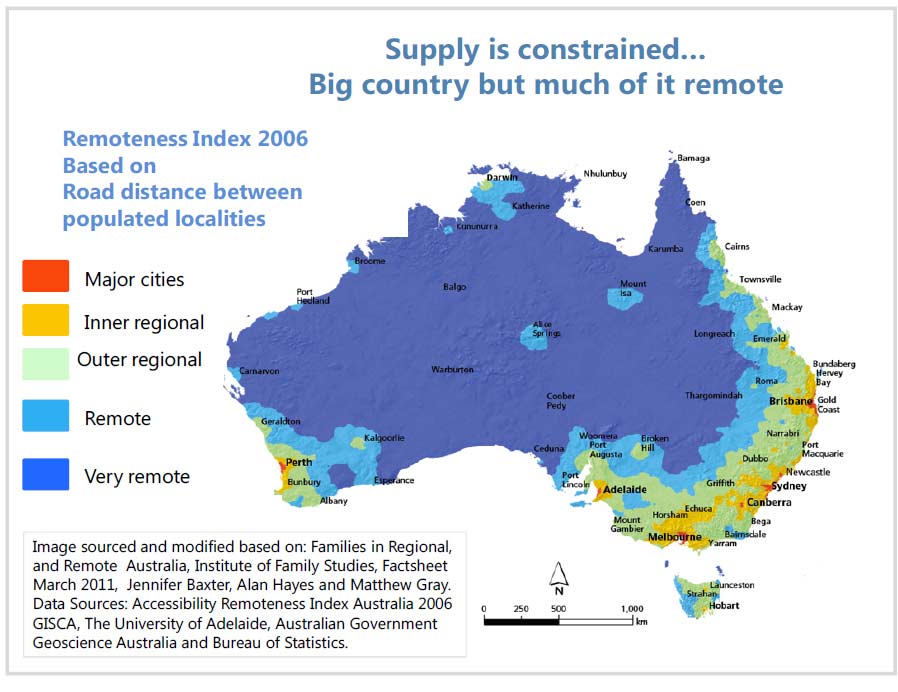

Counter argument 3: High prices reflect low supply – Housing supply does indeed seem to have grown significantly slower than demand, reducing (but not eliminating) concerns about overvaluation.

Counter argument 4: It is just a Sydney problem, not a national one – The two most populous cities, Sydney and Melbourne, have seen strong house price increases, including in the investor segment. A sharp downturn in the housing market in these cities could be expected to have real sector spillovers, pointing to the need for targeted measures—including investor lending—to reduce risks from a housing downturn.

Counter argument 5: There are no signs of weakening lending standards or speculation – While lending standards overall seem not to have loosened, the growing share of investor and interest-only loans in the highly-buoyant Sydney market, is a pocket of concern.

Counter argument 6: Even if they are overvalued, it doesn’t matter as banks can withstand a big fall – While bank capital levels are likely sufficient to keep them solvent in the event of a major fall in house prices, they are not enough to prevent banks making an already extremely difficult macroeconomic situation worse.

Let us think about each in turn.

- First, the financialisation of society is not just an Australian thing (though we have some of the highest household debts in the world), so just because we are following a global trend, does not make it ok.

- Second, we agree, in the main centres, house prices are about 20% over fundamentals, and in some pockets up to 30%, so yes this is a problem, especially at a time of flat income growth.

- Third, supply has been increasing, but this has stoked investment housing speculation, and is not equally strong in all areas and price brackets. We still have a massive under-supply of affordable housing, just ask prospective first time buyers – and many are having to reach for the skies just to buy something, so we thing prices are still hiked because of supply problems.

- Fourth, Sydney and Melbourne markets do indeed seem to be on the turn (and record low interest rates remember), so there is risk.

- Fifth, underwriting standards had declined, refer to recent APRA. ASIC and RBA comments. Guidelines on assessment of income, and baseline interest rate assumptions have been tightened. Speculation is also rife, especially in the investment sector (refer our surveys).

- Sixth, banks are being forced to raise capital because there is risk in the system, and the APRA stress tests showed that whilst individual banks are strong, they had not taken into account the fact that in a downturn, all banks would be trying to access capital markets at the same time and so may not be successful.

Thus, DFA concludes the IMF initial statement is correct, and despite their detailed analysis, their counterarguments are not convincing. We do have a problem.