We look at the latest IMF Financial Stability Report. Where will the systemic risks end up?

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

The latest World Economic Outlook warns of slower growth though sees a possible acceleration later in the year (thanks to the Fed’s recent change in tune!).

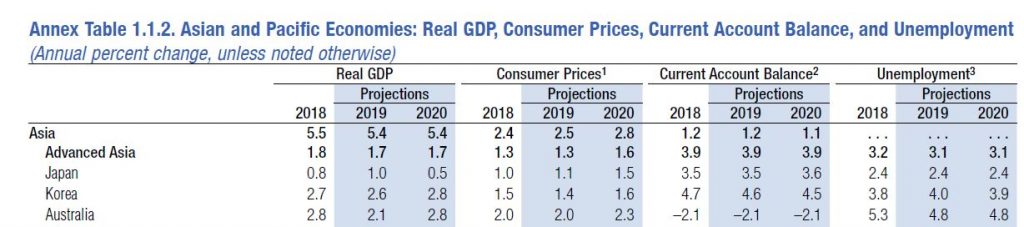

Australian growth is forecast to fall to 2.1% in 2019, with CPI at 2% and unemployment at 4.8%. In 2020, GDP is forecast at 2.8%, CPI 2.3% and unemployment at 4.8%.

One year ago economic activity was accelerating in almost all regions of the world and the global economy was projected to grow at 3.9 percent in 2018 and 2019.

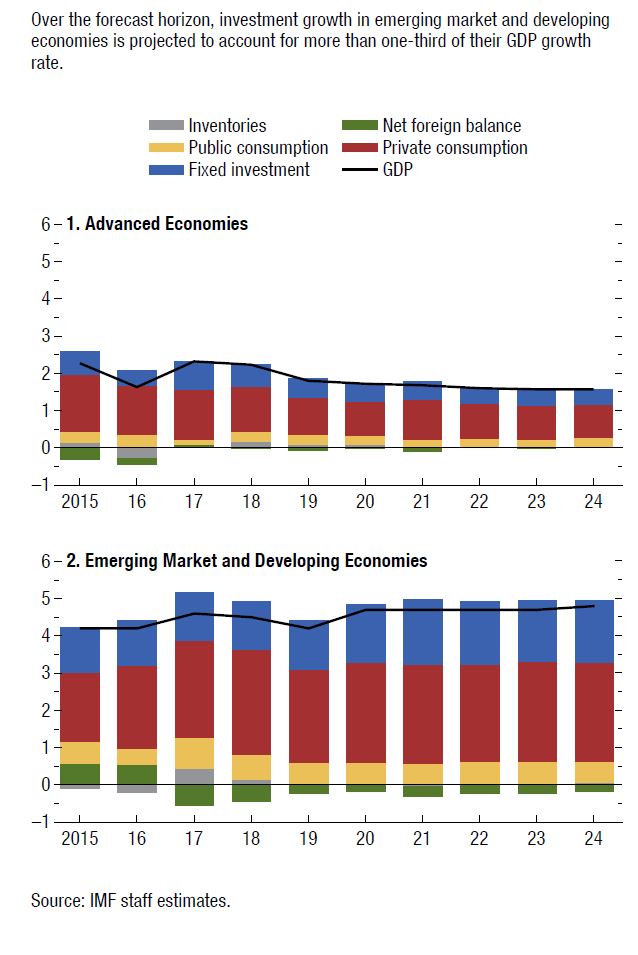

One year later, much has changed: the escalation of US–China trade tensions, macroeconomic stress in Argentina and Turkey, disruptions to the auto sector in Germany, tighter credit policies in China, and financial tightening alongside the normalization of monetary policy in the larger advanced economies have all contributed to a significantly weakened global expansion, especially in the second half of 2018. With this weakness expected to persist into the first half of 2019, the World Economic Outlook (WEO) projects a decline in growth in 2019 for 70 percent of the global economy. Global growth, which peaked at close to 4 percent in 2017, softened to 3.6 percent in 2018, and is projected to decline further to 3.3 percent in 2019. Although a 3.3 percent global expansion is still reasonable, the outlook for many countries is very challenging, with considerable uncertainties in the short term, especially as advanced economy growth rates converge toward their modest long-term potential.

While 2019 started out on a weak footing, a pickup is expected in the second half of the year. This pickup is supported by significant policy accommodation by major economies, made possible by the absence of inflationary pressures despite closing output gaps. The US Federal Reserve, in response to rising global risks, paused interest rate increases and signaled no increases for the rest of the year. The European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, and the Bank of England have all shifted to a more accommodative stance. China has ramped up its fiscal and monetary stimulus to counter the negative effect of trade tariffs. Furthermore, the

outlook for US–China trade tensions has improved as the prospects of a trade agreement take shape. These policy responses have helped reverse the tightening of financial conditions to varying degrees across countries.

Emerging markets have experienced a resumption in portfolio flows, a decline in sovereign borrowing costs, and a strengthening of their currencies relative to the dollar. While the improvement in financial markets has been rapid, those in the real economy have yet to materialize. Measures of industrial production and investment remain weak for most advanced and emerging economies, and global trade has yet to recover. With improvements expected in the second half of 2019, global economic growth in 2020 is projected to return to 3.6 percent. This return is predicated on a rebound in Argentina and Turkey and some improvement in a set of other stressed emerging market and developing economies, and therefore subject to considerable uncertainty. Beyond 2020 growth will stabilize at around 3½ percent, bolstered mainly by growth in China and India and their increasing weights in world income. Growth in advanced economies will continue to slow gradually as the impact of US fiscal stimulus fades and growth tends toward the modest potential for the group, given ageing trends and low productivity growth. Growth in emerging market and developing economies will stabilize at around 5 percent, though with considerable variance between countries as subdued commodity prices and civil strife weaken prospects for some.

