Let me start with a warm welcome to everyone who has travelled here to be part of this event. A little over two hundred years ago this beautiful location was seen as an ideal place for a penal colony. Thankfully, Sydney is no longer regarded as a hardship destination, but as someone who does a reasonable amount of international travel, I know it is still quite some distance from wherever you have journeyed from. I hope you are finding the travel to be worth it.

A few quick words about APRA. We are Australia’s prudential regulator, responsible for the prudential oversight of deposit-taking institutions; life, general, and private health insurers; and most of Australia’s superannuation assets. All up, we have coverage of just under $6 trillion in assets, which represents around 3-and-a-half times Australian GDP.

That broad coverage of the financial sector means we inevitably have a large agenda of issues on our plate, but we also have the relative luxury of working with a financial system that is fundamentally sound. To the extent we are grappling with current issues and policy questions, they don’t reflect an impaired system that needs urgent remedial attention, but rather a desire to make the system stronger and more resilient while it is in good shape to do so.

Our mission is to achieve safety within a stable, open, efficient and competitive financial system. We don’t pursue a safety-at-all-costs strategy. But it is also pretty clear the Australian financial system has benefited over the long run from operating with fairly conservative policy and financial settings.

To give you an example, the headline capital ratios of the major Australian banks might seem low relative to international peers – collectively, they have a CET1 ratio of a touch over 9-and-a-half per cent, whereas a more normal expectation in this day and age might be something comfortably in double digits. But the Australian ratios reflect a set of conservative policy decisions that produce a lower headline capital ratio, but give us a much greater level of confidence in the financial health of the banking system.

One result of that approach is that, even though the major Australian banks are either just inside, or just outside, the top 50 banks in the world when ranked by asset size, they are amongst the small number who have retained AA credit ratings, and we have one bank in the top 10, and the remainder in or around the top 20, when ranked by market capitalisation. Clearly, investors – both debt and equity – understand their underlying quality, and the Australian community gets great benefit from the market access that provides.

The Financial System Inquiry held a couple of years ago endorsed our approach, as did the Government in its response to the Inquiry’s recommendations.

So with that background, let me turn to a few of the important issues on our plate.

The main policy item we have on our agenda in 2017 is the first recommendation of the Financial System Inquiry: that we should set capital standards so that the capital ratios of our deposit-takers are ‘unquestionably strong.’ We have been doing quite a bit of thinking on this issue, but had held off taking action until the international work in Basel on the bank capital regime had been completed.

Unfortunately, the timetable for that Basel work now seems less certain, so it would be remiss of us to wait any longer.

We will have more to say in the coming months about how we propose to give effect to the concept of unquestionably strong, but in the meantime the banking industry has been assiduously building its capital strength in anticipation. Looking through the effects of policy changes, the major banks have added in the order of 150 basis points to their CET1 ratios over the past couple of years. Assuming the industry continues to steadily build its capital, we expect it will be well placed to respond to future policy changes in an orderly manner.

If capital for the banking system is our main policy item, then housing is our main supervisory focus. I know there is always a great deal of interest in the Australian housing market, so it is probably something I should say a few words about.

It should not be surprising we have been paying particular attention to the quality of housing portfolios for some time – and particularly the quality of new lending – given housing represents the largest asset class on the banking industry’s balance sheet.