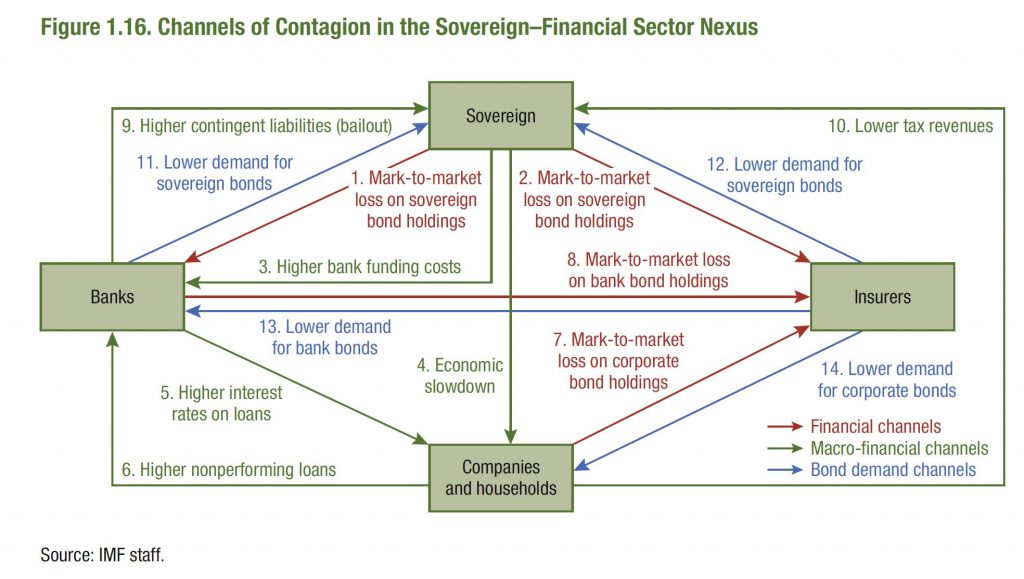

While the overall outlook remains benign, there are many downside risks. There is an uneasy truce on trade policy, as tensions could flare up again and play out in other areas (such as the auto industry) with large disruptions to global supply chains. Growth in China may surprise on the downside, and the risks surrounding Brexit remain heightened. In the face of significant financial vulnerabilities associated with large private and public sector debt in several countries, including sovereign-bank doom loop risks (for example, in Italy), there could be a rapid change in financial conditions owing to, for example, a risk-off episode or a no-deal Brexit.

With weak expansion projected for important parts of the world, a realization of these downside risks could dramatically worsen the outlook. This would take place at a time when conventional monetary and fiscal space is limited as a policy response. It is therefore imperative that costly policy mistakes are avoided. Policymakers need to work cooperatively to help ensure that policy uncertainty doesn’t weaken investment. Fiscal policy will need to manage trade-offs between supporting demand and ensuring that public debt remains on a sustainable path, and the optimal mix will depend on country-specific circumstances. Financial sector policies must address vulnerabilities proactively by deploying macroprudential tools. Low-income commodity exporters should diversify away from commodities given the subdued outlook for commodity prices. Monetary policy should remain data dependent, be well communicated, and ensure that inflation expectations remain anchored.

Across all economies, the imperative is to take actions that boost potential output, improve inclusiveness, and strengthen resilience. A social dialogue across all stakeholders to address inequality and political discontent will benefit economies. There is a need for greater multilateral cooperation to resolve trade conflicts, to address climate change and risks from cybersecurity, and to improve the effectiveness of international taxation.

Until now the IMF has been warning in general terms of the risks from our housing sector, but in a recent working paper – Household Debt, Consumption, and Monetary Policy in Australia, they take the issue significantly further.

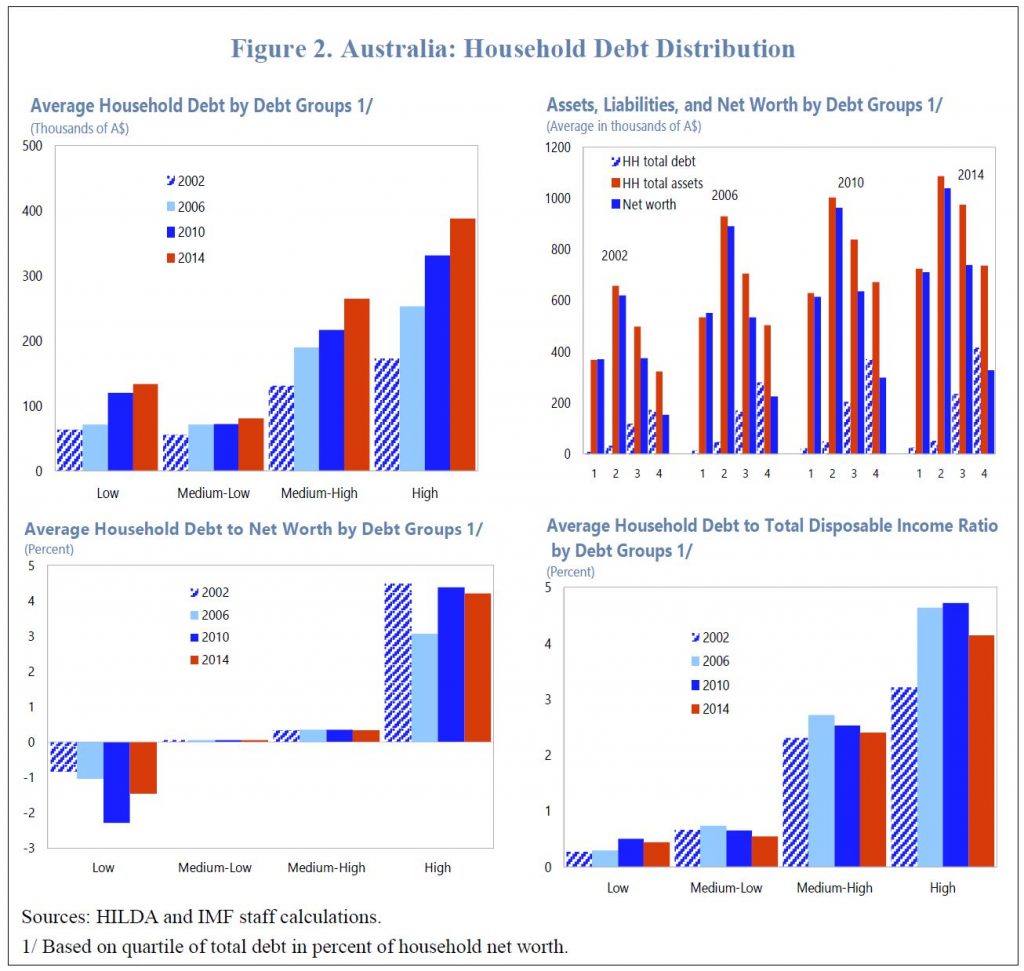

Within its 39 pages, the paper discusses the evolution of the household debt in Australia and finds that while higher-income and higher-wealth households tend to have higher debt, lower-income households may become more vulnerable to rising debt service over time.

Then, the paper analyzes the impact of a monetary policy shock on households’ current consumption and durable expenditures depending on the level of household debt. The results corroborate other work that households’ response to monetary policy shocks depends on their debt and income levels. In particular, households with higher debt tend to reduce their current consumption and durable expenditures more than other households in response to a contractionary monetary policy shocks. However, households with low debt may not respond to monetary policy shocks, as they hold more interest-earning assets.

And we should say at this point that IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