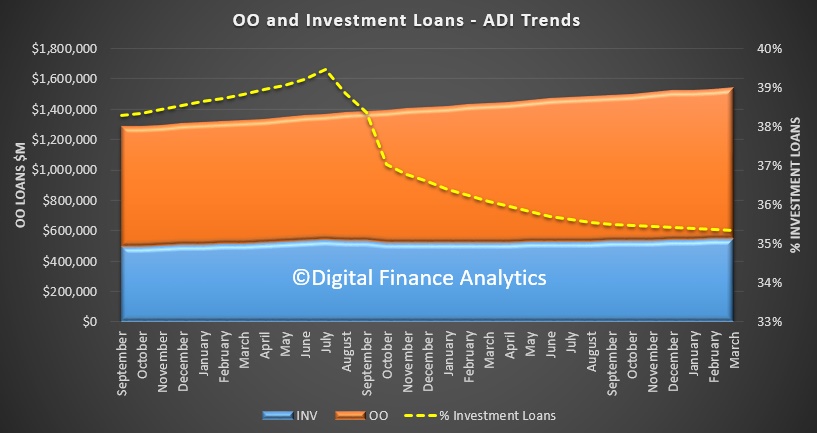

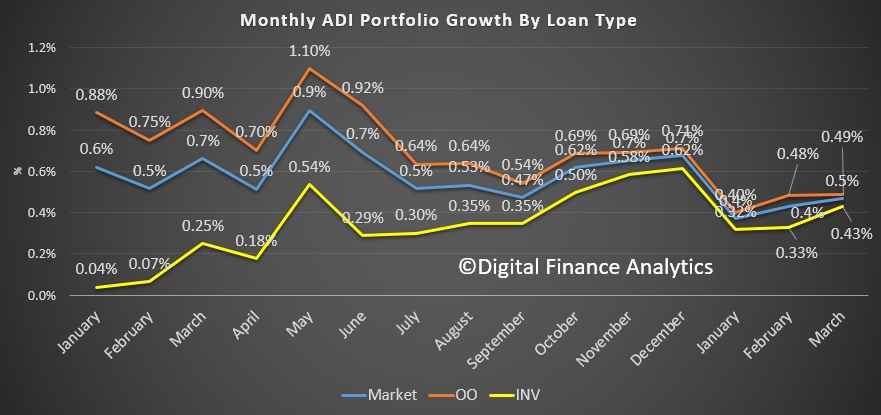

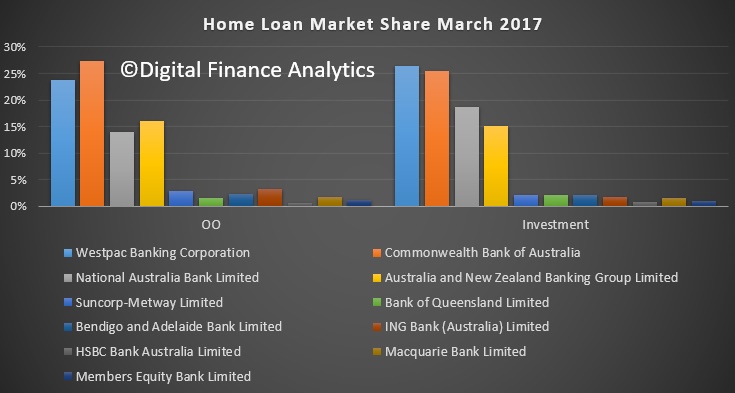

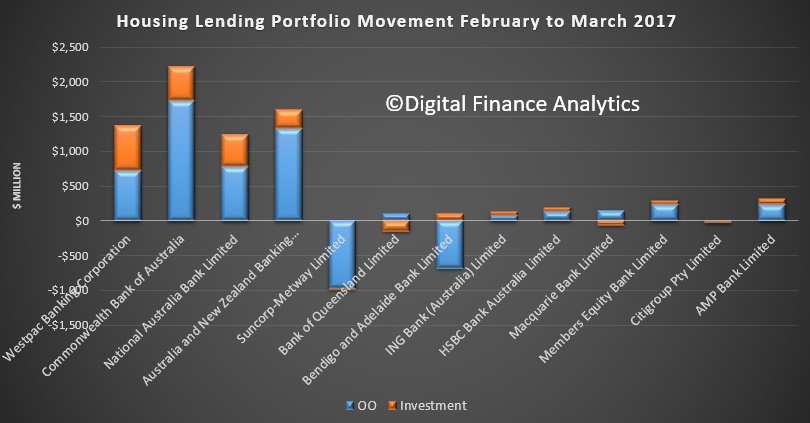

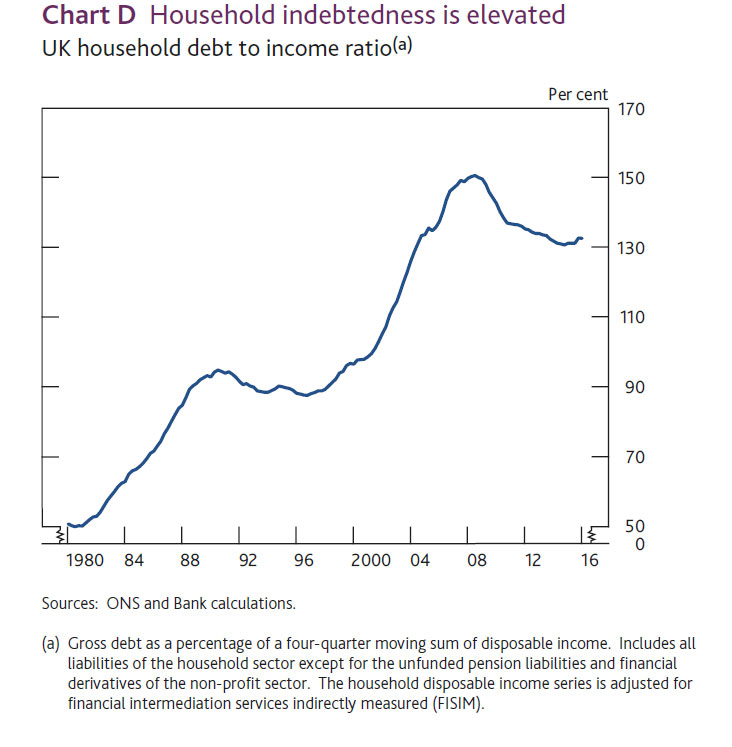

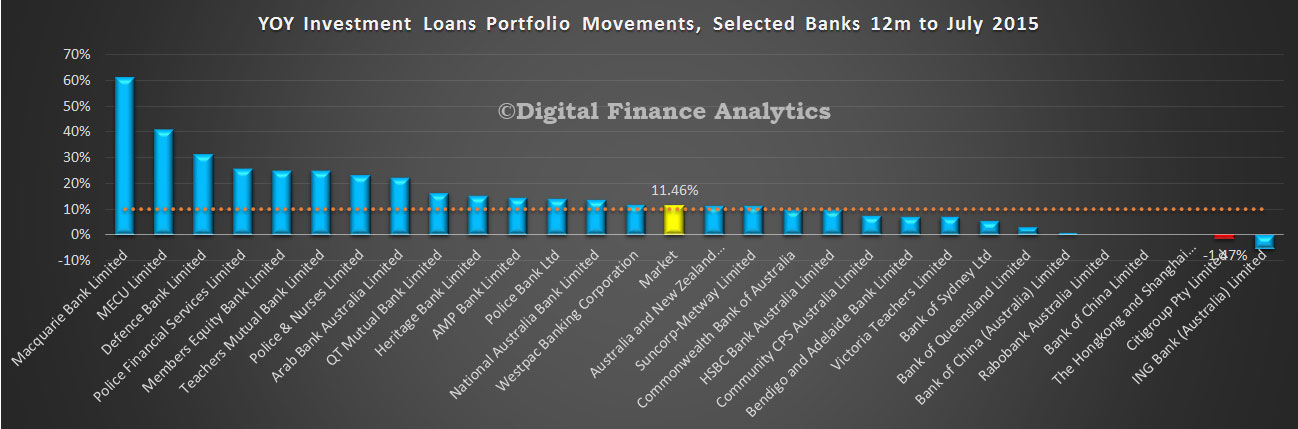

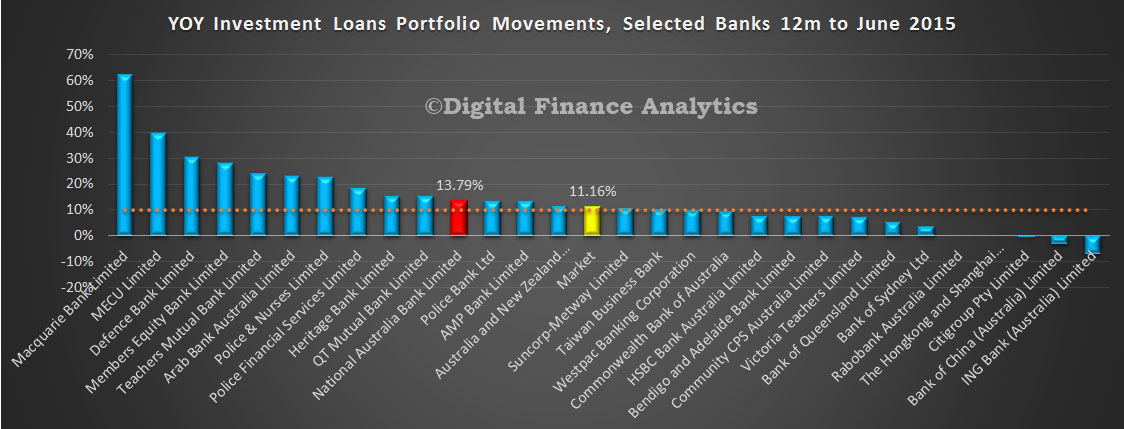

We have lifted our supervisory intensity in a number of ways – collecting more data from lenders, putting the matter on the agenda of Boards, establishing stronger lending standards that will serve to mitigate some of the risks from the current environment, and seeking in particular to moderate the rapid growth in lending to investors. These efforts are often tagged ‘macroprudential’, but in an environment of historically low interest rates, high household debt, relatively subdued wage growth, and strong competitive pressures, we see our role – in simple terms, seeking to make sure lenders continue to make sound loans to borrowers who can afford to pay them back – as really pretty basic bank supervision.

And just to be clear about it, we are not predicting whether house prices will go up or down or sideways (as the Governor of the Reserve Bank said last night, they are doing all these things in different parts of the country), but simply seeking to make sure that bank balance sheets are well equipped to handle whatever scenarios eventuate.