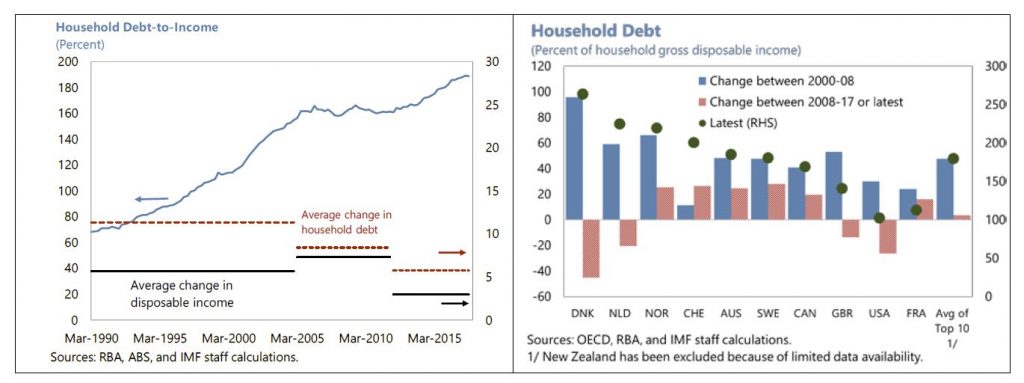

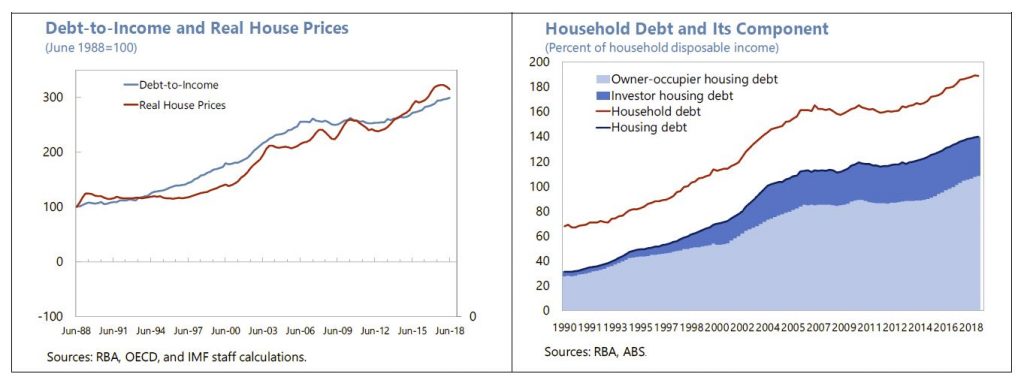

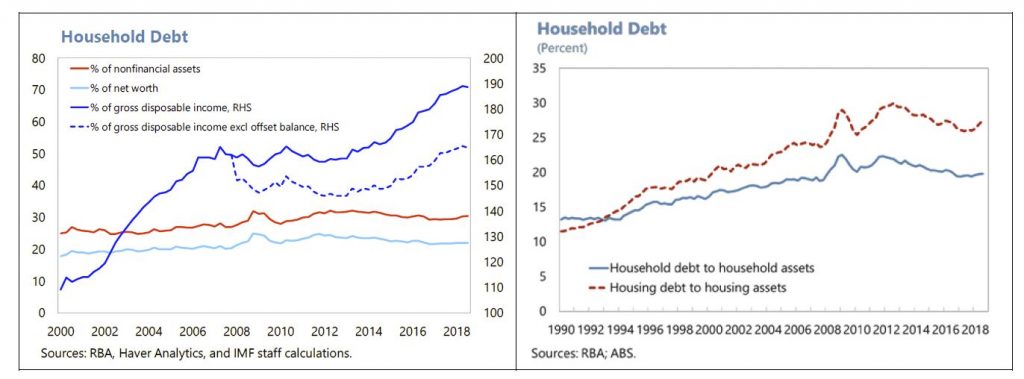

Household debt in Australia has increased to comparatively high levels over the last three decades, a period during which housing prices also have risen rapidly. By end-September 2018, the ratio of household debt to household gross disposable income reached 189 percent, among the highest in advanced economies. High levels of household debt are widely considered to be risky, as they can amplify the impact of external and domestic shocks and, thereby, increase a country’s economic and financial vulnerabilities and pose risks to financial stability. In addition to amplifying financial and economic vulnerabilities, high household debt can also intensify the ongoing corrections in the housing market in Australia.

The macroeconomic impact of and the risks from household debt depend not only on the average debt level but also its distribution across households. Higher-income households might be at lower risk of debt default than lower-income households, for example. The latter might also be more likely to be finance-constrained in times of debt distress. From a monetary policy perspective, a key consideration is the extent to which household debt levels and distribution affect monetary policy transmission.

Household debt in Australia has been rising faster than household disposable income for the past three decades. As a result, the household debt ratio has risen to one of the highest levels among advanced economies.

The housing boom has also played a significant role in the rapid accumulation of household debt. High housing demand due to income and population growth in conjunction with relatively inelastic supply have pushed up house prices, and expectations of future capital gains has encouraged investment demand for housing.

The interaction between the long-term upswing in housing prices and relatively easy mortgage financing has therefore led to the buildup of a high level of residential mortgage debt.

High household debt also reflects the preference for home ownership and housing investment in Australia. Housing debt at 140 percent of household disposable income accounted for about three-quarters of household debt outstanding as of September 2018, with owner-occupied housing debt accounting for a relatively stable share of about one half.

The rise in the share of investor housing debt since 2000 has also contributed to the fast increase in household debt, while other personal debt has remained broadly stable (one quarter of household debt outstanding) at about 46 percent of household disposable income since 2000.

For financial stability, as well as monetary and macroprudential policies, it is not only the level of household debt that matters but also the speed of debt accumulation or leverage increases, the extent of leverage, and, more importantly, the distribution of debt.

The IMF uses old data, from the HILDA survey, which has been running with annual frequency from 2001 to 2016 to make their assessment – clearly the debt position has deteriorated since then, yet they show that debt has grow across the cohorts and segments. The RBA analysis has the same fundamental flaw.

The paper finds that high debt exposure is more prevalent among higher-income and higher-wealth households. Nevertheless, the debt exposure of lower-income and more vulnerable households has also increased over time, and thereby more exposed to risks from rising debt service. The presence of over-indebted households at both low- and higher-income quintiles suggests that macro-financial risks have increased, suggesting a need for close monitoring.

Despite the high debt level, households’ debt service burden has remained manageable due to historical low mortgage interest rates and given that financial institutions assess mortgage serviceability for new mortgage lending with interest rate buffers above the effective variable rate applied for the term of the loans. However, downside risks on debt service capacity and consumption remain with regards to a sharp tightening of global financial conditions which could spill over to higher domestic interest rates.

The empirical analysis investigates the transmission of monetary policy shocks to the current consumption and durable expenditures of households with different debt-to-wealth ratios. With reasonable assumptions and using the large sample of households available in the HILDA survey for 2001-16, the results corroborate that households’ response to monetary policy shocks will vary, depending on both their debt and income levels.

In particular, the results suggest that households with high debt tend to reduce their current consumption and durable expenditures relatively more than other households in response to a contractionary monetary policy shocks. At the same time, households with low debt may not respond to monetary policy shocks, as they hold more interest-earning assets and thereby can smooth their consumption using the higher interest income, suggesting that for these households, the income effect dominates the intertemporal substitution effect.

The results of the analysis suggest that, with a larger share of high-debt households and given their high responsiveness to a monetary policy shock, it may take a smaller increase in the cash rate for the RBA to achieve its policy objectives, compared to past episodes of policy rate adjustments. It corroborates recent RBA research, which suggests that the level and the distribution of the household debt will likely alter monetary policy transmission, in other words, more bang for the buck. By responding gradually, the RBA can still meet its mandates.

The implications of higher household debt for monetary policy have also required that the RBA addresses this challenges in its communication. The results of the textual analysis show that the RBA’s communication has increasingly focused on the impact of household debt on monetary conditions and financial stability over the past decade, consistent with the rise in debt-to-income ratios. Markets have also started to take into account household debt in their assessment of monetary policy and market expectation analysis. Therefore, continuing with a transparent and strengthened communication strategy on issues related to the household debt and household consumption will further improve predictability and efficiency of monetary policy in Australia.

My take is the household debt burden is larger, and more exposed to potential risks than many accept. Nothing new perhaps, but the IMF highlighting the issues is one more piece of the too-high debt narrative!

And according to the AFR, in an exclusive interview, the International Monetary Fund’s lead economist for Australia, Thomas Helbling said Australia’s housing market contraction is worse than first thought, leaving the economy in what he called a “delicate situation” that boosts the need for faster infrastructure spending and even potential interest rate cuts.

Australia’s housing market contraction is worse than first thought!

David Lipton, the deputy director of the Washington-based International Monetary Fund, delivered a stark warning about the depleted power of central banks and governments to combat another sharp economic shock.

“ The bottom line is this: the tools used to confront the Global Financial Crisis may not be available or may not be as potent next time. The space for additional monetary policy accommodation will surely be more constrained; fiscal resources may not be as available in many countries; and political resistance to bailouts may be greater because many people feel that those who brought about the last crisis did not shoulder their share of the burden.”

So, in short, the emergency tool kit that helped to pull the global economy out of the Great Financial Crisis might not work a second time, the world’s lender of last resort has warned.

Global Challenges

Obviously, this is not a matter for Europe alone. The U.S. needs to get its fiscal house in order as well. U.S.-China trade tensions pose the largest risk to global stability. Beijing needs to continue its shift toward high-quality growth and should support a sustainable globalization. All emerging markets should face up to external shocks and volatile capital flows.

While most baseline forecasts show some recovery ahead for Europe, many have been surprised by the size and pace of the recent deceleration. So, it is important to acknowledge the continuing uncertainty about the coming year, including with the crucial issue of Brexit still unresolved.

Each country should act now to strengthen their defenses ahead of a potential downturn. That includes those who have not addressed glaring vulnerabilities, most notably Italy. A serious recession could be very damaging for these countries, because they will be shown to be ill prepared. Their weaknesses could present a serious setback for Europe’s goal of convergence—of standards of living, productivity, of national well-being.

On the other hand, there are countries that are in a strong position to face a downturn—most notably Germany.

He warned that many countries need to drive reforms to deal with the emerging risks.

Economist John Adams and Analyst Martin North discuss the latest on Deposit Bail-In and John reveals its all been done before.

From Investor Daily. An excellent piece by James Mitchell.

The International Monetary Fund has recommended that APRA takes a forensic “deep dive” into the credit risk management frameworks of Australian banks.

The IMF has released its Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) report on Australia. While the comprehensive review was generally positive towards the domestic economy and the role of the prudential regulator, it did warn of key risks to the financial system.

The IMF noted that stretched real estate valuations and high household debt pose macro-prudential risks to Australia.

“House prices, after rising by about 70 per cent over the past decade at the national level, have now started to decline,” the report said.

“The price appreciation following the global financial crisis had been even higher in Sydney and Melbourne, where prices had doubled on average over 10 years, though these two cities have also experienced sharper falls in recent months.

“Commercial real estate prices, particularly for office space, also rose sharply in the major cities over the past decade but have shown few signs of cooling as yet. Housing affordability linking incomes to prices is near all-time lows.”

The IMF noted that in recent years, benign credit conditions and the surge in house prices contributed to rapidly rising household leverage. Household debt currently stands at some 190 per cent of disposable income, around 25 basis points higher than in 2012, when the last FSAP report was produced.

The report noted that this is “very high by international standards”. Australian household debt-to-income levels are now almost twice as high as the United States and Japan and exceed the levels in the UK and Canada.

While macro-prudential measures have contributed to the easing of pressures in the housing market, and a soft landing of the housing market is the most likely baseline, the IMF warned that there are risks of a stronger downturn.

“A sharp correction in real estate markets could lead to a vicious feedback loop of falling real estate valuations, higher nonperforming loans, tighter bank credit, falling consumer confidence, and weaker growth, as happened during the global financial crisis (GFC),” the report said.

“The impact on banks would be largely through credit losses as they all carry large exposures to the housing market and to CRE. Additionally, weaker banks could experience an outflow of customer deposits or a significant decline in wholesale funding.”

The IMF has recommended that APRA supervisors should continue scrutinising banks’ underwriting practices, particularly in retail loans (including residential mortgages) and in the commercial real estate lending sector.

Critically, the report recommends that APRA supervisors should consider undertaking periodic deep dives into banks’ credit risk management framework depending on the risks and controls of ADIs.

In addition to house prices and household debt, Australia’s financial system could be significantly impacted by a slowdown in China, the report warned.

Rising global protectionism could provide one catalyst.

“While Australian banks’ direct exposure to China is relatively small (about 4 per cent of overall claims), the economy has much larger exposure via the trade channel,” the report said.

“One-third of Australian goods exports, including 40 per cent of commodities, go to China. Moreover, the growth of services exports to China in recent years has been particularly strong in the areas of tourism and education.

“A sharp slowdown in Chinese growth would lower Australian export revenues markedly. Banks would likely face higher losses on corporate lending, as well as on their broader credit portfolio due to the overall decline in economic activity.”

In its review of the Australian banking sector, the IMF observed that while ADIs are reasonably liquid, profitable and well capitalised, they have oriented their business models towards residential lending in recent years.

While the IMF noted APRA’s efforts to cool residential lending via macro-prudential measures in recent years, the report noted that “significant structural vulnerabilities persist in the financial system”.

“Household indebtedness remains very high, while banks’ portfolios continue to be concentrated and heavily exposed to the residential mortgage sector.

“Banks are exposed to rollover risk on their overseas funding. Wholesale funding dependence has diminished but remains around one-third of total funding, of which nearly two-thirds is from international sources.”

The IMF noted that the Australian tax system provides incentives for leveraged investment by households, including in residential real estate that contributes to the elevated structural vulnerabilities.

“There are also few signs of cooling in the commercial real estate sector where prices have risen sharply in recent years. While bank exposures to the sector are significantly smaller than to households, the sector is highly cyclical and typically experiences high default rates during severe downturns.”