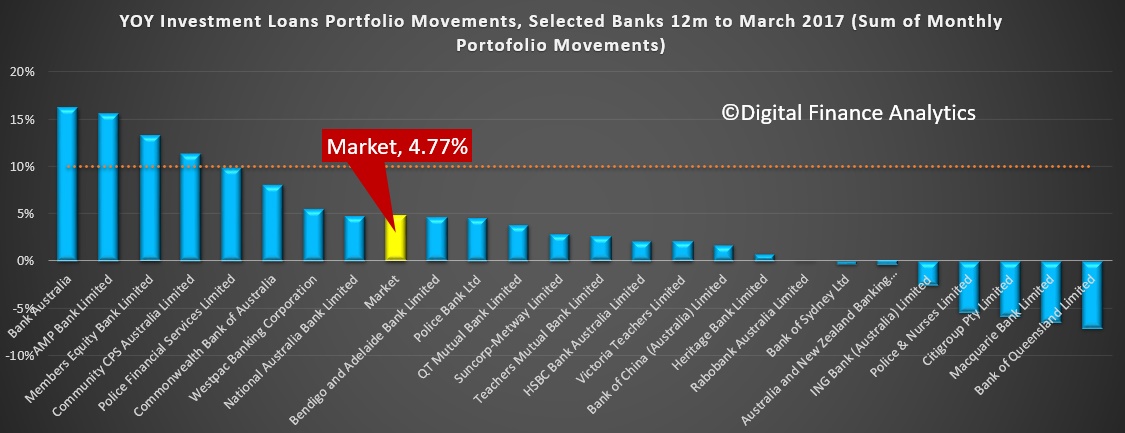

As things stand today, our recent efforts have generated a moderation in investor lending, which was accelerating at double digit rates of growth but has now come back into single figures. We can also be more confident in the quality of mortgage lending decisions today relative to a few years ago.

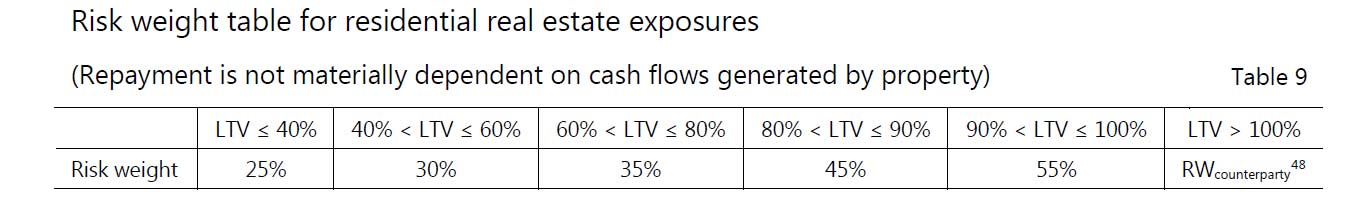

We are not complacent, however, as recent months have seen a pick-up in the rate of new lending to investors. That pick-up in itself is not necessarily surprising – with so much construction activity being completed and the resulting settlement of purchases, some pick-up in the rate of growth might be expected. But, at least for the time being, the benchmarks that we communicated – including the 10 per cent benchmark for annual growth in investor lending – remain in place and lenders that choose to operate beyond these benchmarks are under no illusions that supervisory intervention, probably in the form of higher capital requirements, is a possible consequence. If that is encouraging them to direct their competitive instincts elsewhere, then that’s probably a good thing for the system as a whole.

I have focussed very much on banking in my remarks thus far, so before my time is up I thought I would also comment on an issue that is relevant right across the financial system: the need to continue investment in existing technology platforms while at the same time putting money into new technology which may well replace it. This conundrum exists for all firms we supervise, and the issue is going to rise in importance as time goes by.

The Australian financial sector is, on the whole, pretty quick to adapt new technology as it emerges. And we have some important new infrastructure currently being built, like the New Payments Platform that will facilitate payments 24/7. But we also face the challenge that, like many parts of the world, large parts of financial firms’ core operating platforms are still based on technology that is increasingly dated, and not as integrated as it needs to be.

Particularly with the rise of fintech and potential disruptors, the temptation in the current environment is to devote a larger proportion of any investment budget to shiny new toys at the front end that excite the customer, and perhaps defer a bit of maintenance on the back office functions that make sure the customers’ transactions actually get processed and recorded correctly. As a supervisor, we are very keen to see investment in new technology by financial firms, because we think it offers considerable benefit to the soundness, efficiency and competitiveness of the financial system. The important thing for us is to make sure investment budgets are expanding to accommodate that, and it is not simply funded by a diversion of resources from other essential tasks.

I’ll conclude here and give the floor to my other panellists. I will, of course, be happy to take any questions you might have once they have had a chance to make their remarks.