The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook Update, January 2019, says that global growth in 2018 is estimated to be 3.7 percent, as it was last fall, but signs of a slowdown in the second half of 2018 have led to downward revisions for several economies. Specifically, growth in advanced economies is projected to slow from an estimated 2.3 percent in 2018 to 2.0 percent in 2019 and 1.7 percent in 2020.

Weakness in the second half of 2018 will carry over to coming quarters, with global growth projected to decline to 3.5 percent in 2019 before picking up slightly to 3.6 percent in 2020 (0.2 percentage point and 0.1 percentage point lower, respectively, than in the previous WEO). This growth pattern reflects a persistent decline in the growth rate of advanced economies from above-trend levels—occurring more rapidly than previously anticipated—together with a temporary decline in the growth rate for emerging market and developing economies in 2019, reflecting contractions in Argentina and Turkey, as well as the impact of trade actions on China and other Asian economies.

Specifically, growth in advanced economies is projected to slow from an estimated 2.3 percent in 2018 to 2.0 percent in 2019 and 1.7 percent in 2020. This estimated growth rate for 2018 and the projection for 2019 are 0.1 percentage point lower than in the October 2018 WEO, mostly due to downward revisions for the euro area.

For the emerging market and developing economy group, growth is expected to tick down to 4.5 percent in 2019 (from 4.6 percent in 2018), before improving to 4.9 percent in 2020. The projection for 2019 is 0.2 percentage point lower than in the October 2018 WEO.

Risks to the Outlook

Key sources of risk to the global outlook are the outcome of trade negotiations and the direction financial conditions will take in months ahead. If countries resolve their differences without raising distortive trade barriers further and market sentiment recovers, then improved confidence and easier financial conditions could reinforce each other to lift growth above the baseline forecast. However, the balance of risks remains skewed to the downside, as in the October WEO.

Trade tensions. The November 30 signing of the US-Mexico-Canada free trade agreement (USMCA) to replace NAFTA, the December 1 US-China announcement of a 90-day “truce” on tariff increases, and the announced reduction in Chinese tariffs on US car imports are welcome steps toward de-escalating trade frictions. Final outcomes remain, however, subject to a possibly difficult negotiation process in the case of the US-China dispute and domestic ratification processes for the USMCA. Thus, global trade, investment, and output remain under threat from policy uncertainty, as well as from other ongoing trade tensions. Failure to resolve differences and a resulting increase in tariff barriers would lead to higher costs of imported intermediate and capital goods and higher final goods prices for consumers. Beyond these direct impacts, higher trade policy uncertainty and concerns over escalation and retaliation would lower business investment, disrupt supply chains, and slow productivity growth. The resulting depressed outlook for corporate profitability could dent financial market sentiment and further dampen growth (Scenario Box 1, October 2018 WEO).

Financial market sentiment. Escalating trade tensions, together with concerns about Italian fiscal policy, worries regarding several emerging markets, and, toward the end of the year, about a US government shutdown, contributed to equity price declines during the second half of 2018. A range of catalyzing events in key systemic economies could spark a broader deterioration in investor sentiment and a sudden, sharp repricing of assets amid elevated debt burdens. Global growth would likely fall short of the baseline projection if any such events were to materialize and trigger a generalized risk-off episode:

Beyond the possibility of escalating trade tensions and a broader turn in financial market sentiment, other factors adding downside risk to global investment and growth include uncertainty about the policy agenda of new administrations, a protracted US federal government shutdown, as well as geopolitical tensions in the Middle East and East Asia. Risks of a somewhat slower-moving nature include pervasive effects of climate change and ongoing declines in trust of established institutions and political parties.

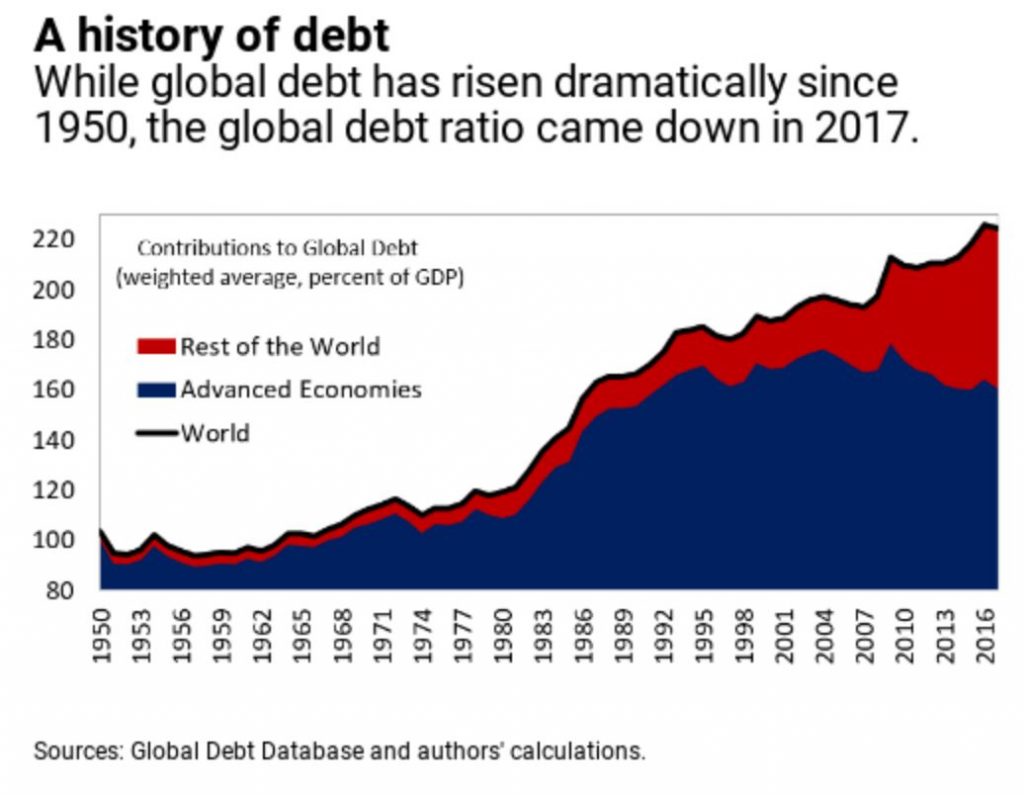

The IMF has updated their Global Debt Database, and by including both the government and private sides of borrowing for the entire world, it offers an unprecedented picture of global debt in the post-World War II era.

The long view

Was 2017 different?

For 2017, the signals are mixed. Compared to the previous peak in 2009, the world is now more than 11 percentage points of GDP deeper in debt. Nonetheless, in 2017 the global debt ratio fell by close to 1½ percent of GDP compared to a year earlier. The last time the world witnessed a similar decline was in 2010, although it proved short-lived. However, it is not yet clear whether this is a hiatus in an otherwise uninterrupted ascending trend or if countries have begun a longer process to shed more debt. New country data available later in 2019 will tell us more about the global debt picture. For 2017, we divided up countries into three groups based on their debt profile and here’s what we found:

Overall, the picture of global debt has changed as the world has changed. The data shows that a big part of the decline in the global debt ratio is the result of the waning importance of heavily-indebted advanced economies in the world economy.

With financial conditions tightening in many countries, which includes rising interest rates, prospects for bringing debt down remain uncertain. The high levels of corporate and government debt built up over years of easy global financial conditions, which the Fiscal Monitor documents, constitute a potential fault line.

So, as we close the first decade after the global financial crisis, the legacy of excessive debt still looms large.

The IMF has released their Concluding Statement of the 2018 Article IV Consultation Mission. And, well, it gives a relatively clean bill of health, whilst talking of risks in the housing sector, a need for more financial risk oversight and suggests that supply side issues need to be addressed to ease affordability. In other words they are following the RBA mantra, no household debt problem here and APRA’s bank capital is unquestionably strong! We will see.

A Concluding Statement describes the preliminary findings of IMF staff at the end of an official staff visit (or ‘mission’), in most cases to a member country. Missions are undertaken as part of regular (usually annual) consultations under Article IV of the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, in the context of a request to use IMF resources (borrow from the IMF), as part of discussions of staff monitored programs, or as part of other staff monitoring of economic developments.

The authorities have consented to the publication of this statement. The views expressed in this statement are those of the IMF staff and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF’s Executive Board. Based on the preliminary findings of this mission, staff will prepare a report that, subject to management approval, will be presented to the IMF Executive Board for discussion and decision.

Australia is now on the final leg of its rebalancing and adjustment after the end of the commodity price and mining investment boom. Growth has picked up strongly to well above 3 percent in 2018, driven by business investment and private consumption, while the recent rebound in the terms of trade has been sustained. The strong economic momentum has resulted in further improvements in labor market conditions. Nonetheless, wage growth has remained weak, suggesting some remaining labor market slack. The disinflationary effects from continued strong retail competition still weigh on core inflation, while one-off declines in some administered prices have temporarily lowered headline inflation. After rising by 70 percent in the past ten years at the national level and by roughly 100 percent in Sydney and 90 percent in Melbourne, house prices have moderated recently in a cooling housing market. Several factors have contributed to the cooling, including tightening credit supply, increasing housing supply coming to the market, and easing foreign demand. Market dynamics have adjusted in the process.

The economy’s strong growth momentum is expected to continue in the near term. Private consumption growth is anticipated to remain buoyant, supported by strong employment gains. The rebound in non-mining private business investment and further growth in public investment is envisaged to offset a softening in dwelling investment. With growth above potential, the output gap will close and labor market slack will erode, eventually leading to upward pressure on wages and prices. Macroeconomic policies will then adjust, and growth is expected to moderate to that of potential in the medium term.

The balance of risks to economic growth is tilted to the downside with a less favorable global risk picture. A weaker-than-expected near-term outlook in China coupled with further rising global protectionism and trade tensions could delay full closure of the output gap, although there are also upside risks to the terms of trade in the near term. A sharp tightening of global financial conditions could spill over into domestic financial markets, raising funding costs and lowering disposable income of debtors, with the impact also depending on the response of the Australian dollar. On the domestic side, a stronger pickup in the non-mining business sector, larger spillovers from public infrastructure investment, and the Australian dollar depreciation in real effective terms over the past year could boost near-term growth more than projected. Domestic demand may equally turn out weaker if wage growth remained subdued or investment spillovers were smaller.

The housing market downturn is another source of risk. Under the baseline outlook, the correction remains orderly, reflecting a combination of continued strong underlying demand for housing in the context of population growth and no significant oversupply, the presence of other strong growth drivers, and a resilient banking sector continuing to extend credit to support economic growth. Nevertheless, other negative risk developments, as outlined above, could amplify the correction and lower domestic demand.

Notwithstanding recent strong growth, it is not yet the time to withdraw macroeconomic policy support given remaining slack. With the cash rate at 1.5 percent, monetary policy remains appropriately accommodative. Normalization should remain conditional on evidence of more substantive upward pressures on wages and prices, as inflation is still below the target range. The broadly neutral fiscal policy stance is welcome. With more limited conventional monetary policy space, a fiscal stimulus would likely need to be part of an effective overall policy response if major downside risks materialized.

With the economy expected to return to full employment, the government’s medium-term fiscal strategy appropriately aims to reach budget balance by FY2019/20 and run budget surpluses thereafter. Under the baseline outlook, this fiscal path would still be consistent with the Commonwealth and state governments continuing to run ambitious infrastructure investment programs and structural reforms in support of higher growth. The principle of running budget surpluses in good times has been a core element of fiscal strategies required under Australia’s fiscal framework, which has helped in preserving fiscal discipline and substantial fiscal space, notwithstanding shocks with protracted effects. Given the fiscal space, Australia remains in a position to respond flexibly in case large downside risks should materialize. A role for medium-term debt anchors as a complementary element in fiscal strategies might also be considered.

The Australian banks are well capitalized and profitable. Following the requirement for capital to be unquestionably strong, banks’ capital levels are high in relation to international comparators.

Managing financial vulnerabilities and risks from high household debt requires macroprudential policy to hold the course. Earlier prudential intervention by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority has lowered the risks to financial stability from higher-risk household debt and other vulnerabilities, in particular reducing the share of investor and interest-only borrowing. This has supported the strengthening of lending standards and the increase in bank resilience. Nevertheless, heightened systemic risks remain from high household debt levels and banks’ concentrated exposure to mortgage lending. Given prospects of interest rates remaining low for some time, macroprudential policy should focus on expanding the available toolkit by addressing any data, legal and regulatory requirements and thus enhancing readiness to implement such measures if and when needed.

The Australian authorities have developed a robust regulatory framework, but further reinforcement in two broad domains would be beneficial.

- The systemic risk oversight of the financial sector could be strengthened. The IMF’s Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) recommends buttressing the financial stability framework by strengthening the transparency of the work of the Council of Financial Regulators on the identification of systemic risks and actions taken to mitigate them. Improving the granularity and consistency of data collection and provision would support the analysis of systemic risks and formulation of policy.

- Financial supervision and financial crisis management arrangements should be further bolstered. The FSAP’s specific recommendations include increasing the independence and budgetary autonomy of the regulatory agencies, strengthening the supervisory approach, particularly in the areas of governance, risk management, and conduct, and enhancing the stress testing framework for solvency, liquidity, and contagion risks. The FSAP also recommends strengthening the integration of systemic risk analysis and stress testing into supervisory processes, completing the resolution policy framework and expediting the development of bank-specific resolution plans. Recent announcements of additional funding for the regulatory agencies are welcome.

The cooling of the housing market is welcome and contributes to improving housing affordability. In the absence of a sharp rise in unemployment, interest rates, or housing inventories, an orderly correction in housing prices will help contain macro-financial vulnerabilities. Pressures on housing affordability, which is critical for growth to remain inclusive, will be relieved in the process.

Housing supply reforms will be critical to restoring housing affordability, and progress has been ongoing. Planning, zoning, and other reforms affect supply and prices only with long lags, and underlying demand for housing is expected to remain robust. Housing supply reforms should, therefore, not be delayed because of the housing market correction. Progress has been made through better integration of policies across government levels through “city deals,” including for western Sydney and its new airport, and for Darwin. Some states should still take the opportunity for further consolidation in planning and zoning regulation. These policy efforts should be complemented by broader tax reforms that also address housing and land use. Such reforms would strengthen the effectiveness of supply-side measures and reduce structural incentives for leveraged investment by households, including in residential real estate.

There is scope to expand infrastructure spending further to stimulate productivity. Australia is a fast-growing economy supported by high population growth, and its infrastructure needs are also increasing rapidly. Even with the recent increase in the infrastructure spending envelope, an infrastructure gap will remain. Reducing the gap further would help in lowering congestion and increase the economy’s potential in the long term, as would improving the effective use of existing infrastructure. The improvements that have been made in the institutional framework for infrastructure planning and assessment support policy efforts in this respect.

Recent policy decisions should help encourage innovation. A reform of the research and development (R&D) tax credit system is with Parliament, aiming for a more efficient and targeted use of the tax credit. It will be complemented by higher funding for research infrastructure. The recommendations of the science agenda laid out in Australia 2030: Prosperity through Innovation are constructive and should be implemented, as envisaged in the government’s response to the report.

Energy policy should further reduce uncertainty for investment decisions. Governments have already made substantial progress on pricing and reliability issues. The clarification in due course of policies to achieve Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions target commitments will also help reduce uncertainty.

Broad tax reform to support productivity and inclusive growth would be desirable. The share of direct taxes in Australia’s federal tax revenue is higher than the average of OECD economies, and shifting from direct to indirect taxes would lower tax distortions and enhance productivity. The Commonwealth government has to date lowered company tax rates for SMEs and introduced personal income tax cuts. These reforms should be combined with reforms to raise the GST revenue, lower the company tax rate more broadly, and reduce tax concessions. To offset the regressive element from higher GST revenue, an income tax-based rebate scheme to reduce the negative impact on lower income groups should be considered.

Australia’s continued efforts toward further trade liberalization and promoting the global multilateral trading system are welcome. This includes supporting new WTO agreements and modernization efforts. The formal ratification of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (also known as CPTPP or TPP-11), which replaces the Trans-Pacific Partnership, sends a positive signal in a time of increasing global trade tensions

We look at reports from the BIS and IMF, and discuss the issues around bail-in, including of deposits.

If you value our content please consider supporting our work via our Patreon page.